- Mongol invasions of Tibet

-

Mongol conquest of Tibet Date 13th century Location Tibet Result Capitulation of Tibet, Tibet under Mongol administrative rule. Belligerents Tibet Mongol Empire - Central Asia (Khwarizm)

- Georgia and Armenia

- Volga Bulgaria (Samara Bend

- Bilär)

- Anatolia

- Europe (Dzurdzuketia

- Rus'

- Poland

- Hungary)

- Tibet

- Baghdad

- Korea

- India

- Japan (Bun'ei

- Kōan)

- Vietnam (Bạch Đằng)

- China (Jin

- Song)

- Burma (Ngasaunggyan

- Pagan

- Bhamo)

- Java

- Syria

- Palestine (Ain Jalut)

The Mongol invasion of Tibet can refer to the following campaigns by the Mongols against Tibet. The earliest is the alleged plot to invade Tibet by Genghis Khan in 1206[1], which is considered anachronistic; there is no evidence of Mongol-Tibetan encounters prior to the military campaign in 1240[2]. The first confirmed campaign is the invasion of Tibet by the Mongol general Doorda Darkhan in 1240,[3] a campaign of 30,000 troops[4][5] that resulted in 500 casualties[6]. The campaign was smaller than the full-scale invasions used by the Mongols against large empires. The purpose of this attack is unclear, and is still in debate among tibetologists.[7]

Contents

Invasion

Prior to 1240

According to one traditional Tibetan account, the Mongol emperor Genghis Khan plotted to invade Tibet in 1206, but was dissuaded when the Tibetans promised to pay tribute to the Mongols.[8] Modern scholars consider the account to be anachronistic and factually wrong.[9] Genghis' campaign was targeted at the Tangut kingdom of Xixia, not Tibet, and there was certainly no tribute being paid to the Mongols prior to 1240.[10] There is no evidence of interaction between the two nations prior to Doorda Darkhan's invasion in 1240.[11]

The earliest real Mongol contact with ethnic Tibetan people came in 1236, when a Tibetan chief near Wenxian submitted to the Mongols campaigning against the Jin Dynasty in Sichuan.

1240

Doorda Darkhan's Tibetan campaign Date 1240 Location Tibet Result Mongols withdrew. All Mongol generals were called back to Mongolia to appoint a successor to Ogedai Khan. Belligerents Mongol Empire Tibet Commanders and leaders Doorda Darkhan Leaders of the Rwa-sgreng monastery Strength 30,000 soldiers Unknown Casualties and losses Minimal (or no loss) 500 In 1240, the Mongol Prince Köten (Godan), Ogedei's son and Guyuk's younger brother, "delegated the command of the Tibetan invasion to the Tangut[12] general, Doorda Darqan (Dor-ta)".[13] The expedition was "the first instance of military conflict between the two nations".[14] The attack consisted of 30,000 men (most possibly much smaller than that)[15][16] and resulted in 500 casualties[17], along with the burning of the Kadampa monasteries of Rwa-sgreṅ and Rgyal-lha-khang.[18] The campaign was smaller than the full-scale invasions used by the Mongols against large empires. According to Turrell V. Wylie, that much is in agreement among tibetologists. However, the purpose of invasion is disputed among Tibetan scholars, partly because of the abundance of anachronistic and factually erroneous sources.[19]

However, modern studies find that the Mongol scouts burned Rwa-sgreng only.[20] The bKa’-brgyud-pa monasteries of sTag-lung and ’Bri-gung, with their old link to the Xixia dynasty, were spared because Doorda himself was a Tangut Buddhist.[21] The ’Bri-gung abbot suggested the Mongols invite the Sa-skya-pa hierarch, Sa-skya Pandita. After he met Köten, Sa-skya Pandita died there leaving his two nephews. Sa-skya Pandita convinced other monasteries in Central Tibet to align with the Mongols. The Mongols kept them as hostages referring symbolic surrender of Tibet.[22]

One view, considered the most traditional, is that the attack was a retaliation on Tibet caused by the Tibetan refusal to pay tribute.[23] Wylie points out that the Tibetans stopped paying tribute in 1227, while Doorda Darkhan's invasion was in 1240, suggesting that the Mongols, not known for their empathy, would not wait over a decade to respond. The text from which this claim is based on also makes other anachronistic mistakes, insisting that Genghis was planning to attack Tibet prior to Doorda Darkhan's invasion, when the real campaign was against the Tangut kingdom of Xixia.[24]

Another theory, supported by Wylie, is that the military action was a reconnaissance campaign meant to evaluate the political situation in Tibet.[25] The Mongols hoped to find a single monarch with whom they could threaten into submission, but instead found a Tibet that was religiously and politically divided, without a central government.[26]

A third view is that the troops were sent as raids and "looting parties", and that the goal of the campaign was to pillage the "wealth amassed in the Tibetan monasteries". [27] This is disputed, as the Mongols deliberately avoided attacking certain monasteries, a questionable decision if their only goal was profit.[28]

Whatever the purpose of the invasion, the Mongols withdrew in 1241, as all the Mongol princes were recalled back to Mongolia in preparation for the appointment of a successor to Ogedai Khan.[29] In 1244, the Mongols returned to Tibet. They invited a Tibetan lama, Sakya Pandita, to Godan's camp, where he agreed to capitulate Tibet, after the Mongols threatened a full-scale invasion of the region.

Putative invasion under Mongke Khan

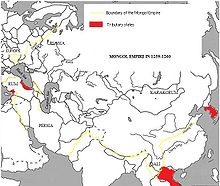

The Mongol Empire in 1259.

Sakya Pandita died in 1251 and his master Köten possibly died at the same time, and Möngke Khan became Khagan in the same year. Some sources say there was a Mongolian invasion in 1251, in retribution for a failure to pay tribute, or in 1251-2 'to take formal possession of the country'. In order to strengthen his control over Tibet, Mongke made Qoridai commander of the Mongol and Han troops in Tufan in 1251. Two attacks are mentioned, one led by Dörbetei, the other by Qoridai, and the double campaign struck fear into the Tibetans.[30] Tibetan sources however only mention an attack on a place called Bod kyi-mon-mkhar-mgpon-po-gdong,. Wyle is sceptical however of all of these sources, arguing that the lack of substantive evidence for an invasion raises doubts about the extent of Mongol movements in Tibet proper.'[31] He concludes:-

-

'Excluding the 1252 attack against the unidentified Mon-mkmar-mgon-po-gdong mentioned earlier, there seems to be no evidence to prove the presence of Mongol troops in central Tibet during the two decades that 'Phags-pa Lama was away from Sa-skya (1244-65). During those years, external campaigns of conquest and internal feuds between scions of the sons of Chinggis Khan occupied the attention of the Mongols. Tibet, whose formidable terrain was politically fragmented by local lords and lamas, posed no military thereat to the Mongols, and it was all but ignored by them.'[32]

In 1252-53 Qoridai invaded Tibet, reaching as far as Damxung. The Central Tibetian monasteries submitted to the Mongols. Mongke divided between his relatives as their appanages in accordance with Great Jasag of Genghis Khan. Many Mongol aristocrats including Khagan himself seem to have sought blessings of prominent Tibetan lamas. Möngke Khan patronized Karma Baqshi (1204–83) of the Karma-pa suborder and the ’Bri-gung Monastery, while Hulegu, khan of the Mongols in the Middle East, sent lavish gifts to both ’Bri-gung and the Phag-mo-gru-pa suborder’s gDan-sa-thel monastery. Later William Rubruck report that he saw Chinese, Tibetan, and Indian Buddhist monks at the capital city, Karakourm, of the Mongol Empire.

Although, Karma of the Karma-pa sect politely refused to stay with him preferring his brother: the Khagan, in 1253 Prince Kubilai summoned to his court the Sa-skya-pa hierarch’s two nephews, Blo-gros rGyal-mtshan, known as ’Phags-Pa lama (1235–80), and Phyag-na rDo-rje (d. 1267) from the late Köten's ordo in Liangzhou. Khubilai Khan first met 'Phags-pa lama in 1253, presumably to bring the Sa-skya lama who resided in Köden's domain, and who was a symbol of Tibetan surrender, to his own camp.[33] At first Kublai remained shamanist, but his chief khatun, Chabui (Chabi), converted to Buddhism and influenced Kublai's religious view. During Kublai's expedition into Yunnan, his number two, Uriyangkhadai, had to station in Tibet in 1254-55 possibly to supress war-like different tribes in Tibet.

In 1265 Qongridar ravaged the Tufan/mDo-smad area, and from 1264 to 1275 several campaigns pacified the Tibetan and Yi peoples of Xifan around modern Xichang. By 1278 Mongol myriarchies: tumens and postroads reached through mDo-khams as far west as Litang.

Aftermath

Main article: Tibet under Yuan administrative ruleTibet was incorporated into the Mongol Empire under Mongolian administrative rule[34], but the region was granted with a degree of political autonomy. Kublai Khan would later include Tibet into his Yuan Dynasty, and the region remained administratively separate from the conquered provinces of Song Dynasty China.

According to the Tibetan traditional view, the khan and the lama established "priest-patron" relations. This meant administrative management and military assistance from the khan and assistance from the lama in spiritual issues. Tibet was conquered by the Mongols before the Mongol invasion of South China.[35] After the conquest of the Song Dynasty, Kublai Khan consolidated Tibet into the new Yuan Dynasty, but Tibet was ruled under the Xuanzheng Yuan, separate from the Chinese provinces. The Mongols granted the Sakya lama a degree political authority, but retained control over the administration and military of the region.[36] As efforts to rule both territories while preserving Mongol identity, Kublai Khan prohibited Mongols from marrying Chinese, but left both the Chinese and Tibetan legal and administrative systems intact.[37] Though most government institutions established by Kublai Khan in his court resembled the ones in earlier Chinese dynasties,[38] Tibet never adopted the imperial examinations or Neo-Confucian policies.

Towards the end of the Yuan Dynasty, Tibet regained its independence from the Mongols with the decline of the Yuan.

Notes

- ^ Wylie. p.105

- ^ Wylie. p.106

- ^ Wylie. p.110, 'delegated the command of the Tibetan invasion to an otherwise unknown general, Doorda Darkhan'.

- ^ Shakabpa. p.61: 'thirty thousand troops, under the command of Leje and Dorta, reached Phanpo, north of Lhasa.'

- ^ Sanders. p. 309, his grandson Godan Khan invaded Tibet with 30000 men and destroyed several Buddhist monasteries north of Lhasa

- ^ Wylie. p.104

- ^ Wylie. p.103

- ^ Wylie. p.105: 'Why would Chinggis plan an invasion of Tibet as soon as he became Khan of the Mongols in 1206.'

- ^ Wylie. p.107, 'the statement that the 1240 expedition was a punitive raid for failure to pay tribute is without foundation.'

- ^ Wylie. p.106, '...erred in identifying Tibet as the country against Chinggis launched that early campaign. His military objective was the Tangut kingdom of Hsi-hsia.'

- ^ Wylie. p.106, 'the first instance of military conflict between the two nations'

- ^ C.P.Atwood - Encyclopedia of Mongolia and Mongol Empire, p.538

- ^ Wylie. p.110.

- ^ Wylie. p.106

- ^ Shakabpa. p.61: 'thirty thousand troops, under the command of Leje and Dorta, reached Phanpo, north of Lhasa.'

- ^ Sanders. p. 309, his grandson Godan Khan invaded Tibet with 30000 men and destroyed several Buddhist monasteries north of Lhasa

- ^ Wylie. p.104

- ^ Wylie. p.104

- ^ Wylie. p.103

- ^ Turrel J.Wylie-The First Mongol Conquest of Tibet Reinterpreted, pp.110

- ^ C.P.Atwood - Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire, p.538

- ^ Wylie. p.112

- ^ Wylie. p.106

- ^ Wylie. p.106

- ^ Wylie. p.110

- ^ Wylie. p.110

- ^ Kwanten. p. 74

- ^ Wylie. p.107

- ^ Wylie. p.111

- ^ Petech 2003 p.342.

- ^ Wylie, ibid.p.323: 'it is suggested here that references in Chinese sources pertain to campaigns in peripheral areas and that there was no Mongol invasion of central Tibet at that time.'

- ^ Wylie, ibid. p.326.

- ^ Wylie p.323-324.

- ^ Wylie. p.104: 'To counterbalance the political power of the lama, Khubilai appointed civil administrators at the Sa-skya to supervise the mongol regency.'

- ^ Laird 2006, pp. 114-117

- ^ Dawa Norbu. China's Tibet Policy, pp. 139. Psychology Press.

- ^ Schirokauer, Conrad. A Brief History of Chinese Civilization. Thomson Wadsworth, (c)2006, p 174

- ^ Rossabi, M. Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times, p56

References

- Laird, Thomas. The Story of Tibet: Conversations with the Dalai Lama (2006) Grove Press. ISBN 0802118275

- Rossabi, Morris. China Among Equals: The Middle Kingdom and Its Neighbors, 10th-14th Centuries (1983) Univ. of California Press. ISBN 0520043839

- Sanders, Alan J. K. Historical dictionary of Mongolia (2003) Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810844346

- Saunders, John Joseph. The history of the Mongol conquests. (2001) University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0812217667

- Shakabpa, W.D. Tibet: A Political History. (1967) Yale University Press. ISBN 0961147415

- Smith, Warren W., Jr. Tibetan Nation: A History Of Tibetan Nationalism And Sino-tibetan Relations (1997) Westview press. ISBN 978-0813332802

Tibet Autonomous Region Topics Admin.

divisionsLhasa | Chengguan District · Lhünzhub County · Damxung County · Nyêmo County · Qüxü County · Doilungdêqên County · Dagzê County · Maizhokunggar County

Nagqu | Nagchu County · Lhari County · Biru County · Nyainrong County · Amdo County · Xainza County · Sog County · Baingoin County · Baqên County · Nyima County · Shuanghu Special District*

Qamdo | Qamdo County · Jomda County · Gonjo County · Riwoqê County · Dêngqên County · Zhag'yab County · Baxoi County · Zogang County · Markam County · Lhorong County · Banbar County

Nyingchi | Nyingchi County · Gongbo'gyamda County · Mainling County** · Mêdog County** · Bomê County · Zayü County** · Nang County**

Shannan | Nêdong County · Zhanang County · Gonggar County · Sangri County · Qonggyai County · Qusum County · Comai County · Lhozhag County · Gyaca County · Lhünzê County** · Cuona County** · Nagarzê County

Xigazê | Xigazê City · Namling County · Gyangzê County · Tingri County · Sa'gya County · Lhazê County · Ngamring County · Xaitongmoin County · Bainang County · Rinbung County · Kangmar County · Dinggyê County · Zhongba County · Yadong County · Gyirong County · Nyalam County · Saga County · Gamba County

Ngari | Gar County · Burang County · Zanda County · Rutog County · Gê'gyai County · Gêrzê County · Coqên County■ = Prefecture-level city ■ = Prefecture

* Not an official division ** Part of the South Tibet area, which is administered by India and claimed by the PRC.Culture Society Others History of Asia Sovereign

states- Afghanistan

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- Bhutan

- Brunei

- Burma (Myanmar)

- Cambodia

- People's Republic of China

- Cyprus

- East Timor (Timor-Leste)

- Egypt

- Georgia

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Israel

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- North Korea

- South Korea

- Kuwait

- Kyrgyzstan

- Laos

- Lebanon

- Malaysia

- Maldives

- Mongolia

- Nepal

- Oman

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Qatar

- Russia

- Saudi Arabia

- Singapore

- Sri Lanka

- Syria

- Tajikistan

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

- Uzbekistan

- Vietnam

- Yemen

States with limited

recognition- Abkhazia

- Nagorno-Karabakh

- Northern Cyprus

- Palestine

- Republic of China (Taiwan)

- South Ossetia

Dependencies and

other territoriesCategories:- Military history of Tibet

- Mongol invasions

- 13th-century conflicts

- 13th century in Asia

- Wars involving the Mongols

- History of Mongolia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.