- Islam in Australia

-

Part of a series on

Islam by countryThe AmericasIslam in Australia is a small minority religious grouping, but fourth largest after all forms of Christianity (64%), irreligion (18.7%) and Buddhism (2.1%), excluding 11.2% who failed to answer at the last census. According to the 2006 census, approximately 340,392 people, or 1.71%[1] of the total Australian population were Muslims.

While the Australian Muslim community is defined largely by religious belonging, the Muslim community is fragmented further by being the most racially, ethnically, culturally and linguistically diverse religious grouping in Australia, with members from every ethnic and racial background, including Anglo-Celtic Australian Muslims. Members of the Australian Muslim community thus also espouse parallel non-religious ethnic identities with related non-Muslim counterparts, either within Australia or abroad.

Although Islam's presence in Australia is often perceived to be recent by Australian non-Muslims, adherents of Islam from what is today Indonesia had in fact been visiting the Great southern land prior to colonial era settlement of European Christians. For several centuries these Muslims had traded with coastal Aboriginal peoples of the north. The common misconception among Australian non-Muslims that Islam is new to Australia is due mostly to knowledge of Islam and Muslims limited only to the recent migratory waves from the Middle East and the Balkans of Europe, North Africa, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and most recently from Sub-Saharan Africa.

Contents

History

Pre-European Australia

The first Muslims in Australia were traders from ethnic groups indigenous to the Indonesian archipelago.[2] The Macassan and Bugis traders from Indonesia may have had a relationship with the Indigenous people of northern Australia, and their language influenced Indigenous Australians of different tribes.[3]

Macassan trepangers and Bugis traders from Sulawesi (formerly Celebes) visited the coast of northern Australia for hundreds of years prior to arrival of Europeans in Australia to fish for trepang (also known as sea cucumber or "sandfish"), a marine invertebrate prized for its culinary and medicinal values in Chinese markets.

During the voyages the Macassans left their mark on the people of northern Australia — in language, art, economy and even genetics in the descendants of both Macassan and Indigenous Australian ancestors that are now found on both sides of the Arafura and Banda Seas.[4]

First Fleet

The early fleets of settlers used Muslims from coastal Africa and the islands and territories under the British Empire, for labour and as navigators.

19th century

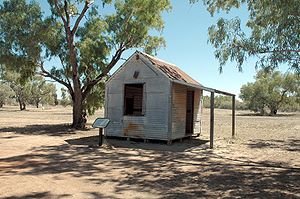

Between 1860 and the 1890s a number of Central Asians came to Australia to work as "Afghan" camel drivers. Camels were first imported into Australia in 1840, initially for exploring the arid interior (see Australian camel), and later for the camel trains that were uniquely suited to the demands of Australia's vast deserts. The first camel drivers arrived in Melbourne in June 1860, when eight Muslims and Hindus arrived with the camels for the Burke and Wills expedition. The next arrival of camel drivers was in 1866 when 31 men from Rajasthan and Baluchistan arrived in South Australia with camels for Thomas Elder. Although they came from several countries, they were usually known in Australia as 'Afghans' and they brought with them the first formal establishment of Islam in Australia.[5]

Cameleers settled in the areas near Alice Springs and other areas of the Northern Territory and inter-married with the Indigenous population. The Adelaide to Darwin railway is named The Ghan (short for The Afghan) in their memory.[6]

The first mosque in Australia was built in 1861 at Marree in South Australia.[7] The Great Mosque of Adelaide was built in 1888 by the descendants of the Afghan cameleers.

During the 1870s, Muslim Malay divers were recruited through an agreement with the Dutch to work on Western Australian and Northern Territory pearling grounds. By 1875, there were 1800 Malay divers working in Western Australia. Most returned to their home countries.

Early 20th century

In the early twentieth century, Muslims of non-European descent experienced many difficulties in emigrating to Australia because of a government policy which limited immigration on the basis of links with Great Britain and Ireland. Known as the White Australia Policy, politicians of the era claimed that non-white immigrants would cause social disharmony.[8][9]

However, some Muslims still managed to come to Australia. In the 1920s and 1930s Albanian Muslims were accepted, whose European heritage made them more compatible with the White Australia Policy. Albanian Muslims built the first mosque in Shepparton, Victoria in 1960 and the first mosque in Melbourne in 1963.

Post World War II

The perceived need for population growth and economic development in Australia led to the broadening of Australia’s immigration policy in the post-World War II period. This allowed for the acceptance of a number of displaced Muslims who began to arrive from Europe mainly from the Balkans (i.e. Bosnia-Herzegovina)

Moreover, between 1967 and 1971, approximately 10,000 Turks settled in Australia under an agreement between Australia and Turkey. This was the first Muslim community of Middle Eastern origin to settle in Australia. Almost all of these people went to Melbourne and Sydney.

From the 1970s onwards, there was a significant shift in the government’s attitude towards immigration. Instead of trying to make newer foreign nationals assimilate and forgo their heritage, the government became more accommodating and tolerant of differences by adopting a policy of multiculturalism.

By the beginning of the twenty-first century, Muslims from more than sixty countries had settled in Australia. While a very large number of them come from Bosnia, Turkey, and Lebanon, there are Muslims from Indonesia, Malaysia, Iran, Fiji, Albania, Sudan, Egypt, the Palestinian territories, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Bangladesh, among others.

Late 20th century

History Mosques List of Mosques

Organisations Australian Federation of Islamic Councils

Lebanese Moslems Association

Islamic Information and Services

Network of Australasia

Muslim Council of New South WalesGroups Afghan · Arab · Bangladeshi

Bosnian · Indonesian · Iranian

Iraqi · Lebanese · Malay

Pakistani · TurkishCulture Other topics Larger-scale Muslim migration began in 1975 with the migration of Lebanese Muslims, which rapidly increased during the Lebanese Civil War from 22,311 or 0.17% of the Australian population in 1971, to 45,200 or 0.33% in 1976.[10] Lebanese Muslims are still the largest and highest-profile Muslim group in Australia, although Lebanese Christians form a majority of Lebanese Australians, outnumbering their Muslim counterparts at a 6 to 4 ratio.

Lebanese Muslims form the core of Australia's Muslim Arab population, particularly in Sydney where most Arabs in Australia live. Approximately 3.4% of Sydney's population are Muslim. Adherents of the Sunni denomination of Islam are concentrated in the suburb of Lakemba and surrounding areas such as Punchbowl, Wiley Park, Bankstown and Auburn. Adherents of the Shi'a denomination of Islam is centred in the St George region of Sydney, Campbelltown, Fairfield, also Auburn and Liverpool, with the al-Zahra Mosque being built at Arncliffe in 1983,[11] However there are also a small number of adherents to the Ahmadiyya sect.[12] During the 1980s the Australian Muslim population increased from 76,792 or 0.53% of the Australian population in 1981, to 109,523 or 0.70% in 1986.[10]

There are also Somali populations scattered throughout Australia who fled their country from the start of the Somali civil war in 1991. The general increase of the Muslim population in this decade was from 147,487 or 0.88% of the Australian population in 1991, to 200,885 or 1.12% in 1996.[10]

In 2005, tensions between Lebanese Australian Muslims and Anglo-Celtic Australian non-Muslims caused the 2005 Cronulla riots. At this time the overall Muslim population in Australia had grown from 281,600 or 1.50% of the general Australian population in 2001, to 340,400 or 1.71% in 2006. The growth of Muslim population at this time was recorded as 3.88% compared to 1.13% for the general Australian population.[10]

Many Muslims living in Melbourne are Bosnian Muslims and Turkish Muslims. Melbourne's Australian Muslims live primarily in the northern suburbs surrounding Broadmeadows (mostly Turkish) and a few in the outer southern suburbs such as Noble Park and Dandenong (mainly Bosnian Muslim).

Very few Muslims live in regional areas with the exceptions of the sizeable Turkish and Albanian community in Shepparton, Victoria and Malays in Katanning, Western Australia. A community of Iraqis have settled in Cobram on the Murray River in Victoria.[13]

Perth also has a Muslim community focussed in and around the suburb of Thornlie, where there is a Mosque. Perth's Australian Islamic School has around 2,000 students on three campuses.

Mirrabooka and neighbouring Girrawheen contain predominantly Bosnian Muslim communities. The oldest mosque in Perth is the Perth Mosque on William Street in Northbridge. It has undergone many renovations although the original section still remains. Other mosques in Perth are located in Rivervale, Mirrabooka, Beechboro and Hepburn.

There are also communities of Muslims from Turkey, the Indian subcontinent (Pakistan, India and Bangladesh) and South-East Asia, in Sydney and Melbourne (the Turkish communities around Auburn, New South Wales and Meadow Heights and Roxburgh Park and the South Asian communities around Parramatta. Indonesian Muslims, are more widely distributed in Darwin.

There is a deep split within the Australian Muslim community. Many of the Muslims in New South Wales are Arabs but there are also Turkish and Bosnian Muslim communities, while Victoria has predominantly Bosnian, Turkish or Albanian Muslims.

The mainly moderate Bosnian Australian community refused to accept the fundamentalist Taj El-Din Hilaly (an Arab born in Egypt) as Australia's mufti. Victorian Imams do not recognise Hilaly. Hilaly, who was criticised by Australian politicians for allegedly broaching Holocaust denial, is no longer recognised as a mufti.

Present day Islam in Australia

Aboriginal Muslims

Islamic contact with the Aboriginal population may be older than its contact with Christianity, which had a more profound impact. The first contacts between Aborigines and Muslims include some of the oldest contacts Aborigines had with the outside world itself.[14] Most of the people neighbouring Australia are Muslim (see Macassan contact with Australia).

As of 2003, the growing community of indigenous Aboriginal Muslims, was conservatively estimated as 1000 individuals.[15] Others are descendants of Afghan cameleers or, as in the Arnhem Land people, have Macassan ancestry.[16] The boxer Anthony Mundine is a member of this community.[17]

Population statistics

The following is a breakdown of the country of origin of Muslims in Australia from 2001:[18]

- Australia: 36%

- Lebanon: 10%

- Turkey: 8.5%

- Bosnia-Herzegovina: 4.0%

- Afghanistan: 3.5%

- Pakistan: 3.2%

- Indonesia: 2.9%

- Iraq: 2.8%

- Bangladesh: 2.7%

- Iran: 2.3%

- Fiji: 2.0%

There were 281,578 Muslims recorded in this survey; in the 2006 census the population had grown to 340,392.[19]

The distribution by state of the nation's Islamic followers has New South Wales with 50% of the total number of Muslims, followed by Victoria (33%), Western Australia (7%), Queensland (5%), South Australia (3%), ACT (1%) and both Northern Territory and Tasmania sharing 0.3%.

The majority of people who reported Islam as their religion in the 2006 Census were born overseas: 58% (198,400).[19] Of all persons affiliating with Islam in 2006 almost 9% were born in Lebanon and 7% were born in Turkey.[20]

When comparing top three religious affiliations of residents in the top 15 countries of birth of migrants to Australia compared with that of Australian residents born in those countries (2006 census), the following results relate to Islamic population proportions:[19]

Country of origin Proportion of people with Islam or Muslim as their religious affiliation in country Proportion of Australian residents born in that country with Islam or Muslim as their religious affiliation India 13% are Muslim Islam not in top 3 responses for religious affiliation Philippines 5% Islam Islam not in top 3 responses for religious affiliation Greece 1.3% Muslim Islam not in top 3 responses for religious affiliation Germany 4% Islam Islam not in top 3 responses for religious affiliation South Africa 1% Islam Islam not in top 3 responses for religious affiliation Malaysia 60% Islam Islam not in top 3 responses for religious affiliation. Malaysia has a 60% Muslim population, but only 5% of Malaysian-born Australians cited Islam as their religion.[19] Netherlands 6% Islam Islam not in top 3 responses for religious affiliation Lebanon 60% Muslim 40% Islam Muslims in contemporary Australian society

There are developed trade links between Australia and several Muslim countries, particularly Middle Eastern, for instance through the export of halal meat. The meat export industry is regulated in Australia and managed by the Meat and Livestock Association.

Of the thousands of international students studying in Australia, a number[quantify] are Muslims from countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan.

Since the 2001 World Trade Center attacks in New York, and the 2005 Bali bombings, Islam and its place in Australian society has been the subject of much public debate.[21] A number of forums and meetings have been held about the problem of extremist groups or ideology within the Australian Islamic community.[22][23] Politicians and the media have taken a robust approach to tackling militant Islam at home and abroad.[24] Jamaah Islamiyah’s bomb attack on the Bali tourist resort in Indonesia on 12 October 2002, killed 88 Australians. Some 20 Australians were killed on 9/11. Australia’s Prime Minister, John Howard, was in Washington on 9/11. Australia immediately committed special forces to the war against the Taliban and Al-Qaeda in Afghanistan. After the 7/7 attacks in London, Mr Howard established a Muslim Community Reference Group and said that no radicals would be invited to join. When al-Hilali (the Mufti of Australia) suggested Holocaust denial, Andrew Robb, the Australian Parliamentary Secretary for Multiculturalism, said he would not be reappointed to the group. Peter Costello (Mr Howard’s deputy)warned that, if the radical Muslim cleric Abdul Nasser Ben Brika really wanted to live under Sharia law, he might choose voluntary deportation to Iran. In October 2006, Muslim cleric Taj El-Din Hilaly compared women who do not wear the Islamic veil to "uncovered meat", implying that they were responsible for gang rapes perpetrated by Muslims; "if the meat was covered, the cats wouldn't roam around it".[25][26][27] Hiali's comments echoed earlier comments placing the blame on women for rape made by Sheik Feiz Mohammed.[28][29] Angry responses to the comments were made from Muslim women as well as non-Muslim figures.[30] A similar incident occurred in January 2008, when cleric Samir Abu Hamza, leader of the Islamic Information and Services Network of Australasia, told his male followers they can beat and rape their wives if they're disobedient.[31] He also denounced Australian culture as one of beer, gambling, and prostitutes.[32] These comments were condemned by both the Muslim community and the public at large;[33] Prime Minister Kevin Rudd demanded an apology for the comments, saying "Australia will not tolerate these sorts of remarks. They don't belong in modern Australia, and he should stand up, repudiate them and apologise".[34] Radical Muslims — or their parents or grandparents — have come mostly from Lebanon or North Africa, with some from the sub-continent. In addition there are a few Australian converts to the cause — the best known of whom are David Hicks, held at Guantanamo Bay, and Jack Thomas. As part of the broader issue of women's rights under Islam (particularly in light of the misogynistic statements by Islamic leaders) the perceived or real gender inequality in Islam has often been the focal point of criticism in Australia via comparisons to the situation of women in Islamic nations. Muslim women face hurdles both from within the Muslim community and from the wider community.[21][35]

Unemployment rates amongst Muslims born overseas are higher than those born in Australia. Average wages of Muslims are much lower than those of the national average, with just 5% of Muslims earning over $1000 a week compared to the average of 11%.[21]

A 2004 report from the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission showed that many Muslim Australians felt the Australian media was unfairly critical of, and often vilified their community due to generalisations of terrorism and the emphasis on crime. The use of ethnic or religious labels in news reports about crime was thought to stir up racial tensions.[36]

Notable Muslim Australians

- Sh. Mohammad Omran, Abu Ayman

- Sh. Khaled Issa

- Sh. Abdulsalam Zoud

- Sh. Feiz Muhammad

- Adeeb Kamal Ad-Deen

- Waleed Aly

- Taj El-Din Hilaly

- John Ilhan

- Fehmi Naji

- Osamah Sami

- Ed Husic

- Hazem El-Masri

- Bachar Houli

- Usman Khawaja

- Ahmed Fahour

- Irfan Yusuf

Islamic schools and universities

- The Islamic Sciences and Research Academy of Australia (ISRA), University and School, New South Wales

- Al Amanah College, New South Wales

- AlKauthar Institute, Victoria, New South Wales

- Al-Hidayah Islamic School, Western Australia

- Darul Ulum College of Victoria, Australia

- Al-Faisal College, New South Wales

- Unity Grammar College, Australia, New South Wales

- Al-Noori Muslim Primary School, New South Wales

- Qibla College, New South Wales

- Al Zahrah College, New South Wales

- Arkana College, New South Wales

- Australian International Academy (formerly King Khalid Islamic College of Victoria), Victoria

- Australian International Islamic College, Queensland

- Australian Islamic College, Western Australia

- Australian Islamic College of Sydney New South Wales

- East Preston Islamic College, Victoria

- Ilim College of Australia, Victoria

- Islamic College of Brisbane, Queensland

- Islamic College of South Australia, South Australia

- King Abdul Aziz School, New South Wales

- Langford Islamic College, Western Australia

- Malek Fahd Islamic School, New South Wales

- Minaret College, Victoria

- Noor Al Houda Islamic College, New South Wales

- Rissalah College, New South Wales

- Werribee Islamic College, Victoria

- Sule College, New South Wales

- Isik College, Victoria

See also

References

- ^ state.gov; CIA Factbook

- ^ Reuters - Australian town rejects Muslim school

- ^ Macknight, Charles Campbell.(1976) The voyage to Marege’ : Macassan trepangers in Northern Australia Carlton, Vic. : Melbourne University Press. ISBN 0522840884

- ^ Cooke, Michael (1987) Makassar & north east Arnhem Land : missing links & living bridges Batchelor, N.T. Batchelor College. ISBN 0724517790 Includes appendix: Excerpts from Yolnu-Matha dictionary, Macassan loanwords project (29–30 May 1986), by R. David Paul Zorc.

- ^ Jones, Philip G and Kenny, Anna (2007) Australia’s Muslim cameleers : pioneers of the inland, 1860s-1930s Kent Town, S. Aust. : Wakefield Press. ISBN 9781862547780

- ^ Arthur Clark (January/February 1988). "Camels Down Under". Saudi Aramco World. http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/198801/camels.down.under.htm. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- ^ Dr Nahid Kabir (7 September 2007). "A History of Muslims in Australia". The (Dhaka) Daily Star, Bangladesh. http://www.thedailystar.net/magazine/2007/09/01/perspective.htm. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- ^ Bowen, James; Bowen, Margarita (2002). The Great Barrier Reef: History, Science, Heritage. Cambridge University Press. p. 301. ISBN 0521824303. http://books.google.com/?id=ywV16n6mOUUC&pg=PA301&lpg=PA301&dq=%22stanley+bruce%22. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ^ "Policy Launch Speech: Stanley Bruce, Prime Minister" (PDF). Melbourne: The Age. 26 October 1925. p. 11. Archived from the original on 2006. http://soapbox.unimelb.edu.au/media/Transcripts/Speech_PolicyLaunch/1925_PolicyLaunchSpeech_NAT_T.pdf. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ^ a b c d http://www.pupr.edu/hkettani/papers/HICAH2010.pdf Proceedings of the 8th Hawaii International Conference on Arts and Humanities, Honolulu, Hawaii, Januaiy 2010, 2010 World Muslim Population, Houssain Kettani, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Computer Science, Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico, USA p.46

- ^ "Muslim Journeys - Arrivals - Lebanese". National Archives of Australia. 2001. http://uncommonlives.naa.gov.au/contents.asp?cID=99. Retrieved 2009-02-16.[dead link]

- ^ "The Special Case: the Ahmadiyya Muslims". Global Politician. http://www.globalpolitician.com/22785-islam. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- ^ "Social integration of Muslim Settlers in Cobram" (PDF). Centre for Muslim Minorities and Islam Policy Studies - Monash University. 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-09-02. http://web.archive.org/web/20070902143324/http://arts.monash.edu.au/politics/cmmips/publications/cobram-integration.pdf. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ Islam in indigenous Australia

- ^ Phil Mercer (31 March 2003). "Aborigines turn to Islam". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/2902315.stm. Retrieved 2006-11-19.

- ^ Aboriginal Muslims Find Strength In Islam :: MuslimVillage.net

- ^ Kathy Marks, The Independent Militant Aborigines embrace Islam to seek empowerment. 28 February 2003. Retrieved 2007-02-01.

- ^ HREOC FACT SHEET : Australian Muslims

- ^ a b c d "3416.0 - Perspectives on Migrants, 2007: Birthplace and Religion". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2008-02-25. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Latestproducts/3416.0Main%20Features22007?opendocument&tabname=Summary&prodno=3416.0&issue=2007&num=&view=. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ "Cultural diversity". 1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2008. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2008-02-07. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/7d12b0f6763c78caca257061001cc588/636F496B2B943F12CA2573D200109DA9?opendocument. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ^ a b c Muslim Australians - E-Brief

- ^ Muslims' youth summit plan

- ^ Sydney's Muslims fear revenge attacks

- ^ Henderson, Gerard (15 January 2007). "How Australia confronts militant Islam". The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/columnists/guest_contributors/article1292968.ece.

- ^ Dailymail - Outrage as Muslim cleric likens women to 'uncovered meat

- ^ BBC News - Excerpts of al-Hilali's speech

- ^ BBC News - Australia fury at cleric comments

- ^ Muslim leader's rape comments under fire

- ^ Muslims must speak out, or be condemned for their silence

- ^ We're not fresh meat: Muslim women hit back

- ^ Islamic cleric Samir Abu Hamza 'must back down', www.news.com.au. Retrieved on 25 January 2008

- ^ Muslim Holy Man Says Aussies Love Gambling, Hookers, and Beer, Online Casino Advisory. Retrieved on 25 January 2008

- ^ Perth Islamic group slams Victorian cleric's violent views, www.watoday.com.au. Retrieved on 25 January 2008

- ^ Hughes, Gary. Cleric told to apologise for video remarks on rape, The Australian. Retrieved on 25 January 2008

- ^ Heed the PM's call for women's rights

- ^ "National consultations on eliminating prejudice against Arab and Muslim Australians". HREOC. 16 June 2004. http://www.hreoc.gov.au/racial_discrimination/isma/report/chap2.html. Retrieved 2008-07-09.

- ^ Australia

Further reading

- Cleland, Bilal. The Muslims in Australia: A Brief History. Melbourne: Islamic Council of Victoria, 2002.

- Deen, Hanifa. Muslim Journeys. Online: National Archives of Australia, 2007.

- Kabir, Nahid. Muslims in Australia: Immigration, Race Relations and Cultural History. London: Kegan Paul, 2004.

- Kabir, Nahid (July 2006). "Muslims in a 'White Australia': Colour or Religion?". Immigrants and Minorities 24 (2): 193–223. doi:10.1080/02619280600863671.

- Saeed, Abdullah. Islam in Australia. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2003.

- Saeed, Abdullah and Shahram Akbarzadeh, eds. Muslim Communities in Australia. Sydney: UNSW Press, 2001.

- Stevens, Christine. Tin Mosques and Ghantowns.

External links

- Australian Federation of Islamic Councils

- Muslim Journeys – historical community biography produced by the National Archives of Australia

- Australian Multicultural Foundation

- Australian Bureau of Statistics 2001 Census Dictionary - Religion category

Religion in Australia Christianity Roman Catholic · Anglican · Uniting Church · Presbyterian · Baptist · Lutheran · Coptic Orthodox · moreOther Religions Related Topics Islam in Oceania Sovereign states - Australia

- East Timor (Timor-Leste)

- Fiji

- Indonesia

- Kiribati

- Marshall Islands

- Federated States of Micronesia

- Nauru

- New Zealand

- Palau

- Papua New Guinea

- Samoa

- Solomon Islands

- Tonga

- Tuvalu

- Vanuatu

Dependencies and

other territories- American Samoa

- Christmas Island

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Cook Islands

- Easter Island

- French Polynesia

- Guam

- Hawaii

- New Caledonia

- Niue

- Norfolk Island

- Northern Mariana Islands

- Pitcairn Islands

- Tokelau

- Wallis and Futuna

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.