- Charles Barry

-

For his son, also an architect, see Charles Barry, Jr.. For the Irish lawyer, see Charles Robert Barry.

Sir Charles Barry

Born 23 May 1795

Bridge Street, Westminster, LondonDied 12 May 1860

LondonNationality English Awards Royal Gold Medal (1850) Work Buildings Palace of Westminster Sir Charles Barry FRS (23 May 1795 – 12 May 1860) was an English architect, best known for his role in the rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster (also known as the Houses of Parliament) in London during the mid-19th century, but also responsible for numerous other buildings and gardens.

Contents

Background and training

Born on 23 May 1795[1] in Bridge Street, Westminster (opposite the future site of the Clock Tower of the Palace of Westminster), he was the fourth son of Walter Edward Barry (died 1805) a stationer,[1] and Frances Barry née Maybank (died 1798). He was baptised at St Margaret's, Westminster. His father remarried shortly after Frances died and Barry's stepmother Sarah would bring him up.[1] He was educated at private schools in Homerton and then Aspley Guise,[2] before being apprenticed to Middleton & Bailey,[3] Lambeth architects & surveyors, at the age of 15. Annually from 1812 to 1815 Barry exhibited Drawings at the Royal Academy.[4] Upon the death of his father, Barry had inherited a sum of money that allowed him, after Coming of age to under take a Grand Tour, extensively around the Mediterranean and Middle East from 28 June 1817 to August 1820.[5]

He visited France, while in Paris he spent several days at the Musée du Louvre[6]; Italy, in Rome he sketched, antiquities sculptures and paintings at the Vatican Museums and other galleries,[7] then on to Naples and Pompeii, Bari then to Corfu; while in Italy Barry had met Charles Lock Eastlake, an architect Mr Kinnaird and a Mr Johnson (later a professor at Haileybury and Imperial Service College)[8] with these gentlemen he visited Greece, where their itinerary covered Athens which they left on 25 June 1818, Mount Parnassus, Delphi, Aegina, then the Cyclades, including Delos to Smyrna[9] and Turkey where Barry greatly admired the magnificence of Hagia Sophia,[10] from Constantinople he visited the Troad, Assos, Pergamon and back to Smyrna.[11] Whilst in Athens, Barry met a Mr. David Baillie, who was taken with Barry's sketches and offered to pay him £200 a year plus any expenses to accompany him to Egypt, Palestine and Syria in return for Barry's drawings of the countries they visited.[1] The major sites of the middle east that were visted included in Egypt, Dendera,[12] Temple of Edfu,[13] Philae[14] (it was here that he met his future client William John Bankes on 13 January 1819[15]), then returning back up the Nile to Thebes, Luxor and Karnak[16] then back to Cairo and Giza with its pyramids.[16] Continuing on through the middle east the major sites and cities visted were: Jaffa, the Dead Sea, Jerusalem including the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, Bethlehem,[16] Baalbek, Jerash, Beirut. Damascus and Palmyra,[17] then on to Homs,[18] on 18 June 1819 Barry parted from Mr Baillie at Tripoli, Lebanon, Barry having drawn over 500 sketches.[19] Barry then travelled on to Cyprus, then Rhodes, Halicarnassus, Ephesus, Smyrna from where he sailed on 16 August 1819 for Malta.[20]

Barry then sailed from Malta to Syracuse, Sicily,[21] then Italy and back through France. His travels in Italy exposed him to Renaissance architecture and arriving in Rome in January 1820, it was here on 24 February that he met an architect, John Lewis Wolfe[22] (their friendship continued until Barry died), who inspired him to become an architect. The building that inspired Barry's admiration for Italian architecture was the Palazzo Farnese.[23] He and Mr Wolfe then over the following months studied the architecture of Florence where the Palazzo Strozzi greatly impressed him, Vicenza, Venice and Verona together.[1]

Early career

While in Rome he had met Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, through whom he met Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland and his wife Elizabeth Fox, Baroness Holland, their London home, Holland House[24] was the centre of the Whig Party, Barry was invited to the gatherings at the house, and there met many of the prominent members of the group; this led to many of his subsequent commissions. Barry set up his home and office in Ely Place in 1821,[3] in 1827 he moved to 27 Foley Place,[25] then in 1842 he moved to 32, Great George Street[26] and finally to The Elms, Clapham Common.[27]

He began designing churches for the Commissioners, and he found out that they preferred designs in Gothic and Greek styles, so he put efforts into building those kinds of churches. His first buildings were in Gothic Revival architecture style, including two in Lancashire, St. Matthew, Campfield, Manchester (1821–22) and All Saints' Church, Whitefield (or Stand) (1822–25).[28] Barry designed three churches for the Commissioners in Islington, all were built during (1826–1828), these were, Holy Trinity,[29] St. John's[30] and St. Paul's,[31] and all are Gothic in style.

Holy Trinity Church, Hurstpierpoint

Holy Trinity Church, Hurstpierpoint

Two further Gothic churches in Lancashire, not for the Commissioners followed in 1824: Ringley Church, partially rebuilt in 1851-54 and Barry's neglected Welsh Baptist Chapel, on Upper Brook Street (1837–39)[32] in Manchester (and owned by the City Council), is currently open to the elements and at serious risk after its roof was removed in late 2005. One of the first works by which his abilities became generally known was the Gothic St Peter's Church, Brighton (1824–28). His church designs also include one in Hove, East Sussex St Andrew's[33] in Waterloo Street, Brunswick, (1827–28); the plan of the building is in line with Georgian architecture, though stylistically the Italianate style was used, the only classical church Barry designed. The Gothic Hurstpierpoint church[34] (1843–45), with its tower and spire, unlike his earlier churches this was much closer to the Cambridge Camden Society's approach to church design. According to the his son Alfred,[35] Barry later disowned these early church designs of the 1820s and wished he could destroy them.

His first major civil commission came when he won a competition to design the new Royal Manchester Institution[36] (1824–35) for the promotion of Literature, Science & Arts (now part of the Manchester Art Gallery), in Greek revival style, the only public building by Barry in that style. Also in north-west England, he designed Buile Hill House[37] (1825) in Salford this is the only known house where Barry used Greek revival architecture. The Royal Sussex County Hospital[38] was erected to Barry's design (1828) in a very plain classical style.

Thomas Attree's villa,[39] the only one to built of a series of villa's designed for the area by Barry and the Pepper Pot, whose original function was a water tower, Queen's Park, Brighton (1830). The marked preference for Italian architecture, which he acquired during his travels showed itself in various important undertakings of his earlier years, the first significant example being the Travellers Club,[40] in Pall Mall, built in 1832, as with all his urban commissions in this style the design was astylar. He designed the Gothic King Edward's School,[41] New Street, Birmingham (1833–37), demolished 1936.

His last work in Manchester was the Italianate Manchester Athenaeum (1837–39),[42] this is now part of Manchester Art Gallery. From (1835–37) he rebuilt Royal College of Surgeons of England,[43] in Lincoln's Inn Fields, Westminster, he preserved the Ionic portico from the earlier building (1806–13) designed by George Dance the Younger, the building has been further extended (1887–88) and (1937). In 1837 he won the competition to design the Reform Club,[44] Pall Mall, London, this is one of his finest Italianate public buildings, notable for its double height central saloon with glazed roof, his favourite building in Rome, the Farnese Palace influenced the design.

Country house work

A major focus of his career was the remodelling of older country houses, his first major commission was the transformation of Henry Holland's Trentham Hall,[45] Staffordshire (1834–40) it was remodelled in the Italianate style with a large tower (a feature Barry often included in his country houses), Barry also designed the Italianate gardens,[46] with parterres and fountains, largely demolished in 1912, only a small portion of the house consisting of the porte-cochère, with a curving corridor and the stables are still standing, although the gardens are undergoing a restoration, additionally the belvedere from the top of the tower survives as a folly at Sandon Hall.[47]

At Bowood House,[48] Wiltshire, (1834–38), for Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne he added the tower, made alterations to the gardens and designed the Italianate entrance lodge, also for the same client he designed the Lansdowne Monument[49] (1845). Walton house[50] followed in (1835–39), Walton-on-Thames, again he used an Italianate style with a three storey tower over the entrance porte-cochère demolished 1973. Then in (1835–38) he remodeled Sir Roger Pratt's Kingston Lacy, the interiors being his work, as well as the exterior being re-clad in stone.

Highclere Castle,[51] Hampshire, (c.1842-50) with its large tower was remodeled in Elizabethan style for the Henry Herbert, 3rd Earl of Carnarvon, externally the building was completely altered, the plain Georgian building virtually rebuilt, although little of the interior is by Barry, his patron dying in 1849, and Thomas Allom completed it in 1861. At Duncombe Park[52] Yorkshire, he designed new wings added (1843–46), these were in the English Baroque style of the main block. At Harewood House[53] he remodeled (1843–50) the John Carr exterior adding an extra floor to the end pavilions and replacing the portico on the south front with Corinthian pilasters, some of the Robert Adam interiors were remodeled, the dining room being entirely by Barry, and created the formal terraces and parterres surrounding the house.

He remodeled Dunrobin Castle,[54] Sutherland, Scotland (1844–48) in Scots Baronial Style for George Sutherland-Leveson-Gower, 2nd Duke of Sutherland for whom he had remodeled Trentham Hall, due to a fire in the early 20th century little of Barry's interiors survive at Dunrobin, the gardens with their fountains and parterres are also by Barry. Canford Manor,[55] Dorset,was extended in a Tudor Gothic style (1848–52), including a large entrance tower, the most unusual interior is the Nineveh porch, built to house Assyrian sculptures from the eponymous palace, this has an interior decorated with Assyrian motifs.

James Paine's Shrubland Park[56] was remodeled in (1849–54) with its Italianate tower, entrance porch, the lower hall with Corinthian columns and glass domes and the impressive formal gardens based on Italian Renaissance gardens, including a 70 foot high series of terraces linked by a grand flight of steps linking terraces, with an open temple structure at the top, originally there were cascades of water either side of the staircase, the main terrace is at the center of a string of gardens nearly a mile in length.[57] He remodeled Gawthorpe Hall[58] an Elizabethan house situated south-east of the small town of Padiham, in the borough of Burnley, Lancashire, England, originally a pele tower, built in the 14th century as a defense against the invading Scots. Around 1600 a Jacobean mansion was dovetailed around the pele but today's hall is re-design of the house, using the original Elizabethan style (1850–52).

His last major remodeling work was Cliveden[59] again for the 2nd Duke of Sutherland, here he built a new central block after the previous building was burnt down (1850–51), rising to three floors in the Italianate Style, the lowest floor had arch headed windows, the upper two floors have giant Ionic pilasters, he also designed the parterre's below the house,[60] little of Barry's interiors survived later remodeling.

Later urban work

Barry remodelled Trafalgar Square[61] (1840–45) he designed the north terrace with the steps at either end, and the sloping walls on the east and west of the square, the two fountain basins are also to Barry's design, although Edwin Lutyens re-designed the actual fountains (1939).[61]

The (Old) Treasury (Now Cabinet Office) Whitehall by John Soane, built (1824-6) was virtually rebuilt[61] by Barry (1844–47). It consists of 23 bays with a giant Corinthian order over a rusticated ground floor, the five bays at each end project slightly from the facade.

Bridgewater House, Westminster,[62] London (1845–64) for Francis Egerton, 1st Earl of Ellesmere, in a grand Italianate style. The structure was complete by 1848, but interior decoration was only finished by 1864. The main (south) front is 144 feet long, of nine bays in more massive version of his earlier Reform Club, the garden (west) front is of seven bays. The interiors are intact apart from the north wing which was bombed in The Blitz. The main interior is the central Saloon, a roofed courtyard of two storeys, of three by five bays of arches on each floor, the walls are lined with scagliola, the coved ceiling is glazed and the centre has three glazed saucer domes. The decoration of the major rooms is not the work of Barry.

The last major commission of Barry's was Halifax Town Hall[63] (1859–62), in a North Italian Cinquecento style, and a grand tower with spire, the interior includes a central hall similar to that at Bridgewater House, the building was completed after Barry's death by his son Edward Middleton Barry.

Completed after Barry's death in 1863 was the classical, Guest Memorial Reading Room and Library[64] in Dowlais, Wales.

The most significant of Barry's designs that were not carried out included, his proposed Law Courts (1840-41), that if built would have covered Lincoln's Inn Fields with a a large Greek Revival building, this rectangular building would have been over three hundred by four hundred feet, in a Greek Doric style, there would have been octastyle porticoes in the middle of the shorter sides and hexastyle porticoes on the longer sides, leading to a large central hall that would have been surrounded by twelve court rooms that in turn were surrounded by the ancillary facilities.[65] Later was his General Scheme of Metropolitan Improvements, that were exhibited in 1857.[66] This comprehensive scheme was for the redevelopment of much of Whitehall, Horse Guards Parade, the embankment of the River Thames on both sides of the river in the areas to the north and south of the Palace of Westminster, this would eventual be partially realised as the Victoria Embankment and Albert Embankment, three new bridges across the Thames, a vast Hotel where Charing Cross railway station was later built, the enlargement of the National Gallery (Barry's son Edward would later extend the Gallery) and new buildings around Trafalgar Square and along the new embankments and the recently created Victoria Street. There were also several new roads proposed on both sides of the Thames. The largest of the proposed buildings would have been even larger than the Palace of Westminster, this was the Government Offices, this vast building would have covered the area stretching from horse Guards Parade across Downing Street and the sites of the future Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the HM Treasury on Whitehall up to Parliament Square.[67] It would have had a vast glass-roofed hall, 320 by 150 feet, at the centre of the building. The plan was to house all government departments apart from the Admiralty in the building. The building would have been in a Classical style incorporating Barry's existing Treasury building.

Houses of Parliament

Following the destruction by fire of the existing Houses of Parliament on 16 October 1834, a competition was held to find a suitable design, for which there were 97 entries.[68] Barry's entry (number 64)[69] won the commission in January 1836 to design the new Palace of Westminster, working with Pugin (who designed furniture, stained glass, sculpture, wallpaper, decorative floor tiles, mosaic work etc.) on the Tudor Gothic building, the architectural style was chosen to complement the Henry VII Lady Chapel[70] opposite. The design had to incorporate those parts of the building that escaped destruction, most notably Westminster Hall, the adjoining double storey cloisters of St Stephen's court and the crypt of St Stephen's Chapel, Barry's design was parallel to the River Thames, but the surviving buildings are at a slight angle to the river, thus Barry had to incorporate this awkward difference in axis into the design. Although the design included most of the elements of the finished building, including the two towers at either end of the building, in would undergo significant redesign, the winning design was only about 650 feet in length about two-thirds the size of the finished building.[71] The central lobby and tower were later additions as were the extensive royal suite at the southern end of the building. The amended design on which construction commenced was approximately the same size as the finished building, although both the Victoria Tower and Clock Tower were considerably taller in the finished building and the Central Tower was not yet part of the design.[72]

Before construction could commence the site had to be embanked, and the site cleared of the remains of the buildings and various sewers diverted.[73] On 1 September 1837 work started on building a 920 foot long coffer-dam to enclose the building site along the river.[74] The construction of the embankment started on New Year's Day 1839.[75] The first work consisted of the construction of a vast concrete-raft to serve as the buildings foundation, after the foundations had been dug by hand,[74] 70,000 cubic yards of concrete were laid,[76] the site of the Victoria Tower was found to be of Quicksand, necessitating the use of piles.[76] The stone selected for the exterior of the building was quarried at Anston in Yorkshire,[75] the core of the walls are of brick.[76] In order to make the building as fire-proof as possible wood was not used structurally, only decoratively.[76] Cast iron was used extensively, for example the roofs of the building consist are of cast iron girders covered by sheets of iron,[77] cast iron beams were also used as joists to support the floors[78] and extensively in the internal structures of both the clock tower and Victoria tower.[79] Barry and his engineer Alfred Meeson were responsible for designing scaffolding, hoists and cranes used in the construction,[80] one of their most innovative developments was the scaffolding used to construct the three main towers. For the central tower they designed an inner rotating scaffold, surrounded by timber centring to support the masonry vault of the Central Lobby, that spans 57 feet 2 inches, and an external timber tower,[81] a portable steam engine was used to lift stone and brick to the upper parts of the tower.[82] When it came to build the Victoria and Clock towers it was decided to dispense with external scaffolding and lift building materials up through the towers by an internal scaffolding that traveled up the structure as it was built. The scaffold and cranes being powered by steam engines.[83]

Work on the actual building began with the laying of a foundation stone on 27 April 1840 by Barry's wife Sarah near the north-east corner of the building.[84] A major problem for Barry came with the appointment on 1 April 1840 of the ventilation expert Dr David Boswell Reid.[85] Reid, who Barry described as '..not profess to be thoroughly acquainted with the practical details of building and machinery'[86] would make increasing demands that affected the building's design, leading to delays in construction, by 1845 Barry refused to communicate with Reid except in writing. A direct result of Reid's demands led to the addition of the Central Tower to the building, it was designed to act as a giant chimney to draw fresh air through the building.[87]

The House of Lords was completed in April 1847,[88] the room is a double cube (90 x 45 x 45 feet)[88] and the House of Commons finished in 1852, where after he was created a Knight Bachelor. St. Stephen's Tower (the clock tower) is 316 feet tall and was completed in 1858[89] the Victoria Tower is 323 feet tall and completed in 1860,[90] the iron flagpole on the Victoria Tower tapers from two feet to nine inches in diameter and the iron crown on top is 3 feet 6 inches in diameter and 395 feet above ground.[91] The central tower is 261 feet high.[92] The building is 940 feet in length, the east Thames facade is 873 feet in length, it covers about eight acres of land and has over 1000 rooms.[93] A.W.N. Pugin later dismissed the building saying 'All Grecian, Sir, Tudor details on a classic body',[94] the essentially symmetrical plan and river front being offensive to Pugin's taste for medieval gothic buildings.

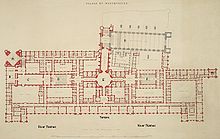

The plan[95] of the finished building is built around two major axes, at the southern end of Westminster Hall, St. Stephen's porch was created, as a major entrance to the building, this involved inserting a great arch with a grand stair case at the southern end of Westminster hall, this leads to the first floor where the major rooms are located. To the east of St. Stephens porch is St. Stephen's Hall, this is built on the surviving under-croft of St. Stephen's Chapel, to the east of this the octagonal Central Lobby (above which is the central tower) this is the centre of the building. North of the Central Lobby is the Commons' Corridor, this leads into the square Commons' Lobby, north of which is the House of commons, there are various offices and corridors to the north of the House of Commons with the clock tower terminating the northern axis of the building. South of the Central Lobby is the Peers' Corridor leading to the Peers' Lobby, south of which lies the House of Lords. South of the House of Lords in sequence are Prince's Chamber, Royal Gallery and Queen's Robing Room. To the north-west of the Queen's Robing Chamber if the Norman Porch to the west of which the Royal Staircase leads down to the Royal Entrance located immediately beneath the Victoria Tower. East of the Central Lobby is the East Corridor leading to the Lower Waiting Hall, to the east of which is the Members Dining Room located in the very centre of the east front. To the north of the Members Dining Room lies the House of Commons Library, and at the northern end of the east front is the projecting Speaker,s House, home of the Speaker of the House of Commons (United Kingdom), to the south of the Members Dining Room lies various committee rooms followed by House of Lords Library, projecting from the southern end of the facade is the Lord Chancellor's House home of The Lord Chancellor.

Although Parliament gave Barry a prestigious name in architecture, it near enough finished him off. The building was overdue, Barry had estimated it would take six years[96] and £724,986[97] (excluding the cost of the site, embankment and furnishings), its construction took twenty six years and was well over budget, by July 1854 the estimated cost was £2,166,846,[98] making Barry tired and stressed. The fully Barry design was never completed, the design would have enclosed New Palace Yard as an internal courtyard, the clock tower would have been in the north-east corner, with a great gateway in the north-west corner surmounted by the Albert Tower, and continuing south along the west front of Westminster Hall.[99]

Professional life

Barry was appointed architect to the Dulwich College estate in 1830, an appointment that last until 1858.[3] Barry attended the inaugural meeting of the Royal Institute of British Architects on 3 December 1834[100] he became a fellow of the R.I.B.A. and later served as Vice-President of the Institute, in 1859 he turned down the Presidency of the R.I.B.A.[3]

Barry also served on the Royal Commission (learned committee) developing plans for the Great Exhibition of 1851.[101] In 1852 he was an assessor on the committee that selected Cuthbert Brodrick's design in the competition to design Leeds Town Hall.[102] In 1853 Barry was consulted by Albert, Prince Consort on his plans for creation of what became know as Albertopolis.[103] Barry spent two months in Paris in 1855 representing, along with his friend and fellow architect Charles Robert Cockerell, English architecture on the juries of the Exposition Universelle (1855).[104]

Barry was an active fellow of the Royal Academy, and he was involved in revising the architectural curriculum in 1856.[105] In 1858 Barry was appointed to the St. Paul's Committee, whose function was to oversee the maintenance of the Special Evening Service in St Paul's Cathedral and carry out redecoration of the Cathedral.[106]

Several architects received their training in Barry's office, including: John Hayward, John Gibson, George Somers Leigh Clarke, J. A. Chatwin and his sons Charles Barry and Edward Middleton Barry.[107] Additionally Barry had several assistants who worked for him at various times, including Robert Richardson Banks, Thomas Allom, Peter Kerr and Ingress Bell.

Awards and recognition

- Barry was elected Associate of the Royal Academy in 1840, and to full membership in the following year.

- He was recognized by the main artistic bodies of many European countries, and was enrolled as a member of the academies of art in Rome (Accademia di San Luca) in 1842, Saint Petersburg (1845), Brussels (1847), Prussia (1849) and Stockholm (1850). He was later elected to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts.

- Fellow of the Royal Society in 1849.

- Awarded the RIBA Royal Gold Medal in 1850.

- Barry was knighted in 1852 by Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, marking the completion of the main interiors of the Palace of Westminster.

- After the foundation of the American Institute of Architects in 1857 Barry was elected a member.

Major projects

Barry also designed:

- All Saints' Church, Whitefield (1822–25)

- St Peter's Church, Brighton (1824–28)

- The Royal Institution of Fine Arts, Manchester, now Manchester Art Gallery (1824–35)

- New tower Petworth Church, Sussex (1827)

- The Royal Sussex County Hospital, Brighton (1828)

- Thomas Attree's villa and the Pepper Pot, Queen's Park, Brighton (1830)

- Travellers Club. Pall Mall, London (1830–32)

- Remodelling Dulwich College largely destroyed when rebuilt by Charles Barry, Jr. (1831)

- The Royal College of Surgeons, (the portico survives from George Dance the Younger's building) London (1834–36)

- Horsely Towers, East Horsley (1834)

- New gateway and entrance lodge plus alterations to the gardens Bowood House, Wiltshire (1834–38)

- Remodelling of Kingston Lacy, Dorset (1835–39)

- The Manchester Athenaeum (1837–39 – now also part of the Manchester Art Gallery)

- The Reform Club, London (1837 – next door to the Travellers)

- King Edward's School, New Street, Birmingham (1838)

- Lancaster House, London, interiors (1838–40)

- The Trafalgar Square precinct (1840)

- Pentonville (HM Prison), London, architectural features, overall design by Joshua Jebb (1841–42)

- Remodelling of Trentham Hall and creation of its Italianate gardens, north Staffordshire (1842)

- Remodelling (virtual rebuilding) of Highclere Castle, Hampshire (1842)

- Added wings and other remodelling, Duncombe Park, Yorkshire (1843–46)

- Holy Trinity Church, Hurstpierpoint, Sussex (1843–45)

- Remodelling of Harewood House, Yorkshire (1843–50)

- Lansdowne Monument, Cherhill, Wiltshire (1845)

- HM Treasury building in Whitehall (the remodelling of an earlier building br Sir John Soane) (1846–47)

- Bridgewater House, Westminster, London (1846–51)

- Canford Manor in Tudor Gothic, now Canford School, Dorset (1848–52)

- Cliveden House in Buckinghamshire (1850–51)

- Remodelling of Dunrobin Castle near Golspie, Scotland (1850)

- Remodelling of Shrubland Park and Italinate gardens, Suffolk (1850)

- Barristers' chambers at 1 Temple Gardens in Inner Temple

- Restoration of Gawthorpe Hall, near Burnley, Lancashire (1850–52)

- Halifax Town Hall, West Yorkshire (designed 1860; completed by Edward Middleton Barry, 1863)

Death and funeral

From 1837 Barry suffered from sudden bouts of illness,[108] one of the most severe being in 1858. On 12 May 1860 after an afternoon at the Crystal Palace with Lady Barry, at his home The Elms, Clapham Common, he was seized at eleven o'clock at night with difficulty in breathing and was in pain from a heart attack and died shortly after.[109]

His funeral and internment took place on 22 May in Westminster Abbey,[110] there were eight pall-bearers: Sir Charles Eastlake; William Cowper-Temple, 1st Baron Mount Temple; George Parker Bidder; Sir Edward Cust, 1st Baronet; Alexander Beresford Hope; The Dean of St. Paul's Henry Hart Milman; Charles Robert Cockerell and Sir William Tite.[111] There were several hundred mourners at the funeral service,[112] including his five sons, (it was against custom for women to attend, so neither his widow or daughters were present), his friend Mr Wolfe, numerous members of the House of Commons and Lords, attended, several who were his former clients, about 150 members of the R.I.B.A., including: Decimus Burton, Thomas Leverton Donaldson, Benjamin Ferrey, Charles Fowler, George Godwin, Owen Jones, Henry Edward Kendall, John Norton, Joseph Paxton, James Pennethorne, Anthony Salvin, Sydney Smirke, Lewis Vulliamy, Matthew Digby Wyatt and Thomas Henry Wyatt. Various members of the Royal Society, Royal Academy, Institute of Civil Engineers, Society for the Encouragement of Fine Art and Society of Antiquaries were present.[113] The funeral service was taken by the Dean of Westminster Abbey Richard Chenevix Trench.[114]

The Monumental brass marking Barry's tomb in the nave at Westminster Abbey[115] shows the Victoria Tower and Plan of the Palace of Westminster flanking a large Christian cross, beneath is this inscription:

Sacred to the memory of Sir Charles Barry, Knight R.A. F.R.S. & c. Architect of the New Palace of Westminster and other buildings who died the 12th May A.D. 1860 aged 64 years and lies buried beneath this brass.

Following Barry's death a life size marble sculpture (1861–65) of him was carved by John Henry Foley and was set up as a memorial to him at the foot of the Committee Stairs in the Palace of Westminster.[116] The figure is seated holding a large book resting in his lap held at the top in his left hand.

The next generation

Barry was engaged to Sarah Roswell (1798–1882) in 1817, they married on 7 December 1822[117] and had seven children together.

Four of Sir Charles Barry's five sons[118] followed in his career footsteps. Eldest son Charles Barry (junior) (1823–1900) designed Dulwich College and park in south London and rebuilt Burlington House (home of the Royal Academy) in central London's Piccadilly; Edward Middleton Barry (1830–1880) completed the Parliament buildings and designed the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden; Godfrey Walter Barry (1834–1868) became a surveyor; Sir John Wolfe-Barry (1836–1918) was the engineer for Tower Bridge and Blackfriars Railway Bridge. Edward and Charles also collaborated on the design of the Great Eastern Hotel at London's Liverpool Street station.

His second son, Rev. Alfred Barry (1826–1910), became a noted clergyman. He was headmaster of Leeds Grammar School from 1854 to 1862 and of Cheltenham College from 1862 to 1868. He later became the third Bishop of Sydney, Australia. He wrote a 400 page biography of his father, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry, R.A., F.R.S., that was published in 1867.

Barry's daughters were Emily Barry (1828–1886) and Adelaide Sarah Barry (1841–1907).

Sir Charles’ relative John Hayward designed several buildings including, The Hall, Chapel Quad Pembroke College, Oxford.[119]

References

- ^ a b c d e page 4, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ Dod, Robert P. (1860). The Peerage, Baronetage and Knightage of Great Britain and Ireland. London: Whitaker and Co.. p. 106.

- ^ a b c d page 123, Directory of British Architects 1834-1914 Volume 1:A-K, Antonia Brodie, Alison Felstead, Jonathan Franklin, Leslie Pinfield and Jane Oldfiled, 2nd edition 2001, Continuum, ISBN 0-8264-5513-1

- ^ page 7, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ pages 15-63, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 18, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 19, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 23, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ pages 23-25, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 27, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 29, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 31, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 33, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 34, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 98 The Exiled Collector: William Bankes and the Making of an English Country House, Anne Sebba, 2004, John Murray ISBN 0-7195-6328-3

- ^ a b c page 36, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 38, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 40, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 42, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 43, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 43, in the Rev. Alfred Barry. The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 46, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 49, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 67, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 324, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 324, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 324, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 5, Marcus Whiffen, The Architecture of Sir Charles Barry in Manchester and Neighbourhood, 1950, Council of the Royal Manchester Institution

- ^ Page 654, The Buildings of England, London 4: North, Bridget Cherry & Nikolaus Pevsner, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-14-071049-3

- ^ Page 656, The Buildings of England, London 4: North, Bridget Cherry & Nikolaus Pevsner, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-14-071049-3

- ^ Page 658, The Buildings of England, London 4: North, Bridget Cherry & Nikolaus Pevsner, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-14-071049-3

- ^ Whiffen 1950, page 14

- ^ page 429, The Buildings of England: Sussex, Ian Nairn and Nikolaus Pevsner, 1965, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-071028-0

- ^ page 541, The Buildings of England: Sussex, Ian Nairn and Nikolaus Pevsner, 1965, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-071028-0

- ^ pages 68-69, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 7, The Architecture of Sir Charles Barry in Manchester and Neighbourhood, Marcus Whiffen, 1950, Council of the Royal Manchester Institution

- ^ page 13, The Architecture of Sir Charles Barry in Manchester and Neighbourhood, Marcus Whiffen, 1950, Council of the Royal Manchester Institution

- ^ page 444, The Buildings of England: Sussex, Ian Nairn and Nikolaus Pevsner, 1965, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-071028-0

- ^ pages 455-456, The Buildings of England: Sussex, Ian Nairn and Nikolaus Pevsner, 1965, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-071028-0

- ^ pages 611-613, the Buildings of England: London 6 Westminster, Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09595-3

- ^ pages 129-132, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 16, The Architecture of Sir Charles Barry in Manchester and Neighbourhood, Marcus Whiffen, 1950, Council of the Royal Manchester Institution

- ^ page 311, the Buildings of England: London 6 Westminster, Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09595-3

- ^ page 92, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 422, Staffordshire, The Victorian Country House, Mark Girouard, 1979 2nd Edition, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02390-1

- ^ page 179, The English Garden, Richard Bisgrove, 1990, Viking, ISBN 0-670--8032-2

- ^ page 231, The Buildings of England: Staffordshire, Nikolaus Pevsner, 1974, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-071046-9

- ^ pages 121-123, The Buildings of England: Wiltshire, Nikolaus Pevsner and Bridget Cherry, 1975 2nd Edition, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-0710-26-4

- ^ page 75, The Obelisk A Monumental Feature in Britain, Richard Barnes, 2004, Frontier, ISBN 1-872914-28-4

- ^ pages 49-50, The Victorian Country House, Mark Girouard, 1979 2nd Edition, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02390-1

- ^ page 130, The Victorian Country House, Mark Girouard, 1979 2nd Edition, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02390-1

- ^ page 140, The Buildings of England: Yorkshire The North Riding, Nikolaus Pevsner, 1966, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-071009-9

- ^ page 125, Harewood House, Mary Mauchline, 1974, David and Charles, ISBN 0-7153-6416-2

- ^ page 430, The Victorian Country House, Mark Girouard, 1979 2nd Edition, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02390-1

- ^ page 127, The Buildings of England: Dorset, John Newman and Nikolaus Pevsner, 1972, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-071044-2

- ^ pages 417-418, The Buildings of England: Suffolk, Nikolaus Pevsner and Enid Radcliffe, 1974 2ND Edition, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-0710-20-5

- ^ page 180, The English Garden, Richard Bisgrove, 1990, Viking, ISBN 0-670--8032-2

- ^ page 493, The Buildings of England: Lancashire North, Clare Hartwell and Nikolaus Pevsner, 2009, Yale University Press ISBN 978-0-300-12667-9

- ^ pages 94-96, Clivden The Place and People, James Crathorne, 1995, Collins & Brown Ltd, ISBN 1-85585-223-3

- ^ page 181, The English Garden, Richard Bisgrove, 1990, Viking, ISBN 0-670--8032-2

- ^ a b c pages 257-258, the Buildings of England: London 6 Westminster, Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09595-3

- ^ pages 606-607, the Buildings of England: London 6 Westminster, Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09595-3

- ^ The Buildings of England: Yorkshire the West Riding, Nikolaud Pevsner and Enid Radcliffe, 1967 2nd Edition, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-071017-5

- ^ page 447, the Buildings of Wales:Glamorgan, John Newman, 1995, Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-071056-6

- ^ pages 53-55, The Law Courts: The Architecture of George Edmund Street, David B. Brownlee, 1984, M.I.T. Press, ISBN 0-262-02199-4

- ^ pages 292-301, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ pages 295-297, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 41, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 147, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 70, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ pages 42 to 43, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 76, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 97, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ a b page 197, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ a b page 98, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ a b c d page 198, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 200, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 199, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 204-205, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 212, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 209, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 211, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 211, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 101, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 102, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 103, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 103, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ a b page 79, Inside the House of Lords, Clive Aslet & Derry Moore, 1998, Haper Collins, ISBN 000-414-047-8

- ^ pages 217-218, the Buildings of England: London 6 Westminster, Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09595-3

- ^ pages 216-217, the Buildings of England: London 6 Westminster, Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09595-3

- ^ page 205, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 206, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ these statistics are from pages 258-259, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 221, Pugin A Gothic Passion, Paul Atterbury & Clive Wainwright (Editors), 1994, Yale University Press & Victoria and Albert Museum, ISBN 0-300-06012-2

- ^ pages 219-226, the Buildings of England: London 6 Westminster, Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09595-3

- ^ page 78, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 77, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ page 161, The Houses of Parliament, M.H. Port, 1976, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-02022-8

- ^ pages 289-292, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 311, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 14, The Crystal Palace, Patrick Beaver, 1986 2nd Edition, Phillimore & Co. Ltd, ISBN 0-85033-622-8

- ^ page 317, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ pages 358-369, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 315, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 306, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 319, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 90, A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects 1600-1840, Howard Colvin, 2nd Edition, 1978, John Murray Ltd, ISBN 0-7195-3328-7

- ^ page 340, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 341, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 342, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ pages 342-343, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 342, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ pages 343-344, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 345, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 351, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ page 227, the Buildings of England: London 6 Westminster, Simon Bradley and Nikolaus Pevsner, 2003, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09595-3

- ^ page 70, in the Rev. Alfred Barry, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ pages 326-327, in the Rev. Alfred Barry's, The Life and Times of Sir Charles Barry R.A., F.S.A., 1867, John Murray

- ^ "Villa E.1027, Cap Martin, Roquebrune". Royal Institute of British Architects. http://www.ribapix.com/index.php?a=advanced&s=item&key=XYToxOntzOjM6IjAwNCI7czo0OiIyMTg2Ijt9&pg=1. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Barry, Sir Charles". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Barry, Sir Charles". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

- Biography - Britain Express

- The History of St Peter's Church, Brighton

- Palace of Westminster

- Works by or about Charles Barry in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Papers of Charles Barry at the UK Parliamentary Archives

Categories:- 1795 births

- 1860 deaths

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- English architects

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Italianate architecture in the United Kingdom

- Knights Bachelor

- People from Westminster

- Recipients of the Royal Gold Medal

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.