- Nicolae Ceaușescu

-

For other people named "Ceauşescu", see Ceauşescu (disambiguation).The title of this article contains the character ș. Where it is unavailable or not desired, the name may be represented as Nicolae Ceausescu.

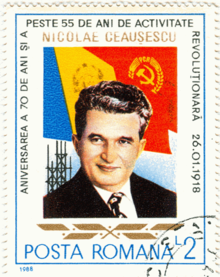

Nicolae Ceaușescu

General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party In office

22 March 1965 – 22 December 1989Vice President Elena Ceaușescu (his wife) Preceded by Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej Succeeded by party abolished 1st President of the State Council In office

9 December 1967 – 28 March 1974Preceded by Chivu Stoica Succeeded by Himself as President of Romania President of Romania In office

28 March 1974 – 22 December 1989Preceded by Himself as President of the State Council Succeeded by Ion Iliescu Personal details Born 26 January 1918

Scornicești, Olt, RomaniaDied 25 December 1989 (aged 71)

Târgoviște, Dâmbovița, RomaniaNationality Romanian Political party Communist Party of Romania Spouse(s) Elena Ceaușescu (m. 1946–1989) Children Valentin Ceaușescu, Zoia Ceaușescu, Nicu Ceaușescu Religion None (atheist) Signature

Nicolae Ceaușescu (Romanian pronunciation: [nikoˈla.e t͡ʃe̯a.uˈʃesku]; 26 January 1918 – 25 December 1989) was a Romanian Communist politician. He was Secretary General of the Romanian Communist Party from 1965 to 1989, and as such was the country's second and last Communist leader. He was also the country's head of state from 1967 to 1989.

His rule was marked in the first decade by an open policy towards Western Europe and the United States, which deviated from that of the other Warsaw Pact states during the Cold War. He continued a trend first established by his predecessor, Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, who had tactfully coaxed the Soviet Union into withdrawing its troops from Romania in 1958.[1]

Ceauşescu's second decade was characterized by an increasingly brutal and repressive regime—by some accounts, the most rigidly Stalinist regime in the Soviet bloc. It was also marked by a ubiquitous personality cult, nationalism and a deterioration in foreign relations with the Western powers as well as the Soviet Union. Ceaușescu's government was overthrown in the December 1989 revolution, and he and his wife were executed following a televised and hastily organised two-hour court session.[2]

Contents

Early life and career

Captured in 1936 when he was 18 years old, and imprisoned for two years at Doftana Prison for anti-fascist activities.

Captured in 1936 when he was 18 years old, and imprisoned for two years at Doftana Prison for anti-fascist activities.

Born in the village of Scornicești, Olt County, Ceaușescu moved to Bucharest at the age of 11 to work in factories. He was the son of a peasant (see Ceaușescu family for descriptions of his parents and siblings.) He joined the then-illegal Communist Party of Romania in early 1932 and was first arrested, in 1933, for street fighting during a strike. He was arrested again, in 1934, first for collecting signatures on a petition protesting the trial of railway workers and twice more for other similar activities. These arrests earned him the description "dangerous communist agitator" and "active distributor of communist and anti-fascist propaganda" on his police record. He then went underground, but was captured and imprisoned in 1936 for two years at Doftana Prison for anti-fascist activities.[3]

While out of jail in 1940, he met Elena Petrescu, whom he married in 1946 and who would play an increasing role in his political life over the years. He was arrested and imprisoned again in 1940. In 1943, he was transferred to Târgu Jiu internment camp where he shared a cell with Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, becoming his protégé. After World War II, when Romania was beginning to fall under Soviet influence, he served as secretary of the Union of Communist Youth (1944–1945).[3]

After the Communists seized power in Romania in 1947, he headed the Ministry of Agriculture, then served as Deputy Minister of the Armed Forces under Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej. In 1952, Gheorghiu-Dej brought him onto the Central Committee months after the party's "Muscovite faction" led by Ana Pauker had been purged. In 1954, he became a full member of the Politburo and eventually rose to occupy the second-highest position in the party hierarchy.[3]

Leadership of Romania

Meeting between US president Richard Nixon, US vice president Gerald Ford and Nicolae Ceauşescu in 1973

Meeting between US president Richard Nixon, US vice president Gerald Ford and Nicolae Ceauşescu in 1973

Ceauşescu is greeted by King Juan Carlos I of Spain in Madrid, 1979

Ceauşescu is greeted by King Juan Carlos I of Spain in Madrid, 1979

Ceaușescu was not the obvious successor to Gheorghiu-Dej when he died on 19 March 1965, despite his closeness to the longtime leader. However, amid widespread infighting among older and more connected officials, the Politburo turned to Ceaușescu as a compromise candidate.[4] He was elected general secretary on March 22, three days after Gheorghiu-Dej's death. One of his first acts was to change the name of the party from the Romanian Workers' Party back to the Communist Party of Romania, and declare the country the Socialist Republic of Romania rather than a People's Republic. In 1967, he consolidated his power by becoming president of the State Council.

Initially, Ceaușescu became a popular figure in Romania and also in the Western World, due to his independent foreign policy, challenging the authority of the Soviet Union. In the 1960s, he eased press censorship and ended Romania's active participation in the Warsaw Pact (though Romania formally remained a member); he refused to take part in the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces, and actively and openly condemned that action. He even traveled to Prague a week before the invasion to offer moral support to his Czechoslovak counterpart, Alexander Dubcek. Although the Soviet Union largely tolerated Ceaușescu's recalcitrance, his seeming independence from Moscow earned Romania maverick status within the Eastern Bloc.[4]

During the following years Ceaușescu pursued an open policy towards the United States and Western Europe. Romania was the first Communist country to recognize West Germany, the first to join the International Monetary Fund, and the first to receive a US President, Richard Nixon.[5] In 1971 Romania became a member of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Romania and Yugoslavia were also the only East European countries that entered into trade agreements with the European Economic Community before the fall of the Communist bloc.[6]

A series of official visits to Western countries (including the US, France, United Kingdom, Spain) helped Ceaușescu to present himself as a reforming Communist, pursuing an independent foreign policy within the Soviet Bloc. Also he became eager to be seen as an enlightened international statesman, able to mediate in international conflicts and to gain international respect for Romania.[7] Ceaușescu negotiated in international affairs, such as the opening of US relations with China in 1969 and the visit of Egyptian president Anwar Sadat to Israel in 1977. Also Romania was the only country in the world to maintain normal diplomatic relations with both Israel and the PLO.[8]

The 1966 decree

In 1966, the Ceaușescu regime, in an attempt to boost the country's population, made abortion illegal, and introduced other policies to reverse the very low birth rate and fertility rate. Mothers of at least five children would be entitled to significant benefits, while mothers of at least ten children were declared heroine mothers by the Romanian state. However, few women ever sought this status; instead, the average Romanian family during the time had two to three children (see Demographics of Romania).[9] Furthermore, a considerable number of women either died or were maimed during clandestine abortions.[10]

The government also targeted rising divorce rates and made divorce much more difficult - it was decreed that a marriage could be dissolved only in exceptional cases. By the late 1960s, the population began to swell. In turn, a new problem was created by child abandonment, which swelled the orphanage population (see Cighid). Transfusions of untested blood led to Romania accounting for many of Europe's paediatric HIV/AIDS cases at the turn of the century despite having a population that only makes up around 3% of Europe.[11][12]

July Theses

Main article: July ThesesCeaușescu visited the People's Republic of China, North Korea, and North Vietnam in 1971. He took great interest in the idea of total national transformation as embodied in the programs of North Korea's Juche and China's Cultural Revolution. He was also inspired by the personality cults of North Korea's Kim Il-sung and China's Mao Zedong. Shortly after returning home, he began to emulate North Korea's system. North Korean books on Juche were translated into Romanian and widely distributed in the country.

On 6 July 1971, he delivered a speech before the Executive Committee of the PCR. This quasi-Maoist speech, which came to be known as the July Theses, contained seventeen proposals. Among these were: continuous growth in the "leading role" of the Party; improvement of Party education and of mass political action; youth participation on large construction projects as part of their "patriotic work"; an intensification of political-ideological education in schools and universities, as well as in children's, youth and student organizations; and an expansion of political propaganda, orienting radio and television shows to this end, as well as publishing houses, theatres and cinemas, opera, ballet, artists' unions, promoting a "militant, revolutionary" character in artistic productions. The liberalisation of 1965 was condemned and an index of banned books and authors was re-established.

The Theses heralded the beginning of a "mini cultural revolution" in Romania, launching a Neo-Stalinist offensive against cultural autonomy, reaffirming an ideological basis for literature that, in theory, the Party had hardly abandoned. Although presented in terms of "Socialist Humanism", the Theses in fact marked a return to the strict guidelines of Socialist Realism, and attacks on non-compliant intellectuals. Strict ideological conformity in the humanities and social sciences was demanded. Competence and aesthetics were to be replaced by ideology; professionals were to be replaced by agitators; and culture was once again to become an instrument for political-ideological propaganda and anti-revisionism.

In 1974, Ceaușescu became President of the Socialist Republic of Romania, further consolidating his power. He continued to follow an independent policy in foreign relations—for example, in 1984, Romania was one of only three communist states (the others being the People's Republic of China, and Yugoslavia) to take part in the American-organized 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles.

Also, the Socialist Republic of Romania was the first of the Eastern bloc to have official relations with the Western bloc and European Community: an agreement including Romania in the Community's Generalised System of Preferences was signed in 1974 and an Agreement on Industrial Products was signed in 1980. On 4 April 1975, Ceaușescu visited Japan and met with Hirohito.

Pacepa defection

In 1978, Ion Mihai Pacepa, a senior member of the Romanian political police (Securitate), defected to the United States. A 2-star general, he was the highest ranking defector from the Eastern Bloc in the history of the Cold War. His defection was a powerful blow against the regime, forcing Ceauşescu to overhaul the architecture of the Securitate. Pacepa's 1986 book, Red Horizons: Chronicles of a Communist Spy Chief (ISBN 0-89526-570-2), claims to expose details of Ceaușescu's regime, such as massive spying on American industry and elaborate efforts to rally Western political support.

After Pacepa's defection, the country became more isolated and economic growth faltered. Ceaușescu's intelligence agency became subject to heavy infiltration by foreign intelligence agencies[citation needed] and he started to lose control of the country. He tried several reorganizations in a bid to get rid of old collaborators of Pacepa, but to no avail[citation needed].

Foreign debt

Ceaușescu's political independence from the Soviet Union and his protest against the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968 drew the interest of Western powers, who briefly believed he was an anti-Soviet maverick and hoped to create a schism in the Warsaw Pact by funding him. Ceaușescu did not realise that the funding was not always favorable. Ceaușescu was able to borrow heavily (more than $13 billion) from the West to finance economic development programs, but these loans ultimately devastated the country's finances. In an attempt to correct this, Ceaușescu decided to repay Romania's foreign debts. He organised a referendum and managed to change the constitution, adding a clause that barred Romania from taking foreign loans in the future. The referendum yielded a nearly unanimous "yes" vote.

In the 1980s, Ceaușescu ordered the export of much of the country's agricultural and industrial production in order to repay its debts. The resulting domestic shortages made the everyday life of Romanians a fight for survival as food rationing was introduced and heating, gas and electricity black-outs became the rule. During the 1980s, there was a steady decrease in the living standard, especially the availability and quality of food and general goods in stores. During this time, Ceaușescu shut down all radio stations outside of the capital, and limited television to one channel broadcasting only two hours a day. The official explanation was that the country was paying its debts and people accepted the suffering, believing it to be for a short time only and for the ultimate good.[citation needed]

The debt was fully paid in summer 1989, shortly before Ceaușescu was overthrown, but heavy exports continued until the revolution in December.

Tensions

By early 1989, Ceaușescu was showing signs of complete denial of reality. While the country was going through extremely difficult times with long bread queues in front of empty food shops, he was often shown on state TV entering stores filled with food supplies, visiting large food and arts festivals, while praising the "high living standard" achieved under his rule.

Special contingents of food deliveries would fill stores before his visits, and well-fed cows would even be transported across the country in anticipation of his visits to farms. In at least one emergency, he inspected (and approved) a display of Hungarian produce, which apart from some corn and several melons, was largely constructed of painted plastic and/or polystyrene. Meanwhile, staples such as flour, eggs, butter and milk were difficult to find and most people started to depend on small gardens grown either in small city alleys or out in the country. In late 1989, daily TV broadcasts showed lists of CAPs (kolkhozes, collective farms) with alleged record harvests, in blatant contradiction to the shortages experienced by the average Romanian at the time.

Some Romanians, believing that Ceaușescu was not aware of what was going on in the country outside of Bucharest, attempted to hand him petitions and complaint letters during his many visits around the country. However, each time he got a letter, he would immediately pass it on to members of his security. Whether or not Ceaușescu ever read any of these letters will probably remain unknown. It was common knowledge that people attempting to hand letters directly to Ceaușescu risked adverse consequences[citation needed], courtesy of the Securitate. People were strongly discouraged from talking to him directly[citation needed] and there was a general sense that morale in Romania had reached an overall low.

Revolution

Main article: Romanian Revolution of 1989In November 1989, the XIVth Congress of the Romanian Communist Party (PCR) saw Ceaușescu, then aged 71, re-elected for another five years as leader of the PCR. But the following month, Ceaușescu's regime collapsed after a series of violent events in Timișoara and Bucharest in December 1989.

Timișoara

Demonstrations in the city of Timișoara were triggered by the government-sponsored attempt to evict László Tőkés, an ethnic Hungarian pastor, accused by the government of inciting ethnic hatred. Members of his ethnic Hungarian congregation surrounded his apartment in a show of support.

Romanian students spontaneously joined the demonstration, which soon lost nearly all connection to its initial cause and became a more general anti-government demonstration. Regular military forces, police and Securitate fired on demonstrators on 17 December 1989, killing and wounding many. On 18 December 1989, Ceaușescu departed for a state visit to Iran, leaving the duty of crushing the Timișoara revolt to his subordinates and his wife. Upon his return to Romania on the evening of 20 December, the situation became even more tense, and he gave a televised speech from the TV studio inside Central Committee Building (CC Building), in which he spoke about the events at Timișoara in terms of an "interference of foreign forces in Romania's internal affairs" and an "external aggression on Romania's sovereignty".

The country, which had little or no information of the Timișoara events from the national media, learned about the Timișoara revolt from western radio stations such as Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, and by word of mouth. On the next day, 21 December, a mass meeting was staged. Official media presented it as a "spontaneous movement of support for Ceaușescu", emulating the 1968 meeting in which Ceaușescu had spoken against the invasion of Czechoslovakia by Warsaw Pact forces.

Overthrow

The mass meeting of 21 December, held in what is now Revolution Square, began like many of Ceauşescu's speeches over the years. With the usual Marxist-Leninist "wooden language", Ceaușescu delivered a litany of the achievements of the "socialist revolution" and Romanian "multi-laterally developed socialist society".

However, he'd seriously misjudged the crowd's mood. Several people began jeering, booing and whistling at him. Others began chanting "Ti-mi-șoa-ra! Ti-mi-șoa-ra!" Ceaușescu's uncomprehending facial expression as the crowd began to boo and heckle him remains one of the defining moments of the collapse of Communism in Eastern Europe. He tried to silence them by raising his right hand, and when that didn't work, offered them a raise of 100 lei per month.[4] Failing to control the crowds, the Ceaușescus finally took cover inside the building, where they remained until the next day. The rest of the day saw an open revolt of the Bucharest population, which had assembled in University Square and confronted the police and army at barricades. The unarmed rioters, however, were no match for the military apparatus concentrated in Bucharest, which cleared the streets by midnight and arrested hundreds of people in the process. Nevertheless, these seminal events are regarded to this day as the de facto revolution.

Although the television broadcasts of the "support meeting" and subsequent events had been interrupted, Ceaușescu's reaction to the events had already been imprinted on the country's collective memory. By the morning of 22 December, the rebellion had already spread to all major cities across the country. The suspicious death of Vasile Milea, the defense minister (later confirmed as a suicide), was announced by the media. Immediately thereafter, Ceaușescu presided over the CPEx (Political Executive Committee) meeting and assumed the leadership of the army.

However, believing that Milea had been murdered, the rank-and-file soldiers went over virtually en masse to the revolution. Ceaușescu made a desperate attempt to address the crowd gathered in front of the Central Committee building. However, the people in the square began throwing rocks and other projectiles at him, forcing him to take refuge in the building once more. One group of protesters forced open the doors of the building, by now left unprotected. They managed to overpower Ceaușescu's bodyguards and rushed through his office and onto the balcony. Although they didn't know it, they were only a few meters from Ceaușescu, who was trapped in an elevator. He, Elena and four others managed to get to the roof and escaped by helicopter, only seconds ahead of a group of demonstrators who had followed them there.[4] Shortly afterward, the PCR disappeared.

During the course of the revolution, the western press published estimates of the number of people killed by the Securitate in attempting to support Ceaușescu and quash the rebellion. The count increased rapidly until an estimated 64,000 fatalities were widely reported across front pages. The Hungarian military attaché expressed doubt regarding these figures, pointing out the unfeasible logistics of killing such a large number of people in such a short period of time. After Ceauşescu's death, hospitals across the country reported an actual death toll of less than 1,000, and probably much lower than that.[13]

Death

Ceaușescu and his wife Elena fled the capital with Emil Bobu and Manea Mănescu and headed, by helicopter, for Ceaușescu's Snagov residence, from where they fled again, this time for Târgoviște. Near Târgoviște they abandoned the helicopter, having been ordered to land by the army, which by that time had restricted flying in Romania's airspace. The Ceauşescus were held by the police while the policemen listened to the radio. They were eventually turned over to the army. On Christmas Day, 25 December, the two were tried in a brief show-trial and sentenced to death by a military court on charges ranging from illegal gathering of wealth to genocide, and were executed in Târgoviște. During the trial, Ceaușescu repeatedly denied the court's authority to try him, and asserted he was still legally president of Romania. The video of the trial shows that, after sentencing, they had their hands tied behind their backs and were led outside the building to be executed.

The Ceaușescus were executed by a firing squad consisting of elite paratroop regiment soldiers: Captain Ionel Boeru, Sergant-Major Georghin Octavian and Dorin-Marian Cirlan,[14] while reportedly hundreds of others also volunteered. The firing squad began shooting as soon as the two were in position against a wall. The firing happened too soon for the film crew covering the events to record it.[15] Before his sentence was carried out, Nicolae Ceaușescu sang "The Internationale" while being led up against the wall. After the shooting, the bodies were covered with canvas. The hasty show trial and the images of the dead Ceaușescus were videotaped and the footage promptly released in numerous western countries. Later that day, it was also shown on Romanian television.[16][17]

The Ceaușescus were the last people to be executed in Romania before the abolition of capital punishment on 7 January 1990.[18]

Their graves are located in Ghencea cemetery in Bucharest. They are buried on opposite sides of a path. The graves themselves are unassuming, but they tend to be covered in flowers and symbols of the regime. Some allege that the graves do not, in reality, contain their bodies. As of April 2007, their son Valentin has lost an appeal for an investigation into the matter. Upon his death in 1996, the elder son, Nicu, was buried nearby in the same cemetery. According to Jurnalul Național,[19] requests were made by the Ceaușescus' daughter Zoia and by supporters of their political views to move their remains to mausoleums or to purpose-built churches. These have been denied by the government. On 21 July 2010, forensic scientists exhumed the bodies of Nicolae and Elena to perform DNA tests.[20][21] Later it was determined that they were indeed the remains of Nicolae and Elena.[22]

Personality cult and authoritarianism

Ceaușescu created a pervasive personality cult, giving himself such titles as "Conducător" ("Leader") and "Geniul din Carpați" ("The Genius of the Carpathians"), with help from Proletarian Culture (Proletkult) poets such as Adrian Păunescu and Corneliu Vadim Tudor, and even had a king-like sceptre made for himself.

The most important day of the year during Ceaușescu's rule was his birthday, on 26 January—a day which saw Romanian media saturated with praise for him. According to historian Victor Sebestyen, it was one of the few days of the year when the average Romanian put on a happy face, since appearing miserable on this day was far too risky even to contemplate.[4]

Such excesses prompted the painter Salvador Dalí to send a congratulatory telegram to the "Conducător", in which he sarcastically congratulated Ceaușescu on his "introducing the presidential scepter." The Communist Party daily Scînteia published the message, unaware that it was a work of satire. To avoid new treason after Pacepa's defection, Ceaușescu also invested his wife Elena and other members of his family with important positions in the government, leading Romanians to joke that Ceaușescu was creating "socialism in one family".

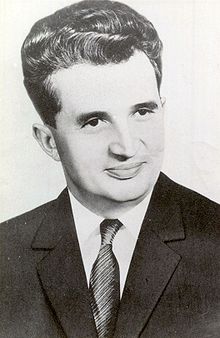

Not surprisingly, Ceaușescu was greatly concerned about his public image. Nearly all pictures of him showed him in his early 40s. Romanian state television was under strict orders to portray him in the best possible light. Additionally, producers had to take great care to make sure Ceaușescu's height—he was 5 feet 5 inches (1.65 m) tall—was never emphasized on screen. Consequences for breaking these rules were severe; one producer showed footage of Ceauşescu blinking and stuttering, and was banned for three months.[4]

Statesmanship

Ceaușescu's Romania was the only Communist country that retained diplomatic relations with Israel and did not sever diplomatic relations after Israel's launch of the Six-Day War in 1967 against neighboring states of Egypt, Jordan, and Syria. Ceaușescu made efforts to act as a mediator between the PLO and Israel.

He organised a successful referendum for reducing the size of the Romanian Army by 5% and held large rallies for peace.

Ceaușescu tried to play a role of influence and guidance to South American countries. He was a close ally and personal friend of dictator President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaïre. Relations were in fact not just state-to-state, but party-to-party between the MPR and the Romanian Communist Party. Many believe that Ceaușescu's death played a role in influencing Mobutu to "democratize" Zaïre in 1990.[23] Also, France granted Ceaușescu the Legion of Honour and in 1978 he became an Honorary British Knight[24] (GCB, stripped in 1989) in the UK, Elena Ceaușescu was arranged to be 'elected' to membership of a Science Academy in the USA; all of these, and more, were arranged by the Ceaușescus as a propaganda ploy through the consular cultural attachés of Romanian embassies in the countries involved.

Ceaușescu's Romania was the only Warsaw Pact country that did not sever diplomatic relations with Chile after Augusto Pinochet's coup.[25]

In August 1976, Nicolae Ceaușescu was the first high-level Romanian visitor to Bessarabia since World War II. In December 1976, at one of his meetings in Bucharest, Ivan Bodiul said that "the good relationship was initiated by Ceaușescu's visit to Soviet Moldavia."[26]

Other

His successor, Ion Iliescu, and Nicolae Ceaușescu in 1976

His successor, Ion Iliescu, and Nicolae Ceaușescu in 1976

Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu had three children, Valentin Ceaușescu (born 1948) a nuclear physicist, Nicu Ceaușescu (1951–1996) also a physicist, and a daughter Zoia Ceaușescu (1949–2006), who was a mathematician. After the death of his parents, Nicu Ceaușescu ordered the construction of an Orthodox church, the walls of which are decorated with portraits of his parents.[19]

Ceaușescu received the Danish Order of the Elephant, but this award was revoked on 23 December 1989 by the queen of Denmark, Margrethe II.

Ceaușescu was likewise stripped of his honorary GCB (Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath) by Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom on the day before his execution. Queen Elizabeth also returned the Romanian Order Ceaușescu had bestowed upon her.[27]

On his 70th birthday in 1988 Ceaușescu was decorated with the Karl-Marx-Orden by then Socialist Unity Party of Germany (SED) chief Erich Honecker; through this he was honoured for his rejection of Mikhail Gorbachev's reforms.

Praising the crimes of totalitarian regimes and denigrating their victims is forbidden by law in Romania; this includes the Ceaușescu regime. Dinel Staicu was imposed a 25,000 lei (approx. 9,000 United States dollars) fine for praising Ceaușescu and displaying his pictures on his private television channel (3TV Oltenia).[28]

Ceaușescu's last days in power were dramatized in a stage musical, The Fall of Ceaușescu, written and composed by Ron Conner. It premiered at the Los Angeles Theater Center in September 1995 and was attended by Ion Iliescu, the then president of Romania who had been visiting Los Angeles at the time.

One unresolved mystery that followed the deaths of Nicolae Ceaușescu pertains to Romania's Apollo 17 Goodwill Moon rock which was in Ceaușescu's possession at the time of his death, but has since disappeared. This moon rock was presented by the Nixon Administration to Romania and is said to be worth 5 million dollars on the black market.[29]

"Ceaușism"

While the term Ceaușism became widely used inside Romania, usually as a pejorative, it never achieved status in academia. This can be explained by the largely crude and syncretic character of the dogma. Ceaușescu attempted to include his views in mainstream Marxist theory, to which he added his belief in a "multilaterally developed socialist society" as a necessary stage between the Marxist concepts of Socialist and Communist societies (a critical view reveals that the main reason for the interval is the disappearance of the State and Party structures in Communism). A Romanian Encyclopedic Dictionary entry in 1978 underlines the concept as "a new, superior, stage in the socialist development of Romania [...] begun by the 1971–1975 Five-Year Plan, prolonged over several [succeeding and projected] Five-Year Plans".[30]

Ceaușism's main trait was a form of Romanian nationalism,[31] one which arguably propelled Ceaușescu to power in 1965, and probably accounted for the Party leadership gathered around Ion Gheorghe Maurer choosing him over the more orthodox Gheorghe Apostol. Although he had previously been a careful supporter of the official lines, Ceaușescu came to embody Romanian society's wish for independence after what many considered years of Soviet directives and purges, during and after the SovRom fiasco. He carried this nationalist option inside the Party, manipulating it against the nominated successor Apostol. This nationalist policy had more timid precedents:[32] for example, the Gheorghiu-Dej regime had overseen the withdrawal of the Red Army in 1958.

It had also engineered the publishing of several works that subverted the Russian and Soviet image, such as the final volumes of the official History of Romania, no longer glossing over traditional points of tension with Russia and the Soviet Union (even alluding to an unlawful Soviet presence in Bessarabia). In the final years of Gheorghiu-Dej's rule more problems were openly discussed, with the publication of a collection of Karl Marx texts that dealt with Romanian topics, showing Marx's previously censored, politically uncomfortable views of Russia.

However, Ceaușescu was prepared to take a more decisive step in questioning Soviet policies. In the early years of his rule, he generally relaxed political pressures inside Romanian society,[33] which led to the late 1960s and early 1970s being the most liberal decade in Communist Romania. Gaining the public's confidence, Ceaușescu took a clear stand against the 1968 crushing of the Prague Spring by Leonid Brezhnev. After a visit from Charles de Gaulle earlier in the same year (during which the French President gave recognition to the incipient maverick), Ceaușescu's public speech in August deeply impressed the population, not only through its themes, but also because, uniquely, it was unscripted. He immediately attracted Western sympathies and backing, which lasted well beyond the 'liberal' phase of his regime; at the same time, the period brought forward the threat of armed Soviet invasion: significantly, many young men inside Romania joined the Patriotic Guards created on the spur of the moment, in order to meet the perceived threat.[34] President Richard Nixon was invited to Bucharest in 1969, which was the first visit of a United States president to a Communist country.

Alexander Dubček's version of Socialism with a human face was never suited to Romanian communist goals. Ceaușescu found himself briefly aligned with Dubček's Czechoslovakia and Josip Broz Tito's Yugoslavia. The latter friendship was to last well into the 1980s, with Ceaușescu adapting the Titoist doctrine of "independent socialist development" to suit his own objectives. Romania proclaimed itself a "Socialist" (in place of "People's") Republic to show that it was fulfilling Marxist goals without Moscow's overseeing.

The system's nationalist traits grew and progressively blended with Juche and Maoist ideals. In 1971, the Party, which had already been completely purged of internal opposition (with the possible exception of Gheorghe Gaston Marin),[32] approved the July Theses, expressing Ceaușescu's disdain of Western models as a whole, and the reevaluation of the recent liberalisation as bourgeois. The 1974 11th Congress tightened the grip on Romanian culture, guiding it towards Ceaușescu's nationalist principles:.[35] Notably, it demanded that Romanian historians refer to Dacians as having "an unorganised State", part of a political continuum that culminated in the Socialist Republic.[35] The regime continued its cultural dialogue with ancient forms, with Ceaușescu connecting his cult of personality to figures such as Mircea cel Bătrân (whom he styled Mircea the Great) and Mihai Viteazul. It also started adding Dacian or Roman versions to the names of cities and towns (Drobeta to Turnu Severin, Napoca to Cluj).[36]

A new generation of committed supporters on the outside confirmed the regime's character. Ceaușescu probably never emphasized that his policies constituted a paradigm for theorists of National Bolshevism such as Jean-François Thiriart, but there was a publicised connection between him and Iosif Constantin Drăgan, an Iron Guardist Romanian-Italian émigré millionaire (Drăgan was already committed to a Dacian Protochronism that largely echoed the official cultural policy).

Nicolae Ceaușescu had a major influence on modern-day Romanian populist rhetoric. In his final years, he had begun to rehabilitate the image of pro-Nazi dictator Ion Antonescu. Although Antonescu's was never a fully official myth in Ceaușescu's time, today's xenophobic politicians such as Corneliu Vadim Tudor have coupled the images of the two leaders into their versions of a national Pantheon. The conflict with Hungary over the treatment of the Magyar minority in Romania had several unusual aspects: not only was it a vitriolic argument between two officially Socialist states (as Hungary had not yet officially embarked on the course to a free market economy), it also marked the moment when Hungary, a state behind the Iron Curtain, appealed to the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe for sanctions to be taken against Romania. This meant that the later 1980s were marked by a pronounced anti-Hungarian discourse, which owed more to nationalist tradition than Marxism,[37] and the ultimate isolation of Romania on the World stage.

The strong opposition of his regime to all forms of perestroika and glasnost placed Ceaușescu at odds with Mikhail Gorbachev. He was very displeased when other Warsaw Pact countries decided to try their own versions of Gorbachev's reforms. In particular, he was incensed when Poland's leaders opted for a power-sharing arrangement with the Solidarity trade union. He even went as far as to call for a Warsaw Pact invasion of Poland—a significant reversal, considering how violently he opposed the invasion of Czechoslovakia 20 years earlier. For his part, Gorbachev made no secret of his distaste for Ceaușescu, whom he called "the Romanian führer."[4]

In November 1989, at the XIVth and last congress of the PCR, Ceaușescu condemned the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact and asked for the annulment of its consequences. In effect, this amounted to a demand for the return of Bessarabia (most of which was then a Soviet republic and since 1991 has been independent Moldova) and northern Bukovina, both of which had been occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940 and again at the end of World War II.

Selected published works

- Report during the joint solemn session of the CC of the Romanian Communist Party, the National Council of the Socialist Unity Front and the Grand National Assembly: Marking the 60th anniversary of the creation of a Unitary Romanian National State, 1978

- Major problems of our time: Eliminating underdevelopment, bridging gaps between states, building a new international economic order, 1980

- The solving of the national question in Romania (Socio-political thought of Romania's President), 1980

- Ceaușescu: Builder of Modern Romania and International Statesman, 1983

- The nation and co-habiting nationalities in the contemporary epoch (Philosophical thought of Romania's president), 1983

- Istoria poporului Român în concepția președintelui, 1988

Gallery

-

Ceauşescu's visit to Gheorgheni (1966)

-

Ceauşescu's visit to Sibiu (1967)

-

Ceauşescu and Josip Broz Tito at the Romanian-Yugoslav friendship meeting in Bucharest

-

Franz Jonas, the president of Austria, in visit in Bucharest, Romania (1969)

-

Jean-Bédel Bokassa with Nicolae Ceausescu during Bokassa's state visit to Romania (July 1970)

-

Ceauşescu and Kim Il-sung during the party and state visit to the DPR Korea (1971)

-

Fidel Castro visiting Ceauşescu in Romania (1972)

-

Yasser Arafat with Nicolae Ceauşescu during Arafat's visit to Bucharest (1974)

-

The Romanian presidential couple and Juan Perón and his wife in Buenos Aires in 1974

-

Ceauşescu with US President Jimmy Carter during a state visit to the USA (1978)

-

Ceauşescu with Doctor Rudolf Kirchschläger, president of Austria, during his visit to Romania (1978)

-

Addressing his New Year's Eve message on TV and radio (1978)

-

Ceauşescu's speech in Moscow in 1982 on the 60th anniversary of the Formation of the Soviet Union

-

Ceauşescu and Mikhail Gorbachev of the Soviet Union (1985)

Notes

- ^ Johanna Granville, "Dej-a-Vu: Early Roots of Romania's Independence," East European Quarterly, vol. XLII, no. 4 (Winter 2008), pp. 365-404.

- ^ Boyes, Roger (24 December 2009). "Ceausescu looked in my eyes and he knew that he was going to die". The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article6967099.ece.

- ^ a b c Ceausescu.org

- ^ a b c d e f g Sebetsyen, Victor (2009). Revolution 1989: The Fall of the Soviet Empire. New York City: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0375425322.

- ^ "Rumania: Enfant Terrible". Time. Monday, 2 April 1973. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,907041-1,00.html. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ Martin Sajdik, Michaël Schwarzinger (2008). European Union enlargement: background, developments, facts. New Jersey, USA: Transaction Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4128-0667-1.

- ^ David Phinnemore (2006). The EU and Romania: accession and beyond. London, UK,: Federal Trust for Education and Research. p. 13. ISBN 1-903403-79-0.

- ^ Roger Kirk, Mircea Răceanu. Romania versus the United States: diplomacy of the absurd, 1985–1989. Institute for the Study of Diplomacy, Georgetown University, 1994. p. 81. ISBN 0-312-12059-1.

- ^ Communist Romania's Demographic Policy, U.S. Library of Congress country study for details see Gail Kligman. 1998. The Politics of Duplicity. Controlling Reproduction in Ceausescu's Romania. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ^ Ceausescu's Longest-Lasting Legacy - the Cohort of '67

- ^ Karen Dente and Jamie Hess, Pediatric AIDS in Romania – A Country Faces Its Epidemic and Serves as a Model of Success, MedGenMed. 2006; 8(2): 11. Published online 2006 April 6.

- ^ See, for instance, Bohlen, Celestine, Measures to encourage reproduction included financial motivations for families who bear children, guaranteed maternity leave, and childcare support for mothers returning to work, work protection for women, and extensive access to medical control in all stages of pregnancy, as well as after. Medical control is seen as one of the most productive effects of the law, since all women who became pregnant were under the care of a qualified medical practitioner, even in rural areas. In some cases, if the women was unable to attend a medical office, the doctor would make visits to her home. "Upheaval in the East: Romania's AIDS Babies: A Legacy of Neglect," 8 February 1990, in The New York Times.

- ^ Aubin, Stephen P (1998). Distorting defense: network news and national security. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 158. ISBN 9780275963033. http://books.google.com/books?id=5YH5rPgWvzUC&pg=PA158&dq=revolution+romania+1989+death+toll&lr=&as_drrb_is=q&as_minm_is=0&as_miny_is=&as_maxm_is=0&as_maxy_is=&as_brr=3. Retrieved 28/June/2008.

- ^ Boyes, Roger (24 December 2009). "Ceausescu looked in my eyes and he knew that he was going to die". The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/europe/article6967099.ece. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ George Galloway and Bob Wylie, Downfall: The Ceausescus and the Romanian Revolution p. 198-199. Futura Publications, 1991

- ^ Daniel Simpson, "Ghosts of Christmas past still haunt Romanians"

- ^ The dictator and his henchman

- ^ Cdep.ro

- ^ a b Jurnalul Național, 25 January 2005

- ^ Yahoo! News

- ^ Nicolae Ceausescu's remains exhumed

- ^ Referl.org

- ^ Relations with the Communist World Library of Congress Country Study on Zaire (Former), Library of Congress Call Number DT644 .Z3425 1994. (TOC.) Data as of December 1993. Accessed online 15 October 2006.

- ^ List of honorary British Knights

- ^ Valenzuela, J. Samuel and Arturo Valenzuela (eds.), Military Rule in Chile: Dictatorship and Oppositions, p. 321

- ^ Romanian-Moldavian SSR relations, by Patrick Moore and the Romanian Section

- ^ The Official Website of the British Monarchy: "Queen and Honours", retrieved on 13 October 2010.

- ^ Official communique of the National Board of the Audio-Visual, originally at cna.org but now removed, accessible through web.archive.org

- ^ "Every Nation Received a Moon Rock, Some of them Can’t Find It" Houston Chronicle, Mike Tolson, 13 May 2010 (Reprint).

- ^ Mic Dicționar Enciclopedic

- ^ Geran Pilon, Chapter III, Communism with a Nationalist Face, p.60-66; Tănase, p.24

- ^ a b Geran Pilon, p.60

- ^ Tănase, p.23

- ^ Geran Pilon, p.62

- ^ a b Geran Pilon, p.61

- ^ Geran Pilon, p.61-63

- ^ Geran Pilon, p.63

References

- Mic Dicționar Enciclopedic ("Small encyclopedic dictionary"), 1978

- Edward Behr, Kiss the Hand you Cannot Bite, ISBN 0-679-40128-8

- Dumitru Burlan, Dupa 14 ani - Sosia lui Ceaușescu se destăinuie ("After 14 Years - The Double of Ceaușescu confesses"). Editura Ergorom. 31 July 2003 (in Romanian).

- Juliana Geran Pilon, The Bloody Flag. Post-Communist Nationalism in Eastern Europe. Spotlight on Romania, ISBN 1-56000-062-7; ISBN 1-56000-620-X

- Marian Oprea, "Au trecut 15 ani -- Conspirația Securității" ("After 15 years -- the conspiracy of Securitate"), in Lumea Magazin Nr 10, 2004: (in Romanian; link leads to table of contents, verifying that the article exists, but the article itself is not online).

- Viorel Patrichi, "Eu am fost sosia lui Nicolae Ceaușescu" ("I was Ceaușescu's double"), Lumea Magazin Nr 12, 2001 (in Romanian)

- Stevens W. Sowards, Twenty-Five Lectures on Modern Balkan History (The Balkans in the Age of Nationalism), 1996, in particular Lecture 24: The failure of Balkan Communism and the causes of the Revolutions of 1989

- Victor Stănculescu, "Nu vă fie milă, au 2 miliarde de lei în cont" ("Do not have mercy, they hold 2 billion lei [33 million dollars] in their account[s]"), in Jurnalul Național, 22 Nov 2004

- John Sweeney, The Life and Evil Times of Nicolae Ceaușescu, ISBN 0-09-174672-8

- Stelian Tănase, "Societatea civilă românească și violența" ("Romanian Civil Society and Violence"), in Agora, issue 3/IV, July–September 1991

- Filip Teodorescu, et al., Extracts from the minutes of a Romanian senate hearing, 14 December 1994, featuring the remarks of Filip Teodorescu.

External links

- Ceaușescu, Nicolae - Romania under Communism

- Communist Romania's Demographic Policy

- The Politicians and the revolution of 1989 (in Romanian)

- Gheorghe Brătescu, Clipa 638: Un complot ratat ("A failed scheme"). On how Milea died, probably killed by Stănculescu according to this writer, and the life of the Ceaușescu family. (In Romanian)

- Death of the Father: Nicolae Ceaușescu Focuses on his death, but also discusses other matters. Many photos.

- "Killer File" entry on Nicolae Andruța Ceaușescu Chronological overview of important events in his life and rule.

- Video on YouTube, Video of the trial and execution of Nicolae and Elena Ceaușescu.

Party political offices Preceded by

Gheorghe Gheorghiu-DejGeneral secretary of the Romanian Communist Party

1965–1989Succeeded by

Party dissolvedHeads of State of Romania United Principalities of Romania

Domnitor of Romania (1859–1881)Alexandru Ioan Cuza • Princely Lieutenancy (Lascăr Catargiu, Nicolae Golescu, Nicolae Haralambie) • Carol IKingdom of Romania

King of the Romanians (1881–1947)Carol I • Ferdinand • Michael I (with Prince Nicholas, Miron Cristea, Gheorghe Buzdugan replaced by Constantin Sărăţeanu as regents) • Carol II • Michael I (with Ion Antonescu as Conducător, 1940–1944)Communist Romania

President of the Presidium of the Republic (1947–1948)

President of the Presidium of the Grand National Assembly (1948–1961)

President of the State Council (1961–1974)

President of the S.R. Romania (1974–1989)Constantin Ion Parhon (with Ion Niculi, Mihail Sadoveanu, Gheorghe Stere, Ştefan Voitec, 1947–1948) • Petru Groza • Ion Gheorghe Maurer (with Mihail Sadoveanu and Anton Moisescu, 1958) Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej • Chivu Stoica (with Ion Gheorghe Maurer, Ştefan Voitec and Avram Bunaciu, 1965) • Chivu Stoica • Nicolae CeauşescuPost-1989 Romania

President of Romania (1989–present)*denotes interim • Categories: Heads of state of Romania, Presidents of Romania, Romanian monarchsFall of Communism Internal conditions Brezhnev stagnation · Cultural Revolution · Eastern Bloc · Eastern Bloc economies · Eastern Bloc politics · Eastern Bloc information dissemination · Eastern Bloc emigration and defection · KGB · Nomenklatura · Samizdat · Shortage economy · TotalitarianismInternational relations Active measures · Cold War · List of socialist countries · Predictions of Soviet collapse · Reagan Doctrine · Soviet Empire · Terrorism and the Soviet Union · Vatican oppositionReforms of socialism Events by country Eastern Bloc countries: Albania · Bulgaria · Czechoslovakia · East Germany · Hungary · Poland · Romania · Soviet Union · Yugoslavia

Former Soviet Republics: Armenia · Azerbaijan · Belarus · Estonia · Georgia · Latvia · Lithuania · Kazakhstan · Kirghistan · Moldova · Russia · Tajikstan · Turkmenistan · Ukraine · Uzbekistan

Other countries: Afghanistan · Angola · Benin · Burma · Cambodia · China · People's Republic of the Congo · Ethiopia · Mongolia · Mozambique · Nicaragua · Somalia · South YemenCommunist leaders Ramiz Alia · Heydar Aliyev · Yuri Andropov · Aung San · Siad Barre · Leonid Brezhnev · Fidel Castro · Nicolae Ceauşescu · Konstantin Chernenko · Mikhail Gorbachev · Károly Grósz · Hua Guofeng · Erich Honecker · Enver Hoxha · János Kádár · Nikita Khrushchev · Kim Il-sung · Milouš Jakeš · Wojciech Jaruzelski · Mathieu Kérékou · Mengistu Haile Mariam · Slobodan Milošević · Denis Sassou Nguesso · Saparmurat Niyazov · Daniel Ortega · Kaysone Phomvihane · Pol Pot · Tôn Đức Thắng · Phoumi Vongvichit · Ne Win · Deng Xiaoping · Todor ZhivkovAnti-communist leaders Corazon Aquino · Sali Berisha · Willy Brandt · Vladimir Bukovsky · Violeta Chamorro · Chiang Ching-kuo · Viacheslav Chornovil · Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj · Václav Havel · John F. Kennedy · Helmut Kohl · Vytautas Landsbergis · Pope John Paul II · Zianon Pazniak · Augusto Pinochet · Ronald Reagan · Lee Teng-hui · Margaret Thatcher · Harry S. Truman · Lech Wałęsa · Boris Yeltsin · Zhelyu ZhelevDemocracy movements Chinese democracy movement · Civic Forum · Democratic Party of Albania · Democratic Russia · Sąjūdis · Rukh · Solidarity · Popular Front of Latvia · Popular Front of Estonia · Public Against Violence · Belarusian Popular Front · National League for Democracy · National Opposition Union · United Nationalist Democratic Organization · National Salvation Front · Union of Democratic ForcesEvents People Power Revolution · Revolutions of 1989 · April 9 tragedy · Black January · Baltic Way · 1988 Polish strikes · Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 · Removal of Hungary's border fence · Polish Round Table Talks · Hungarian Round Table Talks · Pan-European Picnic · Monday demonstrations in East Germany · Fall of the Berlin Wall · Malta Summit · German reunification · January 1991 events in Lithuania · January 1991 events in Latvia · 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt · Yemeni unification · Chilean transition to democracyPost-collapse Colour revolution · Decommunization · Democratization · Economic liberalization · Economic reforms after the collapse of socialism · Neo-Stalinism · North Korean famine · Oslo Accords · Post-communism · Putinism · Special Period · Yugoslav Wars1940s Yalta Conference · Operation Unthinkable · Potsdam Conference · Gouzenko Affair · War in Vietnam (1945–1946) · Iran crisis of 1946 · Greek Civil War · Corfu Channel Incident · Restatement of Policy on Germany · First Indochina War · Truman Doctrine · Asian Relations Conference · Marshall Plan · Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948 · Tito–Stalin split · Berlin Blockade · Western betrayal · Iron Curtain · Eastern Bloc · Chinese Civil War (Second round)1950s Korean War · 1953 Iranian coup d'état · Uprising of 1953 in East Germany · 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état · Partition of Vietnam · First Taiwan Strait Crisis · Geneva Summit (1955) · Poznań 1956 protests · Hungarian Revolution of 1956 · Suez Crisis · Sputnik crisis · Second Taiwan Strait Crisis · Cuban Revolution · Kitchen Debate · Asian–African Conference · Bricker Amendment · McCarthyism · Operation Gladio · Hallstein Doctrine1960s Congo Crisis · Sino–Soviet split · 1960 U-2 incident · Bay of Pigs Invasion · Berlin Wall · Cuban Missile Crisis · Vietnam War · 1964 Brazilian coup d'état · United States occupation of the Dominican Republic (1965–1966) · South African Border War · Rhodesian Bush War · Transition to the New Order · Domino theory · ASEAN Declaration · Laotian Civil War · Greek military junta of 1967–1974 · Six-Day War · War of Attrition · Cultural Revolution · Sino-Indian War · Prague Spring · Goulash Communism · Sino–Soviet border conflict1970s Détente · Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty · Black September in Jordan · Cambodian Civil War · Realpolitik · Ping Pong Diplomacy · Four Power Agreement on Berlin · 1972 Nixon visit to China · 1973 Chilean coup d'état · Yom Kippur War · Strategic Arms Limitation Talks · Angolan Civil War · Mozambican Civil War · Ogaden War · Sino-Albanian split · Cambodian–Vietnamese War · Sino-Vietnamese War · Iranian Revolution · Operation Condor · Bangladesh Liberation War · Korean Air Lines Flight 9021980s Soviet war in Afghanistan · 1980 and 1984 Summer Olympics boycotts · Solidarity (Soviet reaction) · Contras · Central American crisis · RYAN · Korean Air Lines Flight 007 · Able Archer 83 · Star Wars · Invasion of Grenada · People Power Revolution · Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 · United States invasion of Panama · Fall of the Berlin Wall · Revolutions of 1989 · Glasnost · Perestroika1990s Foreign

policyIdeologies Capitalism (Chicago school · Keynesianism · Monetarism · Neoclassical economics · Supply-side economics · Thatcherism · Reaganomics) · Communism (Marxism–Leninism · Castroism · Eurocommunism · Guevarism · Juche · Left communism · Maoism · Stalinism · Titoism · Trotskyism) · Liberal democracy · Social democracyOrganizations Propaganda Races See also Brinkmanship · NATO–Russia relations · Soviet and Russian espionage in U.S. · Soviet Union – United States relations · US–Soviet summitsCategories:- 1918 births

- 1989 deaths

- Annulled Honorary Knights Grand Cross of the Order of the Bath

- Anti-fascists

- Cold War leaders

- Communist rulers

- Deaths by firearm in Romania

- Executed presidents

- Executed Romanian people

- Filmed executions

- General Secretaries of the Romanian Communist Party

- Inmates of Târgu Jiu camp

- Grand Crosses Special Class of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Légion d'honneur recipients

- Knights of the Elephant

- Members of the Great National Assembly

- Members of the Chamber of Deputies of Romania

- Order of St. Olav

- People executed by firing squad

- People executed by Romania

- People of the Romanian Revolution of 1989

- People from Olt County

- Presidents of Romania

- Recipients of the Order of Karl Marx

- Recipients of the Order of the October Revolution

- Romanian atheists

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.