- Membranous glomerulonephritis

-

Membranous glomerulonephritis Classification and external resources

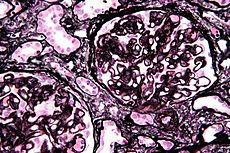

Micrograph of membranous nephropathy showing prominent glomerular basement membrane spikes. MPAS stain.ICD-10 N03.2 ICD-9 583.1 DiseasesDB 7970 eMedicine med/885 MeSH D015433 Membranous glomerulonephritis (MGN) is a slowly progressive disease of the kidney affecting mostly patients between ages of 30 and 50 years, usually Caucasian.

It is one of the more common forms of nephrotic syndrome.

Contents

Terminology

-The closely related terms membranous nephropathy[1] and membranous glomerulopathy[2] both refer to a similar constellation but without the assumption of inflammation.

-Membranous nephritis (in which inflammation is implied, but the glomerulus not explicitly mentioned) is less common, but the phrase is occasionally encountered.[3] These conditions are usually considered together.

By contrast, membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis has a similar name, but is considered a separate condition with a distinctly different causality. Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis involves the basement membrane and mesangium, while membranous glomerulonephritis involves the basement membrane but not the mesangium. (Membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis has the alternate name "mesangiocapillary glomerulonephritis", to emphasize its mesangial character.)

Causes and classification

Primary/idiopathic

85% of MGN cases are classified as primary membranous glomerulonephritis -- that is to say, the cause of the disease is idiopathic (of unknown origin or cause). This can also be referred to as idiopathic membranous nephropathy. One study has identified antibodies to an M-type phospholipase A2 receptor in 70% (26 of 37) cases evaluated.[4]

Secondary

The remainder is secondary due to:

- autoimmune conditions (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus[5])

- infections (e.g., syphilis, malaria, hepatitis B)

- drugs (e.g., captopril, NSAIDs, gold, mercury, penicillamine, probenecid).

- inorganic salts

- tumors, frequently solid tumors of the lung and colon; hematological malignancies such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia are less common.[6]

Pathogenesis

MGN is caused by circulating immune complex. The immune complexes are formed by binding of antibodies to antigens in the glomerular basement membrane. The antigens may be part of the basement membrane, or deposited from elsewhere by the systemic circulation.

The immune complex serves as an activator that triggers a response from the C5b - C9 complements, which form a membrane attack complex (MAC) on the glomerular epithelial cells. This, in turn, stimulates release of proteases and oxidants by the mesangial and epithelial cells, damaging the capillary walls and causing them to become "leaky". In addition, the epithelial cells also seem to secrete an unknown mediator that reduces nephrin synthesis and distribution.

Morphology

The defining point of MGN is the presence of subepithelial immunoglobulin-containing deposits along the glomerular basement membrane (GBM).

- By light microscopy, the basement membrane is observed to be diffusely thickened. Using Jones' stain, the GBM appears to have a "spiked" or "holey" appearance.

- On electron microscopy, subepithelial deposits that nestle against the glomerular basement membrane seems to be the cause of the thickening. Also, the podocytes lose their foot processes. As the disease progresses, the deposits will eventually be cleared, leaving cavities in the basement membrane. These cavities will later be filled with basement membrane-like material, and if the disease continues even further, the glomeruli will become sclerosed and finally hyalinized.

- Immunoflourescence microscopy will reveal typical granular deposition of immunoglobulins and complement along the basement membrane.[7]

Although it usually affects the entire glomerulus, it can affect parts of the glomerulus in some cases.[8]

Clinical presentation

Some patients may present as nephrotic syndrome with proteinuria, edema with or without renal failure. Others may be asymptomatic and may be picked up on screening or urinalysis as having proteinuria. A definitive diagnosis of membranous nephropathy requires a kidney biopsy.

Treatment

Treatment of secondary membranous nephropathy is guided by the treatment of the original disease. For treatment of idiopathic membranous nephropathy, the treatment options include immunosuppressive drugs and non-specific anti-proteinuric measures.

Immunosuppressive therapy

- Corticosteroids: They have been tried with mixed results, with one study showing prevention of progression to renal failure without improvement in proteinuria.

- Chlorambucil

- Cyclosporine[9]

- Tacrolimus

- Cyclophosphamide

- Mycophenolate mofetil

Perhaps the most difficult aspect of membranous glomerulonpehritis is deciding which patients to treat with immunosuppressive therapy as opposed to simple "background" or anti-proteinuric therapies. A large part of this difficulty is due to a lack of ability to predict which patient will progress to end-stage renal disease, or renal disease severe enough to require dialysis. Because the above medications carry risk, treatment should not be initiated without careful consideration as to risk/benefit profile. Of note, corticosteroids (typically Prednisone) alone are of little benefit. They should be combined with one of the other 5 medications, each of which, along with prednisone, has shown some benefit in slowing down progression of membranous nephropathy. It must be kept in mind, however, that each of the 5 medications also carry their own risks, on top of prednisone.

The twin aims of treating membranous nephropathy are first to induce a remission of the nephrotic syndrome and second to prevent the development of endstage renal failure. A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled studies comparing treatments of membranous nephropathy showed that regimes comprising chlorambucil or cyclophosphamide, either alone or with steroids, were more effective than symptomatic treatment or treatment with steroids alone in inducing remission of the nephrotic syndrome. A small, randomized controlled study of 17 patients with a persistent nephrotic syndrome and declining renal function suggested that ciclosporin A slowed the rate of decline of renal function: this requires confirmation in a larger trial.

Natural history

About a third of patients have spontaneous remission, another third progress to require dialysis and the last third continue to have proteinuria, without progression of renal failure.

References

- ^ Passerini P, Ponticelli C (July 2003). "Corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide, and chlorambucil therapy of membranous nephropathy". Semin. Nephrol. 23 (4): 355–61. doi:10.1016/S0270-9295(03)00052-4. PMID 12923723. http://journals.elsevierhealth.com/retrieve/pii/S0270929503000524.

- ^ Markowitz GS (May 2001). "Membranous glomerulopathy: emphasis on secondary forms and disease variants". Adv Anat Pathol 8 (3): 119–25. doi:10.1097/00125480-200105000-00001. PMID 11345236. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?issn=1072-4109&volume=8&issue=3&spage=119.

- ^ Hallegua D, Wallace DJ, Metzger AL, Rinaldi RZ, Klinenberg JR (2000). "Cyclosporine for lupus membranous nephritis: experience with ten patients and review of the literature". Lupus 9 (4): 241–51. doi:10.1191/096120300680198935. PMID 10866094. http://openurl.ingenta.com/content/nlm?genre=article&issn=0961-2033&volume=9&issue=4&spage=241&aulast=Hallegua.

- ^ Beck, LH; Bonegio, RGB; Lambeau, G; Beck, DM; Powell, DW; Cummins, TD;, Klein, JB; Salant, DJ. (July 2, 2009). "M-Type Phospholipase A2 Receptor as Target Antigen in Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy". The New England Journal of Medicine 361 (1): 11–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0810457. PMC 2762083. PMID 19571279. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/short/361/1/11.

- ^ "Renal Pathology". http://library.med.utah.edu/WebPath/RENAHTML/RENAL088.html. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ^ Ziakas PD, Giannouli S, Psimenou E, Nakopoulou L, Voulgarelis M (July 2004). "Membranous glomerulonephritis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia". Am. J. Hematol. 76 (3): 271–4. doi:10.1002/ajh.20109. PMID 15224365.

- ^ "Renal Pathology". http://library.med.utah.edu/WebPath/RENAHTML/RENAL090.html. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

- ^ Obana M, Nakanishi K, Sako M, et al. (July 2006). "Segmental membranous glomerulonephritis in children: comparison with global membranous glomerulonephritis". Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1 (4): 723–9. doi:10.2215/CJN.01211005. PMID 17699279. http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17699279.

- ^ Goumenos DS, Katopodis KP, Passadakis P, et al. (2007). "Corticosteroids and ciclosporin A in idiopathic membranous nephropathy: higher remission rates of nephrotic syndrome and less adverse reactions than after traditional treatment with cytotoxic drugs". Am. J. Nephrol. 27 (3): 226–31. doi:10.1159/000101367. PMID 17389782. http://content.karger.com/produktedb/produkte.asp?typ=fulltext&file=000101367.

Lupus nephritis Class I (Minimal mesangial glomerulonephritis) · Class II (Mesangial proliferative lupus nephritis) · Class III (Focal proliferative nephritis) · Class IV (Diffuse proliferative nephritis) · Class V (Membranous nephritis) · Class VI (Glomerulosclerosis)Urinary system · Pathology · Urologic disease / Uropathy (N00–N39, 580–599) Abdominal Primarily

nephrotic.3 Mesangial proliferative · .4 Endocapillary proliferative .5/.6 Membranoproliferative/mesangiocapillaryBy conditionType III RPG/Pauci-immuneTubulopathy/

tubulitisAny/allAny/allGeneral syndromesOtherUreterPelvic UrethraUrethritis (Non-gonococcal urethritis) · Urethral syndrome · Urethral stricture/Meatal stenosis · Urethral caruncleAny/all Obstructive uropathy · Urinary tract infection · Retroperitoneal fibrosis · Urolithiasis (Bladder stone, Kidney stone, Renal colic) · Malacoplakia · Urinary incontinence (Stress, Urge, Overflow)Categories:- Inflammations

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.