- Franco-Mongol alliance

-

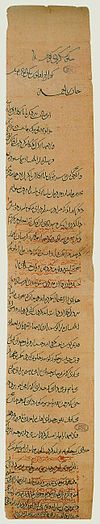

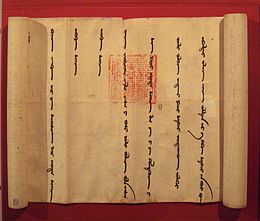

1305 letter (a roll measuring 302 by 50 centimetres (9.91 by 1.6 ft)) from the Ilkhan Mongol Öljaitü to King Philip IV of France, suggesting military collaboration.

1305 letter (a roll measuring 302 by 50 centimetres (9.91 by 1.6 ft)) from the Ilkhan Mongol Öljaitü to King Philip IV of France, suggesting military collaboration.

Franco-Mongol relations were established in the 13th century, as attempts were made towards forming a Franco-Mongol alliance between the Christian Crusaders and the Mongol Empire against various Muslim empires. Such an alliance would have seemed a logical choice: the Mongols were sympathetic to Christianity as they had many influential Nestorian Christians in the Mongol court. The Franks (Europeans)[1] were open to the idea of assistance coming from the East, due to the long-running legend of a mythical Prester John, an Eastern king in a magical kingdom who many believed would arrive someday to help with the Crusades in the Holy Land.[2][3] They also shared a common enemy in the Muslim empires. However, despite generations of messages, gifts, and emissaries, the often-proposed alliance was never achieved.[2][4]

Contact between the Europeans and Mongols began around 1220, through infrequent messages from the Papacy or European monarchs, to Mongol leaders such as the Great Khan, and later to the Ilkhans in Mongol-conquered Iran. The pattern of communications tended to repeat, with the Europeans asking the Mongols to convert to Western Christianity, and the Mongols simply responding with demands for submission and tribute. The Mongols had already conquered other Christian nations in their advance across Asia, including the Kingdoms of Georgia and Cilician Armenia. The Mongols then destroyed both the Muslim Abbasid and Ayyubid dynasties, and for the next few generations fought against the remaining Islamic power in the region, that of the Egyptian Mamluks. Hethum I, King of Armenia, strongly encouraged European monarchs to follow his example and submit to Mongol authority, but was only able to persuade his son-in-law, Prince Bohemond VI of the Crusader state of Antioch, who submitted in 1260. The Crusaders of Acre though, saw the Mongols as a greater threat than the Muslims, and allowed the Egyptians to advance unhampered through Crusader territory to engage and defeat the Mongols at the pivotal Battle of Ain Jalut (1260).[5]

European attitudes began changing in the mid-1260s, from perceiving the Mongols as enemies to be feared, to potential allies against the Muslims. The Mongols capitalized on this, promising a re-conquered Jerusalem to the Europeans, in return for cooperation. Attempts towards an alliance continued through negotiations with multiple leaders of the Mongol Ilkhanate in Iran, from its founder Hulagu through his descendants Abaqa, Arghun, Ghazan, and Öljaitü, but without success. The Mongols invaded Syria several times between 1281 and 1312, sometimes in attempts at joint operations with the Europeans; however, there were considerable logistical difficulties involved, which usually resulted in the forces arriving months apart, and being unable to satisfactorily combine their activities.[6]

The Mongol Empire eventually dissolved into civil war, and the Egyptian Mamluks successfully recaptured all of Palestine and Syria from the Crusaders. After the Fall of Acre in 1291, the remaining Crusaders retreated to the island of Cyprus. A final attempt was made to establish a bridgehead at the small island of Ruad off the coast of Tortosa, again in an attempt to coordinate military action with the Mongols. The plan for collaboration failed, the Egyptians later besieged the island, and with the Fall of Ruad in 1302 or 1303, the Crusaders lost their last foothold in the Holy Land.[7]

Modern historians debate whether an alliance between the Europeans and Mongols, if it had been successful, would have even been effective in shifting the balance of power in the region, and/or whether it would have been a wise choice on the part of the Europeans.[8] Traditionally, the Mongols tended to see outside parties as either subjects or enemies, with little room in the middle for a concept such as an ally.[9]

Early contacts (1209–1244)

See also: Christianity among the Mongols and Mongol invasion of Europe Expansion of the Mongol Empire

Expansion of the Mongol Empire

Among Europeans, there had long been rumors and expectations that a great Christian ally would come from the East. These rumors circulated as early as the First Crusade, and usually surged in popularity after the loss of a battle by the Crusaders. A legend developed about a figure known as Prester John, who lived in far off India, Central Asia, or perhaps even Ethiopia. This legend fed upon itself, and some individuals who came from the East were greeted with the expectations that they might be the long-awaited Christian heroes. In 1210, news reached the West of the battles of the Mongol Kuchlug, leader of the largely Christian tribe of the Naimans. Kuchlug's forces had been battling the powerful Khwarezmian Empire, whose leader was Muhammad II of Khwarezm. Rumors circulated in Europe that Kuchlug was the mythical Prester John, and was again battling the Muslims in the East.[10]

During the Fifth Crusade, as the Christians were unsuccessfully laying siege to the Egyptian city of Damietta, the legends of Prester John again conflated with the reality of Genghis Khan's rapidly expanding Empire.[10] Mongol raiding parties were beginning to invade the eastern Islamic world, in Transoxania and Persia in 1219–1221.[11] Rumors circulated among the Crusaders that a "Christian king of the Indies", a King David who was either Prester John or one of his descendants, had been attacking Muslims in the East, and was on his way to help the Christians in their Crusades.[12] In a letter dated June 20, 1221, Pope Honorius III even commented about "forces coming from the Far East to rescue the Holy Land".[13]

Genghis Khan died in 1227, and his empire was split up by his descendants into four sections, or Khanates, which degenerated into civil war. The northwestern Kipchak Khanate, known as the Golden Horde, expanded towards Europe, primarily via Hungary and Poland, while simultaneously opposing the rule of their cousins back at the Mongol capital. The southwestern section, known as the Ilkhanate, was under the leadership of Genghis Khan's grandson Hulagu. He continued to support his brother the Great Khan, and was therefore at war with the Golden Horde, while simultaneously continuing an advance towards Persia and the Holy Land.[14]

Papal overtures (1245–1248)

The first official communications between Europe and the Mongol Empire occurred between Pope Innocent IV (fl. 1243–1254) and the Great Khans, via letters and envoys which were sent overland and could take years to arrive. The communications initiated what was to be a regular pattern in Christian–Mongol communications: the Europeans would ask for the Mongols to convert to Christianity, but the Mongols would simply respond with demands for submission.[9][15]

The Mongol invasion of Europe subsided in 1242, in part because of the death of the Great Khan Ögedei, successor of Genghis Khan. When one Great Khan died, Mongols from all parts of the Empire were recalled to the capital, to decide who should be the next Great Khan.[16] However, the Mongols' relentless march westward had displaced the Khawarizmi Turks, who themselves moved west, eventually allying with the Ayyubid Muslims in Egypt.[17] Along the way, the Turks took Jerusalem from the Christians in 1244, which prompted Christian kings to prepare for a new Crusade (the Seventh Crusade), declared by Pope Innocent IV at the First Council of Lyon in June 1245.[18][19]

The loss of Jerusalem again caused some Europeans to look to the Mongols as potential allies of Christendom, if the Mongols could be converted to Western Christianity.[4] In March 1245, Pope Innocent IV issued multiple Papal bulls, some of which were sent with an envoy, the Franciscan John of Plano Carpini, to the "Emperor of the Tartars". In Cum non solum, Pope Innocent asked the Mongol ruler to become a Christian and to stop killing Christians. He also expressed a desire for peace.[20] However, the new Mongol Great Khan Guyuk, installed at Karakorum in 1246, replied only with a demand for the submission of the Pope, and a visit from the rulers of the West in homage to Mongol power:[21]

"You should say with a sincere heart: 'I will submit and serve you.' Thou thyself, at the head of all the Princes, come at once to serve and wait upon us! At that time I shall recognize your submission. If you do not observe God's command, and if you ignore my command, I shall know you as my enemy."A second mission sent in 1245 by Pope Innocent was led by the Dominican Ascelin of Lombardia. The mission met with the Mongol commander Baiju near the Caspian Sea in 1247. Baiju, who had plans to capture Baghdad, welcomed the possibility of an alliance and sent a message back via his envoys Aïbeg and Serkis. They accompanied Innocent's embassy back to Rome, and stayed for about a year, meeting with Innocent in 1248. The Pope replied to the Mongols with his own letter Viam agnoscere veritatis, in which he appealed to the Mongols to "cease their menaces".[23]

Christian vassals

See also: Mongol invasions of Georgia and ArmeniaAs the Mongols of the Ilkhanate continued to move towards the Holy Land, city after city fell to the Mongols. The typical Mongol pattern was to give a region one chance to surrender. If the target acquiesced, the Mongols absorbed the populace and warriors into their own Mongol army, which they would then use to further expand the empire. If a community did not surrender, the Mongols forcefully took the settlement or settlements and slaughtered everyone they found.[24] Faced with the option of subjugation or facing the nearby Mongol horde, many communities chose the former, including some Christian realms.[25]

Among the Christian states in the Levant, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (in blue) and the northern Frank realms of the Principality of Antioch and the County of Tripoli (green) were the most regular allies/subjects of the Mongols, and were required to supply troops to participate in Mongol campaigns.

Among the Christian states in the Levant, the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia (in blue) and the northern Frank realms of the Principality of Antioch and the County of Tripoli (green) were the most regular allies/subjects of the Mongols, and were required to supply troops to participate in Mongol campaigns.

Christian Georgia was repeatedly attacked starting in 1220, and in 1243 Queen Rusudan formally submitted to the Mongols, turning Georgia into a vassal state which then became a regular ally in the Mongol military conquests.[26] Hethum I, King of Armenia submitted in 1247, and became the main conduit of diplomacy between the Mongols and the Europeans, as he strongly encouraged the European monarchs to follow his own example.[27][28] He sent his brother Sempad to the Mongol court in Karakorum, and Sempad's positive letters about the Mongols were influential in European circles.[29] However, the only monarch who followed Hethum's advice was his son-in-law, Prince Bohemond VI of Antioch.[30][31]

Antioch

The Principality of Antioch was one of the earliest Crusader states, having been formed in 1098 as a result of the First Crusade. At the time of the Mongol advance, it was under the rule of Bohemond VI. Under the influence of his father-in-law, King Hethum I of Cilican Armenia, Bohemond too submitted Antioch to Hulagu in 1260.[32] A Mongol representative and a Mongol garrison were stationed in the capital city of Antioch, where they remained until the Principality was destroyed by the Mamluks in 1268.[33][34] Bohemond was also required by the Mongols to accept the restoration of a Greek Orthodox patriarch, Euthymius, as a way of strengthening ties between the Mongols and the Byzantines. In return for this loyalty, Hulagu awarded Bohemond all the Antiochene territories which had been lost to the Muslims in 1243. But for his relations with the Mongols, Bohemond was also temporarily excommunicated by Jacques Pantaléon, the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem, though this was lifted in 1263.[35]

In 1262, the Mamluk leader Baibars threatened Antioch for its association with the Mongols. Baibars attempted an attack, but Antioch was saved by Mongol intervention.[36] In later years however the Mongols were not able to offer as much support. In 1264–1265 the Mongols were only able to attack the frontier fort of al-Bira, and in 1268 Baibars completely overran the area, and the 170-year-old principality was no more.[37][38] In 1271, Baibars sent a letter to Bohemond threatening him with total annihilation and taunting him for his alliance with the Mongols:

"Our yellow flags have repelled your red flags, and the sound of the bells has been replaced by the call: "Allâh Akbar!" (...) Warn your walls and your churches that soon our siege machinery will deal with them, your knights that soon our swords will invite themselves in their homes (...) We will see then what use will be your alliance with Abagha."—Letter from Baibars to Bohemond VI, 1271[39]Bohemond was left with no estates except the County of Tripoli, which was itself to fall to the Mamluks in 1289.[40]

Saint Louis and the Mongols

Statue of Louis IX at the Sainte Chapelle, Paris.

Statue of Louis IX at the Sainte Chapelle, Paris. Main article: Seventh Crusade

Main article: Seventh CrusadeLouis IX of France had engaged in communications with the Mongols since his first Crusade, when he was met on December 20, 1248 in Cyprus by two Mongol envoys, Nestorians from Mosul named David and Marc, who brought a letter from the Mongol commander in Persia, Eljigidei.[41] The letter communicated a more conciliatory tone than previous Mongol demands for submission. Eljigidei's envoys suggested that King Louis should land in Egypt, while Eljigidei attacked Baghdad, as a way of preventing the Saracens of Egypt and those of Syria from joining forces.[42] Louis responded by sending the emissary Andrew of Longjumeau to the Great Khan Güyük. However, Güyük died, from drink, before the emissary arrived at his court. Güyük's widow Oghul Qaimish simply gave the emissary a gift and a condescending letter to take back to King Louis, instructing him to continue sending tributes each year.[43][44][45]

Louis IX's Crusade against Egypt did not go well. Despite initial success in capturing Damietta, he then lost his entire army at the Battle of Al Mansurah and he was himself captured by the Egyptians. His release was eventually negotiated, in return for a ransom (some of which was a loan from the Templars), and the surrender of the city of Damietta.[46]

A few years later, in 1252, Louis tried unsuccessfully to ally with the Egyptians, and then in 1253 he tried to seek allies from among both the Ismailian Assassins and again from the Mongols.[47] When he saw a letter from Hethum's brother, the Armenian noble Sempad, which spoke well of the Mongols, Louis dispatched the Franciscan William of Rubruck to the Mongol court. However, the Mongol leader Möngke replied only with a letter via William in 1254, asking for the King's submission to Mongol authority.[48]

King Louis attempted a second Crusade (the Eighth Crusade) in 1270. The Mongol Ilkhanate leader Abaqa wrote to Louis IX offering military support as soon as the Crusaders landed in Palestine, but Louis instead went to Tunis in modern Tunisia. His intention was evidently to first conquer Tunis, and then to move his troops along the coast to reach Alexandria in Egypt.[49] The French historians Alain Demurger and Jean Richard suggest that this Crusade may still have been an attempt at coordination with the Mongols, in that Louis may have attacked Tunis instead of Syria following a message from Abaqa that he would not be able to commit his forces in 1270, and asking to postpone the campaign to 1271.[50][51]

Envoys from the Byzantine emperor, the Armenians and the Mongols of Abaqa were present at Tunis, but events put a stop to plans for a continued Crusade, as Louis died there of illness.[51] According to legend, his last words were "Jerusalem".[52]

Relations with the Ilkhanate

Hulagu (1256–1265)

Main article: Hulagu KhanHulagu, a grandson of Genghis Khan, was an avowed shamanist, but was nevertheless very tolerant of Christianity. His mother Sorghaghtani Beki, his favorite wife Doquz Khatun, and several of his closest collaborators were Nestorian Christians. One of his most important generals, Kitbuqa, was a Nestorian Christian of the Naiman tribe.[4]

Military collaboration between the Mongols and their Christian vassals became substantial in 1258–1260. Hulagu's army, with the forces of his Christian subjects Bohemond VI of Antioch, Hethum I of Armenia, and the Christian Georgians, effectively destroyed two of the most powerful Muslim dynasties of the era: both that of the Abbasids in Baghdad, and the Ayyubids in Syria.[14]

Fall of Baghdad (1258)

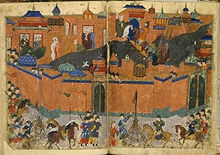

Main article: Siege of Baghdad (1258)The Abbasid Caliphate, founded by one of the relatives of Muhammad in the 8th century, had ruled northeastern Africa, Arabia, and the Near East. Their seat of power for 500 years was Baghdad, a city considered to be the jewel of Islam and one of the largest and most powerful cities in the world. But under attack from the Mongols, the city fell on February 15, 1258, an event often considered as the single most catastrophic event in the history of Islam. The Christian Georgians had been the first to breach the walls, and as described by historian Steven Runciman, "were particularly fiercest in their destruction".[53] When Hulagu conquered the city, the Mongols demolished buildings, burned entire neighborhoods, and massacred nearly 80,000 men, women, and children. But at the intervention of Hulagu's Nestorian Christian wife Doquz Khatun, the Christian inhabitants were spared.[54]

Hulagu and Queen Doquz Qatun depicted as the new "Constantine and Helen", in a Syriac Bible.[55][56]

Hulagu and Queen Doquz Qatun depicted as the new "Constantine and Helen", in a Syriac Bible.[55][56]

For Asiatic Christians, the fall of Baghdad was cause for celebration.[57][58][59] Hulagu and his Christian queen Doquz came to be considered as God's agents against the enemies of Christianity.[58] The Mongol royal couple was described as "another Constantine, another Helen" for the Armenian Church, by the Armenian historian Kyrakos of Ganja. The couple was even represented as Constantine and Helena in a painting.[55][57][60] Bar Hebraeus, a bishop of the Syriac Orthodox Church, also referred to them as a Constantine and Helena, and wrote of Hulagu that nothing could compare to the "king of kings" in "wisdom, high-mindedness, and splendid deeds".[57]

Invasion of Syria (1260)

After Baghdad, in 1260 the Mongols with their Christian subjects conquered Muslim Syria, domain of the Ayyubid dynasty. They took together the city of Aleppo in January, and in March, the Mongols with the Armenians and the Franks of Antioch took Damascus, under the Christian Mongol general Kitbuqa.[14][33]

With both the Abbasid and Ayyubid dynasties destroyed, the Near East, as described by historian Steven Runciman, "was never again to dominate civilization."[61] The last Ayyubid king An-Nasir Yusuf died shortly thereafter, and with the Islamic power centers of Baghdad and Damascus gone, the center of Islamic power transferred to the Egyptian Mamluks in Cairo.[14][62]

However, before the Mongols could continue their advance towards Egypt, they needed to withdraw because of other internal matters in the Mongol Empire. Hulagu departed with the bulk of his forces, leaving a small force under Kitbuqa to occupy the conquered territory. Mongol raiding parties were sent southwards into Palestine towards Egypt, with small Mongol garrisons of about 1,000 established in Gaza.[33][63][64]

Incidents

See also: Mongol raids into PalestineWith Mongol territory now bordering the Franks, a few incidents occurred, one of them leading to an incident in Sidon. Julian de Grenier, Lord of Sidon and Beaufort, described by his contemporaries as irresponsible and light-headed, took the opportunity to raid and plunder the area of the Beqaa Valley in Mongol territory. When the Mongol general Kitbuqa sent his nephew with a small force to obtain redress, they were ambushed and killed by Julian. Kitbuqa responded forcefully by raiding the city of Sidon. These events generated a significant level of distrust between the Mongols and the Crusader forces, whose own center of power was now in the coastal city of Acre.[65]

The incidents raised the ire of the Mamluk leader Baibars, who declared that the treaty that had been signed between the Crusaders and the Mamluks in 1240 had been invalidated when Christian forces assisted the Mongols to capture Damascus. Baibars demanded the evacuation of Saphet and Beaufort, and when the Christians balked, Baibars used that as his excuse to violate the pre-existing truce, and start launching new attacks on such settlements as Nazareth, Mount Tabor, and Bethlehem.[37]

Battle of Ain Jalut

Main article: Battle of Ain JalutPope Urban IV (1195–1264), originally warned of the Mongol threat when he was James Pantaleon, Patriarch of Jerusalem. As Pope, he engaged in communications with the Mongols in 1263.

The Franks of Antioch aside, other Christians worked against the Mongols. Jacques Pantaléon, the Patriarch of Jerusalem, saw the Mongols as a clear threat, and had written to the Pope to warn him about them in 1256.[66] The Franks did, however, send the Dominican David of Ashby to the court of Hulagu in 1260.[48]

That same year, the Franks of Acre maintained a position of cautious neutrality between the Mongols and the Mamluks.[5] Though traditional enemies of the Mamluks, the Franks acknowledged that the Mongols were a greater threat, and therefore entered into a passive truce with the Egyptians. The Barons of Acre allowed the Mamluk forces to move northward through Christian territory unhampered to engage the Mongols, in exchange for an agreement to purchase captured Mongol horses at a low price.[67][68]

The truce allowed the Mamluks to proceed north with their army, camp and re-supply near Acre, and engage the Mongols at the pivotal Battle of Ain Jalut on September 3, 1260. The Mongol forces were already depleted, as the bulk of the Mongol army had returned with Hulagu to the Mongol capital to engage in discussions about who should be the next Great Khan. Hulagu had left a smaller force to continue the Mongol advance and occupy Syria and Palestine, under his general Kitbuqa. With the passive assistance of the Franks, the Mamluks were able to engage Kitbuqa's force at Ain Jalut, and achieve a decisive and historic victory over the Mongols. It was the first major battle that the Mongols lost, and set the western border for what had seemed an unstoppable expansion of the Mongol Empire.[5]

Following Ain Jalut, the remainder of the Mongol army retreated to Cilician Armenia under the commander Ilka, where the Mongols were received and re-equipped by Hethum I.[37]

Papal communications

In the 1260s, a change occurred in the European perception of the Mongols, and they became regarded less as enemies, and more as potential allies in the fight against the Muslims.[69]

As recently as 1259, Pope Alexander IV had been encouraging a new Crusade against the Mongols, and had been extremely disappointed in hearing that the monarchs of Antioch and Cilician Armenia had submitted to Mongol overlordship. Alexander had put the monarchs' cases on the agenda of his upcoming council, but died in 1261 just months before the Council could be convened, and before the new Crusade could be launched.[70] For a new Pope, the choice fell to Pantaléon, the same Patriarch of Jerusalem who had earlier been warning of the Mongol threat. He took the name Pope Urban IV, and tried to raise money for a new crusade.[71]

On April 10, 1262, the Mongol leader Hulagu sent through John the Hungarian a new letter to the French king Louis IX, again offering an alliance.[72] The letter explained that previously, the Mongols had been under the impression that the Pope was the leader of the Christians, but now they realized that the true power rested with the French monarchy. The letter mentioned Hulagu's intention to capture Jerusalem for the benefit of the Pope, and asked for Louis to send a fleet against Egypt. Hulagu promised the restoration of Jerusalem to the Christians, but also still insisted on Mongol sovereignty, in the Mongols' quest for conquering the world. It is unclear whether or not King Louis actually received the letter, but at some point it was transmitted to Pope Urban, who answered in a similar way as his predecessors. In his papal bull Exultavit cor nostrum, Urban congratulated Hulagu on his expression of goodwill towards the Christian faith, and encouraged him to convert to Christianity.[73]

Historians dispute the exact meaning of Urban's actions. The mainstream view, such as that espoused by British historian Peter Jackson, states that Urban still regarded the Mongols as enemies at this time, though the perception began changing a few years later, during the pontificate of Pope Clement IV, when the Mongols were seen more as potential allies. However, the French historian Jean Richard argues that Urban's act signaled a turning point in Mongol-European relations as early as 1263, after which the Mongols were considered as actual allies. Richard also argues that it was in response to this forming coalition between the Franks, Ilkhanid Mongols and Byzantines, that the Mongols of the Golden Horde allied with the Muslim Mamluks in return.[74][75] However, the mainstream view of historians is that though there were many attempts at forming an alliance, the attempts proved unsuccessful.[2]

Abaqa (1265–1282)

Main article: Abaqa KhanHulagu died in 1265, and was succeeded by Abaqa (1234–1282), who further pursued Western cooperation. Though a Buddhist, upon his succession he received the hand of Maria Palaiologina, an Orthodox Christian and the illegitimate daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos, in marriage.[76]

Abaqa corresponded with Pope Clement IV through 1267 and 1268, sending envoys to both Clement and King James I of Aragon. In a 1268 message to Clement, Abaqa promised to send troops to aid the Christians. It is unclear if this was what led to James's unsuccessful expedition to Acre in 1269.[12] James initiated a small crusade, but a storm descended on his fleet as they attempted their crossing, forcing most of the ships to turn back. The crusade was ultimately handled by James's two sons Fernando Sanchez and Pedro Fernandez, who arrived in Acre in December 1269.[77] Abaqa, despite his earlier promises of assistance, was in the process of facing another threat, an invasion in Khorasan by Mongols from Turkestan, and so could only commit a small force for the Holy Land, which did little but brandish the threat of an invasion along the Syrian frontier in October 1269. He raided as far as Harim and Afamiyaa in October, but retreated as soon as Baibars' forces advanced.[32]

Edward I's Crusade (1269–1274)

In 1269, the English Prince Edward (the future Edward I), inspired by tales of his great-uncle, Richard the Lionheart, and the second Crusade of the French King Louis, started on a Crusade of his own, the Ninth Crusade.[78] The number of knights and retainers that accompanied Edward on the crusade was quite small, possibly around 230 knights, with a total complement of approximately 1,000 people, transported in a flotilla of 13 ships.[40][79] Edward understood the value of an alliance with the Mongols, and upon his arrival in Acre on May 9, 1271, he immediately sent an embassy to the Mongol ruler Abaqa, requesting assistance.[80] Abaqa answered positively to Edward's request, asking him to coordinate his activities with his general Samagar, whom he sent on an offensive against the Mamluks with 10,000 Mongols to join Edward's army.[32][81] But Edward was able only to engage in some fairly ineffectual raids that did not actually achieve success in gaining new territory.[78] For example, when he engaged in a raid into the Plain of Sharon, he proved unable to even take the small Mamluk fortress of Qaqun.[32] However, Edward's military operations, limited though they were, were still of assistance in persuading the Mamluk leader Baibars to agree to a 10-year truce between the city of Acre and the Mamluks, signed in 1272.[82] Edward's efforts were described by historian Reuven Amitai as "the nearest thing to real Mongol-Frankish military coordination that was ever to be achieved, by Edward or any other Frankish leader."[83]

Council of Lyon (1274)

In 1274, Pope Gregory X convened the Second Council of Lyon. Abaqa sent a delegation of 13 to 16 Mongols to the Council, which created a great stir, particularly when three of their members underwent a public baptism.[85] Abaqa's Latin secretary Rychaldus delivered a report to the Council which outlined previous European-Ilkhanid relations under Abaqa's father, Hulagu, affirming that after Hulagu had welcomed Christian ambassadors to his court, he had agreed to exempt Latin Christians from taxes and charges, in exchange for their prayers for the Khan. According to Rychaldus, Hulagu had also prohibited the molestation of Frank establishments, and had committed to return Jerusalem to the Franks.[86] Rychaldus assured the assembly that even after Hulagu's death, his son Abaqa was still determined to drive the Mamluks from Syria.[32]

At the Council, Pope Gregory promulgated a new Crusade, in liaison with the Mongols.[84] The Pope put in place a vast program to launch the Crusade, which was written down in his "Constitutions for the zeal of the faith". The text put forward four main decisions to accomplish the Crusade: the imposition of a new tax during three years, the interdiction of trade with the Sarazins, the supply of ships by the Italian maritime Republics, and the alliance of the West with both Byzantium and the Mongol Il-Khan Abaqa.[87]

Following these exchanges, Abaqa sent another embassy, led by the Georgian Vassali brothers, to further notify Western leaders of military preparations. Gregory answered that his legates would accompany the Crusade, and that they would be in charge of coordinating military operations with the Il-Khan.[88]

However, the papal plans were not supported by the other European monarchs, who had lost enthusiasm for the Crusades. Only one western monarch attended the Council, the elderly James I of Aragon, who could only offer a small force. There was fundraising for a new Crusade, and plans were made but never followed through. The projects essentially came to a halt with the death of Pope Gregory on January 10, 1276, and the money which had been raised to finance the expedition was instead distributed in Italy.[40]

Invasion of Syria (1280–1281)

See also: Mongol invasions of SyriaWithout support from the Europeans, some Franks of Syria, particularly the Knights Hospitaller of the fortress of Marqab, and to some extent the Franks of Cyprus and Antioch, attempted to join in combined operations with the Mongols in 1280–1281.[88][89]

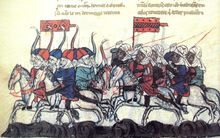

Defeat of the Mongols (left) at the 1281 Battle of Homs.

Following the death of Baibars in 1277, and the ensuing disorganization of the Muslim realm, conditions were ripe for a new action in the Holy Land.[88] The Mongols seized the opportunity and organized a new invasion of Syria. In September 1280, the Mongols occupied Bagras and Darbsak, and took Aleppo on October 20. Abaqa sent envoys to Edward I of England, the Franks of Acre, King Hugh of Cyprus, and Bohemond VII of Tripoli (son of Bohemond VI), requesting their support for the campaign.[90] But the Patriarch's Vicar indicated that the city of Acre was suffering from hunger, and that the king of Jerusalem was already embroiled in another war.[88]

Local Knights Hospitaller from Marqab (in the area which had previously been Antioch/Tripoli) were able to make raids into the Buqaia, as far as the Mamluk-held Krak des Chevaliers in 1280 and 1281. Hugh and Bohemond mobilized their armies, but the main forces of the Franks and the Mongols were prevented from joining by the new Egyptian Sultan Qalawun, who advanced north from Egypt in March 1281, and positioned his own army between them.[88][89]

Qalawun further divided the potential allies by renewing a truce with the Barons of Acre on May 3, 1281, extending it for another ten years and ten months (a truce he would later breach).[90] He also renewed a second 10-year truce with Bohemond VII of Tripoli on July 16, 1281, and affirmed pilgrim access to Jerusalem.[88]

In September 1281 the Mongols returned, with 50,000 of their own troops, plus 30,000 others including Armenians under Leo III, Georgians, and 200 Knights Hospitaller from Marqab, who sent a contingent even though the Franks of Acre had agreed a truce with the Mamluks.[90][91][92] The Mongols and their auxiliary troops fought against the Mamluks at the Second Battle of Hims on 30 October 1281, but the encounter was indecisive, with the Sultan suffering heavy losses.[89][91] In retaliation, Qalawun later besieged and captured the Hospitaller fortress of Marqab in 1285.[91]

Arghun (1284–1291)

Main article: ArghunAbaqa died in 1282 and was briefly replaced by his brother Tekuder, a converted Muslim. Tekuder reversed Abaqa's policy of seeking an alliance with the Christian Europeans, offering instead an alliance to the Mamluk Sultan Qalawun, who continued his own advance, capturing the Hospitaller fortress of Margat in 1285, Lattakia in 1287, and the County of Tripoli in 1289.[40][88]

1289 letter of Arghun to Philip IV of France, in the Mongolian script, with detail of the introduction. The letter was remitted to the French king by Buscarel of Gisolfe. 182 by 25 centimetres (72 × 9.8 in). French National Archives.[93]

1289 letter of Arghun to Philip IV of France, in the Mongolian script, with detail of the introduction. The letter was remitted to the French king by Buscarel of Gisolfe. 182 by 25 centimetres (72 × 9.8 in). French National Archives.[93]

However, Tekuder's pro-Muslim stance was not popular, and in 1284, Abaqa's Buddhist son Arghun, with the support of the Great Khan Kublai, led a revolt and had Tekuder executed. Arghun then revived the idea of an alliance with the West, and sent multiple envoys to Europe.[94]

The first of Arghun's embassies was led by Isa Kelemechi, a Nestorian Syrian scientist who had been head of Kublai Khan's astrological observatory in China. Kelemechi met with Pope Honorius IV in 1285, offering to "remove" the Saracens (Muslims) and divide "the land of Sham, namely Egypt" with the Franks.[94][95] The second embassy, and probably the most famous, was that of the elderly cleric Rabban Bar Sauma, who had been visiting the Ilkhanate during a remarkable pilgrimage from China to Jerusalem.[94]

Through Bar Sauma and other later envoys, such as Buscarello de Ghizolfi, Arghun promised the European leaders that if Jerusalem were conquered, he would have himself baptised and would return Jerusalem to the Christians.[96] Bar Sauma was greeted warmly by the European monarchs;[94] however, Western Europe was no longer as interested in the Crusades, and the mission to form an alliance was ultimately fruitless.[97][98] England did respond by sending a representative, Geoffrey of Langley, who had been a member of Edward I's Crusade 20 years earlier, and was sent to the Mongol court as an ambassador in 1291.[99]

Genoese shipmakers

Another link between Europe and the Mongols was attempted in 1290, when the Genoese endeavored to assist the Mongols with naval operations. The plan was to construct and man two galleys to attack Mamluk ships in the Red Sea, and operate a blockade of Egypt's trade with India.[100][101] As the Genoese were traditional supporters of the Mamluks, this was a major shift in policy, apparently motivated by the attack of the Egyptian Sultan Qalawun on the Cilician Armenians in 1285.[102]

To build and man the fleet, a squadron of 800 Genoese carpenters, sailors, and crossbowmen went to Baghdad, working on the Tigris.[100][101] However, due to a feud between the Guelfs and Ghibellines, the Genoese soon degenerated into internal bickering, and killed each other in Basra, putting an end to the project.[100][101] Genoa finally cancelled the agreement and signed a new treaty with the Mamluks instead.[102]

All these attempts to mount a combined offensive between the Franks and Mongols were too little and too late. On March 1291, the city of Acre was conquered by the Egyptian Mamluks in the Siege of Acre. When Pope Nicholas IV learned of this, he wrote to Arghun, again asking him to be baptized and to fight against the Mamluks.[102] But Arghun had died on March 10, 1291, and Pope Nicholas IV died as well in March 1292, putting an end to their efforts towards combined action.[103]

Ghazan (1295–1304)

See also: Mongol invasions of Syria and Mongol raids into PalestineMain article: GhazanAfter Arghun's death, he was followed in rapid succession by two brief and fairly ineffective leaders, one of whom only held power for a few months. Stability was restored when Arghun's son Ghazan took power in 1295, though to secure cooperation from other influential Mongols, he made a public conversion to Islam when he took the throne, marking a major turning point in the state religion of the Ilkhanate. Despite being an official Muslim though, Ghazan remained tolerant of multiple religions, and worked to maintain good relations with his Christian vassal states such as Cilician Armenia and Georgia.[104]

In 1299, he made the first of what were to be three attempts to invade Syria.[105] As he launched his new invasion, he also sent letters to the Franks of Cyprus (the King of Cyprus, and the heads of the military orders), inviting them to come join him in his attack on the Mamluks in Syria.[106][107]

The Mongols successfully took the city of Aleppo, and were there joined by their vassal King Hethum II, whose forces participated in the rest of the offensive. The Mongols soundly defeated the Mamluks in the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar, on December 23 or 24, 1299.[108] This success in Syria led to wild rumors in Europe that the Mongols had successfully re-captured the Holy Land, and had even conquered the Mamluks in Egypt and were on a mission to conquer Tunisia in northern Africa. But in reality, Jerusalem had been neither taken nor even besieged.[109] All that had been managed were some Mongol raids into Palestine in early 1300. The raids went as far as Gaza, passing through several towns, probably including Jerusalem. But when the Egyptians again advanced from Cairo in May, the Mongols retreated without resistance.[110]

In July 1300, the Crusaders launched naval operations to press the advantage.[111] A fleet of sixteen galleys with some smaller vessels was equipped in Cyprus, commanded by King Henry of Cyprus and Jerusalem, accompanied by his brother Amalric, Lord of Tyre, the heads of the military orders, and Ghazan's ambassador "Chial" (Isol the Pisan).[110][111][112] The ships left Famagusta on July 20, 1300, to raid the coasts of Egypt and Syria: Rosette, Alexandria, Acre, Tortosa, and Maraclea, before returning to Cyprus.[110][112]

Ruad expedition

Main article: Fall of RuadAfter the naval raids, the Cypriots attempted a major operation to re-take the former Templar stronghold of Tortosa.[6][107][113][114]

The Cypriots prepared the largest force they could muster at the time, approximately 600 men: 300 under Amalric of Lusigan, son of Hugh III of Cyprus, and similar contingents from the Templars and Hospitallers.[113] In November 1300 they attempted to occupy Tortosa on the mainland, but were unable to gain control of the city. The Mongols were delayed, and the Cypriots moved offshore to the nearby island of Ruad to establish a base.[113]

The Mongols continued to be delayed, and the bulk of the Crusader forces returned to Cyprus, leaving only a garrison on Ruad.[6][114] In February 1301, Ghazan's Mongols finally made a new advance into Syria. The force was commanded by the Mongol general Kutlushka, who was joined by Armenian troops, and Guy of Ibelin and John, lord of Giblet. But despite a force of 60,000, Kutluskha could do little else than engage in some raids around Syria, and then retreated.[6]

Plans for combined operations between the Europeans and the Mongols were again made for the following winter offensives, in 1301 and 1302. But in mid-1301 the island of Ruad was attacked by the Egyptian Mamluks. After a lengthy siege, the island surrendered in 1302 or 1303.[113][114] The Mamluks slaughtered many of the inhabitants, and captured the surviving Templars to send them to prison in Cairo.[113]

In late 1301, Ghazan sent letters to the Pope asking him to send troops, priests, and peasants, to make the Holy Land a Frank state again.[115]

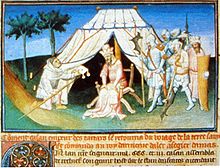

In an image from Marco Polo's 15th century Livre des Merveilles, Ghazan orders the King of Armenia Hethum II to accompany Kutlushka on the 1303 attack on Damascus.[116]

In 1303, Ghazan sent another letter to Edward I, via Buscarello de Ghizolfi, who had also been an ambassador for Arghun. The letter reiterated their ancestor Hulagu's promise that the Ilkhans would give Jerusalem to the Franks in exchange for help against the Mamluks. That year, the Mongols again attempted to invade Syria, appearing in great strength (about 80,000) together with the Armenians. But they were again defeated at Homs on March 30, 1303, and at the decisive Battle of Shaqhab, south of Damascus, on April 21, 1303.[48] It is considered to be the last major Mongol invasion of Syria.[117]

Ghazan died on May 10, 1304, and Frankish dreams of a rapid reconquest of the Holy Land were destroyed.[118]

Oljeitu (1304–1316)

Oljeitu, also named Mohammad Khodabandeh, was great-grandson of Ilkhanate founder Hulagu, and brother and successor of Ghazan. In his youth he at first converted to Buddhism, and then later to Sunni Islam with his brother Ghazan, and changed his first name to the Islamic Muhammad.[119]

In April 1305, Oljeitu sent letters to Philip IV of France, Pope Clement V, and Edward I of England. As had his predecessors, Oljeitu offered a military collaboration between the Mongols and the Christian nations of Europe, against the Mamluks.[48]

European nations prepared a crusade, but were delayed. In the meantime Oljeitu launched a last campaign against the Mamluks (1312–13), in which he was unsuccessful. A final settlement with the Mamluks would only be found when Oljeitu's son Abu Sa'id signed the Treaty of Aleppo in 1322.[48]

Last contacts

In the 14th century, diplomatic contact continued between the Europeans and the Mongols, until the Ilkhanate dissolved in the 1330s, and the ravages of the Black Death in Europe caused contact with the East to be severed.[120]

A few marital alliances between the Mongols and Christian rulers continued between the Christians and the Mongols of the Golden Horde, as when the Byzantine emperor Andronicus II gave daughters in marriage to the Golden Horde ruler Toqto'a, as well as his successor Uzbek (1312–1341).[121]

After Abu Sa'id, relations between Christian princes and the Mongols became very sparse. Abu Sa'id died in 1335 with neither heir nor successor, and the Mongol state lost its status after his death, becoming a plethora of little kingdoms run by Mongols, Turks, and Persians.[12]

In 1336, an embassy to the French Pope Benedict XII in Avignon was sent by Toghun Temür, the last Yuan emperor in Dadu. The embassy was led by two Genoese travelers in the service of the Mongol emperor, who carried letters representing that the Mongols had been eight years (since Archbishop John of Monte Corvino's death) without a spiritual guide, and earnestly desired one.[122] Pope Benedict appointed four ecclesiastics as his legates to the khan's court. In 1338, a total of 50 ecclesiastics were sent by the Pope to Peking, among them John of Marignolli, who returned to Avignon in 1353 with a letter from the Yuan emperor to Pope Innocent VI. But soon, the native Chinese rose up and drove out the Mongols from China, launching the Ming Dynasty in 1368. By 1369, all foreign influences, from Mongols to Christians, Manichaeans, and Buddhists, were expelled by the Ming Dynasty.[123]

In the early 15th century, Timur (Tamerlane), resumed Timurid relations with Europe, attempting to form an alliance against the Egyptian Mamluks and the Ottoman Empire, and engaged in communications with Charles VI of France and Henry III of Castile, but died in 1405.[12][124][125][126][127]

Dispute about the existence of the Franco-Mongol alliance

There is dispute among historians as to the existence, extent, or even wisdom of an alliance.[8] The mainstream view describes the contacts as a series of attempts, missed opportunities, and failed negotiations, though a few historians have argued there was an actual alliance.[2][128][129][130] Even among the latter though, there is dispute as to the details: the French historian Jean Richard argues that an alliance began around 1263,[131] while another French historian, Alain Demurger, says that an alliance was not sealed until 1300.[132] Other historians lament that the lack of alliance was a "lost opportunity".[133] According to the 20th century historian Runciman, "Had the Mongol alliance been achieved and honestly implemented by the West, the existence of Outremer would almost certainly have been prolonged. The Mameluks would have been crippled if not destroyed; and the Ilkhanate of Persia would have survived as a power friendly to the Christians and the West".[134] However, these historians were also writing from the benefit of hindsight.[135][136]

Most other historians, however, stress that there were only attempts towards such an alliance, which ultimately ended in failure.[2][103][129] Joshua Prawer said simply, "The attempts of the crusaders to create an alliance with the Mongols failed."[137] Steven Runciman lamented that "chances of a Mongol alliance with the Christians faded out."[138] David Nicolle said that the Mongols were "potential allies",[139] but that overall the major players were the Mamluks and the Mongols, and that the Christians were just "pawns in a greater game."[140] Reuven Amitai stated that the closest thing to actual Mongol-Frankish military coordination was when Prince Edward of England attempted to coordinate activities with Abaga in 1271. Amitai also mentioned the other attempts towards cooperation, but said, "In none of these episodes, however, can we speak of Mongols and troops from the Frankish West being on the Syrian mainland at the same time."[83] Christopher Atwood, in the 2004 Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire summed up the relations between Western Europe and the Mongols: "Despite numerous envoys and the obvious logic of an alliance against mutual enemies, the papacy and the Crusaders never achieved the often-proposed alliance against Islam."[2]

Reasons for failure

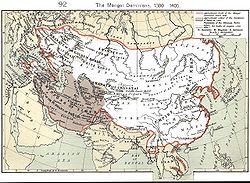

The Mongol Empire, ca. 1300. The gray area is the later Timurid empire. The geographic distance between the Ilkhanid Mongols, along with their Great Khan in Khanbalic, and the Europeans was large.

The Mongol Empire, ca. 1300. The gray area is the later Timurid empire. The geographic distance between the Ilkhanid Mongols, along with their Great Khan in Khanbalic, and the Europeans was large.

There has been much discussion among historians as to why the Franco-Mongol alliance never came together, and why despite all the diplomatic contacts, that it stayed a chimera, a fantasy.[3][8] Peter Jackson, in his 2005 book The Mongols and the West, 1221-1410, discussed multiple reasons for the failure of an alliance.[141]

The Mongols at that stage in their empire, were not entirely focused on expanding to the West. By the late 13th century, the Mongol leaders were several generations removed from the great Genghis Khan, and internal disruption was brewing. The original nomadic Mongols from the day of Genghis had become more settled, and had turned into administrators instead of conquerors. Battles were springing up that were Mongol against Mongol, which took troops away from the front in Syria.[141]

There was confusion within Europe, as to the differences between the Mongols of the Ilkhanate in the Holy Land, and the Mongols of the Golden Horde, who were making attacks on Eastern Europe, in Hungary and Poland. Within the Mongol Empire, the Ilkhanids and the Golden Horde considered each other enemies, but it took time for Western observers to be able to distinguish between the different parts of the Mongol Empire.[141]

There was decreased interest in Europe in pursuing the Crusades. After the loss of Jerusalem to Saladin in 1187, and an increasingly bleak situation for the Crusaders in Egypt, enthusiasm for the Crusades waned. Monarchs often gave lip service to the idea of going on Crusade, as a way of making an emotional appeal to their subjects, but in reality they would take years to prepare, and sometimes never actually left to go do battle. Internal wars in Europe, such as the War of the Vespers, were also distracting attention, and making it less likely for European nobles to want to commit their military to the Crusades, when they needed them more at home.[141]

Economics played a factor, as the cost of Crusading had been steadily increasing. Some monarchs responded positively to Mongol inquiries, but became vague and evasive when asked to actually commit troops and resources. Logistics also became more difficult – the Egyptian Mamluks were genuinely concerned about the threat of another wave of Crusader forces, so each time the Mamluks captured another castle or port, instead of occupying it, they systematically destroyed it so that it could never be used again. This both made it more difficult for the Crusaders to plan military operations, and increased the expense of those operations.[141]

There were concerns among the Europeans about the longterm goals of the Mongols. The early Mongol diplomacy had been not a simple offer of cooperation, but a clear demand for submission. There was awareness that the Mongols would not have been content to stop at the Holy Land, but were on a clear quest for world domination. It was only in their later communications with Europe that the Mongol diplomats started to adopt a more conciliatory tone; but they still used language that more implied command than entreaty. If the Mongols had achieved a successful alliance with the West, and destroyed the Mamluk Sultanate, there is little doubt that the Mongols would have then proceeded to conquer Africa. There, no strong state could have stood in their way until Morocco. The Mongols would have turned upon the Franks of Cyprus and the Byzantines. Even the Armenian King, the most enthusiastic advocate of Western-Mongol collaboration, freely admitted that the Mongol leader was not inclined to listen to European advice. His advice was that even if working together, that European armies and Mongol armies should avoid contact because of the Mongol arrogance.[141]

Jackson further points out that the court historians of Mongol Iran made no mention whatsoever of the communications between the Ilkhans and the Christian West, and barely mentioned the Franks at all. The communications were evidently not seen as important by the Mongols, and Jackson argues that the communications may have even been seen as embarrassing. The Mongol leader Ghazan, a converted Muslim since 1295, might not have wanted to be seen as trying to gain the assistance of infidels, against his fellow Muslims in Egypt. When Mongol historians did make notes of foreign territories, the areas were usually categorized as either "enemies", "conquered", or "in rebellion." The Franks, in that context, were listed in the same category as the Egyptians, in that they were enemies to be conquered. The idea of "ally" was foreign to the Mongols.[141]

There was not much support among the populace in Europe for a Mongol alliance. Writers in Europe were creating "recovery" literature with their ideas about how best to recover the Holy Land, but few mentioned the Mongols as a genuine possibility. In 1306, when Pope Clement V asked the leaders of the military orders, Jacques de Molay and Fulk de Villaret, to present their proposals for how the crusades should proceed, neither of them factored in any kind of a Mongol alliance. A few later proposals talked briefly about the Mongols as being a force that could invade Syria and keep the Mamluks distracted, but not as a force that could be counted on for cooperation.[141]

Notes

- ^ Many people in the East used the word "Frank" to denote a European of any variety.

- ^ a b c d e f Atwood,"Western Europe and the Mongol Empire" Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p. 583. "Despite numerous envoys and the obvious logic of an alliance against mutual enemies, the papacy and the Crusaders never achieved the often-proposed alliance against Islam".

- ^ a b Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 4. "The failure of Ilkhanid-Western negotiations, and the reasons for it, are of particular importance in view of the widespread belief in the past that they might well have succeeded."

- ^ a b c Ryan, "Christian wives of Mongol khans"

- ^ a b c Morgan, "The Mongols and the Eastern Mediterranean" p. 204. "The authorities of the crusader states, with the exception of Antioch, opted for a neutrality favourable to the Mamluks."

- ^ a b c d Edbury. Kingdom of Cyprus. p. 105. http://books.google.com/books?id=DmYeAuWUPK8C&pg=PA105.

- ^ Demurger, "The Isle of Ruad", The Last Templar

- ^ a b c See Abate History in Dispute: The Crusades, 1095-1291, pp. 182–186, where the question that is debated is, "Would a Latin-Ilkhan Mongol alliance have strengthened and preserved the Crusader States?'"

- ^ a b Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 46. See also pp. 181–182. "For the Mongols the mandate came to be valid for the whole world and not just for the nomadic tribes of the steppe. All nations were de jure subject to them, and anyone who opposed them was thereby a rebel (bulgha). In fact, the Turkish word employed for 'peace' was that used also to express subjection... There could be no peace with the Mongols in the absence of submission."

- ^ a b Foltz, Religions of the Silk Road, p. 111-112

- ^ Amitai, "Mongol raids into Palestine (AD 1260 and 1300)", p. 236

- ^ a b c d Knobler, "Pseudo-Conversions" pp. 181-197

- ^ Quoted in Runciman, History of the Crusades 3, p. 246

- ^ a b c d Morgan, The Mongols, p. 133–138

- ^ Richard, The Crusades p. 422 "In all the conversations between the popes and the il-khans, this difference of approach remained: the il-khans spoke of military cooperation, the popes of adhering to the Christian faith."

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 72

- ^ Tyerman, pp. 770–771

- ^ Riley-Smith, pp. 289–290

- ^ Tyerman, p. 772

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 90

- ^ Morgan, The Mongols (2nd ed.) p. 102

- ^ Dawson (ed.), The Mongol Mission, p. 86

- ^ Sinor, in Setton, History of the Crusades, p.522 "The Pope's reply to Baidju's letter, Viam agnoscere veritatis, dated November 22, 1248, and probably carried back by Aibeg and Sargis." Note that Setton refers to the letter as "Viam agnoscere" though the actual letter uses the text "Viam cognoscere"

- ^ Hindley, p. 193

- ^ Bournotian, A Concise History p. 109. "It was at this juncture that the main Mongol armies appeared [in Armenia] in 1236. The Mongols swiftly conquered the cities. Those who resisted were cruelly punished, while submitting were rewarded. News of this spread quickly and resulted in the submission of all of historic Armenia and parts of Georgia by 1245.... Armenian and Georgian military leaders had to serve in the Mongol army, where many of them perished in battle. In 1258 the Ilkhanid Mongols, under the leadership of Hulagu, sacked Baghdad, ended the Abbasis Caliphate and killed many Muslims."

- ^ Stewart, "The Logic of Conquest" p.8

- ^ Stewart, "Logic of Conquest", p. 8. "The Armenian king saw alliance with the Mongols -- or, more accurately, swift and peaceful subjection to them -- as the best course of action."

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 74. "King Het'um of Lesser Armenia, who had reflected profoundly upon the deliverance afforded by the Mongols from his neighbbours and enemies in Rum, sent his brother, the Constable Smbat (Sempad) to Guyug's court to offer his submission."

- ^ Bournotian, A Concise History p. 100. "Smbat met Kubali's brother, Mongke Khan and in 1247, made an alliance against the Muslims"

- ^ Nersessian, "The Kingdom of Cilician Armenia" in Setton's Crusades, p. 653. "Hetoum tried to win the Latin princes over to the idea of a Christian-Mongol alliance, but could convince only Bohemond VI of Antioch."

- ^ Lebedel Les Croisades, Origines et consequences, p. 75. "The Barons of the Holy Land refused an alliance with the Mongols, except for the king of Armenia and Bohemond VI, prince of Antioch and Count of Tripoli"

- ^ a b c d e Jackson. Mongols and the West. p. 167–168. http://books.google.com/books?id=7FLUMVIqIvwC&pg=PA167.

- ^ a b c Tyerman, God's War, p. 806

- ^ Richard, The Crusades p. 410. "Under the influence of his father-in-law, the king of Armenia, the prince of Antioch had opted for submission to Hulegu"

- ^ Saunders, History of the Mongol Conquests p. 115

- ^ Richard, The Crusades p. 416. "In the meantime, [Baibars] conducted his troops to Antioch, and started to besiege the city, which was saved by a Mongol intervention"

- ^ a b c Richard, The Crusades, pp. 414-420

- ^ Hindley, p. 206

- ^ Quoted in Grousset, Histoire des Croisades III p.650

- ^ a b c d Tyerman, God's War, pp. 815-818

- ^ Jackson "Crisis in the Holy Land"

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 181

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 99

- ^ Tyerman, God's War, p. 798. "Louis's embassy under Andrew of Longjumeau had returned in 1251 carrying a demand from the Mongol regent, Oghul Qaimush, for annual tribute, not at all what the king had anticipated."

- ^ Sinor, p. 524

- ^ Tyerman, God's War, pp. 789-798

- ^ Daftary, p. 60

- ^ a b c d e Calmard "France" article in Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ Sinor, p. 531

- ^ Demurger, "Croisades et Croises", p.285. "It really seems that Saint Louis's initial project in his second Crusade was an operation coordinated with the offensive of the Mongols."

- ^ a b Richard, The Crusades, pp. 428-434

- ^ Grousset, Histoire des Crusades III, p.647

- ^ Runciman, History of the Crusades 3, p. 303

- ^ Lane, p. 243

- ^ a b Angold. Cambridge History of Christianity. p. 387. "In May 1260, a Syrian painter gave a new twist to the iconography of the Exaltation of the Cross by showing Constantine and Helena with the features of Hulegu and his Christian wife Doquz Khatun"

- ^ Le Monde de la Bible N.184 July–August 2008, p.43

- ^ a b c Joseph. Muslim-Christian Relations. p. 16. http://books.google.com/books?id=lKaL3_dfFJAC&pg=PA16.

- ^ a b Folda, Jaroslav. Crusader art in the Holy Land: from the Third Crusade to the fall of Acre. pp. 349–350. http://books.google.com/books?id=Xifq5OE7174C&pg=PA349.

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 120

- ^ Takahashi. Barhebraeus: a bio-bibliography. p. 102. http://books.google.com/books?id=4ovTbDkRDOIC&pg=PA102.

- ^ Runciman, History of the Crusades 3 p. 304

- ^ Irwin, "Rise of the Mamluks", p. 616

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, pp. 414–415. "He [Qutuz] reinstated the emirs expelled by his predecessor, then assembled a large army, swollen by those who had fled from Syria during Hulegu's offensive, and set about recovering territory lost by the Muslims. Scattering in passage the thousand men left at Gaza by the Mongols, and having negotiated a passage along the coast with the Franks (who had received his emirs in Acre), he met and routed Kitbuqa's troops at Ayn Jalut."

- ^ Jackson, p. 116

- ^ Richard, p. 411

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 105

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 115

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, p. 425. "They allowed the Mamluks to cross their territory, in exchange for a promise to be able to purchase at a low price the horses captured from the Mongols."

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 165

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, pp. 409-414

- ^ Tyerman, p. 807

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, pp. 421-422 "What Hulegu was offering was an alliance. And, contrary to what has long been written by the best authorities, this offer was not in response to appeals from the Franks."

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 166

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, p. 436. "In 1264, to the coalition between the Franks, Mongols and Byzantines, responded the coalition between the Golden Horde and the Mamluks."

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, p. 414. "In Frankish Syria, meanwhile, events had taken another direction. There was no longer any thought of conducting a crusade against the Mongols; the talk was now of a crusade in collaboration with them."

- ^ Oxford history of Byzantium, p. 258

- ^ Bisson, p. 70

- ^ a b Hindley, The Crusades pp. 205-207

- ^ Nicolle, The Crusades, p. 47

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, p. 433. "On landing at Acre, Edward at once sent his messengers to Abaga. He received a reply only in 1282, when he had left the Holy Land. The il-khan apologized for not having kept the agreed rendezvous, which seems to confirm that the crusaders of 1270 had devised their plan of campaign in the light of Mongol promises, and that these envisaged joint operation in 1271. In default of his own arrival and that of his army, Abaga ordered the commander of this forces stationed in Turkey, the 'noyan of the noyans', Samaghar, to descend into Syria to assist the crusaders."

- ^ Sicker. Islamic World in Ascendancy. p. 123. http://books.google.com/books?id=v3AdA-Ogl34C&pg=PA123. "Abaqa now decided to send some 10,000 Mongol troops to join Edward's Crusader army"

- ^ Hindley, p. 207

- ^ a b Amitai, p. 161, "Edward of England and Abagha Ilkhan: A reexamination of a failed attempt at Mongol-Frankish cooperation"

- ^ a b Richard, The Crusades, p. 487. "1274: Promulgation of a Crusade, in liaison with the Mongols".

- ^ Setton, Papacy and the Levant, p. 116

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, p. 422

- ^ Balard, Les Latins en Orient (XIe-XVe siècle), p. 210. "Le Pape Grégoire X s’efforce alors de mettre sur pied un vaste programme d’aide à la Terre Sainte, les "Constitutions pour le zèle de la foi", qui sont acceptées au Concile de Lyon de 1274. Ce texte prévoit la levée d’une dime pendant trois ans pour la croisade, l’interdiction de tout commerce avec les Sarasins, la fourniture de bateaux par les républiques maritimes italiennes, et une alliance de l’Occident avec Byzance et l’Il-Khan Abagha".

- ^ a b c d e f g Richard, The Crusades, p. 452-456

- ^ a b c Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 168

- ^ a b c Amitai. Mongols and Mamluks. pp. 185–186. http://books.google.com/books?id=dIaFbxD64nUC&pg=PA185.

- ^ a b c Harpur. The Crusades: The Two Hundred Years War. p. 116. http://books.google.com/books?id=OCGuWrNyjiEC&pg=PA116.

- ^ Jackson, "Mongols and Europe" p. 715

- ^ Grands Documents de l'Histoire de France, Archives Nationales de France, p.38, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Jackson, The Mongols and the West p. 169]

- ^ Fisher, William Bayne; Boyle, John Andrew. The Cambridge history of Iran. p. 370. http://books.google.com/books?id=BxRwJUrnr20C&pg=PA370.

- ^ Rossabi, p. 99

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 170. "Arghun had persisted in the quest for a Western alliance right down to his death without ever taking the field against the mutual enemy."

- ^ Mantran, "A Turkish or Mongolian Islam" in The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 1250-1520, p. 298

- ^ Phillips, Medieval Expansion of Europe, p. 126

- ^ a b c Richard. Crusades, c.1071–c.1291. p. 455. http://books.google.com/books?id=KszvJSv7t30C&pg=PA455.

- ^ a b c Jackson, "The Mongols and Europe", p. 715

- ^ a b c Jackson. Mongols and the West, 1221–1410. p. 169. http://books.google.com/books?id=7FLUMVIqIvwC&pg=PA169.

- ^ a b Tyerman, God's War, p. 816. "The Mongol alliance, despite six further embassies to the west between 1276 and 1291, led nowhere. The prospect of an anti-Mamluk coalition faded as the westerners' inaction rendered them useless as allies for the Mongols, who, in turn, would only seriously be considered by western rulers as potential partners in the event of a new crusade which never happened."

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, pp. 455–456. "When Ghazan got rid of him [Nawruz] (March 1297), he revived his projects against Egypt, and the rebellion of the Mamluk governor of Damascus, Saif al-Din Qipchaq, provided him with the opportunity for a new Syrian campaign; Franco-Mongol cooperation thus survived both the loss of Acre by the Franks and the conversion of the Mongols of Persia to Islam. It was to remain one of the givens of crusading politics until the peace treaty with the Mamluks, which was concluded only in 1322 by the khan Abu Said."

- ^ Amitai, "Ghazan's first campaign into Syria (1299–1300)", p. 222

- ^ Barber The Trial of the Templars 2nd ed., p. 22: "The aim was to link up with Ghazan, the Mongol Il-Khan of Persia, who had invited the Cypriots to participate in joint operations against the Mamluks".

- ^ a b Nicholson. The Knights Hospitaller. p. 45. http://books.google.com/books?id=oGppfVJMKjsC&pg=PA45.

- ^ Demurger, The Last Templar, p. 99

- ^ Phillips, p. 128

- ^ a b c Schein "Gesta Dei per Mongolos" 1979, p. 811

- ^ a b Jotischky. Crusading and the Crusader states. p. 249. http://books.google.com/books?id=yG9OqY08E98C&pg=249.

- ^ a b Demurger, The Last Templar, p. 100

- ^ a b c d e Malcolm Barber. The Trial of the Templars. p. 22. http://books.google.com/books?id=rqfE2l0cowgC&pg=RA1-PA22.

- ^ a b c Jackson. The Mongols and the West. p. 171. http://books.google.com/books?id=7FLUMVIqIvwC&pg=PA171.

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, p. 469

- ^ Mutafian, "Le Royaume Armenien de Cilicie", p.74-75

- ^ Nicolle, The Crusades, p. 80

- ^ Demurger, p. 109

- ^ Stewart, Armenian Kingdom, p. 181

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 216

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 203

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 314

- ^ Phillips, p. 112

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 360

- ^ Sinor. Inner Asia. p. 190. http://books.google.com/books?id=foS-y-ShWJ0C&pg=PA190.

- ^ Daniel. Culture and customs of Iran. p. 25. http://books.google.com/books?id=8ZIjyEi1pd8C&pg=PA25.

- ^ Wood, Frances. The Silk Road: Two Thousand Years in the Heart of Asia. p. 136. http://books.google.com/books?id=zvoCv3h2QCsC&pg=PA136.

- ^ Jackson. The Mongols and the West. p. 4. http://books.google.com/books?id=7FLUMVIqIvwC&pg=PA4.

- ^ a b Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 173. "In their successive attempts to secure assistance from the Latin world, the Ilkhans took care to select personnel who would elicit the confidence of Western rulers and to impart a Christian complexion to their overtures."

- ^ Morgan, The Mongols, 2nd ed., p. 136. "This has long been seen as a 'missed opportunity' for the Crusaders. According to that opinion, most eloquently expressed by Grousset and frequently repeated by other scholars, the Crusaders ought to have allied themselves with the pro-Christian, anti-Muslim Mongols against the Mamluks. They might thus have prevented their own destruction by the Mamluks in the succeeding decades, and possibly even have secured the return of Jerusalem by favour of the Mongols."

- ^ Richard, The Crusades, pp. 424-469

- ^ Demurger, The Last Templar, p. 100. "Above all, the expedition made manifest the unity of the Cypriot Franks and, through a material act, put the seal on the Mongol alliance."

- ^ Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 119

- ^ Runciman, History of the Crusades 3, p. 402

- ^ Burger, A Lytell Cronycle, pp. xiii-xiv. "The refusal of the Latin Christian states in the area to follow Hethum's example and adapt to changing conditions by allying themselves with the new Mongol empire must stand as one of the saddest of the many failures of Outremer."

- ^ Nicolle, The Mongol Warlords, p. 114. "In later years Christian chroniclers would bemoan a lost opportunity in which Crusaders and Mongols might have joined forces to defeat the Muslims. But they were writing from the benefit of hindsight, after the Crusader States had been destroyed by the Muslim Mamluks."

- ^ Prawer, The Crusaders' Kingdom p. 32. "The attempts of the crusaders to create an alliance with the Mongols failed."

- ^ Runciman, pp. 439-440

- ^ Nicolle, The Crusades, p. 42. "The Mongol Hordes under Genghis Khan and his descendants had already invaded the eastern Islamic world, raising visions in Europe of a potent new ally, which would join Christians in destroying Islam. Even after the Mongol invasion of Orthodox Christian Russia, followed by their terrifying rampage across Catholic Hungary and parts of Poland, many in the West still regarded the Mongols as potential allies."

- ^ Nicolle, The Crusades, p. 44. "Eventually the conversion of the Il-Khans (as the Mongol occupiers of Iran and Iraq were known) to Islam at the end of the 13th century meant that the struggle became one between rival Muslim dynasties rather than between Muslims and alien outsiders. Though the feeble Crusader States and occasional Crusading expeditions from the West were drawn in, the Crusaders were now little more than pawns in a greater game."

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jackson, Mongols and the West, pp. 165-185

References

- Abate, Mark T., Marx, Todd (2002). History in Dispute: The Crusades, 1095-1291. 10. Detroit, Michigan, USA: St. James Press. ISBN 1558624546.

- Amitai-Preiss, Reuven (1995). Mongols and Mamluks: The Mamluk-Ilkhanid War, 1260–1281. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521462266.

- Amitai, Reuven (1987). "Mongol Raids into Palestine (AD 1260 and 1300)". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (Cambridge, WK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press) (2): 236–255. JSTOR 25212151.

- Amitai, Reuven (2001). "Edward of England and Abagha Ilkhan: A reexamination of a failed attempt at Mongol-Frankish cooperation". In Gervers, Michael; Powell, James M. (editors). Tolerance and Intolerance: Social Conflict in the Age of the Crusades. Syracuse, New York, USA: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815628699. http://books.google.com/books?id=n9dEpOsfVdIC&lpg=PP1&pg=PA75#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Angold, Michael, ed (2006). Cambridge History of Christianity: Eastern Christianity. 5. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CHOL9780521811132. ISBN 0521811139.

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York, New York, USA: Facts on File, Inc.. ISBN 0-8160-4671-9.

- Balard, Michel (2006). Les Latins en Orient (XIe-XVe siècle). Paris, FR: Presses Universitaires de France. ISBN 2130518117.

- Barber, Malcolm (2001). The Trial of the Templars (2nd ed.). Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-67236-8.

- Bisson, Thomas N. (1986). The Medieval Crown of Aragon: A Short History. New York, New York, USA: Clarendon Press [Oxford University Press]. ISBN 9780198219873.

- Bournoutian, George A. (2002). A Concise History of the Armenian People: From Ancient Times to the Present. Costa Mesa, California, USA: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 1568591411.

- Burger, Glenn (1988). A Lytell Cronycle: Richard Pynson's Translation (c. 1520) of La Fleur des histoires de la terre d’Orient (Hetoum c. 1307). Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0802026265.

- Calmard, Jean. "Encyclopædia Iranica". In Yarshater, Ehsan. Costa Mesa, California, USA: Mazda Publishers. http://www.iranica.com/articles/france-index. Retrieved March 27, 2010.

- Daftary, Farhad (1994). The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Isma'ilis. London; New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 9781850437055.

- Daniel, Elton L.; Ali Akbar Mahdi (2006). Culture and Customs of Iran. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313320538. http://books.google.com/books?id=8ZIjyEi1pd8C&pg=PA25.

- Dawson, Christopher (1955). The Mongol Mission: Narratives and Letters of the Franciscan Missionaries in Mongolia and China in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Translated by a nun of Stanbrook Abbey. New York, New York, USA: Sheed and Ward. ISBN 1405135395.

- Demurger, Alain (2006) (in French). Croisades et Croisés au Moyen Age. Paris, FR: Flammarion. ISBN 9782080801371.

- Demurger, Alain (2005) [First published in French in 2002, translated to English in 2004 by Antonia Nevill]. The Last Templar. London, UK: Profile Books. ISBN 2228902357.

- Edbury, Peter W. (1991). Kingdom of Cyprus and the Crusades, 1191-1374. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521268761. http://books.google.com/books?id=DmYeAuWUPK8C&pg=PA105.

- Grousset, René (1936) (in French). Histoire des Croisades III, 1188-1291 L'anarchie franque. Paris, FR: Perrin. ISBN 2-262-02569-X.

- Foltz, Richard C. (1999). Religions of the Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Exchange from Antiquity to the Fifteenth Century. New York, New York, USA: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-23338-8.

- Harpur, James (2008). The Crusades The Two Hundred Years War: The Clash Between the Cross and the Crescent in the Middle East. New York, New York, USA: Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 9781404213678. http://books.google.com/books?id=OCGuWrNyjiEC&pg=PA116.

- Hindley, Geoffrey (2004). The Crusades: Islam and Christianity in the Struggle for World Supremacy. New York, New York, USA: Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0786713445.

- Irwin, Robert. "The Rise of the Mamluks". In Abulafia, David; McKitterick, Rosamond (editors). The New Cambridge Medieval History V: c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 616. ISBN 052136289X.

- Jackson, Peter (July 1980). "The Crisis in the Holy Land in 1260". The English Historical Review (London, UK; New York, New York, USA: Oxford University Press) 95 (376): 481–513. doi:10.1093/ehr/XCV.CCCLXXVI.481. ISSN 0013-8266. JSTOR 568054.

- Jackson, Peter (2000). "The Mongols and Europe". In Abulafia, David; McKitterick, Rosamond (editors). The New Cambridge Medieval History V: c. 1198–c. 1300. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA. p. 703. http://books.google.com/books?id=bclfdU_2lesC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_v2_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- Jackson, Peter (2005). The Mongols and the West: 1221-1410. Harlow, UK; New York, New York, USA: Longman. ISBN 978-0582368965.

- Joseph, John (1983). Muslim-Christian Relations and Inter-Christian Rivalries in the Middle East: The Case of the Jacoites in an Age of Transition. Albany, New York, USA: SUNY Press. ISBN 9780873956000. http://books.google.com/books?id=lKaL3_dfFJAC&pg=PA16.

- Jotischky, Andrew (2004). Crusading and the Crusader States. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education. ISBN 0582418518. http://books.google.com/books?id=yG9OqY08E98C&pg=249.

- Knobler, Adam (Fall 1996). "Pseudo-Conversions and Patchwork Pedigrees: The Christianization of Muslim Princes and the Diplomacy of Holy War". Journal of World History (Honolulu, HI, USA: University of Hawai'i Press) 7 (2): 181–197. doi:10.1353/jwh.2005.0040. ISSN 1045-6007. http://muse.jhu.edu/login?uri=/journals/journal_of_world_history/v007/7.2knobler.html.

- Lane, George (2006). Daily Life in the Mongol Empire. Westport, Connecticut, USA: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313332265.

- Lebédel, Claude (2006) (in French). Les Croisades, Origines et Conséquences. Rennes, FR: Editions Ouest-France. ISBN 2737341361.

- Mantran, Robert (1986). "A Turkish or Mongolian Islam". In Fossier, Robert. The Cambridge Illustrated History of the Middle Ages: 1250-1520. 3. trans. Hanbury-Tenison, Sarah. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. p. 298. ISBN 9780521266468.

- Marshall, Christopher (1994). Warfare in the Latin East, 1192–1291. Cambridge, UK; New York, New York, USA: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521477420.

- Michaud, Yahia (Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies) (2002) (in French). Ibn Taymiyya, Textes Spirituels I-XVI. Le Musulman, Oxford-Le Chebec. http://www.muslimphilosophy.com/it/works/ITA%20Texspi.pdf.

- Morgan, David (June 1989). Arbel, B.; et al.. ed. "The Mongols and the Eastern Mediterranean: Latins and Greeks in the Eastern Mediterranean after 1204". Mediterranean Historical Review (Tel Aviv, Illinois: Routledge) 4 (1): 204. doi:10.1080/09518968908569567. ISSN 0951-8967.

- Morgan, David (2007). The Mongols (2nd ed.). Malden, Massachusetts, USA; Oxford, UK; Carlton, Victoria, AU: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405135399.

- Mutafian, Claude (2002) (in French). Le Royaume Arménien de Cilicie, XIIe-XIVe siècle. Paris, FR: CNRS Editions. ISBN 2271051053.

- Nersessian, Sirarpie Der (1969). "The Kingdom of Cilician Armenia". In Hazard, Harry W. and Wolff, Robert Lee. (Kenneth M. Setton, general editor). A History of the Crusades: The Later Crusades, 1189-1311. 2. Madison, Wisconsin, USA: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 630–660. ISBN 0299048446. http://books.google.com/books?id=v1Kx3QGYsdcC&printsec=frontcover#PPA630,M1.

- Nicholson, Helen (2001). The Knights Hospitaller. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK; Rochester, New York, USA: The Boydell Press. ISBN 0851158455. http://books.google.com/books?id=oGppfVJMKjsC&pg=PA45.

- Nicolle, David (2001). The Crusades. Essential Histories. Oxford, UK: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84176-179-4.

- Nicolle, David; Hook, Richard (2004). The Mongol Warlords: Genghis Khan, Kublai Khan, Hulegu, Tamerlane. London, UK: Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1860194079.

- Phillips, John Roland Seymour (1998). The Medieval Expansion of Europe (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198207409.