- Colchicine

-

Colchicine

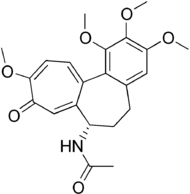

Systematic (IUPAC) name N-[(7S)-1,2,3,10-tetramethoxy-9-oxo-5,6,7,9-tetrahydrobenzo[a]heptalen-7-yl]acetamide Clinical data AHFS/Drugs.com monograph MedlinePlus a682711 Pregnancy cat. X Legal status RX/POM Routes Oral tablets Pharmacokinetic data Half-life 9.3 - 10.6 hours Excretion Primarily feces, urine 10-20% Identifiers CAS number 64-86-8

ATC code M04AC01 PubChem CID 6167 IUPHAR ligand 2367 DrugBank DB01394 ChemSpider 5933

UNII SML2Y3J35T

KEGG D00570

ChEBI CHEBI:27882

ChEMBL CHEMBL107

Chemical data Formula C22H25NO6 Mol. mass 399.437 SMILES eMolecules & PubChem  (what is this?) (verify)

(what is this?) (verify)Colchicine is a medication used for gout. It is a toxic natural product and secondary metabolite, originally extracted from plants of the genus Colchicum (autumn crocus, Colchicum autumnale, also known as "meadow saffron"). It was used originally to treat rheumatic complaints, especially gout, and still finds use for these purposes today despite dosing issues concerning its toxicity.[1] It was also prescribed for its cathartic and emetic effects. Colchicine's present medicinal use is in the treatment of gout, familial Mediterranean fever, pericarditis and Behçet's disease. It is also being investigated for its use as an anti-cancer drug.

Oral colchicine has been used for many years as an unapproved drug with no prescribing information, dosage recommendations, or drug interaction warnings approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).[2] On July 30, 2009 the FDA approved colchicine as a monotherapy for the treatment of familial Mediterranean fever and acute gout flares,[2] and gave 7-year marketing exclusivity[3] to URL Pharma, in exchange for URL Pharma doing 2 new studies. URL Pharma raised the price from $0.09 per pill to $4.85, and sued to remove other versions from market. Colchicine in combination with probenecid has been FDA approved prior to 1982.[3]

Contents

History

The plant source of colchicine, the autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale), was described for treatment of rheumatism and swelling in the Ebers Papyrus (ca. 1500 B.C.), an Egyptian medical papyrus.[4] The use of the bulb-like corms of Colchicum for gout probably traces back to ca. 550 A.D., as the "hermodactyl" recommended by Alexander of Tralles. Colchicum extract was first described as a treatment for gout in De Materia Medica by Pedanius Dioscorides in the first century CE. Colchicum corms were used by the Persian physician ibn Sina (Avicenna) and other Islamic physicians, were recommended by Ambroise Pare in the sixteenth century, and appeared in the London Pharmacopoeia of 1618.[5] Colchicum plants were brought to America by Benjamin Franklin, who suffered from gout himself and had written humorous doggerel about the disease during his stint as Envoy to France.[6]

Colchicine was first isolated in 1820 by the French chemists P.S. Pelletier and J. Caventon.[7] In 1833, P.L. Geiger purified an active ingredient, which he named colchicine.[8] The chemical was later[when?] identified as a tricyclic alkaloid, and its pain-relieving and anti-inflammatory effects for gout were linked to its ability to bind with tubulin.

Pharmacology

Biological function

Colchicine inhibits microtubule polymerization by binding to tubulin, one of the main constituents of microtubules. Availability of tubulin is essential to mitosis, and therefore colchicine effectively functions as a "mitotic poison" or spindle poison.[9] Since one of the defining characteristics of cancer cells is a significantly increased rate of mitosis, this means that cancer cells are significantly more vulnerable to colchicine poisoning than are normal cells. However, the therapeutic value of colchicine against cancer is (as is typical with chemotherapy agents) limited by its toxicity against normal cells.

The mitosis inhibiting function of colchicine has been of great use in the study of cellular genetics. To see the chromosomes of a cell under a light microscope, it is important that they be viewed near the point in the cell cycle in which they are most dense. This occurs near the middle of mitosis, so mitosis must be stopped before it completes. Adding colchicine to a culture during mitosis is part of the standard procedure for doing karyotype studies.

Apart from inhibiting mitosis (a process heavily dependent on cytoskeletal changes), colchicine also inhibits neutrophil motility and activity, leading to a net anti-inflammatory effect.

Indications

Colchicine has a relatively low therapeutic index.

In August 2009, colchicine won Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in the United States as a stand-alone drug for the treatment of acute flares of gout and familial Mediterranean fever.[10][11] It had previously been approved as an ingredient in an FDA-approved combination product for gout. The approval was based on a study in which two doses an hour apart were effective at combating the condition.[10]

It is also used as an anti-inflammatory agent for long-term treatment of Behçet's disease.[12]

Off-label uses

The British drug development company Angiogene is developing a prodrug of a colchicine congener, ZD6126[13] (also known as ANG453) as a treatment for cancer.

Colchicine is "used widely" off-label by naturopaths for a number of treatments, including the treatment of back pain.[14]

Contraindications

Long term (prophylactic) regimens of oral colchicine are absolutely contraindicated in patients with advanced renal failure (including those on dialysis). 10-20% of a colchicine dose is excreted unchanged by the kidneys. Colchicine is not removed by hemodialysis. Cumulative toxicity is a high probability in this clinical setting. A severe neuromyopathy may result. The presentation includes a progressive onset of proximal weakness, elevated creatine kinase, and sensorimotor polyneuropathy. Colchicine toxicity can be potentiated by the concomitant use of cholesterol lowering drugs (statins, fibrates). This neuromuscular condition can be irreversible (even after drug discontinuation). Accompanying dementia has been noted in advanced cases. It may culminate in hypercapnic respiratory failure and death. (Minniti-2005)

Side effects

Side effects include gastrointestinal upset and neutropenia. High doses can also damage bone marrow and lead to anemia. Note that all of these side effects can result from hyperinhibition of mitosis.[citation needed]

A main side effect associated with all mitotic inhibitors is peripheral neuropathy which is a numbness or tingling in the hands and feet due to peripheral nerve damage which can becomes so severe that reduction in dosage or complete cessation of the drug may be required. Microtubules are involved in vesicular transport. In normal cells, Brownian motion sets the stage for the vesicles to reach their destination. Peripheral nerves are among the longest in the body. Brownian motion is not significant enough in these peripheral nerves to allow vesicles to reach their destination. Thus, they are susceptible to microtubule toxins.[citation needed]

Toxicity

Colchicine poisoning has been compared to arsenic poisoning; symptoms start 2 to 5 hours after the toxic dose has been ingested and include burning in the mouth and throat, fever, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain and kidney failure. These symptoms may set in as many as 24 hours after the exposure. Onset of multiple-system organ failure may occur within 24 to 72 hours. This includes hypovolemic shock due to extreme vascular damage and fluid loss through the GI tract, which may result in death. Additionally, sufferers may experience kidney damage resulting in low urine output and bloody urine; low white blood cell counts (persisting for several days); anemia; muscular weakness; and respiratory failure. Recovery may begin within 6 to 8 days. There is no specific antidote for colchicine, although various treatments do exist.[15]

Certain common inhibitors of CYP3A4 and/or P-gp, including grapefruit juice, may increase the risk of colchicine toxicity.[1]

Biosynthesis

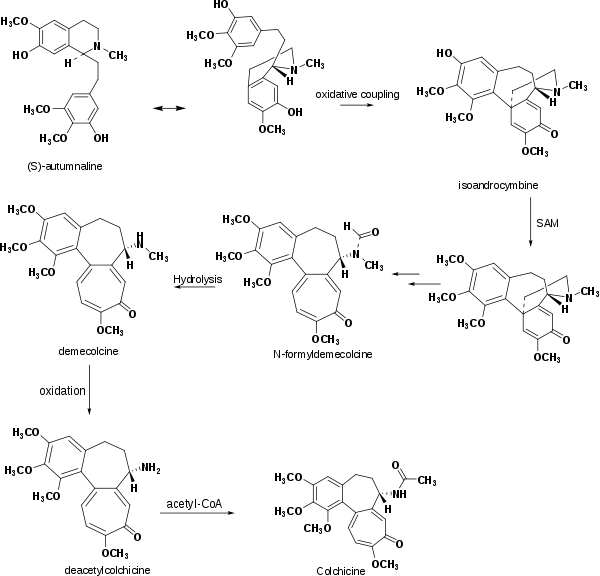

Several experiments have shown that the biosynthesis of colchicine involves the amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine as precursors. Indeed, the feeding of Colchicum autumnale with radioactive amino acid, tyrosine-2-C14, caused the latter to be partially incorporated in the ring system of colchicine. The induced absorption of radioactive phenylalanine-2-C14 by Colchicum byzantinum, another plant of the Colchicaceae family, resulted in its efficient absorption by colchicine.[16] However, it was proven that the tropolone ring of colchicine resulted essentially from the expansion of the tyrosine ring. Further radioactive feeding experiments of Colchicum autumnale revealed that Colchicine can be synthesized biosynthetically from (S)-Autumnaline. That biosynthesic pathway occurs primarily through a para-para phenolic coupling reaction involving the intermediate isoandrocymbine. The resulting molecule undergoes O-methylation directed by S-Adenosylmethionine (SAM). Two oxidation steps followed by the cleavage of the cyclopropane ring leads to the formation of the tropolone ring contained by N-formyldemecolcine. N-formyldemecolcine hydrolyzes then to generate the molecule demecolcine which also goes through an oxidative demethylation that generates deacetylcolchicine. The molecule of colchicine appears finally after addition of acetyl-Coenzyme A to deacetylcolchicine.,[17][18]

Botanical use

Since chromosome segregation is driven by microtubules, colchicine is also used for inducing polyploidy in plant cells during cellular division by inhibiting chromosome segregation during meiosis; half the resulting gametes therefore contain no chromosomes, while the other half contain double the usual number of chromosomes (i.e., diploid instead of haploid as gametes usually are), and lead to embryos with double the usual number of chromosomes (i.e. tetraploid instead of diploid). While this would be fatal in animal cells, in plant cells it is not only usually well tolerated, but in fact frequently results in plants which are larger, hardier, faster growing, and in general more desirable than the normally diploid parents; for this reason, this type of genetic manipulation is frequently used in breeding plants commercially.

When such a tetraploid plant is crossed with a diploid plant, the triploid offspring will usually be sterile (unable to produce fertile seeds or spores), although many triploids can be propagated vegetatively. Growers of annual triploid plants not readily propagated must buy fresh seed from a supplier each year. Many sterile triploid plants, including some tree and shrubs, are becoming increasingly valued in horticulture and landscaping because they do not become invasive species. In certain species, colchicine-induced triploidy has been used to create "seedless" fruit, such as seedless watermelons (Citrullus lanatus). Since most triploids do not produce pollen themselves, such plants usually require cross-pollination with a diploid parent to induce fruit production.

Colchicine's ability to induce polyploidy can be also exploited to render infertile hybrids fertile, for example in breeding triticale (× Triticosecale) from wheat (Triticum spp.) and rye (Secale cereale). Wheat is typically tetraploid and rye diploid, with their triploid hybrid infertile; treatment of triploid triticale with colchicine gives fertile hexaploid triticale.

When used to induce polyploidy in plants, colchicine cream is usually applied to a growth point of the plant, such as an apical tip, shoot, or sucker. Also, seeds can be presoaked in a colchicine solution before planting. Another way to induce polyploidy is to chop off the tops of plants and carefully examine the regenerating lateral shoots and suckers to see if any look different.[19] If no visual difference is evident, flow cytometry can be used for analysis.

Doubling of plant chromosome numbers also occurs spontaneously in nature, with many familiar plants being fertile polyploids. Natural hybridization between fertile parental plants of different levels of polyploidy can produce new plants at an intermediate level, such as a triploid produced by crossing between a diploid and a tetraploid, or a hexaploid produced by crossing between a diploid and an octoploid.

Marketing exclusivity in the United States

As a drug predating the FDA, colchicine was sold in the United States as a generic drug for many years. In 2009, the FDA approved colchicine for gout flares, awarding Colcrys a three-year term of market exclusivity, prohibiting generic sales, and increasing the price of the drug from $0.09 to $4.85 per pill.[20][21][22]

Numerous consensus guidelines, and previous randomized controlled trials, had concluded that colchicine is effective for acute flares of gouty arthritis. However, as of 2006, the drug was not formally approved by the FDA, owing to the lack of a conclusive randomized control trial (RCT). That year the FDA started their "Unapproved Drugs Initiative", through which they sought more rigorous testing of efficacy and safety of colchicine and other unapproved drugs on the market.[23] In exchange for paying for the costly testing, the FDA gave URL Pharma three years of market exclusivity for its Colcrys brand,[24] under the Hatch-Waxman Act, based in part on URL-funded research in 2007, including pharmacokinetic studies and a randomized control trial with 185 patients with acute gout. URL Pharma also received seven years of market exclusivity for Colcrys in treatment of familial Mediterranean fever, under the Orphan Drug Law. URL Pharma then raised the price per pill from $0.09 to $4.85 and sued to remove other versions from the market, increasing annual costs for the drug to U.S. state Medicaid programs from $1 million to $50 million. (In a similar case, thalidomide was approved in 1998 as an orphan drug for leprosy and in 2006 for multiple myeloma.)[25]

In April 2010, in an editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), A.S. Kesselheim and D.H. Solomon said that the rewards of this legislation are not calibrated to the quality or value of the information produced, that there is no evidence of meaningful improvement to public health, that it would be much less expensive for the FDA or National Institutes of Health to pay for trials themselves on widely available drugs such as colchicine, and that the cost burden falls primarily on patients or their insurers.[25] URL Pharma posted a detailed rebuttal of the NEJM editorial.[26]

In September 2010, the FDA ordered a halt to marketing of unapproved single-ingredient oral colchicine.[27]

References

- ^ a b "Colchicine for acute gout: updated information about dosing and drug interactions". National Prescribing Service. 14 May 2010. http://www.nps.org.au/health_professionals/publications/nps_radar/2010/may_2010/brief_item_colchicine. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- ^ a b "FDA Approves Colchicine With Drug Interaction and Dose Warnings". July 2009. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/706814.

- ^ a b [1] FDA Orange Book; search for colchicine

- ^ Wallace Graham and James B. Roberts (1953). "Intravenous colchicine in the treatment of gouty arthritis". Ann Rheum Dis 12 (1): 16–19. doi:10.1136/ard.12.1.16. PMC 1030428. PMID 13031443. http://ard.bmj.com/content/12/1/16.full.pdf.

- ^ Edward F. Hartung (1954). "History of the Use of Colchicum and related Medicaments in Gout". Ann Rheum Dis 13 (3): 190–200. doi:10.1136/ard.13.3.190. http://ard.bmj.com/content/13/3/190.full.pdf. (free BMJ registration required)

- ^ Manuchair S. Ebadi (2007). Pharmacodynamic basis of herbal medicine. ISBN 9780849370502. http://books.google.com/?id=CMJKgfhCKzIC&pg=PA275&lpg=PA275.

- ^ Pelletier PS, Caventon J. Ann. Chim. Phys. 1820;14:69

- ^ 81. Geiger, P. L. Ann. Chem. Pharm. (later, Liebigs .Vnn.) 7:274. 1833.

- ^ Cyberbotanica: Colchicine

- ^ a b FDA Approves Gout Treatment After Long Years of Use, an August 2009 article from MedPage Today

- ^ Cerquaglia C, Diaco M, Nucera G, La Regina M, Montalto M, Manna R (February 2005). "Pharmacological and clinical basis of treatment of Familial Mediterranean Fever (FMF) with colchicine or analogues: an update". Current drug targets: inflammation and allergy 4 (1): 117–24. doi:10.2174/1568010053622984. PMID 15720245. http://www.bentham-direct.org/pages/content.php?CDTIA/2005/00000004/00000001/0019L.SGM.

- ^ Cocco, Giuseppe; Chu, David C.C.; Pandolfi, Stefano (2010). "Colchicine in clinical medicine. A guide for internists". European Journal of Internal Medicine 21 (6): 503. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2010.09.010. PMID 21111934.

- ^ Description of ZD6126 on US National Cancer Institute website retrieved 26th April 2008

- ^ "Deaths sound an Rx alert", The Portland Tribune, Apr 20, 2007

- ^ Colchicine. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Emergency Response Safety and Health Database, August 22, 2008. Retrieved December 23, 2008.

- ^ Leete, E. The biosynthesis of the alkaloids of Colchicum: The incorporation of phenylalaline-2-C14 into colchicine and demecolcine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1963, 85, 3666-3669.

- ^ Dewick, P. M.(2009).Medicinal Natural Products: A biosynthetic Approach. Wiley. p.360-362.

- ^ Maier, U. H.; Meinhart, H. Z. Colchicine is formed by para para phenol-coupling from autumnaline. Tetrahedron Lett. 1997, 38, 7357-7360.

- ^ Deppe, Carol (1993). Breed Your own Vegetable Varieties. Little, Brown & Company. p.150-151. ISBN 0-316-18104-8

- ^ Kurt R. Karst (2009-10-21). "California Court Denies Preliminary Injunction in Lanham Act Case Concerning Unapproved Colchicine Drugs". http://www.fdalawblog.net/fda_law_blog_hyman_phelps/2009/10/california-court-denies-preliminary-injunction-in-lanham-act-case-concerning-unapproved-colchicine-d.html.

- ^ Harris Meyer (2009-12-29). "The High Price of FDA Approval". Kaiser Health News and the Phil adelphia Inquirer. http://www.kaiserhealthnews.org/Stories/2009/December/29/FDA-approval.aspx.

- ^ Colcrys vs. Unapproved Colchicine Statement from URL Pharma

- ^ "FDA Unapproved Drugs Initiative". http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/EnforcementActivitiesbyFDA/SelectedEnforcementActionsonUnapprovedDrugs/ucm118990.htm.

- ^ "About Colcrys". Colcrys. URL Pharma. http://www.colcrys.com/about-colcrys.htm. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ^ a b Kesselheim AS, Solomon DH (June 2010). "Incentives for drug development--the curious case of colchicine". N. Engl. J. Med. 362 (22): 2045–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1003126. PMID 20393164. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/short/362/22/2045.

- ^ Response from URL Pharma

- ^ "FDA orders halt to marketing of unapproved single-ingredient oral colchicine". 30 Sept 2010. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm227796.htm.

External links

- Feature on colchicine, by Matthew J. Dowd at vcu.edu

- NIOSH Emergency Response Database

- Eugene E. Van Tamelen, Thomas A. Spencer Jr., Duff S. Allen Jr., Roy L. Orvis (1959). "The Total Synthesis of Colchicine". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 81 (23): 6341–6342. doi:10.1021/ja01532a070.

Antigout preparations (M04) Uricosurics primary: Probenecid • Sulfinpyrazone • Benzbromarone • Isobromindione

secondary: Amlodipine • Atorvastatin • Fenofibrate • Guaifenesin • LosartanXanthine oxidase inhibitors purine analogues: Allopurinol# • Oxypurinol • Tisopurine

other: Febuxostat • Inositols (Phytic acid, Myo-inositol)Mitotic inhibitors ColchicineOther M: JNT

anat(h/c, u, t, l)/phys

noco(arth/defr/back/soft)/cong, sysi/epon, injr

proc, drug(M01C, M4)

Categories:- Alkaloids

- Antigout agents

- Microtubule inhibitors

- Phenol ethers

- Ketones

- Acetamides

- Heptalenes

- Tropones

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.