- American badger

-

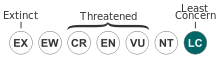

American badgers Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Mustelidae Genus: Taxidea

Waterhouse, 1839Species: T. taxus Binomial name Taxidea taxus

(Schreber, 1778)

American badger range The American badger (Taxidea taxus) is a North American badger, somewhat similar in appearance to the European badger. It is found in the western and central United States, northern Mexico and central Canada, as well as in certain areas of southwestern British Columbia.

Their habitat is typified by open grasslands with available prey (such as mice, squirrels, and groundhogs). They prefer areas with sandy loam soils where they can dig more easily for their prey, such as prairie regions.

In Mexico, this animal is sometimes called "tlalcoyote". The Spanish word for badger is "tejón", but in Mexico this word is also used to describe the coati. This can lead to confusion, for there are both coatis and badgers in Mexico.

Contents

Taxonomy

The American badger is a member of the Mustelidae, a diverse family of carnivorous mammals which also includes the weasel, ferret, and wolverine.[2] The American badger belongs to one of three sub-families of badgers, the other two being the Eurasian badger and the honey badger. The American badger's closest relative is the prehistoric Chamitataxus.

Recognized sub-species include: Taxidea taxus jacksoni, found in the western Great Lakes region; Taxidea taxus jeffersoni, on the west coast of Canada and the US; and Taxidea taxus berlandieri, in the south-western US and in northern Mexico.[3][4] There is considerable overlap in the ranges of subspecies, with intermediate forms occurring in the areas of overlap.

Description

The American badger has most of the general characteristics common to badgers; stocky and low-slung with short, powerful legs, they are identifiable by their huge foreclaws (measuring up to 5 cm in length) and distinctive head markings. Measuring generally between 60 to 75 cm (23.6 to 29.5 inches) in length, males of the species are a little bit larger than females (with an average weight of roughly 7 kg (15.5 pounds) for females and up to almost 9 kg (19.8 pounds) for males). Northern subspecies such as T. t. jeffersonii are heavier than the southern subspecies. In the fall, when food is plentiful, adult male badgers can exceed 11.5 kg (25.3 pounds).[5]

Excluding the head, the American badger is covered with a grizzled, silvery coat of coarse hair or fur. The American badger's triangular face shows a distinctive black and white pattern, with brown or blackish "badges" marking the cheeks and a white stripe extending from the nose to the base of the head. In the subspecies T. t. berlandieri, the white head stripe extends the full length of the body, to the base of the tail.[6]

Food habits

The American badger is a fossorial carnivore. It preys predominantly on pocket gophers (Geomyidae), ground squirrels (Spermophilus), moles (Talpidae), marmots (Marmota), prairie dogs (Cynomys), pika (Ochotona), woodrats (Neotoma), kangaroo rats (Dipodomys), deer mice (Peromyscus), and voles (Microtus), often digging to pursue prey into their dens, and sometimes plugging tunnel entrances with objects.[7] They also prey on ground-nesting birds such as bank swallow or sand martin (Riparia riparia) and burrowing owl (Athene cunicularia), lizards, amphibians, carrion, fish, skunks (Mephitis and Spilogale), insects, including bees and honeycomb and some plant foods such as maize (Zea mais), peas, green beans, mushrooms and other fungi, and sunflower seeds (Helianthus).[4]

Behavior

American badgers are largely nocturnal but have been reported active during the day as well. They do not hibernate, but become less active in winter. A badger may spend much of the winter in cycles of torpor that last around 29 hours. They do emerge from their setts when the temperatures are above freezing.[4]

Badgers sometimes use abandoned burrows of other animals like foxes or animals slightly smaller or bigger. They will sometimes form a mutually beneficial relationship with coyotes. Because coyotes are not very effective at digging rodents out of their burrows, they will chase the animals while they are above ground. Badgers on the other hand are not fast runners, but are well-adapted to digging. When hunting together, they effectively leave little escape for prey in the area.[8]

Major life events

American badger at the Henry Doorly Zoo.

American badger at the Henry Doorly Zoo.

Badgers are normally solitary animals for most of the year, but it is thought that in breeding season they expand their territories to actively seek out mates. Males may breed with more than one female. Mating occurs in late summer and early fall. American badgers experience delayed implantation. Pregnancies are suspended until December or as late as February. Young are born from late March to early April.[4] Litters range from one to five young,[9] averaging about three.[10]

Badgers are born blind, furred, and helpless.[4] Eyes open at 4 to 6 weeks. The female feeds her young solid foods prior to complete weaning, and for a few weeks thereafter.[10] Young American badgers first emerge from the den on their own at 5 to 6 weeks .[9][11] Families usually break up and juveniles disperse from the end of June to August; Messick and Hornocker reported that young American badgers left their mother as early as late May or June.[11] Juvenile dispersal movements are erratic.[9]

Most female American badgers become pregnant for the first time after they are 1 year old. A minority of females 4 to 5 months old ovulate and a few become pregnant. Males usually do not breed until their second year.[4]

Major causes of adult American badger mortality include, in order, automobiles, farmers (by various methods), sport shooting, and fur trapping. Large predators occasionally kill American badgers.[9] Yearly mortality has been estimated at 35% for populations in equilibrium. The average longevity in the wild is 9–10 and the record is 14 years;[12] a captive American badger lived at least 15 years 5 months.[9]

Conservation status

In May 2000, the Canadian Species at Risk Act listed both the American Badger jacksoni subspecies (Taxidea taxus jacksoni) and the jeffersonii subspecies (Taxidea taxus jeffersonii) as an endangered species in Canada.[citation needed] The California Department of Fish and Game (CDFG) designated the American badger as a Species of Special Concern.[13]

Habitat

American badgers occur primarily in grasslands, parklands, farms, and other treeless areas with friable soil and a supply of rodent prey.[14][15] They are also found in forest glades and meadows, marshes, brushy areas, hot deserts, and mountain meadows. American badgers are sometimes found at elevations up to 12,000 feet (3,600 m) but are usually found in the Sonoran and Transition life zones (which are at elevations lower and warmer than those characterized by coniferous forests).[10] In Arizona American badgers occur in desert scrub and semidesert grasslands.[16] In California, American badgers are occasionally found in open chaparral (with less than 50% plant cover) and riparian zones. They are not usually found in mature chaparral.[17] In Manitoba aspen parklands American badger abundance was positively associated with the abundance of Richardson's ground squirrels (Spermophilus richardsonii).[18]

Badgers are one of the few North American carnivores that digs their own burrows and relies on them heavily in their habitat.

American badger use of home range varies with season and sex of the American badger. Different areas of the home range are used more frequently at different seasons and usually are related to prey availability. Males generally have larger home ranges than females. Radio-transmitter tagged American badgers had an average annual home range of 2,100 acres (850 ha). The home range of one female was 1,790 acres (725 ha) in summer, 131 acres (53 ha) in fall, and 5 acres (2 ha) in winter.[19] Lindzey reported average home ranges of 667 to 1,550 acres (270–627 ha).[20]

Estimated density of American badgers in Utah scrub-steppe was 1 per square mile (2.6 km2), or 10 dens per square mile (assuming a single American badger has 10 dens in current or recent use).[4]

The American badger in Ontario, which is part of a particular subspecies, is primarily restricted to the extreme southwestern portion of the province – largely along the north shore of Lake Erie in open areas generally associated with agriculture and woodland edges. There have been a few reports from the Bruce-Grey region. Additionally, although not recently, there have been reports from the southwestern portion of the province, adjacent to the Minnesota border.[21]

Plant communities

American badgers are most commonly found in treeless areas including tallgrass and shortgrass prairies, grass-dominated meadows and fields within forested habitats, and shrub-steppe communities. In the Southwest plant indicators of the Sonoran and Transition life zones (relatively low, dry elevations) commonly associated with American badgers include creosotebush (Larrea tridentata), junipers (Juniperus spp.), Gambel oak (Quercus gambelii), willows (Salix spp.), cottonwoods (Populus spp.), ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa), grasses, and sagebrushes (Artemisia spp.).[10] In Colorado American badgers are common in grass-forb and ponderosa pine habitats.[22] In Kansas American badgers are common in tallgrass prairie dominated by big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), and Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans).[23] In Montana American badgers are present in Glacier National Park in fescue (Festuca spp.) grasslands.[24] In Manitoba, American badgers occur in grassland extensions within aspen (Populus spp.) parklands.[18]

Cover requirements

American badgers enlarge hunting burrows for concealment, protection from weather, and as natal dens; burrows are up to 30 feet (10 m) long and 10 feet (3 m) deep. Large mounds of soil are built up at burrow entrances.[14]

During the summer American badgers usually use a new den each day; holes are usually excavated at least a few days prior to their being used as a den. There was an average of 0.64 dens (in use, signified by an open hole) per acre (1.6/ha) in northern Utah scrub steppe.[20] Where prey is particularly plentiful, American badgers will reuse dens.[10] In the fall American badgers tend to reuse dens, sometimes for a few days at a time. In winter a single den may be used for the majority of the season.[4] Natal dens are dug by the female and are used for extended periods, but litters are often moved several times, probably to allow the mother to forage in new areas close to the nursery. Natal dens are usually larger and more complex than diurnal dens.[9]

Predators

The American badger is an aggressive animal and has few natural enemies. There are reports of predation on smaller individuals by golden eagles (Aquila chrysaetos), coyotes,[4] cougar (Felis concolor), and bobcats (Lynx rufus).[25] Bears (Ursus spp.) and gray wolf (Canis lupus) occasionally kill American badger.[9]

See also

- List of solitary animals

References

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Agriculture document "Taxidea taxus".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Agriculture document "Taxidea taxus".- ^ Reid, F. & Helgen, K. (2008). Taxidea taxus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 21 March 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern

- ^ Wozencraft, W. Christopher (16 November 2005). "Order Carnivora (pp. 532-628)". In Wilson, Don E., and Reeder, DeeAnn M., eds. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2 vols. (2142 pp.). p. 619. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14001508.

- ^ "Taxidea". http://www.funet.fi/pub/sci/bio/life/mammalia/carnivora/mustelidae/taxidea/index.html. Retrieved 2007-08-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Long, Charles A. (1972). "Taxidea taxus". Journal of Mammalogy 26: 1–4. http://www.science.smith.edu/departments/Biology/VHAYSSEN/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-026-01-0001.pdf. Retrieved 2007-08-07.Long, Charles A. (1972). "Taxonomic Revision of the North American Badger, Taxidea taxus". Journal of Mammalogy (Journal of Mammalogy) 53 (4): 725–759. doi:10.2307/1379211. JSTOR 1379211.

- ^ Feldhamer, George A.; Bruce Carlyle Thompson, Joseph A. Chapman (2003). Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation. JHU Press. p. 683. ISBN 0-8018-7416-5. http://books.google.com/?id=-xQalfqP7BcC&pg=PA683.

- ^ American Society of Mammalogists Staff; Smithsonian Institution Staff (1999). The Smithsonian Book of North American Mammals. UBC Press. p. 179. ISBN 0-7748-0762-8. http://books.google.com/?id=qNFgzIPGuSUC&pg=PA179.

- ^ Michener, Gail R. (2004). "Hunting techniques and tool use by North American badgers preying on Richardson's ground squirrels". Journal of mammalogy 85 (5): 1019–1027. doi:10.1644/BNS-102. JSTOR 1383835.

- ^ "Badger-Coyote Associations". ecology.info. http://www.ecology.info/article.aspx?cid=10&id=24.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lindzey, Frederick G. 1982. Badger: Taxidea taxus. In: Chapman, Joseph A.; Feldhamer, George A., eds. Wild mammals of North America: Biology, management, and economics. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press: 653–663

- ^ a b c d e Long, Charles A.; Killingley, Carl Arthur. 1983. The badgers of the world. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publishing

- ^ a b Messick, John P.; Hornocker, Maurice G. (1981). "Ecology of the Badger in Southwestern Idaho". Wildlife Monographs 76 (76): 1–53. JSTOR 3830719.

- ^ Lindsey, Frederick G.. 1971. Ecology of badgers in Curlew Valley, Utah and Idaho with emphasis on movement and activity patterns. Logan, UT: Utah State Univeristy

- ^ "Mammal Species of Special Concern". dfg.ca.gov. http://www.dfg.ca.gov/wildlife/nongame/ssc/mammals.html. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ a b Banfield, A. W. F. 1974. The mammals of Canada. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press

- ^ de Vos, A. 1969. Ecological conditions affecting the production of wild herbivorous mammals on grasslands. In: Advances in ecological research. [Place of publication unknown]: [Publisher unknown]: 137–179. On file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT

- ^ Davis, Russell; Sidner, Ronnie. 1992. Mammals of woodland and forest habitats in the Rincon Mountains of Saguaro National Monument, Arizona. Technical Report NPS/WRUA/NRTR-92/06. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona, School of Renewable Natural Resources, Cooperative National Park esources Study Unit

- ^ Quinn, Ronald D. 1990. Habitat preferences and distribution of mammals in California chaparral. Res. Pap. PSW-202. Berkeley, CA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Southwest Research Station

- ^ a b Bird, Ralph D. (1930). "Biotic communities of the aspen parkland of central Canada". Ecology 11 (2): 356–442. doi:10.2307/1930270. JSTOR 1930270.

- ^ Sargeant, Alan B.; Warner, Dwain W. (1972). "Movements and denning habits of a badger". Journal of Mammalogy 53 (1): 207–210. doi:10.2307/1378851.

- ^ a b Lindzey, Frederick G. (1978). "Movement patterns of badgers in northwestern Utah". Journal of Wildlife Management 42 (2): 418–422. doi:10.2307/3800282. JSTOR 3800282.

- ^ "Ontario Badger". ontariobadgers.com. http://www.ontariobadgers.com/index.html.

- ^ Morris, Meredith J.; Reid, Vincent H.; Pillmore, Richard E.; Hammer, Mary C. 1977. Birds and mammals of Manitou Experimental Forest, Colorado. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-38. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment.

- ^ Gibson, David J. (1989). "Effects of animal disturbance on tallgrass prairie vegetation". American Midland Naturalist 121 (1): 144–154. doi:10.2307/2425665. JSTOR 2425665.

- ^ Tyser, Robin W. 1990. Ecology of fescue grasslands in Glacier National Park. In: Boyce, Mark S.; Plumb, Glenn E., eds. National Park Service Research Center, 14th annual report. Laramie, WY: University of Wyoming, National Park Service Research Center: 59–60

- ^ Skinner, Scott. 1990. Earthmover. Wyoming Wildlife. 54(2): 4–9

Further reading

- Shefferly, N. 1999. "Taxidea taxus" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 15, 2007 at University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

- Whitaker, John O. (1980-10-12). The Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mammals. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 745. ISBN 0-394-50762-2.

External links

- Ontario Badgers (information about the American Badger and the research of their endangered Ontario population)

- Miller, Ira. "Montana Animal Field Guide". http://fwp.mt.gov/fieldguide/detail_AMAJF04010.aspx. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- Streube, Donald. "American Badger, Idaho Museum of Natural History". http://imnh.isu.edu/digitalatlas/bio/mammal/Carn/muste/amba/ambafrm.htm. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- "American Badger, The University of Texas at El Paso". The University of Texas at El Paso. http://museum.utep.edu/educate/learninglinks/badger_LL.htm. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- Steve Jackson's badger page

- Smithsonian Institution - North American Mammals: Taxidea taxus

Categories:- IUCN Red List least concern species

- Badgers

- Mammals of Canada

- Mammals of the United States

- Symbols of Wisconsin

- Tool-using species

- Mammals of North America

- Monotypic mammal genera

- Animals described in 1778

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.