- Compass rose

-

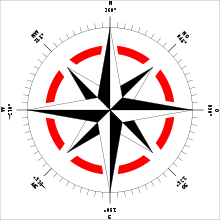

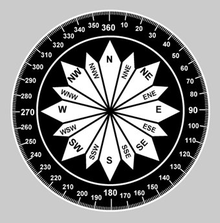

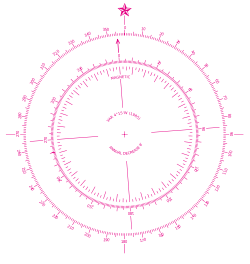

A common compass rose as is found on a nautical chart showing both true and magnetic north with magnetic declination

A common compass rose as is found on a nautical chart showing both true and magnetic north with magnetic declination

A compass rose, sometimes called a windrose, is a figure on a compass, map, nautical chart or monument used to display the orientation of the cardinal directions — North, East, South and West - and their intermediate points. It is also the term for the graduated markings found on the traditional magnetic compass. Today, the idea of a compass rose is found on, or featured in, almost all navigation systems, including nautical charts, non-directional beacons (NDB), VHF omnidirectional range (VOR) systems, global-positioning systems (GPS), and similar equipment and devices.

Contents

Compass Points

The compass rose is an old design element found on compasses, maps and even monuments (e.g. the Tower of the Winds in Athens, the pavement in Dougga, Tunis, during Roman times)[1] to show cardinal directions and frequently intermediate direction. The "rose" term arises from the fairly ornate figures used with early compasses. Older sources sometimes use the term "compass star", or stella maris ("star of the sea"), to refer to the compass rose.

Early forms of the compass rose were known as wind roses, since no differentiation was made between a directional point and the wind which emanated from that direction.[2] (Today, the term "wind rose" is often reserved for the object used by meteorologists to depict wind frequencies from different directions at a location.[3][4])

The modern compass rose has eight principal winds. Listed clockwise, these are:

Compass Point Abbr. Direction Traditional Wind North N 0° Tramontane North-East NE 45° Greco or Gregale East E 90° Levante South-East SE 135° Scirocco South S 180° Ostro or Mezzogiorno South-West SW 225° Libeccio or Garbino West W 270° Ponente North-West NW 315° Maestro or Mistral Although modern compasses uses the names of the eight principal directions (N, NE, E, SE, etc.), older compasses use the traditional Italianate wind names of Medieval origin (Tramontana, Greco, Levante, etc.)

16-point roses are constructed by bisecting the angles to come up with intermediate compass points, known as half-winds, at 221⁄2° each. The names of the half-winds are simply combinations of the principal winds to either side, e.g. North-northeast (NNE), East-northeast (ENE), etc.

32-point compass roses are constructed by bisecting these angles, and coming up with quarter-winds at 111⁄4° angles. Quarter-wind names are constructed with the names "X by Y", which can be read as "one quarter wind from X toward Y", e.g. North-by-east (NbE) is one quarter wind from North towards East, Northeast-by-north (NEbN) is one quarter wind from Northeast toward North.

Naming all 32 points on the rose is called boxing the compass.

The 32-point rose has the uncomfortable number of 111⁄4° between points, but is easily found by halving divisions and may have been easier for those not using a 360° circle. Using gradians, of which there are 400 in a circle,[5] the sixteen-point rose will have twenty-five gradians per point.

History

Linguistic athropological studies have shown that most peoples have four points of cardinal direction. The directional names are derived either from (1) locally-specific geographic features ("towards the hills", "towards the sea"); (2) celestial bodies (especially the sun); (3) atmospheric features (winds, temperature); (4) application of generic directions to cardinal directions (e.g. uptown/downtown for north/south).[6] Mobile populations tend to adopt sunrise and sunset for East and West, and the direction from where different winds blow to denote North and South.

Classical compass rose

The ancient Greeks originally maintained distinct and separate systems of points and winds. The four Greek cardinal points (arctos, anatole, mesembria and dusis) were based on celestial bodies and used for orientation. The four Greek winds (Boreas, Notos, Eurus, Zephyrus) were confined to meteorology. Nonetheless, both systems were gradually conflated, and wind names came to eventually denote cardinal directions as well.[7]

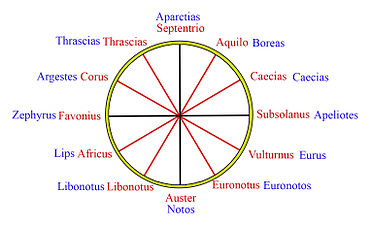

In his meteorological studies, Aristotle identified ten distinct winds: two north-south winds (Aparctias, Notos) and three sets of east-west winds blowing from different latitudes - the Arctic circle (Meses, Thrascias), the summer solstice horizon (Caecias, Argestes), the equinox (Apeliotes, Zephyrus) and the winter solstice (Eurus, Lips). However, Aristotle's system was asymmetric. To restore balance, Timosthenes of Rhodes added two more winds to produce the classical 12-wind rose, and began using the winds to denote geographical direction in navigation. Eratosthenes deducted two winds from Aristotle's system, to produce the classical 8-wind rose.

The Romans (e.g. Seneca, Pliny) adopted the Greek 12-wind system, and replaced its names with Latin equivalents, e.g. Septentrio, Subsolanus, Auster, Favonius, etc. Uniquely, Vitruvius came up with a 24-wind rose.

According to the chronicler Einhard (c.830), the Frankish king Charlemagne himself came up with his own names for the classical 12 winds.[8] He named the four cardinal winds on the roots Nord (etymology uncertain, could be "wet", meaning from the rainy lands), Ost (shining place, sunrise), Sund (sunny lands) and Vuest (dwelling place, meaning evening). Intermediate winds were constructed as simple compound names of these four (e.g. "Nordostdroni", the "northeasterly" wind). These Carolingian names are the source of the modern compass point names found in nearly all modern west European languages. (e.g. North, East, South and West in English; Nord, Est, Sud, Ouest in French, etc.)

The following table gives a rough equivalence of the classical 12-wind rose with the modern compass directions (Note: the directions are imprecise since it is not clear at what angles the classical winds are supposed to be with each other; some have argued that they should be equally spaced at 30 degrees each; for more details, see the article on Classical compass winds).

Wind Greek Roman Frankish N Aparctias

ὰπαρκτίαςSeptentrio Nordroni NNE Meses (μέσης)

or Boreas (βoρέας)Aquilo Nordostroni NE Caicias

(καικίας)Caecias Ostnordroni E Apeliotes

(ὰπηλιώτης)Subsolanus Ostroni SE Eurus

(εΰρος)Vulturnus Ostsundroni SSE Euronotus

(εὺρόνοtος)Euronotus Sundostroni S Notos

(νόtος)Auster Sundroni SSW Libonotos

(λιβόνοtος)Libonotus

or AustroafricusSundvuestroni SW Lips

(λίψ)Africus Vuestsundroni W Zephyrus

(ζέφυρος)Favonius Vuestroni NW Argestes

(ὰργέστης)Corus Vuestnordroni NNW Thrascias

(θρασκίας)Thrascias

or CirciusNordvuestroni Sidereal compass rose

The "sidereal" compass rose demarcates the compass points by the position of stars in the night sky, rather than winds. Arab navigators in the Red Sea and the Indian Ocean, who depended on celestial navigation, were using a 32-point sidereal compass rose before the end of the 10th C.[9][10][11][12][13] In the northern hemisphere, the steady Pole Star (Polaris) was used for the N-S axis; the less-steady Southern Cross had to do for the southern hemipshere, as the southern pole star, Sigma Octantis, is too dim to be easily seen from Earth with the naked eye. The other thirty points on the sidereal rose were determined by the rising and setting positions of fifteen bright stars of the northern hemisphere. Reading from North to South, in their rising positions, these are:[14]

Point Star N Polaris NbE "the Guards" (Ursa Minor) NNE Alpha Ursa Major NEbN Alpha Cassiopeiae NE Capella NEbE Vega ENE Arcturus EbN the Pleiades E Altair EbS Orion's belt ESE Sirius SEbE Beta Scorpionis SE Antares SEbS Alpha Centauri SSE Canopus SbE Achenar The western half of the rose would be the same stars in their setting position. The true position of these stars is only approximate to their theoretical equidistant rhumbs on the sidereal compass. As a practical matter, as sometimes these stars were not visible, or too high to be convenient, there were "alternate" stars nearby that could be used instead.[15]

The Mariner's compass rose

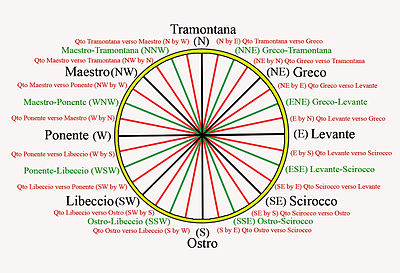

In Europe, the Classical 12-wind system continued to be taught in academic settings during the Medieval era, but seafarers in the Mediterranean Sea came up with their own distinct 8-wind system. The mariners used names derived from the Mediterranean lingua franca - the Italian-tinged patois among Medieval sailors, composed principally of Ligurian, mixed with Venetian, Sicilian, Provençal, Catalan, Greek and Arabic terms from around the Mediterranean basin.

- (N) Tramontana

- (NE) Greco (or Bora)

- (E) Levante

- (SE) Scirocco (or Exaloc)

- (S) Ostro (or Mezzogiorno)

- (SW) Libeccio (or Garbino)

- (W) Ponente

- (NW) Maestro (or Mistral)

The exact origin of the mariner's eight-wind rose is obscure. Only two of its point names (Ostro, Libeccio) have Classical etymologies, the rest of the names seem to be autonomously derived. Two Arabic words stand out: Scirocco (SE) from al-Sharq (east) and the variant Garbino (SW), from al-Gharb (west). This suggests the mariner's rose was probably acquired by southern Italian seafarers not from their classical Roman ancestors, but rather from Arab-Norman Sicily in the 11th-12th C.[16] The coasts of the Maghreb and Mashriq are SW and SE of Sicily respectively; the Greco (a NE wind), reflects the position of Byzantine-held Calabria-Apulia to the northeast of Arab Sicily, while the Maestro (a NW wind) is a reference to the Mistral wind that blows from the southern French coast towards northwest Sicily.

The 32-point compass used for navigation in the Mediterranean Sea by the 14th C., had increments of 111⁄4° between points. Only the eight main winds (N, NE, E, SE, S, SW, W, NW) were given special names. The eight half-winds just combined the names of the two main winds, e.g. Greco-Tramontana for NNE, Greco-Levante for ENE, and so on. Quarter-winds were more cumbersomely phrased, with the closest main wind named first and the other main wind second, e.g. "Quarto di Tramontana verso Greco" (literally, "one quarter wind from North towards Northeast", i.e. North by East), and "Quarto di Greco verso Tramontana" ("one quarter wind from NE towards North", i.e. Northeast by North). Boxing the compass (naming all 32 winds) was expected of all Medieval mariners.

Depiction on Nautical Charts

First ornate compass rose depicted on a map, from the Catalan Atlas (1375), with the Pole Star as north mark.

First ornate compass rose depicted on a map, from the Catalan Atlas (1375), with the Pole Star as north mark.

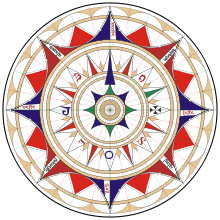

In the earliest Medieval portolan charts of the 14th Century, compass roses were depicted as mere collections of color-coded compass rhumb lines: black for the eight main winds, green for the eight half-winds and red for the sixteen quarter-winds.[17] The average portolan chart had sixteen such roses (or confluence of lines), spaced out equally around the circumference of a large implicit circle.

The cartographer Cresques Abraham of Majorca, in his Catalan Atlas of 1375, was the first to draw an ornate compass rose on a map. By the end of the 15th C, Portuguese cartographers began drawing multiple ornate compass roses throughout the chart, one upon each of the sixteen circumference roses (unless the illustration conflicted with coastal details).[18]

Medieval Italian cartographers typically had a simple arrowhead or circumflex-hatted T (an allusion to the compass needle) to designate the north, while the Majorcan cartographic school typically used a stylized Pole Star for its northmark.[19] The use of the fleur-de-lis as northmark was introduced by Pedro Reinel, and has become customary in later compass roses. Old compass roses also often used a Christian cross at Levante (E), indicating the direction of Jerusalem from the point of view of the Mediterranean sea.[2]

The twelve Classical winds (or a subset of them) were also sometimes depicted on portolan charts, albeit not on a compass rose, but rather separately on small disks or coins on the edges of the map.

The Arab sailors navigated by a 32-point compass rose during the Middle Ages.[20][not in citation given]

The compass rose was also depicted on traverse boards used to record compass headings.

Modern depictions

The contemporary compass rose appears as two rings, one smaller and set inside the other. The outside ring denotes true cardinal directions while the smaller inside ring denotes magnetic cardinal directions. True north refers to the geographical location of the north pole while magnetic north refers to the direction towards which the north pole of a magnetic object (as found in a compass) will point. The angular difference between true and magnetic north is called variation, which varies depending on location.[21] The angular difference between magnetic heading and compass heading is called deviation which varies by vessel and its heading.

The Compass Rose is used as the symbol of the worldwide Anglican Communion of churches.[22]

In popular culture

- HMS Compass Rose is a fictional Royal Navy Flower class corvette in the novel The Cruel Sea.

- In the adventure game, Beyond Zork, a compass rose is a flower that can control the direction of the wind.

- The Compass Rose is the name of a significant tavern in Mercedes Lackey's Valdemar fantasy novels.

- An 8-point compass rose is a prominent feature in the logo of the Seattle Mariners Major League Baseball club.

- A compass rose was the logo of Varig, the largest airline in Brazil for many decades until its bankruptcy in 2006.

Usage

- NATO symbol uses four point star

- Hong Kong Correctional Services's crest uses four point star

See also

- Windrose

References

- ^ Martín-Gil, F.J; Martín-Ramos, P.; Martín-Gil, J. (2005): A cryptogram in the compass roses of the Majorcan portolan charts from the Messina-Naples mapmakers school.- Almogaren XXXVI (Institutum Canarium), Wien, 285-295.

- ^ a b Dan Reboussin (2005). Wind Rose. University of Florida. Retrieved on 2009-04-26.

- ^ "The wind rose and the classical winds" (2001) University of Florida. Retrieved on 2010-07-29.

- ^ Glossary of Meteorology (2009). Wind rose. American Meteorological Society. Retrieved on 2009-04-25.

- ^ Patrick Bouron (2005). Cartographie: Lecture de Carte. Institut Géographique National. p. 12. http://webdav-noauth.unit-c.fr/files/perso/pbarbier/cours_unit/Elements_de_base_de_la_cartographie.pdf. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- ^ Brown, C.H. (1983) "Where do Cardinal Direction Terms Come From?", Anthropological Linguistics, Vol. 25 (2), p. 121-61.

- ^ D'Avezac, M.A.P. (1874) Aperçus historiques sur la rose des vents: lettre à Monsieur Henri Narducci. Rome: Civelli

- ^ Einhard, Vita Karoli Imp., [Lat: (Eng.(p.22)(p.68)

- ^ Saussure, L. de (1923) "L'origine de la rose des vents et l'invention de la boussole", Archives des sciences physiques et naturelles, vol. 5, no.2 & 3, pp.149-81 and 259-91.

- ^ Taylor, E.G.R. (1956) The Haven-Finding Art: A history of navigation from Odysseus to Captain Cook, 1971 ed., London: Hollis and Carter., p.128-31.

- ^ Tolmacheva, M. (1980) "On the Arab System of Nautical Orientation", Arabica, vol. 27 (2), p.180-92.

- ^ Tibbets, G.R. (1971) Arab Navigation in the Indian Ocean before the coming of the Portuguese, London: Royal Asiatic Society.

- ^ J. Lagan (2005) The Barefoot Navigator: Navigating with the skills of the ancients. Dobbs Ferry, NY: Sheridan House.

- ^ List comes from Tolmacheva (1980:p.183), based "with some reservations" on Tibbets (1971: p.296, n.133). The sidereal rose given in Lagan (2005: p.66) has some differences, e.g. placing Orion's belt in East and Altair in EbN.

- ^ Tomacheva (1980: p.184); Lagan (2006: p.66)

- ^ Taylor, E.G. R. (1937) "The 'De Ventis' of Matthew Paris", Imago Mundi, vol. 2, p. 25.

- ^ Wallis, H.M. and J.H. Robinson, editors (1987) Cartographical Innovations: an international handbook of mapping terms to 1900. London: Map Collector Publications.

- ^ A.E. Nordenskiöld (1896) "Résumé of an Essay on the Early History of Charts and Sailing Directions", Report of the Sixth International Geographical Congress: held in London, 1895. London: J. Murray. (p.693)

- ^ Winter, Heinrich (1947) "On the Real and the Pseudo-Pilestrina Maps and Other Early Portuguese Maps in Munich", Imago Mundi, vol. 4,p.25-27.

- ^ G. R. Tibbetts (1973), "Comparisons between Arab and Chinese Navigational Techniques", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 36 (1), p. 97-108 [105-106].

- ^ John Rousmaniere, Mark Smith (1999). The Annapolis book of seamanship. Simon and Schuster. p. 233. ISBN 9780684854205. http://books.google.com/books?id=xRqzoX04v5AC&pg=PA233&lpg=PA233&dq=compass+variation+book&source=bl&ots=RQOP6i4YkC&sig=7wi8b-sx9EAESaeQC55aNInCA6c&hl=en&ei=_88VTtLIDqHb0QHvsrkv&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CCsQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=compass%20variation%20book&f=false. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- ^ "About the Compass Rose Society"

External links

- Origins of the Compass Rose

- The Rose of the Winds - An example of a rose with 26 directions.

- Compass Rose of Piedro Reinel, 1504 - an example of a 32-point rose with cross for east (the Christian Holy Land) and fleur-di-lis for north.[dead link]

- The Compass Rose in St. Peter's Square

- Brief compass rose history info

- Floor Compass Roses

- Quilting Patterns Inspired by Compass Rose

- Compass Rose in Stained Glass

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.