- Ulugh Beg

-

Ulugh Bek

Forensic facial reconstructionBorn March 22, 1394

SultaniyehDied October 27, 1449 Occupation astronomer, mathematician and sultan Known for trigonometry and spherical geometry Relatives Timur, Shah Rukh Ulugh Bek (Persian: میرزا محمد طارق بن شاہرخ الغبیگ - Mīrzā Muhammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrukh Uluġ Bek) (22 March 1394 in Sultaniyeh (Persia) – October 27, 1449 (Samarkand)) was a Timurid ruler as well as an astronomer, mathematician and sultan. His commonly-known name is not truly a personal name, but rather a moniker, which can be loosely translated as "Great Ruler" or "Patriarch Ruler" and was the Turkic equivalent of Timur's Perso-Arabic title Amīr-e Kabīr.[1] His real name was Mīrzā Mohammad Tāraghay bin Shāhrokh. Ulugh Beg was also notable for his work in astronomy-related mathematics, such as trigonometry and spherical geometry. He built the great observatory in Samarkand between 1424 and 1429.

Contents

Early life

He was the grandson of the conqueror, Timur (Tamerlane) (1336–1405), and oldest son of Shah Rukh, both of whom came from the Turkicized[2] Barlas tribe of Transoxiana (now Uzbekistan). His mother was a Turkic noblewoman named Goharshad. Ulugh Beg was born in Sultaniyeh in Persia. As a child he wandered through a substantial part of the Middle East and India as his grandfather expanded his conquests in those areas. With Timur's death, however, and the accession of Ulugh Beg's father to much of the Timurid Empire, he settled in Samarkand, which had been Timur's capital. After Shah Rukh moved the capital to Herat (in modern Afghanistan), sixteen-year-old Ulugh Beg became the shah's governor in Samarkand in 1409. In 1411, he became the sovereign ruler of the whole Mavarannahr khanate.

Science

The teenaged ruler set out to turn the city into an intellectual center for the empire. Between 1417 and 1420, he built a madrasa ("university" or "institute") on Registan Square in Samarkand (currentUzbekistan) , and he invited numerous Islamic astronomers and mathematicians to study there. The madrasa building still survives. Ulugh Beg's most famous pupil in astronomy was Ali Qushchi (died in 1474).

Ulugh Beg Observatory in Samarkand. In Ulugh Beg's time, these walls were lined with polished marble.

Astronomy

His own particular interests concentrated on astronomy, and, in 1428, he built an enormous observatory, called the Gurkhani Zij, similar to Tycho Brahe's later Uraniborg as well as Taqi al-Din's observatory in Istanbul. Lacking telescopes to work with, he increased his accuracy by increasing the length of his sextant; the so-called Fakhri sextant had a radius of about 36 meters (118 ft) and the optical separability of 180" (seconds of arc).

Using it, he compiled the 1437 Zij-i-Sultani of 994 stars, generally considered[who?] the greatest star catalogue between those of Ptolemy and Brahe, a work that stands alongside Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi's Book of Fixed Stars. The serious errors which he found in previous Arabian star catalogues (many of which had simply updated Ptolemy's work, adding the effect of precession to the longitudes) induced him to redetermine the positions of 992 fixed stars, to which he added 27 stars from Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi's catalogue Book of Fixed Stars from the year 964, which were too far south for observation from Samarkand. This catalogue, one of the most original of the Middle Ages, was first edited by Thomas Hyde at Oxford in 1665 under the title Tabulae longitudinis et latitudinis stellarum fixarum ex observatione Ulugbeighi and reprinted in 1767 by G. Sharpe. More recent editions are those by Francis Baily in 1843 in vol. xiii of the Memoirs of the Royal Astronomical Society and by Edward Ball Knobel in Ulugh Beg's Catalogue of Stars, Revised from all Persian Manuscripts Existing in Great Britain, with a Vocabulary of Persian and Arabic Words (1917).

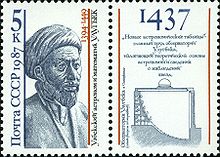

Ulugh Beg and his astronomical observatory scheme, depicted on the 1987 USSR stamp. He was one of Islam's greatest astronomers during the Middle Ages.

Ulugh Beg and his astronomical observatory scheme, depicted on the 1987 USSR stamp. He was one of Islam's greatest astronomers during the Middle Ages.

In 1437, Ulugh Beg determined the length of the sidereal year as 365.2570370...d = 365d 6h 10m 8s (an error +58s). In his measurements within many years he used a 50 m high gnomon. This value was improved by 28s in 1525 by Nicolaus Copernicus, who appealed to the estimation of Thabit ibn Qurra (826-901), which was accurate to +2s. However, Beg later measured another more precise value as 365d 5h 49m 15s, which has an error of +25s, making it more accurate than Copernicus' estimate which had an error of +30s. Beg also determined the Earth's axial tilt as 23.52 degrees, which remains the most accurate measurement to date. It was more accurate than later measurements by Copernicus and Tycho Brahe, and matches the currently accepted value precisely.[3]

Mathematics

In mathematics, Ulugh Beg wrote accurate trigonometric tables of sine and tangent values correct to at least eight decimal places.

Death

Ulugh's scientific expertise was not matched by his skills in governance. He lost some battles to rival kingdoms, and, in 1448, he massacred the people of Herat after defeating Mirza Ala-u-dowleh, son of Bai Sunqur. Within two years, he was beheaded by the order of his own eldest son, 'Abd al-Latif, while on his way to Mecca. Eventually, his reputation was rehabilitated by his relative, 'Abdullah (1450-1451), who placed Ulugh Beg's remains in the tomb of Timur in Samarkand, where they were found by archeologists in 1941.

The crater, Ulugh Beigh, on the Moon, was named after him by the German astronomer Johann Heinrich von Mädler on his 1830 map of the Moon.

See also

- Muslim scholars

- Ulugh Beg Observatory and Museum

ulughh

Notes

- ^ B.F. Manz, "Tīmūr Lang", in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Online Edition, 2006

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica, "Timur", Online Academic Edition, 2007. Quotation: "Timur was a member of the Turkicized Barlas tribe, a Mongol subgroup that had settled in Transoxania...

- ^ Hugh Thurston, Early Astronomy, (New York: Springer-Verlag), p. 194, ISBN 0-387-94107-X.

References

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Ulugh Beg", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Ulugh_Beg.html.

- 1839. L. P. E. A. Sedillot (1808–1875). Tables astronomiques d’Oloug Beg, commentees et publiees avec le texte en regard, Tome I, 1 fascicule, Paris. A very rare work, but referenced in the Bibliographie generale de l’astronomie jusqu’en 1880, by J.

- 1847. L. P. E. A. Sedillot (1808–1875). Prolegomenes des Tables astronomiques d’Oloug Beg, publiees avec Notes et Variantes, et precedes d’une Introduction. Paris: F. Didot.

- 1853. L. P. E. A. Sedillot (1808–1875). Prolegomenes des Tables astronomiques d’Oloug Beg, traduction et commentaire. Paris.

- Le Prince Savant annexe les étoiles, Frédérique Beaupertuis-Bressand, in Samarcande 1400-1500, La cité-oasis de Tamerlan : coeur d'un Empire et d'une Renaissance, book directed by Vincent Fourniau, éditions Autrement, 1995, ISSN 1157 - 4488.

- L'âge d'or de l'astronomie ottomane, Antoine Gautier, in L'Astronomie, (Monthly magazine created by Camille Flammarion in 1882), December 2005, volume 119.

- L'observatoire du prince Ulugh Beg, Antoine Gautier, in L'Astronomie, (Monthly magazine created by Camille Flammarion in 1882), October 2008, volume 122.

- Le recueil de calendriers du prince timouride Ulug Beg (1394–1449), Antoine Gautier, in Le Bulletin, n° spécial Les calendriers, Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales, juin 2007, pp. 117–123. d

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.- Jean-Marie Thiébaud, Personnages marquants d'Asie centrale, du Turkestan et de l'Ouzbékistan, Paris, éditions L'Harmattan, 2004. ISBN 2-7475-7017-7.

External links

- The observatory and memorial museum of Ulugbek

- Bukhara Ulugbek Madrasah

- Registan the heart of ancient Samarkand.

- Biography by School of Mathematics and Statistics University of St Andrews, Scotland

- Afghanland.com

- Legacy of Ulug Beg

Media related to Ulugh Beg at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ulugh Beg at Wikimedia Commons Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Ulugh Beg". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Ulugh Beg". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Ulugh BegPreceded by

Shah RukhTimurid Dynasty Succeeded by

'Abd al-LatifMathematics in medieval Islam Mathematicians 9th century10th centuryAbd al-Rahman al-Sufi · Abū al-Wafā' al-Būzjānī · Abū Ja'far al-Khāzin · Abū Kāmil Shujāʿ ibn Aslam · Abu'l-Hasan al-Uqlidisi · Abu-Mahmud Khojandi · Ahmad ibn Yusuf · Al-Nayrizi · Al-Saghani · Brethren of Purity · Ibn Sahl · Ibn Yunus · Ibrahim ibn Sinan · Muhammad ibn Jābir al-Harrānī al-Battānī · Sinan ibn Thabit · Al-Isfahani · Abu-Mahmud Khojandi · Nazif ibn Yumn · Abū Sahl al-Qūhī11th centuryAbū Ishāq Ibrāhīm al-Zarqālī · Abu Nasr Mansur · Abū Rayḥān al-Bīrūnī · Alhazen · Ibn Muʿādh al-Jayyānī · Al-Karaji · Al-Sijzi · Alī ibn Ahmad al-Nasawī · Avicenna · Ibn Tahir al-Baghdadi · Kushyar ibn Labban · Yusuf al-Mu'taman ibn Hud12th century13th centuryMuhyi al-Dīn al-Maghribī · Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī · Shams al-Dīn al-Samarqandī · Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī · Ibn al‐Ha'im al‐Ishbili · Ibn Abi al-Shukr14th centuryYaʿīsh ibn Ibrāhīm al-Umawī · Ibn al-Banna' al-Marrakushi · Ibn al-Shatir · Kamāl al-Dīn Fārisī · Al-Khalili · Qotb al-Din Shirazi · Ahmad al-Qalqashandi15th century16th centuryTreatises Concepts Alhazen's problemCenters Influences Influenced Categories:- 1390s births

- 1449 deaths

- Astronomers of medieval Islam

- Mathematicians of medieval Islam

- 15th-century mathematicians

- Medieval Persian astronomers

- Medieval Persian mathematicians

- Medieval Turkic mathematicians

- Monarchs of Persia

- Timurid monarchs

- Scientific instrument makers

- Gentleman scientists

- 15th-century astronomers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.