- Mongol invasions of Vietnam

-

Mongol-Vietnamese Wars

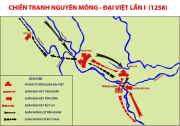

Map of the first Mongolian invasion of VietnamDate 1257-58, 1284-85 and 1287-88 Location Đại Việt and Champa Result Decisive Mongol military defeats[1]. To avoid further conflict, Đại Việt and Champa agreed to a titular tributary relationship with the Mongol Empire Belligerents Yuan Dynasty of the Mongol Empire Vietnamese states: - Đại Việt under the Trần Dynasty

- Champa Dynasty

Commanders and leaders Mongke Khan

Kublai Khan

Uriyankhadai

Aju

Sodu

Toghan

Umar

Abachi

Fanji

Aqatai

ArikhgiyaTran Thai Tong

Tran Thanh Tong

Trần Nhân Tông

Tran Hung Dao

Tran Quang Khai

Jaya Indravarman VIStrength about 25.000-55.000 in 1257, More than 100,000 soldiers and 400.000 citizens in 1285. More than 300,000 soldiers and citizens in 1287[citation needed] Dai Viet more than 200.000-300.000 people in 1285 ; Champa about 60.000 people[citation needed] Casualties and losses More than 60.000 killed and hundreds of thousands captured[citation needed] More than 50.000-100.000 killed[citation needed] - Central Asia (Khwarizm)

- Georgia and Armenia

- Volga Bulgaria (Samara Bend

- Bilär)

- Anatolia

- Europe (Dzurdzuketia

- Rus'

- Poland

- Hungary)

- Tibet

- Baghdad

- Korea

- India

- Japan (Bun'ei

- Kōan)

- Vietnam (Bạch Đằng)

- China (Jin

- Song)

- Burma (Ngasaunggyan

- Pagan

- Bhamo)

- Java

- Syria

- Palestine (Ain Jalut)

Mongol invasions of Vietnam or Mongol-Vietnamese War refer to the three times that the Mongol Empire and its chief khanate the Yuan Dynasty invaded Đại Việt during the Trần Dynasty and the Kingdom of Champa: in 1257–1258, 1284–1285, and 1287–1288. The Mongols were defeated by Đại Việt and were forced to withdraw their troops from Đại Việt and Champa[1]. However, the Dai Viet and Champa became tributary states of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty.[2]

Contents

Background

By 1250, the Mongols controlled most of Eurasia including Eastern Europe, North China, Central Asia, Manchuria, Turkey, Tibet and Iran. At the same time the Koreans revolted against the rule of the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire though the Goryeo court accepted the demand of submission.

Mongke Khan (r. 1251–59) planned to attack Song China from three directions in 1256. Therefore, he ordered the prince Kublai to pacify the Dali Kingdom. After subjugating the Dali, Kublai sent one column under Uriyankhadai to south. Uriyankhadai sent envoys to ask the Vietnamese a route to attack Southern Song Dynasty. But the Tran Vietnamese imprisoned Mongol envoys.[3] This action led Uriyankhadai and his son Aju to invade Đại Việt with 3,000 Mongols and 10,000 Yi tribesmen.[3]

The first sack of Thăng Long (Hanoi)

In 1257, a Mongol column under Uriyankhadai, the son of Subotai, invaded Đại Việt, routing the Vietnamese militants and sacking the capital at Thăng Long (renamed Hà Nội in 1831). He executed its inhabitants for the murder of the envoys. Uriyankhadai's troops suffered from disease, heat and guerrilla warfare. Uriyankhadai withdrew when the Trần Emperor accepted Mongol overlordship.[4] The king Trần Thái Tông paid tribute to Uriyankhadi who had quickly evacuated Đại Việt. Peace lasted until the Mongol invasion in 1280's.

When Kublai became the Great Khan, the relationship between the two nations was in good shape. According to the history of the Yuan Dynasty, the Trần court sent tribute every three years and received a darughachi. By 1266, however, a standoff developed, as the King Thánh Tông sought to a loose tributary relationship. While Kublai demanded full submission, Thánh Tông sent official letter strongly requiring Kublai to take his darughachi back. Because of the civil war of the Mongol Empire and the conquest of China, armed conflict was delayed. Instead Kublai reminded him of the peace treaty signed by the Mongols and Đại Việt.

By 1278–79, the Mongol troops stationed along Đại Việt's borders. The Trầns' new ruler Nhân Tông resisted renewed Mongol demands for personal attendance at Kublai's court but dispatched his uncle Tran Di Ai as envoy. Kublai tried to enthrone Di Ai as prince in 1281 but Di Ai and his small army were ambushed by Đại Việt forces.

Champa

Sogetu of the Jalayir, the governor of Canton, was dispatched to demand full-submission of Champa. Although, the king of Champa accepted the Mongol protectorate[5], his subjects strongly ignored it. In 1282, Sogetu led a maritime invasion of Champa with 5,000 men, but could only muster 100 ships because most of the Yuan dynasty's ships had been lost in the invasions of Japan.[6] However, Sogetu was successful in capturing Vijaya, the Champa capital later that year. The aged Champa king Indravarman V retreated out of the capital, avoiding Mongol attempts to capture him in the hills. His son would wage a guerilla war with the Mongols for the next few years, eventually wearing down the invaders.[7] Stymied by the withdrawal of the Champa king, Sogetu asked reinforcements from Kublai but sailed home in 1284, just as another Mongol fleets with more than 15,000 troops under Ataqai and Arikhgiya reembarked on a fruitless mission to reinforce him. Sogetu presented his plan to have more troops come over through Đại Việt, because he believed the Tran was a Mongol vassal. Kublai liked the idea and put his son Toghan, in command, with Sogetu in second command.

Mongol wars 1284-88

In 1284 Kublai appointed his son Toghan (tiếng Việt: Thoát Hoan) to conquer Champa. Toghan demanded from the Tran a route to Champa, which would trap the Champan army from both north and south. While Nhân Tông preferred the surrender, General Hưng Đạo rallied 15,000 troops and refused to help the Mongols by providing a route and supplies. However, Toghan defeated Hung Dao's army and reoccupied Thăng Long in June, 1285. Drawing from experience with previous Chinese invasions, the Đại Việt royal family abandoned the capital, and retreated south, while enacting a scorched earth campaign by burning villages and crops.[7] At the same time, Sogetu moved his army up north in an attempt to envelop Đại Việt in a pincer movement.[7] The Cham were in hot pursuit of Sogetu, however, and managed to kill Sogetu and defeat his army while it was moving north.[8] As the Yuan forces advanced down the Red River, dispersing their power, General Quang Khải counterattacked them at Chương Dương, forcing Toghan to withdraw. Toghan returned without a huge loss of the army under him thanks to Kypchak officer Sidor and his navy. Seeing the Mongol force weakened under the Vietnamese heat and sickness, Trần Hưng Đạo took this opportunity to strike, selecting battlefields where the Mongol cavalry could not be fully employed.[8] The Mongol forces under Sogetu and Li Heng (tiếng Việt: Lí Hằng) suffered a major defeat on the muddy grounds of the Red River. The Yuan army retreated north, but few made it back to China due to constant harassment by Đại Việt troops and fighters from the Hmong and Yao peoples.[8]

The next year Kublai installed Nhân Tông's younger brother Trần Ích Tắc, a defector to the Yuan, as prince of Đại Việt. But hardship in the Yuan's Hunan supply base aborted his plan.

The third Mongol invasion was also defeated by the Đại Việt forces under the leadership of General, later Prince Trần Hưng Đạo. In 1287 Toghan invaded with 70,000 regular troops, 21,000 tribal auxiliaries from Yunnan and Hainan, a 1,000-man vanguard under Abachi, and 500 ships under the Muslim Omar (tiếng Việt: Ô Mã Nhi) and Chinese Fanji (according to some sources, the Mongol force was composed of 300,000–500,000 men). Kublai sent the veterans such as Arikhgiya, Nasir al-Din and his grandson Esen-Temur. The strategy of this invasion was different: a huge base was to be established just inland from Hải Phòng, and a large-scale naval assault mounted as well as a land attack. Trần Hưng Đạo withdrew from inhabited areas, leaving the Mongols with nothing to conquer. 500 vessels were prepared to bring provisions to Toghan's army. Borrowing a tactic used by general, later Emperor Ngô Quyền in 938 to defeat an invading Chinese fleet, the Đại Việt forces drove iron-tipped stakes into the bed of the Bạch Đằng River, and then, with a small flotilla, lured the Mongol fleet into the river just as the tide was starting to ebb. Trapped or impaled by the iron-tipped stakes (some of which have been recently recovered and now being displayed in a Hanoi museum), the entire Mongol fleet of 400 craft was sunk, captured, or burned by fire arrows. This would later become known as the Battle of Bạch Đằng. Caught between the Champa and Đại Việt, Sogetu lost his life. The Mongol army retreated to China, harassed en-route by Trần Hưng Đạo's troops. The Yuan officers such as Abachi and Fanji died in bloody retreat and Omar was captured.

Aftermath in Đại Việt

Trần Hưng Đạo on South Vietnamese banknote

Trần Hưng Đạo on South Vietnamese banknote

Kublai angrily banished Toghan to Yangzhou for life. The Mongols and the Tran Vietnamese agreed to exchange their war prisoners. While Nhan Tong was willing to pay tribute to the Yuan, relations again foundered on the question of attendance at the Mongol court and hostile relations continued.

The Trần Dynasty decided to accept Mongol supremacy in order to avoid further conflicts. Tran Nhon Tong acknowledged himself Kublai's vassal in late 1288.[5] Because he refused to come in person, Kublai detained his envoy, Dao-tu Ki, in 1293. Kublai's successor Temur Khan (r.1294-1307), finally released all detained envoys, settling for a tributary relationship, which continued to the end of the Mongol Empire.

Aftermath in Champa

The Champa Kingdom decided to accept Mongol supremacy. A tributary relationship, which continued for the life of the Mongol Empire. The king of Champa made the act of vassalage to the Mongols.

Notes

- ^ a b Cima, Ronald. (1987). Vietnam: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress.

- ^ Tansen Sen - The Yuan Khanate and India Cross-Cultural Diplomacy in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries, pp. 305

- ^ a b Atwood, C. (2004) p. 579

- ^ Connolly, P. (1998) p. 332

- ^ a b Grousset, R. (1970) p. 290

- ^ Delgado, J. (2008) p. 158

- ^ a b c Delgado, J. (2008) p. 159

- ^ a b c Delgado, J. (2008) p. 160

References

- Atwood, Christopher Pratt. (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York: Facts of File. ISBN 978-0816046713.

- Connolly, Peter. (1998). The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare. Routledge. ISBN 978-1579581169.

- Delgado, James P. (2008). Khubilai Khan's Lost Fleet: In Search of a Legendary Armada. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-0520259768.

- Grousset, René. (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0813513041.

See also

- Kingdom of Champa

- Battle of Bạch Đằng (1288)

- Tran Hung Dao

- Mongol Empire

- Yuan Dynasty

- Kublai Khan

- Mongol invasions

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.Categories:

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.Categories:- 13th-century conflicts

- Invasions

- Wars involving Vietnam

- Wars involving the Mongols

- Yuan Dynasty

- Mongol Empire

- History of Mongolia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.