- New Trade Theory

-

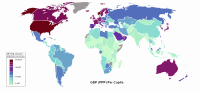

Economics  Economies by region

Economies by regionGeneral categories Microeconomics · Macroeconomics

History of economic thought

Methodology · Mainstream & heterodoxTechnical methods Mathematical economics

Game theory · Optimization

Computational · Econometrics

Experimental · National accountingFields and subfields Behavioral · Cultural · Evolutionary

Growth · Development · History

International · Economic systems

Monetary and Financial economics

Public and Welfare economics

Health · Education · Welfare

Population · Labour · Managerial

Business · Information

Industrial organization · Law

Agricultural · Natural resource

Environmental · Ecological

Urban · Rural · Regional · GeographyLists Business and Economics Portal New Trade Theory (NTT) is a collection of economic models in international trade which focuses on the role of increasing returns to scale and network effects, which were developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

New Trade theorists relaxed the assumption of constant returns to scale, and some argue that using protectionist measures to build up a huge industrial base in certain industries will then allow those sectors to dominate the world market.

Less quantitative forms of a similar "infant industry" argument against totally free trade have been advanced by trade theorists since at least 1848 (see: History of free trade.)

Contents

The theory's impact

Although there was nothing particularly 'new' about the idea of protecting 'infant industries' (an idea offered in theory since the 18th century, and in trade policy since the 1880s) what was new in "New Trade Theory" was the rigour of the mathematical economics used to model the increasing returns to scale, and especially the use of the network effect to argue that the formation of important industries was path dependent in a way which industrial planning and judicious tariffs might control.

The models developed were highly technical, and predicted the possibilities of national specialization-by-industry observed in the industrial world (movies in Hollywood, watches in Switzerland, etc.). The story of path-dependent industrial concentrations can sometime lead to monopolistic competition or even situations of oligopoly.

Some economists, such as Ha-Joon Chang, had argued that free trade would have prevented the development of the Japanese auto industries in the 1950s, when quotas and regulations prevented import competition. Japanese companies were encouraged to import foreign production technology but were required to produce 90% of parts domestically within five years. It is said[who?] that the short-term hardship of Japanese consumers (who were unable to buy the superior vehicles produced by the world market) was more than compensated for by the long-term benefits to producers, who gained time to out-compete their international rivals.[1]

Econometric testing

The econometric evidence for NTT was mixed, and highly technical. Due to the time-scales required, and the particular nature of production in each 'monopolizable' sector, statistical judgements were hard to make. In many ways, the available data have been too limited to produce a reliable test of the hypothesis, which doesn't require arbitrary judgements from the researchers.

Japan is cited as evidence of the benefits of "intelligent" protectionism, but critics[who?] of NTT have argued that the empirical support post-war Japan offers for beneficial protectionism is unusual, and that the NTT argument is based on a selective sample of historical cases. Although many examples (like Japanese cars) can be cited where a 'protected' industry subsequently grew to world status, regressions on the outcomes of such "industrial policies" (which include failures) have been less conclusive; some findings suggest that sectors targeted by Japanese industrial policy had decreasing returns to scale and did not experience productivity gains.[2]

History of the theory's development

The theory was initially associated with Paul Krugman in the late 1970s; Krugman claims that he heard about monopolistic competition from Robert Solow. Looking back in 1996 Krugman wrote that International economics a generation earlier had completely ignored returns to scale. "The idea that trade might reflect an overlay of increasing-returns specialization on comparative advantage was not there at all: instead, the ruling idea was that increasing returns would simply alter the pattern of comparative advantage." In 1976, however, MIT-trained economist Victor Norman had worked out the central elements of what came to be known as the Helpman-Krugman theory. He wrote it up and showed it to Avinash Dixit. However, they both agreed the results were not very significant. Indeed Norman never had the paper typed up, much less published. Norman's formal stake in the race comes from the final chapters of the famous Dixit-Norman book (Theory of International Trade : A Dual, General Equilibrium Approach, ISBN 0-521-29969-1).

James Brander, a PhD student at Stanford at the time, was undertaking similarly innovative work using models from industrial organisation theory— cross-hauling— to explain two-way trade in similar products.

See also

- General equilibrium

- Endogenous growth theory was developed at a similar time to NTT, and is linked through the idea that industrial and trade policy can affect over-all productivity growth.

- Home-market effect

External links

- On The Smithian Origins Of "New" Trade And Growth Theories, Aykut Kibritcioglu Ankara University shows that Adam Smith's "increasing returns to scale" conception of international trade anticipated NTT by two hundred years.

- Krugman acknowledges NTT's debt to Ohlin. He writes that Ohlin may have lacked the modelling technology necessary to incorporate increasing returns to scale into the Heckscher-Ohlin model, but that his book Interregional and International Trade, discusses the consideration qualitatively.

References

- ^ MacEwan, Arthur (1999). Neo-liberalism or democracy?: economic strategy, markets, and alternatives for the 21st century. Zed Books. ISBN 1-85649-725-9. http://books.google.de/books?id=w9CH8Aj9StkC&printsec=frontcover. Retrieved 2009-04-04The rapid post-war industrialization in Japan is documented in this book. The book also details the Keynesian case against free trade, on the grounds of the Poor’s under-consumption, see[dead link]).

- ^ Richard Beason and David E. Weinstein (1996), "Growth, Economies of Scale, and Targeting in Japan (1955-1990)" The Review of Economics and Statistics, Vol. 78, No. 2 (May, 1996), pp. 286-295.

Categories:- International economics

- International trade

- Economic theories

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.