- Camille Flammarion

-

Camille Flammarion

Born Nicolas Camille Flammarion

February 26, 1842

Montigny-le-Roi, Haute-MarneDied June 3, 1925 (aged 83)

Juvisy-sur-OrgeRelatives Ernest Flammarion (1846-1936), brother Nicolas Camille Flammarion (26 February 1842—3 June 1925) was a French astronomer and author. He was a prolific author of more than fifty titles, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science fiction novels, and several works about Spiritism and related topics. He also published the magazine L'Astronomie, starting in 1882. He maintained a private observatory at Juvisy-sur-Orge, France.

Contents

Biography

Camille Flammarion was born in Montigny-le-Roi, Haute-Marne, France. He was the brother of Ernest Flammarion (1846–1936), founder of the Groupe Flammarion publishing house. He was a founder and the first president of the Société Astronomique de France, which originally had its own independent journal, BSAF (Bulletin de la Société astronomique de France), first published in 1887. In January, 1895, after 13 volumes of L'Astronomie and 8 of BSAF, the two merged, making L'Astronomie the Bulletin of the Societé. The 1895 volume of the combined journal was numbered 9, to preserve the BSAF volume numbering, but this had the consequence that volumes 9 to 13 of L'Astronomie can each refer to two different publications, five years apart of each other.[1]

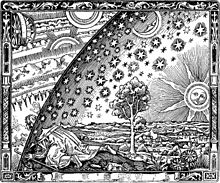

The "Flammarion engraving" first appeared in Flammarion's 1888 edition of L'Atmosphère. In 1907 he wrote that he believed that dwellers on Mars had tried to communicate with the Earth in the past.[2] He also believed in 1907 that a seven tailed comet was heading toward Earth.[3] In 1910 for the appearance of Halley's Comet, he believed the gas from the comet's tail "would impregnate [the Earth's] atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet."[4]

His second wife was Gabrielle Renaudot Flammarion, also a noted astronomer.

Flammarion died in Juvisy-sur-Orge.

Spiritism

Because of his scientific background, he approached spiritism and reincarnation from the viewpoint of the scientific method, writing, "It is by the scientific method alone that we may make progress in the search for truth. Religious belief must not take the place of impartial analysis. We must be constantly on our guard against illusions.".[5] He was chosen to speak at the funerals of Allan Kardec, codifier of Spiritism, on 2 April 1869, when he re-affirmed that "spiritism is not a religion but a science"

His spiritist studies also influenced some of his science fiction. In "Lumen", a human character meets the soul of an alien, able to cross the universe faster than light, that has been reincarnated on many different worlds, each with their own gallery of organisms and their evolutionary history. Other than that, his writing about other worlds adhered fairly closely to then current ideas in evolutionary theory and astronomy.

Legacy

He was the first to suggest the names Triton and Amalthea for moons of Neptune and Jupiter, respectively, although these names were not officially adopted until many decades later.[6]

Honors

Named after him

- Flammarion (lunar crater).

- Flammarion (crater on Mars).

- Asteroids: 1021 Flammario is named in his honour, and it is believed that 107 Camilla derives from Flammarion's first name. In addition, 154 Bertha commemorates his sister, Berthe Martin-Flammarion; 654 Zelinda his niece; and 87 Sylvia possibly his first wife, Sylvie Petiaux-Hugo Flammarion. 141 Lumen is named after Flammarion's book Lumen : Récits de l'infini; 286 Iclea for the heroine of his novel Uranie; and 605 Juvisia after Juvisy-sur-Orge, France, where his observatory was located

Quotations

"What intelligent being, what being capable of responding emotionally to a beautiful sight, can look at the jagged, silvery lunar crescent trembling in the azure sky, even through the weakest of telescopes, and not be struck by it in an intensely pleasurable way, not feel cut off from everyday life here on earth and transported toward that first stop on the celestial journeys? What thoughtful soul could look at brilliant Jupiter with its four attendant satellites, or splendid Saturn encircled by its mysterious ring, or a double star glowing scarlet and sapphire in the infinity of night, and not be filled with a sense of wonder? Yes, indeed, if humankind — from humble farmers in the fields and toiling workers in the cities to teachers, people of independent means, those who have reached the pinnacle of fame or fortune, even the most frivolous of society women — if they knew what profound inner pleasure await those who gaze at the heavens, then France, nay, the whole of Europe, would be covered with telescopes instead of bayonets, thereby promoting universal happiness and peace." — Camille Flammarion, 1880

"This end of the world will occur without noise, without revolution, without cataclysm. Just as a tree loses leaves in the autumn wind, so the earth will see in succession the falling and perishing all its children, and in this eternal winter, which will envelop it from then on, she can no longer hope for either a new sun or a new spring. She will purge herself of the history of the worlds. The millions or billions of centuries that she had seen will be like a day. It will be only a detail completely insignificant in the whole of the universe. Presently the earth is only an invisible point among all the stars, because, at this distance, it is lost through its infinite smallness in the vicinity of the sun, which itself is by far only a small star. In the future, when the end of things will arrive on this earth, the event will then pass completely unperceived in the universe. The stars will continue to shine after the extinction of our sun, as they already shone before our existence. When there will no longer be on the earth a sole concern to contemplate, the constellations will reign again in the noise as they reigned before the appearance of man on this tiny globule. There are stars whose light shone some millions of years before we arrived … The luminous rays that we receive actually then departed from their bosom before the time of the appearance of man on the earth. The universe is so immense that it appears immutable, and that the duration of a planet such as that of the earth is only a chapter, less than that, a phrase, less still, only a word of the universe’s history." — Camille Flammarion, Le Fin du Monde (The End of the World)

Works

- La pluralité des mondes habités (The Plurality of Inhabited Worlds), 1862.

- Real and Imaginary Worlds, 1865.

- God in nature, 1866.

- Lumen, 1867.

- Récits de l'infini, 1872.

- L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire, 1888.

- Astronomie populaire, 1880. His best-selling work, it was translated into English as Popular Astronomy in 1894.

- Les Étoiles et les Curiosités du Ciel, 1882. A supplement of the L'Astronomie Populaire works. An observer's handbook of its day.

- Uranie, 1890.

- La planète Mars et ses conditions d'habitabilité, 1892.

- La Fin du Monde (The End of the World), 1893, is a science fiction novel about a comet colliding with the Earth, followed by several million years leading up to the gradual death of the planet. It has recently been brought back into print as Omega: The Last Days of the World. It was adapted into a film in 1931 by Abel Gance.

- L’inconnu et les problèmes psychiques (published in English as: L’inconnu: The Unknown), 1900, a collection of psychic experiences.

References

- ^ Which l'Astronomie?

- ^ "Martians Probably Superior to Us; Camille Flammarion Thinks Dwellers on Mars Tried to Communicate with the Earth Ages Ago". New York Times. November 10, 1907. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9E03E5D8103EE033A25753C1A9679D946697D6CF. Retrieved 2009-11-14. "Prof. Lowell's theory that intelligent beings with constructive talents of a high order exist on the planet Mars has a warm supporter in M. Camille Flammarion, the well-known French astronomer, who was seen in his observatory at Juvisy, near Paris, by a New York Times correspondent. M. Flammarion had just returned from abroad, and was in the act of reading a letter from Prof. Lowell."

- ^ "Flammarion's Seven Tailed Comet". Nelson Evening Mail. 30 July 1907. http://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/cgi-bin/paperspast?a=d&d=NEM19070730.2.39. Retrieved 2009-11-15.

- ^ "Ten Notable Apocalypses That (Obviously) Didn’t Happen". Smithsonian magazine. November 12, 2009. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/Ten-Notable-Apocalypses-That-Obviously-Didnt-Happen.html. Retrieved 2009-11-14. "The New York Times reported that the noted French astronomer, Camille Flammarion believed the gas “would impregnate that atmosphere and possibly snuff out all life on the planet.”"

- ^ in "Death and Its Mystery", 1921, 3 volumes. Translated by Latrobe Carroll (1923, T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd. London: Adelphi Terrace.). Partial online version at Manifestations of the Dead in Spiritistic Experiments

- ^ Camille Flammarion

External links

- Works by Camille Flammarion at Project Gutenberg

- Atlas cèleste, Paris 1877 da www.atlascoelestis.com

Categories:- 1842 births

- 1925 deaths

- 19th-century astronomers

- 20th-century astronomers

- French astronomers

- Apocalypticists

- Spiritism

- French balloonists

- French science fiction writers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.