- Negev

-

The Negev (also Negeb; Hebrew: נֶּגֶב, Tiberian vocalization: Néḡeḇ; Arabic: النقب al-Naqab) is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The Arabs, including the native Bedouin population of the region, refer to the desert as al-Naqab. The origin of the word Neghebh (or in Modern Hebrew Negev) is from the Hebrew root denoting 'dry'. In the Bible the word Neghebh is also used for the direction 'south'.

Contents

Geography

The Negev covers more than half of Israel, over some 13,000 km² (4,700 sq mi) or at least 55% of the country's land area. It forms an inverted triangle shape whose western side is contiguous with the desert of the Sinai Peninsula, and whose eastern border is the Arabah valley. The Negev has a number of interesting cultural and geological features. Among the latter are three enormous, craterlike makhteshim (box canyons), which are unique to the region; Makhtesh Ramon, Makhtesh Gadol, and Makhtesh Katan.

The Negev is a rocky desert. It is a melange of brown, rocky, dusty mountains interrupted by wadis (dry riverbeds that bloom briefly after rain) and deep craters. It can be split into five different ecological regions: northern, western, and central Negev, the high plateau and the Arabah Valley. The northern Negev, or Mediterranean zone, receives 300 mm of rain annually and has fairly fertile soils. The western Negev receives 250 mm of rain per year, with light and partially sandy soils. Sand dunes can reach heights of up to 30 metres here. Home to the city of Beersheba, the central Negev has an annual precipitation of 200 mm and is characterized by impervious soil, known as loess, allowing minimum penetration of water with greater soil erosion and water runoff. The high plateau area of Ramat HaNegev (Hebrew: רמת הנגב, The Negev Heights) stands between 370 metres and 520 metres above sea level with extreme temperatures in summer and winter. The area gets 100 mm of rain per year, with inferior and partially salty soils. The Arabah Valley along the Jordanian border stretches 180 km from Eilat in the south to the tip of the Dead Sea in the north. The Arabah Valley is very arid with barely 50 mm of rain annually. It has inferior soils in which little can grow without irrigation and special soil additives.

Climate

The whole Negev region is incredibly arid (Eilat receives on average only 31 mm of rainfall a year), receiving very little rain due to its location to the east of the Sahara (as opposed to the Mediterranean which lies to the west of Israel), and extreme temperatures due to its location 31 degrees north.

The average rainfall total from June through October is zero.[1]

Climate data for Beersheba Month Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Year Record high °C (°F) 28.4

(83.1)31

(88)35.4

(95.7)40.9

(105.6)42.2

(108.0)46

(115)41.5

(106.7)40.5

(104.9)41.2

(106.2)39.6

(103.3)34

(93)31.4

(88.5)46

(115)Average high °C (°F) 16.7

(62.1)17.5

(63.5)20.1

(68.2)25.8

(78.4)29

(84)31.3

(88.3)32.7

(90.9)32.8

(91.0)31.3

(88.3)28.5

(83.3)23.5

(74.3)18.8

(65.8)25.7 Average low °C (°F) 7.5

(45.5)7.6

(45.7)9.3

(48.7)12.7

(54.9)15.4

(59.7)18.4

(65.1)20.5

(68.9)20.9

(69.6)19.5

(67.1)16.7

(62.1)12.6

(54.7)8.9

(48.0)14.2 Record low °C (°F) −5

(23)−0.5

(31.1)2.4

(36.3)4

(39)8

(46)13.6

(56.5)15.8

(60.4)15.6

(60.1)13

(55)10.2

(50.4)3.4

(38.1)3

(37)−5

(23)Precipitation mm (inches) 49.6

(1.953)40.4

(1.591)30.7

(1.209)12.9

(0.508)2.7

(0.106)0

(0)0

(0)0

(0)0.4

(0.016)5.8

(0.228)19.7

(0.776)41.9

(1.65)204.1

(8.035)Avg. precipitation days 9.2 8 6.4 2.6 0.8 0 0 0 0.1 1.8 4.6 7.5 41 Source: Israel Meteorological Service[2][3] History

Nomads

Nomadic life in the Negev dates back at least 4,000 years [4] and perhaps as much as 7,000 years.[5] The first urbanized settlements were established by a combination of Canaanite, Amalekite, and Edomite groups circa 2000 BC.[4] Pharaonic Egypt is credited with introducing copper mining and smelting in both the Negev and the Sinai between 1400 and 1300 BC.[4][6]

Biblical

According to the Book of Genesis chapter 20, Abraham lived for a while in the Negev near Kadesh after being banished from Egypt. Later the northern Negev was inhabited by the Tribe of Judah and the southern Negev by the Tribe of Shimon. The Negev was later part of the Kingdom of Solomon and then part of the Kingdom of Judah.

In the 9th century BC, development and expansion of mining in both the Negev and Edom (modern Jordan) coincided with the rise of the Assyrian Empire.[4] Beersheba was the region's capital and a center for trade in the 8th century BC.[4] Small settlements of Israelites in the areas around the capital existed between 1020 and 928 BC.[4]

Nabateans

The 4th century BC arrival of the Nabateans resulted in the development of irrigation systems that supported at least five new urban centers: Avdat, Mamshit, Shivta, Haluza (Elusa), and Nitzana.[4] The Nabateans controlled the trade and spice route between their capital Petra and the Gazan seaports. Nabatean currency and the remains of red and orange potsherds, identified as a trademark of their civilization, have been found along the route, remnants of which are also still visible.[4]

Nabatean control of the Negev ended when the Roman empire annexed their lands in 106 AD.[4] The population, largely made up of Arabian nomads and Nabateans, remained largely tribal and independent of Roman rule, with an animist belief system.[4]

Byzantines and Romans

Byzantine rule in the 4th century AD introduced Christianity to the population.[4] Agricultural-based cities were established and the population grew exponentially.[4]

The Bedouin: population and history 1000 A.D to 1948

(See section on Changing Ways of Life)

Main article: Negev BedouinsNomadic tribes ruled the Negev largely independently and with a relative lack of interference for the next thousand years.[4] What is known of this time is largely derived from oral histories and folk tales of tribes from the Wadi Musa and Petra areas in present-day Jordan.[4]

The Bedouins of the Negev historically survived chiefly on sheep and goat husbandry. Scarcity of water and of permanent pastoral land required them to move constantly. The Bedouin in years past established few permanent settlements, although some were built, leaving behind remnants of stone houses called 'baika.' [5] In 1900 the Ottoman Empire established an administrative center for southern Palestine at Beersheba including schools and a railway station.[4] The authority of the tribal chiefs over the region was recognized by the Ottomans.[4] A railroad connected it to the port of Rafah. By 1922 its population was 2,356, including 98 Jews and 235 Christians.[7] In contrast in 1914 the Turkish authorities estimated the nomadic population at 55,000.[8]

Prior to 1948 Censuses mentioned five major tribes in the Negev: the Tayaha, Tarabn, Azazma, Jabarat and Hanajra.

The tribal culture and way of life has changed dramatically recently, and today hardly any Bedouin citizens of Israel are nomadic.[9]

The Bedouins in Israel 1948-present

The Bedouins of the Negev were under military administration until 1967. The government of Israel concentrated these Bedouin tribes into the Siyag triangle of Beersheba, Arad and Dimona [10]

During 1949-1953 Israel expelled almost 17,000 Negev bedouins from the Negev, particularly from the al Auja triangle.[11]

In 1950, the Black Goat Law was installed to prevent land erosion, prohibiting the grazing of goats outside one's recognized land holdings[citation needed]. Since few Bedouin territorial claims were recognized, most grazing was thereby rendered illegal. The reason their territorial claims are not recognized was that both Ottoman and British land registration processes failed to reach into the Negev region; most Bedouin did not register their lands as to avoid being taxed. Those whose land claims were recognized found it almost impossible to keep their goats within the periphery of their land, and in the 1970s and 1980s, only a few Bedouin were able to continue to graze their goats. Instead of migrating with their goats in search of pasture, the majority of the Bedouin migrated in search of wage labor.[10]

In 1979, Agriculture Minister Ariel Sharon declared a 1,500 square kilometer area in the Negev a protected nature reserve, rendering a major portion of the Negev almost entirely out of bounds for Bedouin herders. In conjunction with this, he established the 'Green Patrol,'[12] the ‘environmental paramilitary unit’ with the mission of fighting Bedouin ‘infiltration’ into national Israeli land by preventing Bedouin from creating facts on the land and grazing their animals. During Sharon’s tenure as Minister of Agriculture (1977–1981), the Green Patrol removed 900 Bedouin encampments and cut goat herds by about a 1/3. [13]

Today the black goat is nearly extinct, and Bedouin in Israel do not have enough access to black goat hair to weave tents. Denied access to their former sources of sustenance, severed from the possibility of access to water, electricity, roads, education, and health care in the unrecognized villages, and trusting in government promises that they would receive services if they moved, in the 1970s and 1980s, tens of thousands of Bedouin resettled to 7 legal towns constructed by the government. (Falah, Ghazi. “The Spatial Pattern of Bedouin Sedentarization in Israel,” GeoJournal, 1985 Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 361–368.) However, the towns lacked any business districts and the urban townships have long been rife with the social breakdown resulting from near-total joblessness, crime and drugs.[13]

Today, at least 75,000 citizens live in 40 unrecognized villages.

Contemporary Negev

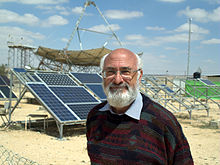

Campus of the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research, which is the epicenter of Israeli solar research.

Campus of the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research, which is the epicenter of Israeli solar research.

The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. 185,000), in the north. At its southern end is the Gulf of Aqaba=Gulf of Eilat and the resort city of Eilat. It contains several development towns, including Dimona, Arad, Mitzpe Ramon, as well as a number of small Bedouin cities, including Rahat and Tel as-Sabi. There are also several kibbutzim, including Revivim and Sde Boker; the latter became the home of Israel's first Prime Minister, David Ben-Gurion, after his retirement from politics.

The desert is home to the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, whose faculties include the Jacob Blaustein Institutes for Desert Research and the Albert Katz International School for Desert Studies, both located on the Midreshet Ben-Gurion campus adjacent to Sde Boker.

Today, the Negev has an enormous Israeli military presence and is home to many of the Israel Defense Forces major bases. As of 2010 the Negev was home to some 630,000 people (or 8.2% of Israel's population), even though it comprises over 55% of the country's landmass. 470,000 Negev residents or 75% of the population of the Negev are Jews while 160,000 or 25% of them are Negev Bedouin.[14] Of the Bedouin population, half live in unrecognized villages, and half live in towns built for them by the government between the 1960 and 1980s; the largest of these is Rahat.

Contemporary environmental issues

85% of the Negev is used by the Israel Defense Forces for training purposes.[15] In the remaining portion of the Negev available for civilian purposes, a large number of citizens live together in close proximity to a range of types of hazardous infrastructure, which includes a nuclear reactor, 22 agro and petrochemical factories, an oil terminal, closed military zones, quarries, a toxic waste incinerator Ramat Hovav, cell towers, a power plant, several airports, a prison, and 2 rivers of open sewage.[13]

The Tel Aviv municipality dumps its excess waste in the Negev Desert,[16] at Dudaim Dump. In 2005 the Manufacturers Association of Israel established an authority to begin marketing a project to move 60 of the 500 industrial enterprises currently active in the Tel Aviv region to the Negev.[17]

The Ramat Hovav toxic waste facility was planted in the area of Beer Sheva and Wadi el-Na'am in 1979 because the area was perceived as invulnerable to leakage. However, within a decade, cracks were found in the rock beneath Ramat Hovav.[13] From its inception, the facility developed a history of accidents and closures; in the past, regional councils regularly discovered that the evaporation pools of Ramat Hovav's Machteshim chemical factory had overflowed or that waste was leaking from drainage pipes into their reservoir. Nearly ten years after its establishment, outcrops of the chalk under Ramat Hovav showed fractures potentially leading to serious soil and groundwater contamination in the future.[18]

In 2004, the Israeli Ministry of Health released Ben Gurion University research findings describing the health problems in a 20 km vicinity of Ramat Hovav. The study, funded in large part by Ramat Hovav, found higher rates of cancer and mortality for the 350,000 people in the area, amounting to a public health crisis. Prematurely released to the media by an unknown source, the preliminary study was publicly discredited;[19] however, its final conclusions – that Bedouin and Jewish residents near Ramat Hovav are significantly more susceptible than the rest of the population to miscarriages, severe birth defects, and respiratory diseases – passed a peer review several months later.[20]

The Jewish National Fund introduced its Blueprint Negev in 2005, a $600 million project aimed at attracting 500,000 new settlers to the Negev and constructing new settlements to accommodate them. The project says it will increase the Negev's population by 250,000 new residents by 2013, improving transportation infrastructure, adding businesses and employment opportunities, preserving water resources and protecting the environment.[21] The Blueprint Negev's planned artificial desert river, swimming pools and golf courses raise concerns among environmentalists given Israel's water shortage.[22][23] The main thrust of critics' argument is that the appropriate response to overpopulation is not to recruit hundreds of thousands of additional settlers, and the answer to over-development in the north is not to build up the last open spaces in the second most-densely crowded country in the developed world; rather, what is required is an inclusive plan for the green vitalization of existing population centers in the Negev, investment in long-awaited service-provision in Bedouin villages, clean-up of its many toxic industries (such as Ramat Hovav), and the development of a viable economic plan focusing on creating job options for the unemployed rather than promoting an influx of new immigrants and creating jobs for them.[24][25][26][27]

Solar power

Main article: Solar power in Israel David Faiman of the National Solar Energy Center in front of the world's largest solar parabolic dish.

David Faiman of the National Solar Energy Center in front of the world's largest solar parabolic dish.

The Negev Desert and the surrounding area, including the Arava Valley, are the sunniest parts of Israel and little of this land is arable, which is why it has become the center of the Israeli solar industry.[28] David Faiman, an expert on solar energy, feels the energy needs of Israel's future could be met by building solar energy plants in the Negev. As director of Ben-Gurion National Solar Energy Center, he operates one of the largest solar dishes in the world.[29]

A 250 MW solar park in Ashalim, an area in the northern Negev, was in the planning stages for over five years, but it is not expected to produce power before 2013.[30] In 2008 construction began on three solar power plants near the city; two thermal and one photovoltaic.[31]

The Rotem Industrial Complex outside of Dimona, Israel has dozens of solar mirrors that focus the sun's rays on a tower that in turn heats a water boiler to create steam, turning a turbine to create electricity. Luz II, Ltd. plans to use the solar array to test new technology for the three new solar plants to be built in California for Pacific Gas and Electric Company.[32][33][34]

See also

- Beersheba

- Blueprint Negev

- Eilat

- Negev Bedouins

- Sinai Peninsula

- Southern District (Israel)

References

- ^ "Beersheba, ISR Weather". MSN. http://weather.msn.com/local.aspx?wealocations=wc:ISXX0030. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ^ "Averages and Records for Beersheba (Precipitation, Temperature and Records [Excluding January and June written in the page)"]. Israel Meteorological Service. August 2011. http://ims.gov.il/IMS/CLIMATE/LongTermInfo.

- ^ "Records Data for Israel (Data used only for January and June)". Israel Meteorological Service. http://ims.gov.il/IMS/CLIMATE/TopClimetIsrael.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Mariam Shahin. Palestine: A Guide. (2005) Interlink Books. ISBN 156656557

- ^ a b Israel Finkelstein; Avi Perevolotsky (Aug., 1990). "Processes of Sedentarization and Nomadization in the History of Sinai and the Negev". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (279): 67–88.

- ^ "Centro y periferia en el mundo antiguo. El Negev y sus interacciones con Egipto, Asiria, y el Levante en la Edad del Hierro (1200-586 A.D.) ANEM 1. SBL - CEHAO". uca.edu.ar. 2008. http://www.uca.edu.ar/esp/sec-ffilosofia/esp/docs-institutos/s-cehao/otras_public/tebes_monog_sbl.pdf.

- ^ Palestine, Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922, October 1922, J.B. Barron, Superintendent of the Census, page 10.

- ^ ibid, Census of Palestine 1922,'Explanatory note',page 4 .

- ^ Kurt Goering (Autumn, 1979). "Israel and the Bedouin of the Negev". Journal of Palestine Studies 9 (1): 3–20. doi:10.1525/jps.1979.9.1.00p0173n.

- ^ a b Manski, Rebecca (2007). "The nature of environmental injustice in bedouin urban townships: the end of self-subsistence". bustan.org. http://www.bustan.org/admin/my_documents/my_files/CD3_manski.natureofenviroinjustice.pdf.

- ^ Morris, Benny (1993) Israel's Border Wars, 1949 - 1956. Arab Infiltration, Israeli Retaliation, and the Countdown to the Suez War. Oxford University Press, ISBN 0 19 827850 0. Page 157.

- ^ Posted by: adminr on Apr 04, 04. "Uprooting Weeds". Monabaker.com. http://www.monabaker.com/pMachine/more.php?id=A1909_0_1_0_M. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ^ a b c d Manski, Rebecca (2006). "Bedouin Vilified Among Top 10 Environmental Hazards in Israel". bustan.org. http://www.bustan.org/admin/my_documents/my_files/3DC_manski.top10vilified.pdf.

- ^ "A Bedouin welcome - Israel Travel, Ynetnews". Ynetnews.com. 1995-06-20. http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-3420595,00.html. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Berger, Gali (October 12, 2005). "Sin of waste / Municipal garbage that's out of sight, out of mind". Haaretz. boker.org.il. http://www.boker.org.il//english/sinofwaste.htm.

- ^ Manor, Hadas (August 11, 2005). "Manufacturers promoting transfer of 60 factories to Negev". Globes. boker.org.il. http://www.boker.org.il//english/manufacturers.htm.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ Manski, Rebecca (2005). "The Bedouin as Worker-Nomad". bustan.org. http://www.bustan.org/subject.asp?id=25.

- ^ Sarov, Batia, and peers at Ben Gurion University: “Major congenital malformations and residential proximity to a regional industrial park including a national toxic waste site: An ecological study;” Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source 2006, 5:8; Bentov et al., licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

- ^ http://www.jnf.org/site/PageServer?pagename=negevPoints

- ^ Orenstein, Daniel (March 25, 2007). "When an ecological community is not". haaretz.com. http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/841397.html.

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ Daniel Orenstein and Steven Hamburg (November 28, 2005). "The JNF's Assault on the Negev". The Jerusalem Report. watsoninstitute.org. http://www.watsoninstitute.org/news_detail.cfm?id=383.

- ^ Manski, Rebecca (October/November 2006). "A Desert Mirage: The Rising Role of US Money in Negev Development". News from Within. alternativenews.org. http://www.alternativenews.org/images/stories/downloads/NfW_OctNov_2006/A_Desert_Mirage_Manski.pdf.

- ^ "Ohalah resolution". neohasid.org. http://www.neohasid.org/negev/resolution.

- ^ "Neohasid's Save the Negev Campaign". neohasid.org. http://neohasid.org/negev/save_the_negev/.

- ^ Ehud Zion Waldoks (March 10, 2008). "Head of Kibbutz Movement: We will not be discriminated against by the government". Jerusalem Post. http://fr.jpost.com/servlet/Satellite?cid=1205420713036&pagename=JPost%2FJPArticle%2FPrinter.

- ^ Lettice, John (January 25, 2008). "Giant solar plants in Negev could power Israel's future". The Register. http://www.theregister.co.uk/2008/01/25/faiman_negev_solar_plan/.

- ^ Yosef I. Abramowitz and David Lehreer (November 2, 2008). "The solar vote". Haaretz. http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/1033081.html.

- ^ "Solar energy could raise electricity prices". Haaretz. 6 August 2008. http://www.haaretz.com/hasen/spages/1008854.html.

- ^ "Calif. solar power test begins — in Israeli desert". Associated Press. June 12, 2008. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/25124614/. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- ^ Rabinovitch, Ari (June 11, 2008). "Israel site for California solar power test". Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/environmentNews/idUSL1110252820080611.

- ^ Washington (2008-05-08). "Building Small Prototype Homes, an Israeli Solar Experiment | News | English". Voanews.com. http://www.voanews.com/english/archive/2008-05/2008-05-08-voa17.cfm. Retrieved 2011-10-09.

External links

- Sde Boker archive of articles on the Negev

- Negev Wikitravel

- Israel's Negev Information Site

- Israel's Negev Desert

- About the Bedouin in unrecognized villages

- About changes in Bedouin life

- About Negev environmental issues

- Negev Desert Socio-Environmental Timeline

This article is about the southern region of Israel. For the light machine gun see IMI Negev.

World deserts Africa Asia - Ad-Dahna

- Arabian

- Aral Karakum

- Aralkum

- Badain Jaran

- Betpak-Dala

- Cholistan

- Dasht-e Kavir

- Dasht-e Lut

- Dasht-e Margoh

- Dasht-e Naomid

- Gurbantünggüt

- Gobi

- Hami

- Indus Valley

- Judean

- Karakum

- Kharan

- Kumtag

- Kyzyl Kum

- Lop

- Nefud

- Negev

- Ordos

- Qaidam

- Rub' al Khali

- Russian Arctic

- Registan

- Saryesik-Atyrau

- Syrian

- Taklamakan

- Tengger

- Thal

- Thar

- Tihamah

- Ustyurt Plateau

- Wahiba Sands

- Liwa

Europe North America - Alvord

- Amargosa

- Baja California

- Black Rock

- Carcross

- Channeled scablands

- Chihuahuan

- Escalante

- Forty Mile

- Gran Desierto de Altar

- Great Basin

- Great Salt Lake

- Great Sandy

- Jornada del Muerto

- Kaʻū

- Lechuguilla

- Mojave

- North American Arctic

- Owyhee

- Painted Desert

- Red Desert

- Sevier

- Smoke Creek

- Sonoran

- Tule (Arizona)

- Tule (Nevada)

- Yp

- Yuha

- Yuma

Australia South America Polar regions New Zealand South District of Israel Cities

Local councils Ar'arat an-Naqab · Hura · Kuseife · Lakiya · Lehavim · Meitar · Mitzpe Ramon · Omer · Shaqib al-Salam · Tel as-Sabi · YeruhamRegional councils Abu Basma · Be'er Tuvia · Bnei Shimon · Central Arava · Eshkol · Hevel Eilot · Hof Ashkelon · Lakhish · Merhavim · Ramat HaNegev · Sdot Negev (Azata) · Sha'ar HaNegev · Shafir · Tamar · YoavSee also Other sub-divisions: Center District · Haifa District · Jerusalem District · Judea and Samaria Area · North District · Tel Aviv DistrictCategories:- South District (Israel)

- Regions of Israel

- Deserts of Israel

- Hebrew Bible places

- New Testament places

- Visitor attractions in Israel

- Ergs

- Negev

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.