- Common Kestrel

-

Common Kestrel

Adult male Falco tinnunculus tinnunculus Conservation status Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Aves Subclass: Neornithes Infraclass: Neognathae Superorder: Neoaves Order: Falconiformes Family: Falconidae Genus: Falco Species: F. tinnunculus Binomial name Falco tinnunculus

Linnaeus, 1758Subspecies About 11, see text

Western part of range of F. t. tinnunculus

(also occurs in Siberia farther east)

Yellow = breeding only, green = all-yearSynonyms Falco rupicolus Daudin, 1800 (but see text)

Falco tinnunculus interstictus (lapsus)The Common Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus) is a bird of prey species belonging to the kestrel group of the falcon family Falconidae. It is also known as the European Kestrel, Eurasian Kestrel, or Old World Kestrel. In Britain, where no other brown falcon occurs, it is generally just called "the kestrel".[1]

This species occurs over a large range. It is widespread in Europe, Asia, and Africa, as well as occasionally reaching the east coast of North America[citation needed]. But although it has colonized a few oceanic islands, vagrant individuals are generally rare; in the whole of Micronesia for example, the species was only recorded twice each on Guam and Saipan in the Marianas.[2]

Contents

Description

Common Kestrels measure 32–39 cm (13–15 in) from head to tail, with a wingspan of 65–82 cm (26–32 in). Females are noticeably larger, with the adult male weighing 136-252 g (c,5-9 oz), around 155 g (around 5.5 oz) on average; the adult female weighs 154-314 g (about 5.5-11 oz), around 184 g (around 6.5 oz) on average. They are thus small compared with other birds of prey, but larger than most songbirds. Like the other Falco species, they have long wings as well as a distinctive long tail.[3]

Their plumage is mainly light chestnut brown with blackish spots on the upperside and buff with narrow blackish streaks on the underside; the remiges are also blackish. Unlike most raptors, they display sexual colour dimorphism with the male having less black spots and streaks, as well as a blue-grey cap and tail. The tail is brown with black bars in females, and has a black tip with a narrow white rim in both sexes. All Common Kestrels have a prominent black malar stripe like their closest relatives.[3]

The cere feet, and a narrow ring around the eye are bright yellow; the toenails, bill and iris are dark. Juveniles look like adult females, but the underside streaks are wider; the yellow of their bare parts is paler. Hatchlings are covered in white down feathers, changing to a buff-grey second down coat before they grow their first true plumage.[3]

Behaviour and ecology

In the cool-temperate parts of its range, the Common Kestrel migrates south in winter; otherwise it is sedentary, though juveniles may wander around in search for a good place to settle down as they become mature. It is a diurnal animal of the lowlands and prefers open habitat such as fields, heaths, shrubland and marshland. It does not require woodland to be present as long as there are alternate perching and nesting sites like rocks or buildings. It will thrive in treeless steppe where there are abundant herbaceous plants and shrubs to support a population of prey animals. The Common Kestrel readily adapts to human settlement, as long as sufficient swathes of vegetation are available, and may even be found in wetlands, moorlands and arid savanna. It is found from the sea to the lower mountain ranges, reaching up to 4,500 m (15,000 ft) ASL in the hottest tropical parts of its range but only to about 1,750 meters (5,700 ft) in the subtropical climate of the Himalayan foothills[4]

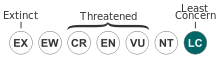

Globally, this species is not considered threatened by the IUCN.[5] Its stocks were affected by the indiscriminate use of organochlorines and other pesticides in the mid-20th century, but being something of an r-strategist able to multiply quickly under good conditions it was less affected than other birds of prey. The global population is fluctuating considerably over the years but remains generally stable; it is roughly estimated at 1-2 million pairs or so, about 20% of which are found in Europe. There has been a recent decline in parts of Western Europe such as Ireland. Subspecies dacotiae is quite rare, numbering less than 1000 adult birds in 1990, when the ancient western Canarian subspecies canariensis numbered about ten times as many birds.[3]

Food and feeding

When hunting, the Common Kestrel characteristically hovers about 10–20 m (c.30–70 ft) above the ground, searching for prey, either by flying into the wind or by soaring using ridge lift. Like most birds of prey, Common Kestrels have keen eyesight enabling them to spot small prey from a distance. Once prey is sighted, the bird makes a short, steep dive toward the target. It can often be found hunting along the sides of roads and motorways. This species is able to see near ultraviolet light, allowing the birds to detect the urine trails around rodent burrows as they shine in an ultraviolet colour in the sunlight.[6] Another favourite (but less conspicuous) hunting technique is to perch a bit above the ground cover, surveying the area. When the birds spot prey animals moving by, they will pounce on them. They also prowl a patch of hunting ground in a ground-hugging flight, ambushing prey as they happen across it.[3]

Common Kestrels eat almost exclusively mouse-sized mammals: typically voles, but also shrews and true mice supply up to three-quarters or more of the biomass most individuals ingest. On oceanic islands (where mammals are often scarce), small birds – mainly passerine – may make up the bulk of its diet[7] while elsewhere birds are only important food during a few weeks each summer when unexperienced fledglings abound. Other suitably sized vertebrates like bats, frogs[citation needed] and lizards are eaten only on rare occasions. However, kestrels may more often prey on lizards at southern latitudes, in northern latitudes the kestrel is found to more often deliver lizards to their nestlings during midday and also with increasing ambient temperature [8]. Seasonally, arthropods may be a main prey item. Generally, invertebrates like camel spiders and even earthworms, but mainly sizeable insects such as beetles, orthopterans and winged termites are eaten with delight whenever the birds happen across them.[3]

F. tinnunculus requires the equivalent of 4-8 voles a day, depending on energy expenditure (time of the year, amount of hovering, etc.). They have been known to catch several voles in succession and cache some for later consumption. A individual nestling consume on average 4.2 g/h, this is equivalent to 67.8 g/d (3-4 voles per day) [9].

Reproduction

The Common Kestrel starts breeding in spring (or the start of the dry season in the tropics), i.e. April/May in temperate Eurasia and some time between August and December in the tropics and southern Africa. It is a cavity nester, preferring holes in cliffs, trees or buildings; in built-up areas, Common Kestrels will often nest on buildings, and generally they often reuse the old nests of corvids if are available. The diminutive subspecies dacotiae, the sarnicolo of the eastern Canary Islands is peculiar for nesting occasionally in the dried fronds below the top of palm trees, apparently coexisting rather peacefully with small songbirds which also make their home there.[10] In general, Common Kestrels will usually tolerate conspecifics nesting nearby, and sometimes a few dozen pairs may be found nesting in a loose colony.[3]

The clutch is normally 3-6 eggs, but may contain any number of eggs up to seven; even more eggs may be laid in total when some are removed during the laying time, which lasts about 2 days per egg laid. The eggs are abundantly patterned with brown spots, from a wash that tinges the entire surface buffish white to large almost-black blotches. Incubation lasts some 4 weeks to one month, and only the female hatches the eggs. The male is responsible for provisioning her with food, and for some time after hatching this remains the same. Later, both parents share brooding and hunting duties until the young fledge, after 4–5 weeks. The family stays close together for a few weeks, up to a month or so, during which time the young learn how to fend for themselves and hunt prey. The young become sexually mature the next breeding season.[3]

Data from Britain shows nesting pairs bringing up about 2-3 chicks on average, though this includes is a considerable rate of total brood failures; actually, few pairs that do manage to fledge offspring raise less than 3 or 4. Population cycles of prey, particularly voles, have a considerable influence on breeding success. Most Common Kestrels die before they reach 2 years of age; mortality til the first birthday may be as high as 70%. At least females generally breed at one year of age;[11] possibly, some males take a year longer to maturity as they do in related species. The biological lifespan to death from senescence can be 16 years or more, however; one was recorded to have lived almost 24 years.[11]

Evolution and systematics

This species is part of a clade that contains the kestrel species with black malar stripes, a feature which apparently was not present in the most ancestral kestrels. They seem to have radiated in the Gelasian (Late Pliocene,[12] roughly 2.5-2 mya, probably starting in tropical East Africa, as indicated by mtDNA cytochrome b sequence data analysis and considerations of biogeography. The Common Kestrel's closest living relative is apparently the Nankeen or Australian Kestrel (F. cenchroides), which probably derived from ancestral Common Kestrels settling in Australia and adapting to local conditions less than one million years ago, during the Middle Pleistocene.[13]

The Rock Kestrel may be a distinct species F. rupicolus, more distantly related to the Common Kestrel proper than the Nankeen Kestrel; its relationship to the other African and South Asian kestrel taxa remains insufficiently studied. The Canary Islands subspecies are apparently independently derived from Continental birds.[14]

The Lesser Kestrel (F. naumanni), which much resembles a small Common Kestrel with no black on the upperside except wing and tail tips, is probably not very closely related to the present species, and the American Kestrel (F. sparverius) is apparently not a true kestrel at all.[14] Both species have much grey in their wings in males, which does not occur in the Common Kestrel or its close living relatives but does in almost all other falcons.

Subspecies

A number of subspecies of the Common Kestrel are known, though some are hardly distinct and may be invalid. Most of them differ little, and mainly in accordance with Bergmann's and Gloger's Rules. Tropical African forms have less grey in the male plumage.[3]

- Falco tinnunculus tinnunculus Linnaeus, 1758

- Temperate areas of Europe, North Africa, the Middle East, and Asia north of the Hindu Kush-Himalaya mountain ranges to the NW Sea of Okhotsk region. Northern Asian populations migrate south in winter, apparently not crossing the Himalayas but diverting to the west.

- Falco (tinnunculus) rupicolus Daudin, 1800 – Rock Kestrel

- NW Angola and S Zaire to S Tanzania, and south to South Africa. Probably a distinct species, but its limits with rufescens require further study. It differs markedly from the other subspecies of the F. tinnunculus complex. In particular, the females have what in other subspecies are typically male characteristics such as a grey head and tail, and spotted rather than barred upperparts. The Rock Kestrel has less heavily marked, brighter chestnut upperparts and its underparts are also a bright chestnut that contrasts with the nearly unmarked white underwings. Females tend to have more black bands in the central tail feathers than males. The open mountain habitat also differs from that its relatives.

- Falco tinnunculus rufescens Swainson, 1837

- Sahel east to Ethiopia, southwards around Congo basin to S Tanzania and NE Angola.

- Falco tinnunculus interstictus McClelland, 1840

- Breeds East Asia from Tibet to Korea and Japan, south into Indochina. Winters to the south of its breeding range, from India to the Philippines (where it is localized, e.g. from Mindanao only two records exist[15]). Birds in the Himalayan foothills (e.g. of Bhutan[16]) might be all-year residents

- Falco tinnunculus rupicolaeformis (C. L. Brehm, 1855)

- Arabian Peninsula except in the desert and across the Red Sea into Africa.

- Falco tinnunculus neglectus Schlegel, 1873

- Northern Cape Verde Islands.

- Falco tinnunculus canariensis (Koenig, 1890)

- Madeira and western Canary Islands. The more ancient Canaries subspecies.

- Falco tinnunculus dacotiae Hartert, 1913 – Local name: sarnicolo

- Eastern Canary Islands: Fuerteventura, Lanzarote, Chinijo Archipelago. A more recently evolved subspecies than canariensis.

- Falco tinnunculus objurgatus (Baker, 1929)

- Western, Nilgiris and Eastern Ghats of India; Sri Lanka. Heavily marked, has rufous thighs with dark grey head in males.[17]

- Falco tinnunculus archerii (Hartert & Neumann, 1932)

- Falco tinnunculus alexandri Bourne, 1955

- Southwestern Cape Verde Islands.

The Common Kestrels of Europe living during cold periods of the Quaternary glaciation differed slightly in size from the current population; they are sometimes referred to as paleosubspecies F. t. atavus (see also Bergmann's Rule). The remains of these birds, which presumably were the direct ancestors of the living F. t. tinnunculus (and perhaps other subspecies), are found throughout the then-unglaciated parts of Europe, from the Late Pliocene (ELMA Villanyian/ICS Piacenzian, MN16) about 3 million years ago to the Middle Pleistocene Saalian glaciation which ended about 130.000 years ago, when they finally gave way to birds indistinguishable from those living today. Some of the voles the Ice Age Common Kestrels ate – such as European Pine Voles (Microtus subterraneus) – were indistinguishable from those alive today. Other prey species of that time evolved more rapidly (like M. malei, the presumed ancestor of today's Tundra Vole M. oeconomus), while yet again others seem to have gone entirely extinct without leaving any living descendants – for example Pliomys lenki, which apparently fell victim to the Weichselian glaciation about 100.000 years ago.[18]

In culture

The Kestrel is sometimes seen, like other birds of prey, as a symbol of the power and vitality of nature. In "Into Battle" (1915), the war poet Julian Grenfell invokes the superhuman characteristics of the Kestrel among several birds, when hoping for prowess in battle:

"The kestrel hovering by day,

And the little owl that call at night,

Bid him be swift and keen as they,

As keen of ear, as swift of sight."Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844–1889) writes on the kestrel in his poem The Windhover, exalting in their mastery of flight and their majesty in the sky.

"I caught this morning morning's minion, king-

dom of daylight's dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding"Archaic names for the kestrel include windhover and windfucker, due to its habit of beating the wind (hovering in air).[19]

A kestrel is also one of the main characters in The Animals of Farthing Wood.

Footnotes

- ^ MWBG [2009]

- ^ Orta (1994), Wiles et al. (2000, 2004)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Orta (1994)

- ^ Orta (1994), Inskipp et al. (2000)

- ^ BLI (2008)

- ^ Viitala et al. (1995)

- ^ Wiles et al. (2004)

- ^ Steen et al. (2011a)

- ^ Steen et al. (2011b)

- ^ Álamo Távio (1975)

- ^ a b AnAge [2010]

- ^ Possibly to be reclassified as Early Pleistocene.

- ^ See Groombridge et al. (2002) for a thorough discussion of Common Kestrel and relatives' divergence times.

- ^ a b Groombridge et al. (2002)

- ^ Peterson et al. (2008)

- ^ Inskipp et al. (2000)

- ^ Whistler (1949): 385-387, Rasmussen & Anderton (2005): 112-113

- ^ Mlíkovský (2002): pp.222-223, Mourer-Chauviré et al. (2003)

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

References

- Álamo Tavío, Manuel (1975): Aves de Fuerteventura en peligro de extinción ["Birds of Fuerteventura threatened with extinction"]. In: Asociación Canaria para Defensa de la Naturaleza (ed.): Aves y plantas de Fuerteventura en peligro de extinción: 10-32 [in Spanish]. Las Palmas de Gran Canaria. PDF fulltext

- AnAge [2010]: Falco tinnunculus life history data. Retrieved 2010-AUG-01.

- BirdLife International (BLI) (2008). Falco tinnunculus. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 2 January 2009.

- Groombridge, Jim J.; Jones, Carl G.; Bayes, Michelle K.; van Zyl, Anthony J.; Carrillo, José; Nichols, Richard A. & Bruford, Michael W. (2002): A molecular phylogeny of African kestrels with reference to divergence across the Indian Ocean. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 25(2): 267–277. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00254-3 PDF fulltext

- Inskipp, Carol; Inskipp, Tim & Sherub (2000): The ornithological importance of Thrumshingla National Park, Bhutan. Forktail 14: 147-162. PDF fulltext* Mangoverde World Bird Guide (MWBG) [2009]: Eurasian Kestrel Falco tinnunculus. Retrieved 2009-JAN-02.

- Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002): Cenozoic Birds of the World (Part 1: Europe). Ninox Press, Prague. ISBN 80-901105-3-8 PDF fulltext

- Mourer-Chauviré, C.; Philippe, M.; Quinif, Y.; Chaline, J.; Debard, E.; Guérin, C. & Hugueney, M. (2003): Position of the palaeontological site Aven I des Abîmes de La Fage, at Noailles (Corrèze, France), in the European Pleistocene chronology. Boreas 32: 521–531. doi:10.1080/03009480310003405 (HTML abstract)

- Orta, Jaume (1994): 26. Common Kestrel. In: del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew & Sargatal, Jordi (editors): Handbook of Birds of the World, Volume 2 (New World vultures to Guineafowl): 259-260, plates 26. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. ISBN 84-87334-15-6

- Peterson, A. Townsend; Brooks, Thomas; Gamauf, Anita; Gonzalez, Juan Carlos T.; Mallari, Neil Aldrin D.; Dutson, Guy; Bush, Sarah E. & Fernandez, Renato (2008): The Avifauna of Mt. Kitanglad, Bukidnon Province, Mindanao, Philippines. Fieldiana Zool. New Series 114: 1-43. DOI:10.3158/0015-0754(2008)114[1:TAOMKB]2.0.CO;2 PDF fulltext

- Rasmussen, Pamela C. & Anderton, John T. (2005): Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide (Vol. 2). Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions.

- Steen, R., Løw, L.M. & Sonerud, T. 2011a. Delivery of Common Lizards (Zootoca (Lacerta) vivipara) to nests of Eurasian Kestrels (Falco tinnunculus) determined by solar height and ambient temperature. - Canadian Journal of Zoology. 89: 199-205. HTML abstract

- Steen, R., Løw, L.M., Sonerud, G.A., Selås, V. & Slagsvold, T. 2011b. Prey delivery rates as estimates of prey consumption by Eurasian Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus). - Ardea. 99: 1-8. PDF fulltext

- Viitala, Jussi; Korpimäki, Erkki; Palokangas, Päivi & Koivula, Minna: Attraction of kestrels to vole scent marks visible in ultraviolet light. Nature 373(6513): 425 - 427 doi:10.1038/373425a0 (HTML abstract)

- Whistler, Hugh (1949): Popular handbook of Indian birds (4th ed.). Gurney and Jackson, London. Fulltext at Internet Archive

- Wiles, Gary J.; Worthington, David J.; Beck, Robert E. Jr.; Pratt, H. Douglas; Aguon, Celestino F. & Pyle, Robert L. (2000): Noteworthy Bird Records for Micronesia, with a Summary of Raptor Sightings in the Mariana Islands, 1988-1999. Micronesica 32(2): 257-284. PDF fulltext

- Wiles, Gary J.; Johnson, Nathan C.; de Cruz, Justine B.; Dutson, Guy; Camacho, Vicente A.; Kepler, Angela Kay; Vice, Daniel S.; Garrett, Kimball L.; Kessler, Curt C. & Pratt, H. Douglas (2004): New and Noteworthy Bird Records for Micronesia, 1986–2003. Micronesica 37(1): 69-96. HTML abstract

External links

- ARKive - images and movies of the kestrel (Falco tinnunculus)

- Kestrels in Israel

- Royal Society for the Protection of Birds

- Text of the Hopkins poem

- Kestrel on-line 2011: Brest, Belarus

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.