- Nanih Waiya

-

Nanih Waiya Mound And Village

Nanih Waiya mound

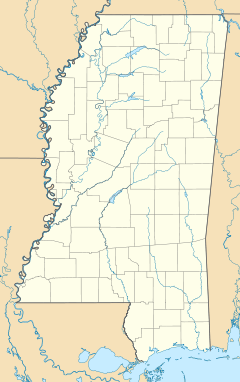

Nanih Waiya moundLocation: Winston County, Mississippi, USA Nearest city: Noxapater, Mississippi Coordinates: 32°55′17″N 88°56′55″W / 32.92139°N 88.94861°WCoordinates: 32°55′17″N 88°56′55″W / 32.92139°N 88.94861°W Governing body: State NRHP Reference#: 73001032 Added to NRHP: March 28, 1973[1] Nanih Waiya (alternately spelled Nunih Waya)[2] is an ancient earthwork mound in Winston County, Mississippi, constructed by indigenous people during the Middle Woodland period, about 0-300 CE. Since the 17th century, the historic Choctaw have venerated Nanih Waiya as their sacred origin location in traditional beliefs.

Today the mound of Nanih Waiya is about 25 feet (7.6 m) tall, 140 feet (43 m) wide, and 220 feet (67 m) long. Evidence suggests that it was originally a platform mound, which has eroded into the present shape. At one time it was bounded on three sides by a circular earthwork enclosure about ten feet tall, which encompassed about a square mile. In 2008 the state of Mississippi returned Nanih Waiya and its associated 150-acre park to the control of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, a federally recognized tribe. Nanih Waiya has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Contents

Archaeological evidence

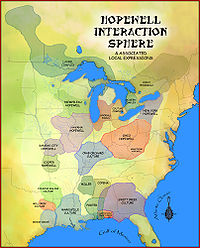

The first archaeological evidence of occupation at Nanih Waiya is dated to 0-300 CE, during the Middle Woodland culture, when it was likely constructed. This made Nanih Waiya contemporaneous with the Hopewell culture, as well as ancient sites such as the Pinson Mounds in Tennessee and Igomar Mound in Mississippi. The dating was based on surface artifacts; no archeological excavation of the mound has been undertaken. Occupation apparently continued at least through 700 CE, the Late Woodland period. Originally the site included a large earthwork circular enclosure on three sides, about ten feet high and encompassing a square mile.[3]

Archaeologists have not documented use by the succeeding Mississippian culture, but generally they suggest that Nanih Waiya has been used for religious purposes throughout its history.[3] The 19th-century naturalist and physician Gideon Lincecum recorded a surviving Choctaw oral history of their coming to the area and constructing the mound. According to tradition, the people had been wandering in the wilderness for 42 Green Corn Festivals, through which they carried the bones of their dead, who numbered more than the living. They found the leaning hill here, where the magical staff indicated they could stay. It was a bountiful land. The council proposed that they build a mound of earth in which respectfully to inter the bones of their ancestors, and so they agreed to do. First they erected a frame of branches, then covered these over, and then added layers of earth, between their domestic tasks, until the mound had reached great size. After they finished, they celebrated with their 43rd Green Corn Festival since they had been in the wilderness. They also said that smaller conical earthen mounds were used for single burials after the first major mound had been built.[4]

The mound has been a site of pilgrimage by the Choctaw since the 17th century, but they have not had any major festivals there. Their religion was more private, and involved rituals related to death and burial, and communication with spirits. Despite the account above, aome anthropologists have noted that, unlike other tribes, the Choctaw did not appear to have practiced the Green Corn ceremony. In the 1850s, observers noted small mounds near Nanih Waiya, but these have apparently been plowed away, and were never dated. They may have been constructed by later Mississippian-culture peoples, or even later Native American groups. As there is neither archaeological data, historical records, nor Choctaw stories of the roles of these small mounds, nothing more may ever be known about them.[3]

Choctaw beliefs

Some Choctaw believe that Nanih Waiya is the "Mother Mound" (Inholitopa iski) where the first Choctaw was created. As told by some Choctaw storytellers, it was either from Nanih Waiya or a cave nearby that the Choctaw people emerged. There are many variations of the story. According to some versions, the mound (or nearby cave) is also the origin of the Chickasaw, Creek people, and possibly even the Cherokee.[3]

Others believe Nanih Waiya is the location where the Choctaw tribe ceased their wanderings and settled after their origin further to the west. George Catlin's Smithsonian Report in 1885 included a story of the Choctaw following a prophet from an origin in the west:

The Choctaws a great many winters ago commenced moving from the country where they then lived, which was a great distance to the west of the great river and the mountains of snow, and they were a great many years on their way. A great medicine man led them the whole way, by going before with a red pole, which he stuck in the ground every night where they encamped. This pole was every morning found leaning to the east, and he told them that they must continue to travel to the east until the pole would stand upright in their encampment, and that there the Great Spirit had directed that they should live.[5]

They say that Nanih Waiya, which means "leaning hill," "stooping hill," or "place of creation" in Choctaw, was the final destination of their migration.

Nanih Waiya: lost and regained

By the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, drawn up September 15-27, 1830, the Choctaw ceded millions of acres of their territory, including Nanih Waiya, to the United States. In the 1840s, the Choctaw Claims Commission of the United States investigated violations of the treaty by U.S. citizens. J.F.H. Claiborne later wrote about the investigations, "Many of the Choctaws examined... regard this mound as the mother, or birth-place of the tribe, and more than one claimant declared that he would not quit the country as long as [Nanih Waiya] remained."[3]

The state of Mississippi preserved Nanih Waiya as a state park for years. It was recognized as a significant site by the federal government, which listed it on the National Register of Historic Places.

In 2006 the Mississippi Legislature State Bill 2803 officially returned control of the site to the Luke Family, of whom T. W. Luke had deeded it to the State with the condition that it be maintained as a park. The 150-acre property reverted back to the Luke family when the State stopped maintaining the park.

In August 2008, the Luke family deeded the mound to the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, a federally recognized tribe, so the Choctaw have regained a sacred place. That November they held a celebration for more than 1,000 people at the mound to mark the occasion.[6] They have declared August 18 as a tribal holiday to mark the return of the mound, and have used the occasion for telling and performances of dances and stories of their origin and history.[7]

Notes

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2009-03-13. http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natreg/docs/All_Data.html.

- ^ Swanton 2001, pg. 25.

- ^ a b c d e Ken Carleton, "Nanih Waiya: Mother Mound of the Choctaw", The Delta Endangered, Spring 1996, Vol.1 (1), NPS Archeology Program, accessed 16 Nov 2009

- ^ Gideon Lincecum, "Choctaw Traditions About Their Settlement in Mississippi and the Origin of Their Mounds", Jackson: Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society, 1904, Vol. 8:521-542

- ^ Catlin, George. Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the year 1885, Part II, Report of the U.S. National Museum under the direction of the Smithsonian Institution for the year 1885. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1886, Annual Report, 40 pt2 : 1-264 and 1-939

- ^ "Feast to celebrate the return of the Nanih Waiya Mound", 14 November 2008, accessed 11 October 2011

- ^ DEBBIE BURT MYERS, "Nanih Waiya Day includes traditional Choctaw dance, food", The Neshoba Democrat, 18 August 2010, accessed 11 October 2011

References

- Catlin, George. Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the year 1885, Part II, ' Report of the U.S. National Museum under the direction of the Smithsonian Institution for the year 1885. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1886, Annual Report, 40 pt2 : 1-264 and 1-939

- Knight, Vernon James, Jr. 1989 "Symbolism of Mississippian Mounds", in Powhatan’s Mantle: Indians in the Colonial Southeast, edited by Peter H. Wood, Gregory A. Waselkov, and M. Thomas Hatley. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press,

- Lincecum, Gideon. (1904) "Choctaw Traditions About Their Settlement in Mississippi and the Origin of Their Mounds", Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society 8:521-542.

- Senate Bill 2803. Mississippi Legislature, 2006 Regular Session. To: Public Property, By: Senator(s) Williamson. AN ACT TO RETURN THE NANIH WAIYA STATE PARK AND MOUND TO THE MISSISSIPPI BAND OF CHOCTAW INDIANS; TO AMEND SECTIONS 29-1-1 AND 55-3-47, MISSISSIPPI CODE OF 1972, TO CONFORM; AND FOR RELATED PURPOSES.

- Swanton, John R. (2001). Source Material for the Social and Ceremonial Life of the Choctaw Indians. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0817311092.

External links

- "State Bill 2803", Mississippi State Website

Choctaw Federally recognized tribes Culture History Nanih Waiya · Chickasaw Campaign of 1736 · Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek · Trail of Tears · Choctaw Capitol Building · Atoka Agreement · Code talkers · Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians v. HolyfieldPolitics and law  Hopewellian peoples

Hopewellian peoplesWoodland period · List of Hopewell sites · Mound builder (people) · List of archaeological periods (North America) Ohio Hopewell Beam Farm · Benham Mound · Cary Village Site · Cedar-Bank Works · Dunns Pond Mound · Ellis Mounds · Ety Enclosure · Ety Habitation Site · Fort Ancient · Fortified Hill Works · Great Hopewell Road · High Banks Works · Hopeton Earthworks · Hopewell Culture National Historical Park · Indian Mound Cemetery · Keiter Mound · Marietta Earthworks · Moorehead Circle · Mound of Pipes · Nettle Lake Mound Group · Newark Earthworks · Oak Mounds · Perin Village Site · Portsmouth Earthworks · Seip Earthworks and Dill Mounds District · Shawnee Lookout · Tremper Mound and Works · Williamson Mound Archeological District

Crab Orchard culture Goodall Focus Goodall Site · Norton Mound GroupHavana Hopewell culture Kansas City Hopewell Marksville culture Miller culture Point Peninsula Complex Swift Creek culture Etowah Indian Mounds · Leake Mounds · Kolomoki Mounds Historic Park · Miner's Creek site, · Nacoochee Mound · Swift Creek mound site · Yearwood siteOther Hopewellian peoples Armstrong culture · Copena culture · Fourche Maline culture · Laurel Complex · Saugeen Complex · Old Stone Fort (Tennessee)Exotic trade items Related topics · Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley · Black drink · burial mound · Calumet (pipe) · Effigy mound · Hopewell pottery · Horned Serpent · Eastern Agricultural Complex · Underwater panther U.S. National Register of Historic Places Topics Lists by states Alabama • Alaska • Arizona • Arkansas • California • Colorado • Connecticut • Delaware • Florida • Georgia • Hawaii • Idaho • Illinois • Indiana • Iowa • Kansas • Kentucky • Louisiana • Maine • Maryland • Massachusetts • Michigan • Minnesota • Mississippi • Missouri • Montana • Nebraska • Nevada • New Hampshire • New Jersey • New Mexico • New York • North Carolina • North Dakota • Ohio • Oklahoma • Oregon • Pennsylvania • Rhode Island • South Carolina • South Dakota • Tennessee • Texas • Utah • Vermont • Virginia • Washington • West Virginia • Wisconsin • WyomingLists by territories Lists by associated states Other  Category:National Register of Historic Places •

Category:National Register of Historic Places •  Portal:National Register of Historic PlacesCategories:

Portal:National Register of Historic PlacesCategories:- Hopewellian peoples

- Archaeological sites in Mississippi

- Choctaw

- Native American history

- National Register of Historic Places in Mississippi

- Protected areas of Winston County, Mississippi

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.