- Chloroquine

-

Chloroquine

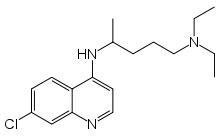

Systematic (IUPAC) name N'-(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)-N,N-diethyl-pentane-1,4-diamine Clinical data Trade names Aralen AHFS/Drugs.com monograph Licence data US FDA:link Pregnancy cat. ? Legal status ℞-only (US) Pharmacokinetic data Metabolism Liver Half-life 1-2 months Identifiers CAS number 54-05-7

ATC code P01BA01 PubChem CID 2719 DrugBank APRD00468 ChemSpider 2618

UNII 886U3H6UFF

KEGG D02366

ChEBI CHEBI:3638

ChEMBL CHEMBL76

Chemical data Formula C18H26ClN3 Mol. mass 319.872 g/mol SMILES eMolecules & PubChem  (what is this?) (verify)

(what is this?) (verify)Chloroquine (

/ˈklɔrəkwɪn/) is a 4-aminoquinoline drug used in the treatment or prevention of malaria.

/ˈklɔrəkwɪn/) is a 4-aminoquinoline drug used in the treatment or prevention of malaria.Contents

History

Chloroquine (CQ), N'-(7-chloroquinolin-4-yl)-N,N-diethyl-pentane-1,4-diamine, was discovered in 1934 by Hans Andersag and co-workers at the Bayer laboratories who named it "Resochin". It was ignored for a decade because it was considered too toxic for human use. During World War II, United States government-sponsored clinical trials for anti-malarial drug development showed unequivocally that CQ has a significant therapeutic value as an anti-malarial drug. It was introduced into clinical practice in 1947 for the prophylactic treatment of malaria.[1]

Uses

- It has long been used in the treatment or prevention of malaria. After the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum started to develop widespread resistance to chloroquine,[2][3] new potential utilisations of this cheap and widely available drug have been investigated. Chloroquine has been extensively used in mass drug administrations which may have contributed to the emergence and spread of resistance.

- As it mildly suppresses the immune system, it is used in some autoimmune disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus erythematosus.

- Chloroquine is in clinical trials as an investigational antiretroviral in humans with HIV-1/AIDS and as a potential antiviral agent against chikungunya fever.[4]

- The radiosensitizing and chemosensitizing properties of chloroquine are beginning to be exploited in anticancer strategies in humans.[5][6]

Pharmacokinetics

Chloroquine has a very high volume of distribution, as it diffuses into the body's adipose tissue. Chloroquine and related quinines have been associated with cases of retinal toxicity, particularly when provided at higher doses for longer time frames. Accumulation of the drug may result in deposits that can lead to blurred vision and blindness. With long-term doses, routine visits to an ophthalmologist are recommended.

Chloroquine is also a lysosomotropic agent, meaning that it accumulates preferentially in the lysosomes of cells in the body. The pKa for the quinoline nitrogen of chloroquine is 8.5, meaning that it is ~10% deprotonated at physiological pH as calculated by the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation. This decreases to ~0.2% at a lysosomal pH of 4.6. Because the deprotonated form is more membrane-permeable than the protonated form, a quantitative "trapping" of the compound in lysosomes results.

(Note that a quantitative treatment of this phenomenon involves the pKas of all nitrogens in the molecule; this treatment, however, suffices to show the principle.)

The lysosomotropic character of chloroquine is believed to account for much of its anti-malarial activity; the drug concentrates in the acidic food vacuole of the parasite and interferes with essential processes. Its lysomotropic properties further allow for its utilization in in vitro experiments pertaining to intracellular lipid related diseases[7][8] , autophagy and apoptosis[9] .

Malaria prevention

Chloroquine can be used for preventing malaria from Plasmodium vivax, ovale and malariae. Popular drugs based on chloroquine phosphate (also called nivaquine) are Chloroquine FNA, Resochin and Dawaquin. Many areas of the world have widespread strains of chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum, so other antimalarials like mefloquine or atovaquone may be advisable instead. Combining chloroquine with proguanil may be more effective against chloroquine-resistant Plasmodium falciparum than treatment with chloroquine alone, but is no longer recommended by the CDC due to the availability of more effective combinations.[10] For children 14 years of age or below, the dose of chloroquine is 600 mg per week.[citation needed]

Adverse effects

At the doses used for prevention of malaria, side-effects include gastrointestinal problems, stomach ache, itch, headache, nightmares and blurred vision.

Chloroquine-induced itching is very common among black Africans (70%), but much less common in other races. It increases with age, and is so severe as to stop compliance with drug therapy. It is increased during malaria fever, its severity correlated to the malaria parasite load in blood. There is evidence that it has a genetic basis and is related to chloroquine action with opiate receptors centrally or peripherally.[11]

When doses are extended over a number of months, it is important to watch out for a slow onset of "changes in moods" (i.e., depression, anxiety). These may be more pronounced with higher doses used for treatment. Chloroquine tablets have an unpleasant metallic taste.

A serious side-effect is also a rare toxicity in the eye (generally with chronic use), and requires regular monitoring even when symptom-free.[12] The daily safe maximum doses for eye toxicity can be computed from one's height and weight using this calculator.[13] The use of Chloroquine has also been associated with the development of Central Serous Retinopathy.

Chloroquine is very dangerous in overdose. It is rapidly absorbed from the gut. In 1961, studies were published showing that three children who took overdoses died within 2 1⁄2 hours of taking the drug. While the amount of the overdose was not cited, it is known that the therapeutic index for chloroquine is small.[14]

According to research published in the journal PloS One, an overuse of Chloroquine treatment has led to the development of a specific strain of E. coli that is now resistant to the powerful antibiotic Ciprofloxacin.[15]

A metabolite of chloroquine - hydroxycloroquine - has a long half life (32–56 days) in blood and a large volume of distribution (580-815 L/kg).[16] The theraputic, toxic and lethal ranges are usually considered to be 0.03 to 15 mg/L, 3.0 to 26 mg/L and 20 to 104 mg/L respectively. However non toxic cases have been reported in the range 0.3 to 39 mg/L suggesting that individual tolerance of this agent may be more variable than previously recognised.[16]

Mechanism of action

Antimalarial

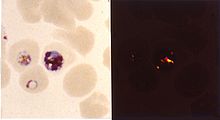

Inside red blood cells, the malarial parasite must degrade hemoglobin to acquire essential amino acids, which the parasite requires to construct its own protein and for energy metabolism. Digestion is carried out in a vacuole of the parasite cell.

During this process, the parasite produces the toxic and soluble molecule heme. The heme moiety consists of a porphyrin ring called Fe(II)-protoporphyrin IX (FP). To avoid destruction by this molecule, the parasite biocrystallizes heme to form hemozoin, a non-toxic molecule. Hemozoin collects in the digestive vacuole as insoluble crystals.

Chloroquine enters the red blood cell, inhabiting parasite cell, and digestive vacuole by simple diffusion. Chloroquine then becomes protonated (to CQ2+), as the digestive vacuole is known to be acidic (pH 4.7); chloroquine then cannot leave by diffusion. Chloroquine caps hemozoin molecules to prevent further biocrystallization of heme, thus leading to heme buildup. Chloroquine binds to heme (or FP) to form what is known as the FP-Chloroquine complex; this complex is highly toxic to the cell and disrupts membrane function. Action of the toxic FP-Chloroquine and FP results in cell lysis and ultimately parasite cell autodigestion. In essence, the parasite cell drowns in its own metabolic products.[17]

Resistance

Since the first documentation of P. falciparum chlorquine resistance in the 1950s, resistant strains have appeared throughout East and West Africa, South East Asia, and South America. The effectiveness of chloroquine against P. falciparum has declined as resistant strains of the parasite evolved. They effectively neutralize the drug via a mechanism that drains chloroquine away from the digestive vacuole. CQ-Resistant cells efflux chloroquine at 40 times the rate of CQ-Sensitive cells; the related mutations trace back to transmembrane proteins of the digestive vacuole, including sets of critical mutations in the PfCRT gene (Plasmodium falciparum Chloroquine Resistance Transporter). The mutated protein, but not the wild-type transporter, transports chloroquine when expressed in Xenopus oocytes and is thought to mediate chloroquine leak from its site of action in the digestive vacuole.[18] Resistant parasites also frequently have mutated products of the ABC transporter PfMDR1 (Plasmodium falciparum Multi-Drug Resistance gene) although these mutations are thought to be of secondary importance compared to Pfcrt. Verapamil, a Ca2+ channel blocker, has been found to restore both the chloroquine concentration ability as well as sensitivity to this drug. Recently an altered chloroquine-transporter protein CG2 of the parasite has been related to chloroquine resistance, but other mechanisms of resistance also appear to be involved.[19]

Research on the mechanism of chloroquine and how the parasite has acquired chloroquine resistance is still ongoing, and there are likely to be other mechanisms of resistance.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

Against rheumatoid arthritis, it operates by inhibiting lymphocyte proliferation, phospholipase A[disambiguation needed

], antigen presentation in dendritic cells, release of enzymes from lysosomes, release of reactive oxygen species from macrophages, and production of IL-1.

], antigen presentation in dendritic cells, release of enzymes from lysosomes, release of reactive oxygen species from macrophages, and production of IL-1.Antiviral

As an antiviral agent, it impedes the completion of the viral life cycle by inhibiting some processes occurring within intracellular organelles and requiring a low pH. As for HIV-1, chloroquine inhibits the glycosylation of the viral envelope glycoprotein gp120, which occurs within the Golgi apparatus.

Other studies suggest quite the opposite, with chloroquine being a potent inhibitor of interferons and enhancer of viral replication.[20]

Antitumor

The mechanisms behind the effects of chloroquine on cancer are currently being investigated. The best-known effects (investigated in clinical and pre-clinical studies) include radiosensitizing effects through lysosome permeabilization, and chemosensitizing effects through inhibition of drug efflux pumps (ATP-binding cassette transporters) or other mechanisms (reviewed in the second-to-last reference below).

References

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/malaria/history/index.htm#chloroquine

- ^ Plowe CV (2005). "Antimalarial drug resistance in Africa: strategies for monitoring and deterrence". Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 295: 55–79. doi:10.1007/3-540-29088-5_3. PMID 16265887.

- ^ Uhlemann AC, Krishna S (2005). "Antimalarial multi-drug resistance in Asia: mechanisms and assessment". Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 295: 39–53. doi:10.1007/3-540-29088-5_2. PMID 16265886.

- ^ Savarino A, Boelaert JR, Cassone A, Majori G, Cauda R (November 2003). "Effects of chloroquine on viral infections: an old drug against today's diseases?". Lancet Infect Dis 3 (11): 722–7. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00806-5. PMID 14592603. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1473309903008065.

- ^ Savarino A, Lucia MB, Giordano F, Cauda R (October 2006). "Risks and benefits of chloroquine use in anticancer strategies". Lancet Oncol. 7 (10): 792–3. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70875-0. PMID 17012039. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1470-2045(06)70875-0.

- ^ Sotelo J, Briceño E, López-González MA (March 2006). "Adding chloroquine to conventional treatment for glioblastoma multiforme: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ann. Intern. Med. 144 (5): 337–43. PMID 16520474.

"Summaries for patients. Adding chloroquine to conventional chemotherapy and radiotherapy for glioblastoma multiforme". Ann. Intern. Med. 144 (5): I31. March 2006. PMID 16520470. - ^ Chen, Patrick; Gombart, Z and Chen J (2011). "Chloroquine treatment of ARPE-19 cells leads to lysosome dilation and intracellular lipid accumulation: possible implications of lysosomal dysfunction in macular degeneration". Cell & Bioscience 1 (10). http://www.cellandbioscience.com/content/1/1/10.

- ^ Kurup, Pradeep; Zhang Y, Xu J, et al. (2010). "β-Mediated NMDA Receptor Endocytosis in Alzheimer's Disease Involves Ubiquitination of the Tyrosine Phosphatase STEP61". Neurobiology of Disease 30 (17). http://www.jneurosci.org/content/30/17/5948.short.

- ^ Kim, Ella; Wustenberg R, Rusbam A, et al (2010). "Chloroquine activates the p53 pathway and induces apoptosis in human glioma cells". Neuro-oncology 12 (4). http://neuro-oncology.oxfordjournals.org/content/12/4/389.short.

- ^ CDC. Health information for international travel 2001-2002. Atlanta, Georgia: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, 2001.

- ^ Ajayi AA (September 2000). "Mechanisms of chloroquine-induced pruritus". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 68 (3): 336. PMID 11014416.

- ^ Yam JC, Kwok AK (August 2006). "Ocular toxicity of hydroxychloroquine". Hong Kong Med J 12 (4): 294–304. PMID 16912357. http://www.hkmj.org/abstracts/v12n4/294.htm.

- ^ "numericalexample.com - Determine the safe dose of medicins: Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil)". http://www.numericalexample.com/content/view/24/33. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ^ Cann HM, Verhulst HL (1 January 1961). "Fatal acute chloroquine poisoning in children" (abstract). Pediatrics 27 (1): 95–102. PMID 13690445. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/abstract/27/1/95?ijkey=0c507c09d8450f8c8bbadf109d6428e93ad2619f&keytype2=tf_ipsecsha.

- ^ Davidson RJ, Davis I, Willey BM (2008). Frenck, Robert. ed. "Antimalarial therapy selection for quinolone resistance among Escherichia coli in the absence of quinolone exposure, in tropical South America". PLoS ONE 3 (7): e2727. Bibcode 2008PLoSO...3.2727D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002727. PMC 2481278. PMID 18648533. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2481278.

- ^ a b Molina DK (2011) Postmortem hydroxychloroquine concentrations in nontoxic cases. Am J Forensic Med Pathol

- ^ Hempelmann E. (2007). "Hemozoin biocrystallization in Plasmodium falciparum and the antimalarial activity of crystallization inhibitors". Parasitol Research 100 (4): 671–676. doi:10.1007/s00436-006-0313-x. PMID 17111179. http://parasitology.informatik.uni-wuerzburg.de/login/n/h/j_436-100-4-2006-11-17-313.html.

- ^ Martin RE, Marchetti RV, Cowan AI et al.(September 2009). "Chloroquine transport via the malaria parasite's chloroquine resistance transporter". Science 325(5948): 1680-2:

- ^ Essentials of medical pharmacology fifth edition 2003,reprint 2004, published by-Jaypee Brothers Medical Publisher Ltd, 2003,KD tripathi, page 739,740.

- ^ http://www.malariasite.com/malaria/malariainaids.htm

External links

Antiparasitics – antiprotozoal agents – Chromalveolate antiparasitics (P01) Alveo-

lateIndividual

agentsOtherSulfadoxine • sulfamethoxypyrazineCoformulationFansidar# (sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine)OtherCombi-

nationsartemether-lumefantrine#

artesunate-amodiaquine (ASAQ)

artesunate-mefloquine (ASMQ)

dihydroartemisinin-piperaquine

artesunate-pyronaridineOther combinations

(not co-formulated)artesunate/SP • artesunate/mefloquine •

quinine/tetracycline • quinine/doxycycline • quinine/clindamycinHetero-

kontSpecific antirheumatic products / DMARDs (M01C) Quinolines Gold preparations Other Penicillamine #/Bucillamine • Chloroquine #/Hydroxychloroquine • Leflunomide • Sulfasalazine # • antifolate (Methotrexate #) • thiopurine (Azathioprine) #M: JNT

anat(h/c, u, t, l)/phys

noco(arth/defr/back/soft)/cong, sysi/epon, injr

proc, drug(M01C, M4)

Categories:- Antimalarial agents

- Antirheumatic products

- Quinolines

- Organochlorides

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.