- Double jeopardy

-

Criminal procedure Criminal trials and convictions Rights of the accused Fair trial · Speedy trial

Jury trial · Counsel

Presumption of innocence

Exclusionary rule1

Self-incrimination

Double jeopardy2Verdict Conviction · Acquittal

Not proven3

Directed verdictSentencing Mandatory · Suspended

Custodial

Dangerous offender4, 5

Capital punishment

Execution warrant

Cruel and unusual punishment

Life · IndefinitePost-sentencing Parole · Probation

Tariff6 · Life licence6

Miscarriage of justice

Exoneration · Pardon

Sexually violent predator legislation1Related areas of law Criminal defenses

Criminal law · Evidence

Civil procedurePortals Law · Criminal justice 1 US courts. 2 Not in English/Welsh courts. 3 Scottish courts. 4 English/Welsh courts. 5 Canadian courts. 6 UK courts. Double jeopardy is a procedural defense that forbids a defendant from being tried again on the same, or similar charges following a legitimate acquittal or conviction. At common law a defendant may enter a peremptory plea of autrefois acquit or autrefois convict (autrefois means "previously" in French), meaning the defendant has been acquitted or convicted of the same offense.[1]

If this issue is raised, evidence will be placed before the court, which will normally rule as a preliminary matter whether the plea is substantiated, and if it so finds, the projected trial will be prevented from proceeding. In many countries the guarantee against being "twice put in jeopardy" is a constitutional right; these include India, Mexico, and the United States. In other countries, the protection is afforded by statute law.[3]

Contents

Australia

In contrast to other common law nations, Australian double jeopardy law has been held to extend to the prevention of prosecution for perjury following a previous acquittal where a finding of perjury would controvert the previous acquittal. This was confirmed in the case of R v Carroll, where the police found new evidence convincingly disproving Carroll's sworn alibi two decades after he had been acquitted of murder charges in the death of Ipswich child Deidre Kennedy, and successfully prosecuted him for perjury. Public outcry following the overturning of his conviction (for perjury) by the High Court has led to widespread calls for reform of the law along the lines of the UK legislation.

In December 2006, New South Wales Premier Morris Iemma introduced legislation to scrap substantial parts of the double jeopardy law in that state. Retrials of serious cases with a minimum sentence of 20 years or more are now possible, even when the original trial preceded the 2006 reform.[4] On 17 October 2006, the NSW Parliament passed legislation abolishing the rule against double jeopardy in cases where:

- someone acquitted of a "life sentence offence" (murder, violent gang rapes, large commercial supply or production of illegal drugs) where there is "fresh and compelling" evidence of guilt;

- someone acquitted of a "15 years or more sentence offence" where the acquittal was tainted (by perjury, bribery or perversion of the course of justice); and,

- someone acquitted in a judge-only trial or where a judge directed the jury to acquit.[5] This largely grew out of the case of Raymond John Carroll.[6]

On 30 July 2008, the South Australia government introduced legislation to scrap parts of its double jeopardy law. Retrials for serious offences, where there is "fresh and compelling" evidence, or if the acquittal was tainted were proposed.[7]

On 8 September 2011, amendments were introduced in the Western Australia parliament to reform the state's double jeopardy laws. The proposed amendments would allow retrial if "new and compelling" evidence was found. It would apply to serious offences where the penalty was life imprisonment or imprisonment for 14 years or more. Acquittal because of tainting (threatening of witnesses, jury tampering, or perjury) would also allow retrial.[8] [9]

On 19 August 2008, amendments were introduced in Tasmania to allow retrial in serious cases, if there is "fresh and compelling" evidence.[10]

In June 2011 Victoria was considering changing their double jeopardy laws.[11]

On 18 October 2007, Queensland modified its double jeopardy laws to allow a retrial where fresh and compelling evidence becomes available after an acquittal for murder or a 'tainted acquittal' for a crime carrying a 25-year or more sentence. A 'tainted acquittal' requires a conviction for an administration of justice offence, such as perjury, that led to the original acquittal. Unlike reforms in the United Kingdom and New South Wales, this law does not have a retrospective effect, which is unpopular with some[who?] advocates of the reform.

According to the University of New South Wales, the federal government is pushing hard for ‘reform’ of double jeopardy throughout Australia.[5]

Canada

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms includes provisions such as section 11(h) prohibiting double jeopardy. But often this prohibition applies only after the trial is finally concluded. Canadian law allows the prosecution to appeal from an acquittal. If the acquittal is thrown out, the new trial is not considered to be double jeopardy because the first trial and its judgment would have been annulled. In rare circumstances, a court of appeal might also substitute a conviction for an acquittal. This is not considered to be double jeopardy either - in this case the appeal and subsequent conviction are deemed to be a continuation of the original trial.

For an appeal from an acquittal to be successful, the Supreme Court of Canada requires that the Crown show an error in law was made during the trial and that the error contributed to the verdict. It has been suggested that this test is unfairly beneficial to the prosecution. For instance, Martin L Friedland, in his book My Life in Crime and Other Academic Adventures, contends that the rule should be changed so that a retrial is granted only when the error is shown to be responsible for the verdict, not just one of many factors.

A notable example of this is the case of David Ahenakew or Colby Campbell, who were tried a second time after being acquitted.

European Convention on Human Rights

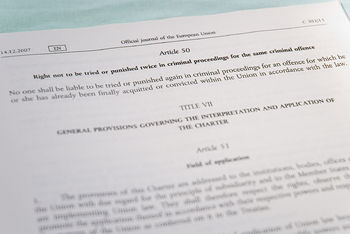

Article 50 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union protects against double jeopardy.

Article 50 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union protects against double jeopardy.

All members of the Council of Europe (which includes nearly all European countries, and every member of the European Union) have signed the European Convention on Human Rights, which protects against double jeopardy. The optional Seventh Protocol to the Convention, Article Four, says:

No one shall be liable to be tried or punished again in criminal proceedings under the jurisdiction of the same State for an offence for which he or she has already been finally acquitted or convicted in accordance with the law and penal procedure of that State.

Member states may, however, implement legislation which allows reopening of a case in the event that new evidence is found or if there was a fundamental defect in the previous proceedings.

The provisions of the preceding paragraph shall not prevent the reopening of the case in accordance with the law and penal procedure of the State concerned, if there is evidence of new or newly discovered facts, or if there has been a fundamental defect in the previous proceedings, which could affect the outcome of the case.

This optional protocol has been ratified by all EU states except five (namely Belgium, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, and United Kingdom).[12] In those member states, national rules governing double jeopardy may or may not comply with the provision cited above.

In many European countries the prosecution may appeal an acquittal to a higher court (similar to the provisions of Canadian law) – this is not counted as double jeopardy but as a continuation of the same trial. This is allowed by the European Convention on Human Rights – note the word finally in the above quotation.

France

Once all appeals have been exhausted on a case, the judgment is final and the action of the prosecution is closed (code of penal procedure, art. 6), except if the final ruling was forged.[13] Prosecution for an already judged crime is impossible even though new incriminating evidence has been found. However, a person who has been convicted may request another trial on grounds of new exculpating evidence through a procedure known as révision.[14]

Germany

In Germany, the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany does not provide comprehensive protection against double jeopardy.

Nobody shall be punished multiple times for the same crime on the base of general criminal law.

— Art. 103 (3) GG[15]

Based on pre-constitutional case law, the clause is constructed to also protect against double jeopardy in the case of an acquittal. However, both the prosecution210 and defense may appeal against the verdict on questions of law and fact in less serious offences; in more serious offences, appeals are restricted to questions of law.[16]

The rule applies to the whole "historical event, which is usually considered a single historical course of actions the separation of which would seem unnatural". This is true even if new facts occur that indicate other and/or much serious crimes.

The Penal Procedural Code (Strafprozessordnung - StPO) provides some exceptions to the double jeopardy rule:

A retrial not in favour of the defendant is permissible after a final judgment,

- if a document that was considered authentic during the trial was actually not authentic or forged,

- if a witness or authorised expert wilfully or negligently made a wrong deposition or willfully gave a wrong simple testimony,

- if a professional or lay judge, who made the decision, had committed a crime by violating his or her duties as a judge in the case

- if an acquitted defendant makes a credible confession in court or out of court.

— § 362 StPO

In the case of an order of summary punishment (Strafbefehl), which can be issued by the court without a trial for lesser misdemeanours (German: Vergehen), there is a further exception:

A retrial not in favour of the defendant is also permissible if the defendant has been convicted in a final order of summary punishment and new facts or evidence have been brought forward, which establish grounds for a conviction of a felony by themselves or in combination with earlier evidence.

— § 373a StPO

A felony (German: Verbrechen) is defined as a crime which has a usual minimum sanction of one year of imprisonment.

India

A partial protection against double jeopardy is a Fundamental Right guaranteed under Article 20 (2) of the Constitution of India. This states that ""No person shall be prosecuted and punished for the same offence more than once".[17] This provision enshrines the concept of autrefois convict, that no convicted of an offence can be tried or punished a second time. However it does not extend to autrefois acquit, and so if a person is acquitted of a crime he can be retried. In India, protection against autrefois acquit is a statuatory right, not a fundamental right. Such protection is provided by provisions of the Code of Criminal Procedure rather than by the Constitution.[18]

International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights

The 72 signatories and 166 parties to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights recognise this rule, under Article 14 (7): No one shall be liable to be tried or punished again for an offence for which he has already been finally convicted or acquitted in accordance with the law and penal procedure of each country.

Japan

The Constitution of Japan states in Article 39 that

- No person shall be held criminally liable for an act which was lawful at the time it was committed, or of which he has been acquitted, nor shall he be placed in double jeopardy.

However, in practice, if someone is acquitted in a lower District Court, then the prosecutor can appeal to the High Court, and then to the Supreme Court. Only the acquittal in the Supreme Court is the final acquittal which prevents any further retrial. This process sometimes takes decades.

The above is not considered a violation of the constitution, because of Supreme Court precedent, this process is all considered part of a single jeopardy.[19]

Netherlands

In the Netherlands, the state prosecution can appeal against a not-guilty verdict at the bench. New evidence can be brought to bear during a retrial at a district court. Thus one can be tried twice for the same alleged crime. If one is convicted at the district court, the defence can make an appeal on procedural grounds to the supreme court. The supreme court might admit this complaint, and the case will be reopened yet again, at another district court. Again, new evidence might be introduced by the prosecution.

According to Dutch legal experts Crombag, Wagenaar, van Koppen, the Dutch system contravenes the provisions of the European Human Rights convention, in the imbalance between the power of the prosecution service and the defence.

Pakistan

Article 13 of the Constitution of Pakistan protects a person from being punished or prosecuted more than once for the same offence.

Serbia

This principle is incorporated in to the Constitution of the Republic of Serbia and further elaborated in its Criminal Procedure Act.[20]

South Africa

The Bill of Rights in the Constitution of South Africa forbids a retrial when there has already been an acquittal or a conviction.

Every accused person has a right to a fair trial, which includes the right ... not to be tried for an offence in respect of an act or omission for which that person has previously been either acquitted or convicted ...

— Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996, s. 35(3)(m)

United Kingdom

England and Wales

Double jeopardy has been permitted in England and Wales since the Criminal Justice Act 2003.

Pre-2003

The doctrines of autrefois acquit and autrefois convict persisted as part of the common law from the time of the Norman conquest of England; they were regarded as essential elements of protection of the liberty of the subject and respect for due process of law in that there should be finality of proceedings.[1] There were only three exceptions, all relatively recent, to the rules:

- The prosecution has a right of appeal against acquittal in summary cases if the decision appears to be wrong in law or in excess of jurisdiction.[21]

- A retrial is permissible if the interests of justice so require, following appeal against conviction by a defendant.[22]

- A "tainted acquittal", where there has been an offence of interference with, or intimidation of, a juror or witness, can be challenged in the High Court.[23]

In Connelly v DPP ([1964] AC 1254), the Law Lords ruled that a defendant could not be tried for any offence arising out of substantially the same set of facts relied upon in a previous charge of which he had been acquitted, unless there are "special circumstances" proven by the prosecution. There is little case law on the meaning of "special circumstances", but it has been suggested that the emergence of new evidence would suffice.[24]

A defendant who had been convicted of an offence could be given a second trial for an aggravated form of that offence if the facts constituting the aggravation were discovered after the first conviction.[25] By contrast, a person who had been acquitted of a lesser offence could not be tried for an aggravated form even if new evidence became available.[26]

Post-2003

Following the murder of Stephen Lawrence, the Macpherson Report suggested that double jeopardy should be abrogated where "fresh and viable" new evidence came to light, and the Law Commission recommended in 2001 that it should be possible to subject an acquitted murder suspect to a second trial. The Parliament of the United Kingdom implemented these recommendations by passing the Criminal Justice Act 2003,[27] introduced by then Home Secretary David Blunkett. The double jeopardy provisions of the Act came into force in April 2005,[28] but are applicable to crimes committed before then.

Under the 2003 Act, retrials are now allowed if there is "new" and "compelling" evidence for certain serious crimes, including murder, manslaughter, kidnapping, rape, armed robbery, and serious drug crimes. All such retrials must be approved by the Director of Public Prosecutions, and the Court of Appeal must agree to quash the original acquittal.[29]

On 11 September 2006, William Dunlop became the first person to be convicted of murder after previously being acquitted. Twice he was tried for the murder of Julie Hogg in Billingham in 1989, but two juries failed to reach a verdict and he was formally acquitted in 1991. Some years later, he confessed to the crime, and was convicted of perjury. The case was re-investigated in early 2005, when the new law came into effect, and his case was referred to the Court of Appeal in November 2005 for permission for a new trial, which was granted.[30][31][32] Dunlop pleaded guilty to murdering Julie Hogg and raping her dead body repeatedly, and was sentenced to life imprisonment, with a recommendation he serve no less than 17 years.[33]

On 13 December 2010, Mark Weston became the first person to be convicted of murder after previously being found not guilty of the same offence, that of the murder of Vikki Thompson at Ascott-under-Wychwood on 12 August 1995. Weston's first trial was in 1996, when the jury found him not guilty. Following the discovery of compelling new evidence in 2009 – Thompson's blood on Weston's boots – Weston was arrested in 2009 and tried for a second time in December 2010, when he was found guilty of Thompson's murder, and sentenced to life imprisonment to serve a minimum of 13 years.[34]

Scotland

The double jeopardy rule still applies in Scotland, although the Scottish government on October 7, 2010 introduced legislation to remove the bar to retrials in cases of murder, rape, serious sexual crimes and culpable homicide. In March 2010 the Scottish Law Commission recommended revision of the ancient constitutional principle in cases of murder and rape, but the proposed legislation extends the repeal also to cases involving culpable homicide and serious sexual crimes (such as sexual crimes against children).[35] The legislation provides for retroactive application so as to permit the retrial of Angus Sinclair for the World's End murders of Helen Scott and Christine Eadie.[36]

Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland the Criminal Justice Act of 2003, effective April 18, 2005,[37] makes certain "qualifying offence" (including murder, rape, kidnapping, specified sexual acts with young children, specified drug offences, defined acts of terrorism, as well as in certain cases attempts or conspiracies to commit the foregoing[38]) subject to retrial after acquittal (including acquittals obtained before passage of the Act) if there is a finding by the Court of Appeals that there is "new and compelling evidence."[39]

United States

The double jeopardy rule arises from the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the relevant clause of which reads: "[no person shall] be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb"[citation needed].

This clause is intended to limit abuse by the government in repeated prosecution for the same offense as a means of harassment or oppression. It is also in harmony with the common law concept of res judicata which prevents courts from relitigating issues which have already been the subject of a final judgment[citation needed].

More specifically, as stated in Ashe v. Swenson, 397 U.S. 436 (1970): "...when an issue of ultimate fact has once been determined by a valid and final judgment, that issue cannot again be litigated between the same parties in any future lawsuit." Res judicata is a term of general application. Underneath that conceptual umbrella is the concept of collateral estoppel. As applied to double jeopardy, the court will use collateral estoppel as its basis for forming an opinion[citation needed].

There are three essential protections included in the double jeopardy principle, which are:

- being tried for the same crime after an acquittal

- retrial after a conviction, unless the conviction has been reversed, vacated or otherwise nullified

- being punished multiple times for the same offense

This rule is occasionally referred to as a legal technicality because it allows defendants a defense that does not address whether the crime was actually committed. For example, were police to uncover new evidence conclusively proving the guilt of someone previously acquitted, there is little they can do because the defendant may not be tried again—at least not on the same or a substantially similar charge.[40]

Although the Fifth Amendment initially applied only to the federal government, the U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that the double jeopardy clause applies to the states as well through incorporation by the Fourteenth Amendment (Benton v. Maryland).

Jeopardy attaches in a jury trial once the jury and alternates are impaneled and sworn in. In a non-jury trial jeopardy attaches once the first evidence is put on which occurs when the first witness is sworn.[citation needed]

Exceptions

Non-final judgments

As double jeopardy applies only to charges that were the subject of an earlier final judgment, there are many situations in which it does not apply despite the appearance of a retrial. For example, a second trial held after a mistrial does not violate the double jeopardy clause because a mistrial ends a trial prematurely without a judgment of guilty or not as decided by the U.S. Supreme Court in United States v. Josef Perez. Cases dismissed because of insufficient evidence may constitute a final judgment for these purposes though many state and federal laws allow for substantially limited prosecutorial appeals from these orders. Also, a retrial after a conviction has been set aside following the grant of a motion for new trial, has been reversed on appeal, or has been vacated in a collateral proceeding (such as habeas corpus), does not violate double jeopardy because the judgment in the first trial has been invalidated. In all of these cases, however, the previous trials do not entirely vanish. Testimony from them may be used in later retrials such as to impeach contradictory testimony given at any subsequent proceeding.

Fraudulent trials

There are two exceptions to the general rule that the prosecution cannot appeal an acquittal:

- If the earlier trial is proven to be a fraud or scam, double jeopardy will not prohibit a new trial. In the case of Harry Aleman[41] an appeals court ruled that a man who bribed his trial judge and was acquitted of murder was allowed to be tried again because his bribe prevented his first trial from actually putting him in jeopardy.

- Prosecutors may appeal when a trial judge sets aside a jury verdict for conviction with a judgment notwithstanding verdict for the defendant. A successful appeal by the prosecution would simply reinstate the jury verdict and so would not place the defendant at risk of another trial.

The U.S. Supreme Court has also upheld laws allowing the government to appeal criminal sentences in limited circumstances (such as that of ). The Court ruled that sentences were not accorded the same constitutional finality as jury verdicts under the double jeopardy clause, and giving this right of appeal also did not put the defendant at risk of a succession of prosecutions.

Double jeopardy is also not implicated for separate offenses or in separate jurisdictions arising from the same act. For example, in United States v. Felix 503 U.S. 378 (1992), the U.S. Supreme Court ruled: "a[n]...offense and a conspiracy to commit that offense are not the same offense for double jeopardy purposes."[42][43]

Separate sovereigns

The "separate sovereigns" exception to double jeopardy arises from the dual nature of the American Federal-State system, one in which states are sovereigns with plenary power that have relinquished a number of enumerated powers to the Federal government. Double jeopardy attaches only to prosecutions for the same criminal act by the same sovereign, but as separate sovereigns, both the federal and state governments can bring separate prosecutions for the same act.

As an example, a state might try a defendant for murder, after which the Federal government might try the same defendant for a Federal crime (perhaps a civil rights violation or a kidnapping) connected to the same act. For example, the officers of the Los Angeles Police Department who were charged with assaulting Rodney King in 1991 were acquitted by a jury of the Superior Court, but some were later convicted and sentenced in Federal court for violating King's civil rights. Similar legal processes were used for prosecuting racially-motivated crimes in the Southern United States in the 1960s during the time of the Civil Rights movement, when those crimes had not been actively prosecuted, or had resulted in acquittals by juries that were thought to be racist or overly-sympathetic with the accused in local courts.

Federal jurisdiction may apply because the defendant is a member of the armed forces or the victim(s) are armed forces members or dependents. U.S. Army Master Sergeant Timothy B. Hennis was acquitted in state court in North Carolina for the murders in 1985 of Kathryn Eastburn (age 31) and her daughters Kara, age five, and Erin, age three, who were stabbed to death in their home near Fort Bragg, North Carolina.[44] Two decades later, Hennis was recalled to active duty, court-martialed by the Army for the crime, and convicted.[45]

Furthermore, the "separate sovereigns" rule allows two states to prosecute for the same criminal act. For example, if a man stood in New York and shot and killed a man standing over the border in Connecticut, both New York and Connecticut could charge the shooter with murder.[46]

Only the states and tribal jurisdictions[47] are recognized as possessing a separate sovereignty, whereas territories, commonwealths (for example, Puerto Rico), the military and naval forces, and the capital city of Washington, D.C., are exclusively under Federal sovereignty. Acquittal in the court system of any of these entities would therefore preclude a re-trial (or a court-martial) in any court system under Federal jurisdiction.

Concerning different legal standards

Double jeopardy also does not apply if the later charge is civil rather than criminal in nature, which involves a different legal standard (crimes must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt, whereas civil wrongs need only be proven by preponderance of evidence). Acquittal in a criminal case does not prevent the defendant from being the defendant in a civil suit relating to the same incident (though res judicata operates within the civil court system). For example, O.J. Simpson was acquitted of a double homicide in a California criminal prosecution, but lost a civil wrongful death claim brought over the same victims.

If the defendant happened to be on parole from an earlier offense at the time, the act for which he or she was acquitted may also be the subject of a parole violation hearing, which is not considered to be a criminal trial. Since parolees are usually subject to restrictions not imposed on other citizens, evidence of actions that were not deemed to be criminal by the court may be re-considered by the parole board. This legal board could deem the same evidence to be proof of a parole violation. Most states' parole boards have looser rules of evidence than is found in the courts - for example, hearsay that had been disallowed in court might be considered by a parole board. Finally, like civil trials parole violation hearings are also subject to a lower standard of proof so it is possible for a parolee to be punished by the parole board for criminal actions that he or she was acquitted of in court.

In the American military or naval courts-martial are subject to the same law of double jeopardy, since the Uniform Code of Military Justice has incorporated all of the protections of the U.S. Constitution. The non-criminal proceeding non-judicial punishment (or NJP) is considered to be akin to a civil case and is subject to lower standards than a court-martial, which is the same as a civilian court of law. NJP proceedings are commonly used to correct or punish minor breaches of military discipline. However if a NJP proceeding fails to produce conclusive evidence, the commanding officer (or ranking official presiding over the NJP) is not allowed to prepare the same charge against the military member in question. In a court-martial, acquittal of the defendant means he is protected permanently from having those charges reinstated.

The most famous American court case invoking the claim of double jeopardy is probably the second murder trial in 1876 of Jack McCall, killer of Wild Bill Hickok. McCall was acquitted in his first trial, which Federal authorities later ruled to be illegal because it took place in an illegal town, Deadwood, then located in South Dakota Indian Territory. At the time Federal law prohibited all except for Native Americans from settling in the Indian Territory. McCall was retried in Federal Indian Territorial court, convicted, and hanged in 1877. He was the first person ever executed by Federal authorities in the Dakota Territory.

Double jeopardy also does not apply if the defendant was never tried from the start. Charges that were dropped or put on hold for any reason can always be reinstated in the future—if not barred by some statute of limitations.

See also

- Roman law: Ne bis in idem

- Sam Sheppard

- U.S. law: Fifth Amendment

Footnotes

- ^ a b Benét, Stephen Vincent (1864). A treatise on military law and the practice of courts-martial. p. 97. http://books.google.com/?id=Gq00AAAAIAAJ.

- ^ Criminal Code Act Compilation Act 1913 (see p. 47; p. 51 of the PDF), State Law Publisher of Western Australia.

- ^ e.g., in Western Australia protection against double jeopardy is provided by section 17 of the Criminal Code Act Compilation Act 1913.[2]

- ^ NSW seeks to scrap double jeopardy principle, The World Today.

- ^ a b NSW abolishes double jeopardy, University of NSW.

- ^ Double Jeopardy and the Carroll Case, University of NSW.

- ^ "Criminal Law Consolidation (Double Jeopardy) Amendment Act 2008". Criminal Law Consolidation (Double Jeopardy) Amendment Act 2008. http://www.legislation.sa.gov.au/LZ/V/A/2008/CRIMINAL%20LAW%20CONSOLIDATION%20(DOUBLE%20JEOPARDY)%20AMENDMENT%20ACT%202008_28/2008.28.UN.RTF. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ "Attorney General Christian Porter welcomes double jeopardy law reform". Attorney General Christian Porter welcomes double jeopardy law reform. http://www.perthnow.com.au/news/western-australia/attorney-general-christian-porter-welcomes-double-jeopardy-law-reform/story-e6frg13u-1226132121880. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ "WA the next state to axe double jeopardy". WA the next state to axe double jeopardy. http://news.smh.com.au/breaking-news-national/wa-the-next-state-to-axe-double-jeopardy-20110908-1jyu3.html. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ "Double Jeopardy Law Reform". Double Jeopardy Law Reform. Tasmanian Government Media Releases. http://www.media.tas.gov.au/print.php?id=24539. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ "Victoria's double jeopardy laws to be reworked". Victoria's double jeopardy laws to be reworked. http://www.heraldsun.com.au/news/more-news/victorias-double-jeopardy-laws-to-be-reworked/story-fn7x8me2-1226068708669. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ^ Protocol No. 7 to the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, Council of Europe.

- ^ Code of penal procedure, article 6

- ^ Code of penal procedure, articles 622-626

- ^ Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland (German), Lochner Abroad: Substantive Due Process and Equal Protection in the Federal Republic of Germany.

- ^ CONSULTATION PAPER ON PROSECUTION APPEALS IN CASES BROUGHT ON INDICTMENT, CHAPTER ONE: PROSECUTION APPEALS IN IRELAND AND ABROAD, D. PROSECUTION AVENUES OF APPEAL IN FOREIGN JURISDICTIONS, (g) Germany, Law Reform Commission of Ireland.

- ^ Article 20, Section 2 of the Constitution of India reads, "No person shall be prosecuted and punished for the same offence more than once."

- ^ Sharma; Sharma B.k. (2007). Introduction to the Constitution of India. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd.. pp. 94. ISBN 978-81-203-3246-1. http://books.google.com/books?id=srDytmFE3KMC.

- ^ http://blog.livedoor.jp/plltakano/archives/54254570.html

- ^ Article 6. of the Criminal Procedure Act - ZAKONIK O KRIVIČNOM POSTUPKU ("Sl. list SRJ", br. 70/2001 i 68/2002 i "Sl. glasnik RS", br. 58/2004, 85/2005, 115/2005, 85/2005 - dr. zakon, 49/2007, 20/2009 - dr. zakon i 72/2009)

- ^ Magistrates’ Courts Act 1980 ss.28, 111; Supreme Court Act 1981 s.28

- ^ Criminal Appeal Act 1968 s.7

- ^ Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996 s.54

- ^ Attorney-General for Gibraltar v Leoni, Court of Appeal, 1999 (unreported) see Law Com CP No 156, para 2.24

- ^ R v Thomas [1950] 1 KB 26

- ^ R v Beedie [1998] QB 356, Dingwall, 2000

- ^ Criminal Justice Act 2003 (c. 44).

- ^ Double jeopardy law ushered out, BBC News.

- ^ The CPS : Retrial of Serious Offences

- ^ Man faces double jeopardy retrial, BBC News.

- ^ Murder conviction is legal first, BBC News.

- ^ The law of 'double jeopardy', BBC News.

- ^ Double jeopardy man is given life, BBC News.

- ^ "'Double jeopardy' man guilty of Vikki Thompson murder". BBC News Oxford. 13 December 2010. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-oxfordshire-11982681. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- ^ "Double Jeopardy Reforms," Press Release of the Scottish Government, October 10, 2010.

- ^ "Double jeopardy law will be scrapped in Scotland," BBC News, August 14, 2010.

- ^ "Commencement of Provisions - Criminal Justice Act of 2003," Northern Ireland Office.

- ^ Schedule 5 Part 2 of the Criminal Justice Act of 2003.

- ^ "Retrial for serious offences," Part 10 of Criminal Justice Act of 2003.

- ^ Fong Foo v. United States, 369 U.S. 141 (1962)

- ^ Harry Aleman, Petitioner-appellant, v. the Honorable Judges of the Circuit Court of Cook County, criminal Division, Illinois, Honorable Michael P. Toomin,judge Presiding, Honorable Richard Devine, State's Attorney of Cook County, Illinois, Ernesto Velasco, Executive Director, Cook County Department of Corrections,respondents-appellees; United States Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit. - 138 F.3d 302; Argued Dec. 2, 1997; Decided March 6, 1998; justia.com

- ^ Donofrio, Anthony J. (1993). "The Double Jeopardy Clause of the Fifth Amendment: The Supreme Court's Cursory Treatment of Underlying Conduct in Successive Prosecutions". Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 83 (4): 773–803. doi:10.2307/1143871. JSTOR 1143871.

- ^ Shindala, C. (1992). "Where Conspiracy To Commit a Crime Is Based on Previously Prosecuted Overt Acts, No Double Jeopardy Violation Exists". Mississippi Law Journal 62 (1): 229–243. ISSN 0026-6280.

- ^ Innocent Victims (Onyx True Crime, Je 357) by Scott Whisnant

- ^ At 3rd Trial, Master Sgt. Timothy Hennis Guilty of 1985 Triple Murder - ABC News

- ^ United States v. Claiborne, 92 F.Supp.2d 503 (E.D.Va.); tandem state-federal prosecutions not prohibited under "sovereign rule"

- ^ United States v. Wheeler, 435 U. S. 313 (1978), supreme.justia.com.

External links

United States

Australia

In favor of current rule prohibiting retrial after acquittal

Opposing the rule that prohibits retrial after acquittal

Other countries

Categories:- Rights of the accused

- Legal terms

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.