- Faroese language

-

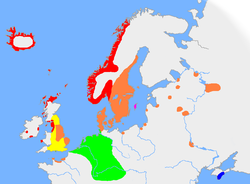

Faroese føroyskt Pronunciation [ˈføːɹɪst], [ˈføːɹɪʂt] Spoken in  Faroe Islands

Faroe Islands

Denmark

Denmark

Norway

NorwayNative speakers 48,300 (2007) Language family Indo-European- Germanic

- North Germanic

- West Scandinavian

- Faroese

- West Scandinavian

- North Germanic

Writing system Latin (Faroese alphabet) Official status Official language in  Faroe Islands

Faroe IslandsRecognised minority language in  Denmark

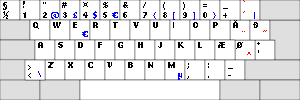

DenmarkRegulated by Faroese Language Board Føroyska málnevndin Language codes ISO 639-1 fo ISO 639-2 fao ISO 639-3 fao Linguasphere 52-AAA-ab  Faroese keyboard layout

Faroese keyboard layoutThis page contains IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks, boxes, or other symbols instead of Unicode characters. Faroese[1] (føroyskt, pronounced [ˈføːɹɪst] or [ˈføːɹɪʂt]), is an Insular Nordic language spoken by 48,000 people in the Faroe Islands and about 25,000[citation needed] Faroese people in Denmark and elsewhere. It is one of four languages descended from the Old West Norse language spoken in the Middle Ages, the others being Icelandic, Norwegian and the extinct Norn, which is thought to have been mutually intelligible with Faroese.[citation needed] Faroese and Icelandic, its closest extant relative, are not mutually intelligible in speech, but the written languages resemble each other quite closely.[2]

Contents

History

Around AD 900 the language spoken in the Faroes was Old Norse, which Norwegian settlers had brought with them during the time of the landnám that began in AD 825. However, many of the settlers were not from present-day Norway but descendants of Norwegian settlers in the Irish Sea. In addition, native Norwegian settlers often married women from Norse Ireland, Orkney, or Shetland before settling in the Faroe Islands and Iceland. As a result, Celtic languages influenced both Faroese and Icelandic. There is some debatable evidence of Celtic language place names in the Faroes: for example Mykines and Stóra & Lítla Dímun have been hypothesized to contain Celtic roots. Other examples of early-introduced words of Celtic origin are; "blak/blaðak" (buttermilk) Irish bláthach; "drunnur" (tail-piece of an animal) Irish dronn; "grúkur" (head, headhair) Irish gruaig; "lámur" (hand, paw) Irish lámh; "tarvur" (bull) Irish tarbh; and "ærgi" (pasture in the outfield) Irish áirge.[3]

Between the 9th and the 15th centuries a distinct Faroese language evolved, although it was still mutually intelligible with the Old West Norse language and was closely related to the Norn language of Orkney and Shetland.

Until the 15th century Faroese had an orthography similar to Icelandic and Norwegian, but after the Reformation in 1536 the ruling Danes outlawed its use in schools, churches and official documents. The islanders continued to use the language in ballads, folktales and everyday life. This maintained a rich spoken tradition, but for 300 years the language was unwritten.

This changed when Venceslaus Ulricus Hammershaimb and the Icelandic grammarian and politician, Jón Sigurðsson, published a written standard for Modern Faroese in 1854 which is still in existence. Although this would have been an opportunity to create a phonetically true orthography like that of Finnish, they produced an archaic, Old Norse-based orthography similar to that of Icelandic. The letter ð, for example, has no specific phoneme attached to it. Furthermore, although the letter 'm' corresponds to the bilabial nasal as it does in English, it also corresponds to the alveolar nasal in the dative ending -um [ʊn].

Hammershaimb and Sigurðsson's orthography met with opposition for its complexity, and a rival system was devised by Jakob Jakobsen. Jakobsen's orthography was closer to the spoken language, but was never taken up by speakers.[citation needed]

In 1937 Faroese replaced Danish as the official school language, in 1938 as the church language, and in 1948 as the national language by the Home Rule Act of the Faroes. However, Faroese did not become the common language of media and advertising until the 1980s.[citation needed] Today Danish is considered a foreign language, though around five percent of Faroe Islanders learn it as a first language and it is a required subject for students in third grade[4] and up.

Learning Faroese

It is unusual for Faroese to be taught at universities outside the Faroes, although it is occasionally included in Scandinavian studies; University College London and the University of Copenhagen have course options in Faroese for students reading Scandinavian Studies.[5] Most students, therefore, learn it autodidactically from books, by listening to Faroese on radio [6] and through correspondence with Faroese people. A good opportunity for learning Faroese is also by visiting websites.

The University of the Faroe Islands offers an annual three-week Summer Institute which includes:

- Fifty lessons of Faroese grammar and language exercises.

- Twenty lectures on linguistics, culture (oral poetry and modern literature), society and nature.

- Two excursions to places of historical and geographical interest.

Alphabet

The Faroese alphabet consists of 29 letters derived from the Latin alphabet:

Majuscule Forms (also called uppercase or capital letters) A Á B D Ð E F G H I Í J K L M N O Ó P R S T U Ú V Y Ý Æ Ø Minuscule Forms (also called lowercase or small letters) a á b d ð e f g h i í j k l m n o ó p r s t u ú v y ý æ ø Notes:

- Ð, ð can never come at the beginning of a word, but can occur in capital letters in logos or on maps, such as SUÐUROY (Southern Isle).

- Ø, ø can also be written Ö, ö in poetic language, such as Föroyar (the Faroes) (cf. Swedish-Icelandic typographic/orthographic tradition vs. Norwegian-Danish). In handwriting Ő, ő is sometimes used. Earlier versions of the orthography used both ø and ö with ø being the long ø and ö being the short equivalent.

- While C, Q, W, X, and Z are not found in the Faroese language, X was known in earlier versions of Hammershaimb's orthography, such as Saxun for Saksun.

- While the Faroese keyboard layout allows one to write in Latin, English, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian, Finnish, etc., the Old Norse and Modern Icelandic letter þ is missing. In related Faroese words it is written as <t> or as <h>, and if an Icelandic name has to be transcribed, <th> is common.

Phonology

Vowels

Grapheme Name Short[falling or rising?] Long A, a fyrra a [ˈfɪɹːa ɛaː] ("leading a") /a/ /ɛaː/ Á, á á [ɔaː] /ɔ/ /ɔaː/ E, e e [eː] /ɛ/ /eː/ I, i fyrra i [ˈfɪɹːa iː] ("leading i") /ɪ/ /iː/ Í, í fyrra í [ˈfɪɹːa ʊiː] ("leading í") /ʊi/ /ʊiː/ O, o o [oː] /ɔ/ /oː/ Ó, ó ó [ɔuː] /œ/ /ɔuː/ U, u u [uː] /ʊ/ /uː/ Ú, ú ú [ʉuː] /ʏ/ /ʉuː/ Y, y seinna i [ˈsaiːdna iː] ("latter i") /ɪ/ /iː/ Ý, ý seinna í [ˈsaiːdna ʊiː] ("latter í") /ʊi/ /ʊiː/ Æ, æ seinna a [ˈsaiːdna ɛaː] ("latter a") /a/ /ɛaː/ Ø, ø ø [øː] /œ/ /øː/ EI, ei ei [eiː] /ei/ /eiː/ EY, ey ey [eyː] /ey/ /eyː/ OY, oy oy [oyː] /oy/ /oyː/ Other vowels ei – /ai/ /aiː/ ey – /ɛ/ /ɛiː/ oy – /ɔi/ /ɔiː/ As in several other Germanic languages, stressed vowels in Faroese are long when not followed by two or more consonants. Two consonants or a consonant cluster usually indicates a short vowel. Exceptions may be short vowels in particles, pronouns, adverbs, and prepositions in unstressed positions, consisting of just one syllable.

As may be seen on the table to the left, Faroese (like English) has a very atypical pronunciation of its vowels, with odd offglides and other features. For example, long í and ý sound almost like a long Hiberno-English i, and long ó like an American English long o.

Short vowels in endings

While in other Germanic languages a short /e/ is common for inflectional endings, Faroese uses /a, i, u/. This means that there are no unstressed short vowels except for these three. Even if a short unstressed /e/ is seen in writing, it will be pronounced like /i/: áðrenn [ˈɔaːɹɪnː] (before). Very typical are endings like -ur, -ir, -ar. The dative is often indicated by -um which is always pronounced [ʊn].

- [a] – bátar [ˈbɔaːtaɹ] (boats), kallar [ˈkadlaɹ] ((you) call, (he) calls)

Unstressed /i/ and /u/ in dialects Borðoy, Kunoy, Tórshavn Viðoy, Svínoy, Fugloy Suðuroy Elsewhere (standard) gulur (yellow) [ˈɡ̊uːləɹ] [ˈɡ̊uːləɹ] [ˈɡ̊uːløɹ] [ˈɡ̊uːlʊɹ] gulir (yellow pl.) [ˈɡ̊uːləɹ] [ˈɡ̊uːləɹ] [ˈɡ̊uːløɹ] [ˈɡ̊uːlɪɹ] bygdin (the town) [ˈb̥ɪɡ̊d̥ɪn] [ˈb̥ɪɡ̊d̥ən] [ˈb̥ɪɡ̊d̥øn] [ˈb̥ɪɡ̊d̥ɪn] bygdum (towns dat. pl.) [ˈb̥ɪɡ̊d̥ʊn] [ˈb̥ɪɡ̊d̥ən] [ˈb̥ɪɡ̊d̥øn] [ˈb̥ɪɡ̊dʊn] Source: Faroese: An Overview and Reference Grammar, 2004 (page 350) - [ɪ] – gestir [ˈdʒɛstɪɹ] (guests), dugir [ˈduːjɪɹ] ((you, he) can)

- [ʊ] – bátur [ˈbɔaːtʊɹ] (boat), gentur [dʒɛntʊɹ] (girls), rennur [ˈɹenːʊɹ] ((you) run, (he) runs).

In some dialects, unstressed /ʊ/ is realized as [ø] or is reduced further to [ə]. /ɪ/ goes under a similar reduction pattern so unstressed /ʊ/ and /ɪ/ can rhyme. This can cause spelling mistakes related to these two vowels. The table to the right displays the different realizations in different dialects.

Glide insertion

Faroese avoids having a hiatus between two vowels by inserting a glide. Orthographically, this is shown in three ways:

- vowel + ð + vowel

- vowel + g + vowel

- vowel + vowel

Typically, the first vowel is long and in words with two syllables always stressed, while the second vowel is short and unstressed. In Faroese, short and unstressed vowels can only be /a/, /i/, /u/.

Ð and G as glides

Glide insertion First vowel Second vowel Examples i [ɪ] u [ʊ] a [a] Grapheme Phoneme Glide I-surrounding Type 1 i, y [iː] [j] [j] [j] sigið, siður, siga í, ý [ʊiː] [j] [j] [j] mígi, mígur, míga ey [ɛiː] [j] [j] [j] reyði, reyður, reyða ei [aiː] [j] [j] [j] reiði, reiður, reiða oy [ɔiː] [j] [j] [j] noyði, royður, royða U-surrounding Type 2 u [uː] [w] [w] [w] suði, mugu, suða ó [ɔuː] [w] [w] [w] róði, róðu, Nóa ú [ʉuː] [w] [w] [w] búði, búðu, túa I-surrounding Type 2, U-surrounding Type 2, A-surrounding Type 1 a, æ [ɛaː] [j] [v] – ræði, æðu, glaða á [ɔaː] [j] [v] – ráði, fáur, ráða e [eː] [j] [v] – gleði, legu, gleða o [oː] [j] [v] – togið, smogu, roða ø [øː] [j] [v] – løgin, røðu, høgan Source: Faroese: An Overview and Reference Grammar, 2004 (page 38) <Ð> and <G> are used in Faroese orthography to indicate one of a number of glides rather than any one phoneme. This can be:

- [j]

- "I-surrounding, type 1" – after /i, y, í, ý, ei, ey, oy/: bíða [ˈbʊija] (to wait), deyður [ˈdɛijʊɹ] (dead), seyður [ˈsɛijʊɹ] (sheep)

- "I-surrounding, type 2" – between any vowel (except "u-vowels" /ó, u, ú/) and /i/: kvæði [ˈkvɛajɪ] (ballad), øði [ˈøːjɪ] (rage).

- [w] "U-surrounding, type 1" – after /ó, u, ú/: Óðin [ˈɔuwɪn] (Odin), góðan morgun! [ˌɡɔuwan ˈmɔɹɡʊn] (good morning!), suður [ˈsuːwʊɹ] (south), slóða [ˈslɔuwa] (to make a trace).

- [v]

- "U-surrounding, type 2" – between /a, á, e, æ, ø/ and /u/: áður [ˈɔavʊɹ] (before), leður [ˈleːvʊɹ] (leather), í klæðum [ɪˈklɛavʊn] (in clothes), í bløðum [ɪˈbløːvʊn] (in newspapers).

- "A-surrounding, type 2"

- These are exceptions (there is also a regular pronunciation): æða [ˈɛava] (eider-duck), røða [ˈɹøːva] (speech).

- The past participles have always [v]: elskaðar [ˈɛlskavaɹ] (beloved, nom., acc. fem. pl.)

- Silent

- "A-surrounding, type 1" – between /a, á, e, o/ and /a/ and in some words between <æ, ø> and <a>: ráða [ˈɹɔːa] (to advise), gleða [ˈɡ̊leːa] (to gladden, please), boða [ˈboːa] (to forebode), kvøða [ˈkvøːa] (to chant), røða [ˈɹøːa] (to make a speech)

Skerping (sharpening)

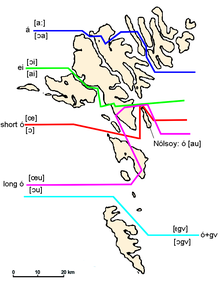

Skerping Written Pronunciation instead of -ógv- [ɛɡv] *[ɔuɡv] -úgv- [ɪɡv] *[ʉuɡv] -eyggj- [ɛdːʒ] *[ɛidːʒ] -íggj-, -ýggj- [ʊdːʒ] *[ʊidːʒ] -eiggj- [adːʒ] *[aidːʒ] -oyggj- [ɔdːʒ] *[ɔidːʒ] The so-called "skerping" (Thráinsson et al. use the term "Faroese Verschärfung" – in Faroese, skerping /ʃɛɹpɪŋɡ/ means "sharpening") is a typical phenomenon of fronting back vowels before [ɡv] and monophthongizing certain diphthongs before [dːʒ]. Skerping is not indicated orthographically. These consonants occur often after /ó, ú/ (ógv, úgv) and /ey, í, ý, ei, oy/ when no other consonant is following.

- [ɛɡv]: Jógvan [ˈjɛɡvan] (a form of the name John), Gjógv [dʒɛɡv] (cleft)

- [ɪɡv]: kúgv [kɪɡv] (cow), trúgva [ˈtɹɪɡva] (believe), but: trúleysur [ˈtɹʉuːlɛisʊɹ] (faithless)

- [ɛdːʒ]: heyggjur [ˈhɛdːʒʊɹ] (high, burial mound), but heygnum [ˈhɛiːnʊn] (dat. sg. with suffix article)

- [ʊdːʒ]: nýggjur [ˈnʊdːʒʊɹ] (new m.), but nýtt [nʊiʰtː] (n.)

- [adːʒ]: beiggi [ˈbadːʒɪ] (brother)

- [ɔdːʒ]: oyggj [ɔdːʒ] (island), but oynna [ˈɔitnːa] (acc. sg. with suffix article)

Consonants

Labial Apical Post-

alveolarPalatal Velar Glottal Plosive pʰ, p tʰ, t kʰ, k Affricate tʃʰ, tʃ Fricative f v s ʃ h Nasal m n ɲ ŋ Approximant w l ɹ j There are several phonological processes involved in Faroese, including:

- Liquids are devoiced before voiceless consonants

- Nasals generally assume the place of articulation and laryngeal settings of following consonants.

- Velar stops palatalize to postalveolar affricates before /j/ /e/ /ɪ/ /y/ and /ɛi/

- /v/ becomes /f/ before voiceless consonants

- /s/ becomes /ʃ/ after /ɛi, ai, ɔi/ and before /j/ and may assimilate the retroflexion of a preceding /r/ to become [ʂ].

- Pre-occlusion of original <ll> to [dl] and <nn> to [dn].

Omissions in consonant clusters

Faroese tends to omit the first or second consonant in clusters of different consonants:

- fjals [fjals] (mountain's gen.) instead of *[fjadls] from [fjadl] (nom.). Other examples for genitives are: barns [ˈbans] (child's), vatns [van̥s] (lake's, water's).

- hjálpti [jɔl̥tɪ] (helped) past sg. instead of *[ˈjɔlpta] from hjálpa [ˈjɔlpa]. Other examples for past forms are: sigldi [ˈsɪldɪ] (sailed), yrkti [ˈɪɹ̥tɪ] (wrote poetry).

- homophone are fylgdi (followed) and fygldi (caught birds with net): [ˈfɪldɪ].

- skt will be:

- [st] in words of more than one syllable: føroyskt [ˈføːɹɪst] (Faroese n. sg.; also [ˈføːɹɪʂt]) russiskt [ˈɹʊsːɪst] (Russian n. sg.), íslendskt [ˈʊʃlɛŋ̊st] (Icelandic n. sg.).

- [kst] in monosyllables: enskt [ɛŋ̊kst] (English n. sg.), danskt [daŋ̊kst] (Danish n. sg.), franskt [fɹaŋ̊kst] (French n. sg.), spanskt [spaŋ̊kst] (Spanish n. sg.), svenskt [svɛŋ̊kst] (Swedish n. sg.), týskt [tʊkst] (German n. sg.).

- However [ʂt] in: írskt [ʊʂt] (Irish n. sg.), norskt [nɔʂt] (Norwegian n. sg.)

Faroese Words and Phrases in comparison to English, and Other Germanic languages

Faroese English Icelandic Danish Dutch Vælkomin Welcome Velkomin Velkommen Welkom Farvæl Farewell Farðu heill Farvel Vaarwel Hvat eitur/heitir tú? What's your name? Hvað heitir þú? Hvad hedder du? Hoe heet je? Hvussu gongur? How are you? Hvernig gengur? Hvordan går det? Hoe gaat het met je? Hvussu gamal ert tú? How old are you? Hversu gamall ertu? Hvor gammel er du? Hoe oud ben je? Reytt/Reyður Red Rauður Rødt/Rød Rood Blátt/bláur Blue Blár Blåt/Blå Blauw Hvítt/hvítur White Hvítur Hvidt/Hvid Wit Grammar

Faroese grammar is related and very similar to that of modern Icelandic and Old Norse. Faroese is an inflected language with three grammatical genders and four cases: nominative, accusative, dative and genitive.

Faroese numbers and expressions

Number Faroese 0 null 1 eitt 2 tvey 3 trý 4 fýra 5 fimm 6 seks 7 sjey 8 átta 9 níggju 10 tíggju 11 ellivu 12 tólv 13 trettan 14 fjúrtan 15 fimtan 16 sekstan 17 seytjan 18 átjan 19 nítjan 20 tjúgu 21 einogtjúgu 22 tveyogtjúgu 30 tredivu, tríati 40 fjøruti, fýrati 50 hálvtrýss, fimmti 60 trýss, seksti 70 hálvfjers, sjeyti 80 fýrs, áttati 90 hálvfems, níti 100 hundrað 1000 (eitt) túsund See also

Further reading

This is a chronological list of books about Faroese still available.

- V.U. Hammershaimb: Færøsk Anthologi. Copenhagen 1891 (no ISBN, 2 volumes, 4th printing, Tórshavn 1991) (in Danish)

- M.A. Jacobsen, Chr. Matras: Føroysk–donsk orðabók. Tórshavn, 1961. (no ISBN, 521 pages, Faroese–Danish dictionary)

- W.B. Lockwood: An Introduction to Modern Faroese. Tórshavn, 1977. (no ISBN, 244 pages, 4th printing 2002)

- Eigil Lehmann: Føroysk–norsk orðabók. Tórshavn, 1987 (no ISBN, 388 p.) (Faroese–Norwegian dictionary)

- Hjalmar Petersen, Marius Staksberg: Donsk–Føroysk orðabók. Tórshavn, 1995. (879 p.) ISBN 99918-41-51-2 (Danish–Faroese dictionary)

- Tórður Jóansson: English loanwords in Faroese. Tórshavn, 1997. (243 pages) ISBN 99918-49-14-9

- Johan Hendrik W. Poulsen: Føroysk orðabók. Tórshavn, 1998. (1483 pages) ISBN 99918-41-52-0 (in Faroese)

- Annfinnur í Skála: Donsk-føroysk orðabók. Tórshavn 1998. (1369 pages) ISBN 99918-42-22-5 (Danish–Faroese dictionary)

- Michael Barnes: Faroese Language Studies Studia Nordica 5, Supplementum 30. Tórshavn, 2002. (239 pages) ISBN 99918-41-30-X

- Höskuldur Thráinsson (Þráinsson), Hjalmar P. Petersen, Jógvan í Lon Jacobsen, Zakaris Svabo Hansen: Faroese. An Overview and Reference Grammar. Tórshavn, 2004. (500 pages) ISBN 99918-41-85-7

- Richard Kölbl: Färöisch Wort für Wort. Bielefeld 2004 (in German)

- Gianfranco Contri: Dizionario faroese-italiano = Føroysk-italsk orðabók. Tórshavn, 2004. (627 p.) ISBN 99918-41-58-X (Faroese–Italian dictionary)

- Jón Hilmar Magnússon: Íslensk-færeysk orðabók. Reykjavík, 2005. (877 p.) ISBN 99796-61-79-8 (Icelandic–Faroese dictionary)

- Annfinnur í Skála / Jonhard Mikkelsen: Føroyskt / enskt – enskt / føroyskt, Vestmanna: Sprotin 2008. (Faroese–English / English–Faroese dictionary, 2 volumes)

- Adams, Jonathan & Hjalmar P. Petersen. Faroese: A Language Course for beginners Grammar & Textbook. Tórshavn, 2009: Stiðin (704 p.) ISBN 978-99918-42-54-7

- Petersen, Hjalmar P. 2009. Gender Assignment in Modern Faroese. Hamborg. Kovac

- Petersen, Hjalmar P. 2010. The Dynamics of Faroese-Danish Language Contact. Heidelberg. Winter

- Faroese/German anthology “From Djurhuus to Poulsen – Faroese Poetry during 100 Years”, academic advice: Turið Sigurðardóttir, lineartranslation: Inga Meincke (2007), ed. by Paul Alfred Kleinert

References

- ^ While the spelling Faeroese is also seen, Faroese is the spelling used in grammars, textbooks, scientific articles and dictionaries between Faroese and English.

- ^ Language and nationalism in Europe, p. 106, Stephen Barbour, Cathie Carmichael, Oxford University Press, 2000

- ^ Chr. Matras. Greinaval – málfrøðigreinir. FØROYA FRÓÐSKAPARFELAG 2000

- ^ Logir.fo – Homepage Database of laws on the Faroe Islands (Faroese)

- ^ http://www.ucl.ac.uk/scandinavian-studies/faroese

- ^ Faroese internet radio streams

External links

- Føroysk orðabók (the Faroese–Faroese dictionary of 1998 online)

- Sprotin (complete English-Faroese/Faroese-English and Danish–Faroese online dictionary – requires a subscription)

- Faroese online syntactic analyser and morphological analyser/generator

- FMN.fo – Faroese Language Committee (Official site with further links)

- 'Hover & Hear' Faroese pronunciations, and compare with equivalents in English and other Germanic languages.

- Ethnologue report on Faroese

- Useful Faroese Words & Phrases for Travelers

- How to count in Faroese

Modern Germanic languages and dialects North Germanic West ScandinavianEast ScandinavianWest Germanic Achterhooks • Drèents • East Frisian Low Saxon • Gronings • Low German • Plautdietsch • Sallaans • Stellingwarfs • Tweants • Veluws • WestphalianAlemán Coloniero • Alsatian • Austro-Bavarian • Main-Franconian • Cimbrian • Hutterite German • Mócheno • Swabian • Swiss German • Walser - Germanic

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.