- Plerixafor

-

Plerixafor

Systematic (IUPAC) name 1,1′-[1,4-Phenylenebis(methylene)]bis [1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane] Clinical data AHFS/Drugs.com Consumer Drug Information MedlinePlus a609018 Pregnancy cat. D(US) Legal status ℞-only (US) Routes Subcutaneous injection Pharmacokinetic data Protein binding Up to 58% Metabolism None Half-life 3–5 hours Excretion Renal Identifiers CAS number 155148-31-5

ATC code L03AX16 PubChem CID 65015 IUPHAR ligand 844 DrugBank DB06809 ChemSpider 58531

UNII S915P5499N

KEGG D08971

ChEMBL CHEMBL18442

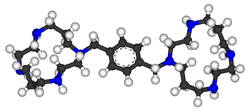

Synonyms JM 3100, AMD3100 Chemical data Formula C28H54N8 Mol. mass 502.782 g/mol SMILES eMolecules & PubChem  (what is this?) (verify)

(what is this?) (verify)Plerixafor (rINN and USAN, trade name Mozobil) is an immunostimulant used in to multiply hematopoietic stem cells in cancer patients. The stem cells are subsequently transplanted back to the patient. The drug was developed by AnorMED which was subsequently bought by Genzyme.

Contents

History

Plerixafor was initially developed at the Johnson Matthey Technology Centre for potential use in the treatment of HIV[1] because of its role in the blocking of CXCR4, a chemokine receptor which acts as a co-receptor for certain strains of HIV (along with the virus's main cellular receptor, CD4). Development of this indication was terminated because of lacking oral availability and cardiac disturbances. Further studies led to the new indication for cancer patients.[2]

Indications

Peripheral blood stem cell mobilization, which is important as a source of hematopoietic stem cells for transplantation, is generally performed using granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), but is ineffective in around 15 to 20% of patients. Combination of G-CSF with plerixafor increases the percentage of persons that respond to the therapy and produce enough stem cells for transplantation.[3] The drug is approved for patients with lymphoma and multiple myeloma.[4]

Contraindications

Pregnancy and lactation

Studies in pregnant animals have shown teratogenic effects. Plerixafor is therefore contraindicated in pregnant women except in critical cases. Fertile women are required to use contraception. It is not known whether the drug is secreted into the breast milk. Breast feeding should be discontinued during therapy.[4]

Adverse effects

Nausea, diarrhea and local reactions were observed in over 10% of patients. Other problems with digestion and general symptoms like dizziness, headache, and muscular pain are also relatively common; they were found in more than 1% of patients. Allergies occur in less than 1% of cases. Most adverse effects in clinical trials were mild and transient.[4][5]

The European Medicines Agency has listed a number of safety concerns to be evaluated on a post-marketing basis, most notably the theoretical possibilities of spleen rupture and tumor cell mobilisation. The first concern has been raised because splenomegaly was observed in animal studies, and G-CSF can cause spleen rupture in rare cases. Mobilisation of tumor cells could occur, not as a direct consequence of plerixafor application, but following the re-infusion of stem cells. Neither of these adverse effects has been observed in humans.[6]

Chemical properties

Plerixafor is a macrocyclic compound and a bicyclam derivative.[3] It is a strong base; all eight nitrogen atoms accept protons readily. The two macrocyclic rings form chelate complexes with bivalent metal ions, especially zinc, copper and nickel, as well as cobalt and rhodium. The biologically active form of plerixafor is its zinc complex.[7]

Synthesis

Three of the four nitrogen atoms of the macrocycle 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecan are protected with tosyl groups. The product is treated with 1,4-dimethoxybenzene or 1,4-bis(brommethyl)benzene and potassium carbonate in acetonitrile. After cleaving of the tosyl groups with hydrobromic acid, plerixafor octahydrobromide is obtained.[8]

Pharmacokinetics

Following subcutaneous injection, plerixafor is absorbed quickly and peak concentrations are reached after 30 to 60 minutes. Up to 58% are bound to plasma proteins, the rest mostly resides in extravascular compartments. The drug is not metabolized in significant amounts; no interaction with the cytochrome P450 enzymes or P-glycoproteins has been found. Plasma half life is 3 to 5 hours. Plerixafor is excreted via the kidneys, with 70% of the drug being excreted within 24 hours.[4]

Pharmacodynamics

In the form of its zinc complex, plerixafor acts as an antagonist (or perhaps more accurately a partial agonist) of the alpha chemokine receptor CXCR4 and an allosteric agonist of CXCR7.[9] The CXCR4 alpha-chemokine receptor and one of its ligands, SDF-1, are important in hematopoietic stem cell homing to the bone marrow and in hematopoietic stem cell quiescence. The in vivo effect of plerixafor with regard to ubiquitin, the alternative endogenous ligand of CXCR4, is unknown. Plerixafor has been found to be a strong inducer of mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells from the bone marrow to the bloodstream as peripheral blood stem cells.[10]

Interactions

No interaction studies have been conducted. The fact that plerixafor does not interact with the cytochrome system indicates a low potential for interactions with other drugs.[4]

Legal status

Plerixafor has orphan drug status in the United States and European Union for the mobilization of hematopoietic stem cells. It was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this indication on December 15, 2008.[11] In Europe, the drug was approved after a positive Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use assessment report on 29 May 2009.[6]

Research

Small molecule cancer therapy

Plerixafor was seen to reduce metastasis in mice in several studies.[12] It has also been shown to reduce recurrence of glioblastoma in a mouse model after radiotherapy. In this model, the cancer surviving radiation are critically depended on bone marrow derived cells for vasculogenesis whose recruitment mediated by SDF-1 CXCR4 interaction is blocked by plerixafor.[13]

Use in generation of other stem cells

Researchers at Imperial College have demonstrated that plerixafor in combination with vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) can produce mesenchymal stem cells and endothelial progenitor cells in mice.[14]

Other uses

Blockade of CXCR4 signalling by plerixafor (AMD3100) has also unexpectedly been found to be effective at counteracting opioid-induced hyperalgesia produced by chronic treatment with morphine, though only animal studies have been conducted as yet.[15]

References

- ^ De Clercq, E; Yamamoto, N; Pauwels, R; Balzarini, J; Witvrouw, M; De Vreese, K; Debyser, Z; Rosenwirth, B et al. (1994). "Highly potent and selective inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus by the bicyclam derivative JM3100". Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 38 (4): 668–74. PMC 284523. PMID 7913308. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=284523.

- ^ Davies, S. L.; Serradell, N.; Bolós, J.; Bayés, M. (2007). "Plerixafor Hydrochloride". Drugs of the Future 32 (2): 123. doi:10.1358/dof.2007.032.02.1071897.

- ^ a b &Na; (2007). "Plerixafor". Drugs in R & D 8 (2): 113–119. doi:10.2165/00126839-200708020-00006. PMID 17324009.

- ^ a b c d e Haberfeld, H, ed (2009) (in German). Austria-Codex (2009/2010 ed.). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. ISBN 3-85200-196-X.

- ^ Wagstaff, A. J. (2009). "Plerixafor". Drugs 69 (3): 319. doi:10.2165/00003495-200969030-00007. PMID 19275275.

- ^ a b "CHMP Assessment Report for Mozobil". European Medicines Agency. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/001030/WC500030689.pdf.

- ^ Esté, JA; Cabrera, C; De Clercq, E; Struyf, S; Van Damme, J; Bridger, G; Skerlj, RT; Abrams, MJ et al. (1999). "Activity of different bicyclam derivatives against human immunodeficiency virus depends on their interaction with the CXCR4 chemokine receptor". Molecular pharmacology 55 (1): 67–73. PMID 9882699.

- ^ Bridger, G.; et al. (1993). "Linked cyclic polyamines with activity against HIV. WO/1993/012096". http://www.wipo.int/pctdb/en/wo.jsp?wo=1993012096.

- ^ Kalatskaya, I.; Berchiche, Y. A.; Gravel, S.; Limberg, B. J.; Rosenbaum, J. S.; Heveker, N. (2009). "AMD3100 is a CXCR7 Ligand with Allosteric Agonist Properties". Molecular Pharmacology 75: 1240. doi:10.1124/mol.108.053389. PMID 19255243.

- ^ Cashen, A. F.; Nervi, B.; Dipersio, J. (2007). "AMD3100: CXCR4 antagonist and rapid stem cell-mobilizing agent". Future Oncology 3 (1): 19–27. doi:10.2217/14796694.3.1.19. PMID 17280498.

- ^ "Mozobil approved for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and multiple myeloma" (Press release). Monthly Prescribing Reference. December 18, 2008. http://www.prescribingreference.com/news/showNews/which/MozobilApprovedForNonHodgkinsLymphomaAndMultipleMyeloma121801. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

- ^ Smith, M. C. P.; Luker, K. E.; Garbow, J. R.; Prior, J. L.; Jackson, E.; Piwnica-Worms, D.; Luker, G. D. (2004). "CXCR4 Regulates Growth of Both Primary and Metastatic Breast Cancer". Cancer Research 64 (23): 8604–8612. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1844. PMID 15574767.

- ^ Kioi, M.; Vogel, H.; Schultz, G.; Hoffman, R. M.; Harsh, G. R.; Brown, J. M. (2010). "Inhibition of vasculogenesis, but not angiogenesis, prevents the recurrence of glioblastoma after irradiation in mice". Journal of Clinical Investigation 120 (3): 694–705. doi:10.1172/JCI40283. PMC 2827954. PMID 20179352. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2827954.

- ^ Pitchford, S.; Furze, R.; Jones, C.; Wengner, A.; Rankin, S. (2009). "Differential Mobilization of Subsets of Progenitor Cells from the Bone Marrow". Cell Stem Cell 4 (1): 62–72. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2008.10.017. PMID 19128793.

- ^ Wilson NM, Jung H, Ripsch MS, Miller RJ, White FA (March 2011). "CXCR4 Signaling Mediates Morphine-induced Tactile Hyperalgesia". Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 25 (3): 565–73. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2010.12.014. PMC 3039030. PMID 21193025. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=3039030.

External links

Immunomodulators: Immunostimulants (L03) Endogenous G-CSF (Filgrastim/Pegfilgrastim, Lenograstim) • GM-CSF (Molgramostim, Sargramostim) • SCF (Ancestim)alpha: Interferon alpha natural • Interferon alfa-2a/Peginterferon alfa-2a • Interferon alfa-2b/Peginterferon alfa-2b • Interferon alfa-n1 • Interferon alfacon-1

beta: Interferon beta natural • Interferon beta-1a • Interferon beta-1b

Interferon gammaOther protein/peptidePegademase • Immunocyanin • Tasonermin • Prolactin • Growth hormoneOtherExogenous vaccine (BCG vaccine, Melanoma vaccine) • beta-glucan (Lentinan) • Mifamurtide • thiazolidine (Pidotimod) • heterocyclic compound (Plerixafor) • polyribonucleotide (Polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid) • hydroxyquinoline (Roquinimex) • oligopeptide (Glatiramer acetate, Thymopentin)Categories:- Orphan drugs

- Immunostimulants

- Nitrogen heterocycles

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.