- Royal Opera House

-

This article is about the opera house in London. For the post-1945 opera company, see Royal Opera, London. For other uses, see Royal Opera (disambiguation).

Royal Opera House

The Royal Opera House, Bow Street frontage with Plazzotta's statue, Young Dancer, in the foregroundAddress Bow Street City London Country  UK

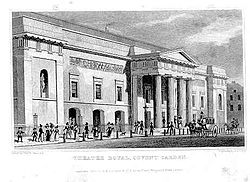

UKDesignation Grade I listed building Capacity 2,256 Type Opera House www.roh.org.uk The Royal Opera House is an opera house and major performing arts venue in Covent Garden, central London. The large building is often referred to as simply "Covent Garden", after a previous use of the site of the opera house's original construction in 1732. It is the home of The Royal Opera, The Royal Ballet, and the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House. Originally called the Theatre Royal, it served primarily as a playhouse for the first hundred years of its history. In 1734, the first ballet was presented. A year later, Handel's first season of operas began. Many of his operas and oratorios were specifically written for Covent Garden and had their premieres there.

The current building is the third theatre on the site following disastrous fires in 1808 and 1857. The façade, foyer, and auditorium date from 1858, but almost every other element of the present complex dates from an extensive reconstruction in the 1990s. The Royal Opera House seats 2,256 people and consists of four tiers of boxes and balconies and the amphitheatre gallery. The proscenium is 12.20 m wide and 14.80 m high. The main auditorium is a Grade 1 listed building.

Contents

The Davenant Patent

"Rich's Glory": John Rich takes over (seemingly invades) his new Covent Garden Theatre. (A caricature by William Hogarth)

"Rich's Glory": John Rich takes over (seemingly invades) his new Covent Garden Theatre. (A caricature by William Hogarth)

The foundation of the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden lies in the letters patent awarded by Charles II to Sir William Davenant in 1660, allowing Davenant to operate one of only two patent theatre companies (The Duke's Company) in London. The letters patent remained in the possession of the Opera House until shortly after the First World War, when the document was sold to an American university library.

The first theatre

In 1728, John Rich, actor-manager of the Duke's Company at Lincoln's Inn Fields Theatre, commissioned The Beggar's Opera from John Gay. The success of this venture provided him with the capital to build the Theatre Royal (designed by Edward Shepherd) at the site of an ancient convent garden, part of which had been developed by Inigo Jones in the 1630s with a piazza and church. In addition, a Royal Charter had created a fruit and vegetable market in the area, a market which survived in that location until 1974. At its opening on 7 December 1732, Rich was carried by his actors in processional triumph into the theatre for its opening production of William Congreve's The Way of the World.[1]

During the first hundred years or so of its history, the theatre was primarily a playhouse, with the Letters Patent granted by Charles II giving Covent Garden and Theatre Royal, Drury Lane exclusive rights to present spoken drama in London. Despite the frequent interchangeability between the Covent Garden and Drury Lane companies, competition was intense, often presenting the same plays at the same time. Rich introduced pantomime to the repertoire, himself performing (under the stage name John Lun, as Harlequin) and a tradition of seasonal pantomime continued at the modern theatre, until 1939.[2]

In 1734, Covent Garden presented its first ballet, Pygmalion. Marie Sallé discarded tradition and her corset and danced in diaphanous robes.[3] George Frideric Handel was named musical director of the company, at Lincoln's Inn Fields, in 1719, but his first season of opera, at Covent garden, was not presented until 1734. His first opera was Il pastor fido followed by Ariodante (1735), the première of Alcina, and Atalanta the following year. There was a royal performance of the Messiah in 1743, which was a success and began a tradition of Lenten oratorio performances. From 1735 until his death in 1759 he gave regular seasons there, and many of his operas and oratorios were written for Covent Garden or had their first London performances there. He bequeathed his organ to John Rich, and it was placed in a prominent position on the stage, but was among many valuable items lost in a fire that destroyed the theatre in 1808. In 1792[4] the architect Henry Holland rebuilt the auditorium, this was within the existing shell of the building but deeper and wider than the old auditorium, thus increasing capacity.

The second theatre

Rebuilding began in December 1808, and the second Theatre Royal, Covent Garden (designed by Robert Smirke) opened on 18 September 1809 with a performance of Macbeth followed by a musical entertainment called The Quaker. The actor-manager John Philip Kemble, raised seat prices to help recoup the cost of rebuilding, but the move was so unpopular that audiences disrupted performances by beating sticks, hissing, booing and dancing. The Old Price Riots lasted over two months, and the management was finally forced to accede to the audience's demands.[5]

During this time, entertainments were varied; opera and ballet were presented, but not exclusively. Kemble engaged a variety of acts, including the child performer Master Betty; the great clown Joseph Grimaldi made his name at Covent Garden. Many famous actors of the day appeared at the theatre, including the tragediennes Sarah Siddons and Eliza O'Neill, the Shakespearean actors William Charles Macready, Edmund Kean and his son Charles. On 25 March 1833 Edmund Kean collapsed on stage while playing Othello, and died two months later.[6]

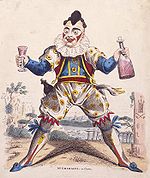

Joseph Grimaldi, as clown (contemporary print)

Joseph Grimaldi, as clown (contemporary print)

In 1806, the pantomime clown Joseph Grimaldi (The Garrick of Clowns) had performed his greatest success in Harlequin and Mother Goose; or the Golden Egg at Covent Garden, and this was subsequently revived, at the new theatre. Grimaldi was an innovator: his performance as Joey introduced the clown to the world, building on the existing role of Harlequin derived from the Commedia dell'arte. His father had been ballet-master at Drury Lane, and his physical comedy, his ability to invent visual tricks and buffoonery, and his ability to poke fun at the audience were extraordinary.[7]

Early pantomimes were performed as mimes accompanied by music, but as Music hall became popular, Grimaldi introduced the pantomime dame to the theatre and was responsible for the tradition of audience singing. By 1821 dance and clowning had taken such a physical toll on Grimaldi that he could barely walk, and he retired from the theatre.[8] By 1828, he was penniless, and Covent Garden held a benefit concert for him.

In 1817, bare flame gaslight had replaced the former candles and oil lamps that lighted the Covent Garden stage. This was an improvement, but in 1837 Macready employed limelight in the theatre for the first time, during a performance of a pantomime, Peeping Tom of Coventry. Limelight used a block of quicklime heated by an oxygen and hydrogen flame. This allowed the use of spotlights to highlight performers on the stage.[9]

The Theatres Act 1843 broke the patent theatres' monopoly of drama. At that time Her Majesty's Theatre in the Haymarket was the main centre of ballet and opera but after a dispute with the management in 1846 Michael Costa, conductor at Her Majesty's, transferred his allegiance to Covent Garden, bringing most of the company with him. The auditorium was completely remodelled and the theatre reopened as the Royal Italian Opera on 6 April 1847 with a performance of Rossini's Semiramide.[10]

In 1852, Louis Antoine Jullien the French eccentric composer of light music and conductor presented an opera of his own composition, Pietro il Grande. Five performances were given of the 'spectacular', including live horses on the stage and very loud music. Critics considered it a complete failure and Jullien was ruined and fled to America.[11][12] Costa and his successors presented all operas in Italian, even those originally written in French, German or English, until 1892, when Gustav Mahler presented the debut of Wagner's Ring cycle. The word "Italian" was then quietly dropped from the name of the opera house.[13]

The third theatre

On 5 March 1856, the theatre was again destroyed by fire. Work on the third theatre, designed by Edward Middleton Barry, started in 1857 and the new building, which still remains as the nucleus of the present theatre, was built by Lucas Brothers[14] and opened on 15 May 1858 with a performance of Meyerbeer's Les Huguenots.

The Royal English Opera company under the management of Louisa Pyne and William Harrison, made their last performance at Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on 11 December 1858 and took up residence at the theatre on 20 December 1858 with a performance of Michael Balfe's Satanella[15] and continued at the theatre until 1864.

The theatre became the Royal Opera House (ROH) in 1892, and the number of French and German works in the repertory increased. Winter and summer seasons of opera and ballet were given, and the building was also used for pantomime, recitals and political meetings.

During the First World War, the theatre was requisitioned by the Ministry of Works for use as a furniture repository.

From 1934 to 1936, Geoffrey Toye was Managing Director, working alongside the Artistic Director, Sir Thomas Beecham. Despite early successes, Toye and Beecham eventually fell out, and Toye resigned.[16]

During the Second World War the ROH became a dance hall. There was a possibility that it would remain so after the war but, following lengthy negotiations, the music publishers Boosey & Hawkes acquired the lease of the building. David Webster was appointed General Administrator, and Sadler's Wells Ballet was invited to become the resident ballet company. The Covent Garden Opera Trust was created and laid out plans "to establish Covent Garden as the national centre of opera and ballet, employing British artists in all departments, wherever that is consistent with the maintenance of the best possible standards…"[17]

The Royal Opera House reopened on 20 February 1946 with a performance of The Sleeping Beauty in an extravagant new production designed by Oliver Messel. Webster, with his music director Karl Rankl, immediately began to build a resident company. In December of 1946, they shared their first production, Purcell's The Fairy-Queen, with the ballet company. On 14 January 1947, the Covent Garden Opera Company gave its first performance of Bizet's Carmen.

Before the grand opening the Royal Opera House presented one of the Robert Mayer Children's concerts on Saturday, 9 February 1946.

Reconstruction in the 1990s

Several renovations had taken place to parts of the house in the 1960s, including improvements to the amphitheatre and an extension in the rear, but the theatre clearly needed a major overhaul. In 1975 the Labour government gave land adjacent to the Royal Opera House for a long-overdue modernisation, refurbishment, and extension. By 1995, sufficient funds had been raised to enable the company to embark upon a major reconstruction of the building by Carillion,[18] which took place between 1996 and 2000, under the chairmanship of Sir Angus Stirling. This involved the demolition of almost the whole site including several adjacent buildings to make room for a major increase in the size of the complex. The auditorium itself remained, but well over half of the complex is new.

The design team was led by Jeremy Dixon and Edward Jones of Dixon Jones BDP as architects. The acoustic designers were Rob Harris and Jeremy Newton of Arup Acoustics. The building engineer was Arup.

The new building has the same traditional horseshoe-shaped auditorium as before, but with greatly improved technical, rehearsal, office, and educational facilities, a new studio theatre called the Linbury Theatre, and much more public space. The inclusion of the adjacent old Floral Hall, long a part of the old Covent Garden Market but in general disrepair for many years, into the actual opera house created a new and extensive public gathering place. The venue is now claimed by the ROH to be the most modern theatre facility in Europe.

Surtitles, projected onto a screen above the proscenium, are used for all opera performances. Also, the electronic libretto system provides translations onto small video screens for some seats, and additional monitors and screens are to be introduced to other parts of the house.

Facilities

Paul Hamlyn Hall

The Paul Hamlyn Hall is a large iron and glass structure adjacent to, and with direct access to, the main opera house building. Historically, it formed part of the old Covent Garden flower market, and is still commonly known as the 'floral hall', but it was absorbed into the Royal Opera House complex during the 90s redevelopment. The hall now acts as the atrium and main public area of the opera house, with a champagne bar, restaurant and other hospitality services, and also providing access to the main auditorium at all levels.

The redevelopment of the Floral Hall was originally made possible with a pledge of £10m from the philanthropist Alberto Vilar and for a number of years, it was known as the Vilar Floral Hall; however Vilar failed to make good his pledge. As a result, the name was changed in September 2005 to the Paul Hamlyn Hall, after the opera house received a donation of £10m from the estate of Paul Hamlyn, towards its education and development programmes.

As well as acting as a main public area for performances in the main auditorium, the Paul Hamlyn Hall is also used for hosting a number of events, including private functions, dances, exhibitions, concerts, and workshops.[19]

Linbury Studio Theatre

The Linbury Studio Theatre is a flexible, secondary performance space, constructed below ground level within the Royal Opera House. With retractable raked seating and a floor which can be raised or lowered to form a stage, the theatre can accommodate up to 400 patrons and host a variety of different events. The theatre has been used for private functions, traditional theatre shows, and concerts, as well as community and educational events, product launches, dinners and exhibitions, etc. The Linbury Studio Theatre is one of the most technologically advanced performance venues in London and has its own public areas, including a bar and cloakroom.[20][21]

The Linbury Studio Theatre is most notable for hosting performances of experimental and independent dance and music, by independent companies and as part of the ROH2, the contemporary producing arm of the Royal Opera House. The Linbury Studio Theatre regularly stages performances by the Royal Ballet School and also hosts the Young British Dancer of the Year competition.

The Linbury Studio Theatre was constructed as part of the 90s redevelopment of the Royal Opera House. It is named in recognition of donations made by the Linbury Trust towards the redevelopment. The Trust is operated by Lord Sainsbury of Preston Candover and his wife Anya Linden, a former dancer with the Royal Ballet. The name Linbury is derived from the names Linden and Sainsbury.[22]

The Linbury Studio Theatre was opened in 1999 with a collaboration from three Croydon secondary schools (including Coloma school for girls and Edenham High school) in a original performance called 'About Face'.

High House Production Park (High House, Purfleet)

The Royal Opera House opened a scenery-making facility for their operas and ballets at High House Purfleet, Essex on 6 December 2010. The building was designed by Nicholas Hare Architects.[23] The East of England Development Agency, which partly funded developments on the park, notes that "the first phase includes the Royal Opera House’s Bob and Tamar Manoukian Production Workshop and Community areas".[23]

By the end of construction, estimated to be in 2012,[23] this will include the National Skills Academy for Creative & Cultural Skills, teaching practical skills to work in theatre, stage, and music productions.[24]

Opera at the Royal Opera House after 1945

For events in the history of opera at Covent Garden after 1945, see Royal Opera, London.Ballet at the Royal Opera House After 1945

For events in the history of ballet at Covent Garden after 1945, see Royal Ballet, London.References

- Notes

- ^ Admission to the 55 boxes was 5 shillings (1/4 £), half a crown (1/8 £) to the 'pit', and the gallery cost one shilling (1/20 £). A seat on the stage cost ten shillings. It was allowed to send servants to arrive at three to save places on the stage for their masters and mistresses. £115 was taken at the box office on the first night.

- ^ John Rich as Harlequin (PeoplePlayUK - Theatre Museum) accessed 22 July 2008.

- ^ Early ballet history (North Eastern University) accessed 22 December 2006.

- ^ page 91, Survey of London Volume XXXV: The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane and the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, F.H.W. Sheppard (Ed), 1970 The Athlone Press

- ^ The Old Price Riots (PeoplePlayUK - the Theatre Museum (at the V & A) accessed 01 July 2006.

- ^ Edmund Kean (1789–1833) (NNDB) accessed 22 July 2008.

- ^ Early Pantomime (PeoplePlayUK - the Theatre Museum (at the V & A) accessed 22 July 2008.

- ^ "Boz" (ed.) (Charles Dickens), Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi, 1853 edition with Notes and Additions by Charles Whitehead, accessed 22 Feb 2007.

- ^ Banham, Martin The Cambridge Guide to Theatre pp. 1026 (Cambridge University Press, 1995) ISBN 0521434378.

- ^ Discover the History of the Royal Opera House (Royal Opera House) accessed 22 July 2008.

- ^ Louis-Antoine Jullien (in French) accessed 21 Dec 2007.

- ^ Louis Antoine Jullien (Biography in Encyclopædia Britannica 1911) accessed 21 Dec 2007.

- ^ Gordon-Powell, Robin. Ivanhoe, full score, Introduction, vol. I, p. VIII, 2008, The Amber Ring

- ^ Charles Thomas Lucas at Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Reviews, "Drury-Lane Theatre", The Times, 13 December 1858, p. 10.

- ^ Jefferson, Alan, Sir Thomas Beecham: a Centenary Tribute, London: Macdonald and Jane's, 1979 ISBN 0-354-04205-x.

- ^ Rosenthal, see below.

- ^ Royal Opera House case study.

- ^ £10m pledged to Royal Opera House

- ^ Linbury Studio Theatre

- ^ Royal Opera House

- ^ The Linbury Trust

- ^ a b c "Thurrock launches new creative and cultural hub", 13 December 2010, East of England Development Agency press release on its website eeda.org.uk Retrieved 9 January 2011

- ^ Information (with illustration) about the Production Park from blog.roh.org.uk Retrieved 25 November 2010

- Further reading

- Allen, Mary, A House Divided, Simon & Schuster, 1998.

- Beauvert, Thierry, Opera Houses of the World, The Vendome Press, New York, 1995.

- Donaldson, Frances, The Royal Opera House in the Twentieth Century, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 1988.

- Earl, John and Sell, Michael Guide to British Theatres 1750-1950, pp. 136–8 (Theatres Trust, 2000) ISBN 0-7136-5688-3.

- Haltrecht, Montague,The Quiet Showman: Sir David Webster and the Royal Opera House, Collins, London, 1975.

- Lebrecht, Norman, Covent Garden: The Untold Story: Dispatches from the English Culture War, 1945-2000, Northeastern University Press, 2001.

- Lord Drogheda, et al., The Covent Garden Album, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1981.

- Mosse, Kate, The House: Inside the Royal Opera House Covent Garden, BBC Books, London, 1995.

- Rosenthal, Harold, Opera at Covent Garden, A Short History, Victor Gollancz, London, 1967.

- Tooley, John, In House: Covent Garden, Fifty Years of Opera and Ballet, Faber and Faber, London, 1999.

- Thubron, Colin (text) and Boursnell, Clive (photos), The Royal Opera House Covent Garden, Hamish Hamilton, London, 1982.

External links

- Royal Opera House official website

- Royal Opera House Collections Online (Archive Collections Catalogue and Performance Database)

- Royal Opera House elevation

- The Royal Ballet School official website

- Select Committee on Culture, Media and Sport's 1998 Report on funding and management issues at the Royal Opera House

- Theatre History Articles, Images, and Archive Material

Coordinates: 51°30′46.41″N 00°07′21.96″W / 51.5128917°N 0.1227667°W

Categories:- The Royal Ballet

- Opera houses in the United Kingdom

- Opera in London

- Grade I listed buildings in London

- Grade I listed theatres

- Theatres in Westminster

- 1660 establishments in England

- Buildings and structures completed in 1858

- Ballet venues

- Covent Garden

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.