- Coumarin

-

Not to be confused with coumadin or dicoumarol.This article is about the sweet-smelling plant substance called coumarin. For the anticoagulant rodenticide poisons often called "coumarins" or "coumadins", see 4-hydroxycoumarins.

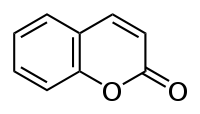

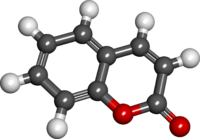

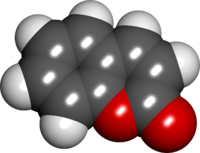

Coumarin

2H-chromen-2-oneOther names1-benzopyran-2-one

2H-chromen-2-oneOther names1-benzopyran-2-oneIdentifiers CAS number 91-64-5

PubChem 323 ChemSpider 13848793

UNII A4VZ22K1WT

DrugBank DB04665 KEGG D07751

ChEBI CHEBI:28794

ChEMBL CHEMBL6466

Jmol-3D images Image 1 - c1ccc2c(c1)ccc(=O)o2

Properties Molecular formula C9H6O2 Molar mass 146.14 g mol−1 Exact mass 146.036779 Density 0.935 g/cm3 (20 °C) Melting point 71 °C, 344 K, 160 °F

Boiling point 301 °C, 574 K, 574 °F

(verify) (what is:

(verify) (what is:  /

/ ?)

?)

Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa)Infobox references Coumarin (

/ˈkuːmərɪn/; 2H-chromen-2-one) is a fragrant chemical compound in the benzopyrone chemical class, found in many plants, notably in high concentration in the tonka bean (Dipteryx odorata), vanilla grass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), sweet woodruff (Galium odoratum), mullein (Verbascum spp.), sweet grass (Hierochloe odorata), cassia cinnamon (Cinnamomum aromaticum) and sweet clover (Fabaceae spp.). The name comes from a French word, coumarou, for the tonka bean. It has a sweet odor, readily recognised as the scent of newly-mown hay, and has been used in perfumes since 1882. Sweet woodruff, sweet grass and sweet clover in particular are named for their sweet smell, which is due to their high content of this substance. It has been used as an aroma enhancer in pipe tobaccos and certain alcoholic drinks, although in general it is banned as a flavorant food additive, due to concerns about hepatotoxicity coumarin causes in animal models. When it occurs in high concentrations in forage plants, coumarin is a somewhat bitter-tasting appetite suppressant, and is presumed to be produced by plants as a defense chemical to discourage predation.

/ˈkuːmərɪn/; 2H-chromen-2-one) is a fragrant chemical compound in the benzopyrone chemical class, found in many plants, notably in high concentration in the tonka bean (Dipteryx odorata), vanilla grass (Anthoxanthum odoratum), sweet woodruff (Galium odoratum), mullein (Verbascum spp.), sweet grass (Hierochloe odorata), cassia cinnamon (Cinnamomum aromaticum) and sweet clover (Fabaceae spp.). The name comes from a French word, coumarou, for the tonka bean. It has a sweet odor, readily recognised as the scent of newly-mown hay, and has been used in perfumes since 1882. Sweet woodruff, sweet grass and sweet clover in particular are named for their sweet smell, which is due to their high content of this substance. It has been used as an aroma enhancer in pipe tobaccos and certain alcoholic drinks, although in general it is banned as a flavorant food additive, due to concerns about hepatotoxicity coumarin causes in animal models. When it occurs in high concentrations in forage plants, coumarin is a somewhat bitter-tasting appetite suppressant, and is presumed to be produced by plants as a defense chemical to discourage predation.Although coumarin itself has no anticoagulant properties, it is transformed into the natural anticoagulant dicoumarol by a number of species of fungi. This occurs as the result of the production of 4-hydroxycoumarin, then further (in the presence of naturally occurring formaldehyde) into the actual anticoagulant dicoumarol, a fermentation product and mycotoxin. This substance was responsible for the bleeding disease known historically as "sweet clover disease" in cattle eating moldy sweet clover silage.[1]

Coumarin is used in the pharmaceutical industry as a precursor molecule in the synthesis of a number of synthetic anticoagulant pharmaceuticals similar to dicoumarol, the notable ones being warfarin (tradenamed "Coumadin," not to be confused with coumarin) and some even more potent rodenticides that work by the same anticoagulant mechanism. See 4-hydroxycoumarin and the relevant section of vitamin K antagonists for a discussion and listing of this class of drugs. All of these agents were historically discovered by analyzing sweet clover disease.

Coumarin has clinical medical value by itself, as an edema modifier. Coumarin and other benzopyrones, such as 5,6 benzopyrone, 1,2 benzopyrone, diosmin, and others, are known to stimulate macrophages to degrade extracellular albumen, allowing faster resorption of edematous fluids.[2][3]. Other biological activities that may lead to other medical uses have been suggested, with varying degrees of evidence.

Coumarin is also used as a gain medium in some dye lasers[4][5][6], and as a sensitizer in older photovoltaic technologies[7].

Contents

Synthesis

The biosynthesis of coumarin in plants is via hydroxylation, glycolysis, and cyclization of cinnamic acid. Coumarin can be prepared in a laboratory in a Perkin reaction between salicylaldehyde and acetic anhydride.

The Pechmann condensation provides another synthesis of coumarin and its derivatives.

Biological function

Coumarin has appetite-suppressing properties, suggesting one reason for its widespread occurrence in plants, especially grasses and clovers, is because of its effect of reducing the impact of grazing animals on these forages. Although the compound has a pleasant sweet odor and is responsible for the names of sweet clover and sweet grass, these plants are not named for their taste. Coumarin has a bitter taste, and animals will avoid it, if possible.[8]

Derivatives

Coumarin and its derivatives are all considered phenylpropanoids.

Some naturally occurring coumarin derivatives include umbelliferone (7-hydroxycoumarin), aesculetin (6,7-dihydroxycoumarin), herniarin (7-methoxycoumarin), psoralen and imperatorin.

4-Phenylcoumarin is the backbone of the neoflavones, a type of neoflavonoids.

Medical use

Coumarins have shown some evidence of many biological activities, although they are approved for few medical uses as pharmaceuticals. The activity reported for coumarin and coumarins includes anti-HIV, anti-tumor, anti-hypertension, anti-arrhythmia, anti-inflammatory, anti-osteoporosis, antiseptic, and analgesic (pain relief). It is also used in the treatment of asthma.[9] Coumarin has been used in the treatment of lymphedema.[10]

Toxicity and use in foods, beverages, tobacco, and cosmetics

Coumarin is moderately toxic to the liver and kidneys, with a "Median Lethal Dose" (LD50) of 275 mg/kg — low compared to related compounds. Although only somewhat dangerous to humans, coumarin is a potent rodenticide: Rats and other rodents metabolize it largely to 3,4-coumarin epoxide, a toxic compound that can cause internal hemorrhage and death. Humans metabolize it largely to 7-hydroxycoumarin, a compound of lower toxicity. The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment has established a "tolerable daily intake" (TDI) of 0.1 mg coumarin per kg body weight, but also advises, [if] this level is exceeded for a short time only, there is no threat to health.[11] For example, a person weighing 135 lbs or about 61 kg would have a TDI of approximately 6.1 mg of coumarin.

European health agencies have warned against consuming high amounts of cassia bark, one of the four species of cinnamon, because of its coumarin content.[12] According to the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, 1 kg of (cassia) cinnamon powder contains approximately 2.1 to 4.4 g of coumarin.[13] Powdered Cassia Cinnamon weighs 0.56 g/cc;[14] therefore, 1 kg of Cassia Cinnamon powder is equal to 362.29 teaspoons (1000 g divided by 0.56 g/cc multiplied by 0.20288 tsp/cc). This means 1 teaspoon of cinnamon powder contains 5.8 to 12.1 mg of coumarin, which may be above the Tolerable Daily Intake for smaller individuals.[13] However, it is important to note that the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment only cautions against high daily intakes of foods containing coumarin. Chamomile, a common herbal tea, also contains coumarin.

Coumarin is often found in tobacco products and artificial vanilla substitutes, despite having been banned as a food additive in numerous countries since the mid-20th century. Coumarin was banned as a food additive in the United States in 1954, largely because of hepatotoxicity results in rodents.[15] OSHA considers this compound to be only a lung-specific carcinogen, and "not classifiable as to its carcinogenicity to humans".[16] Coumarin was banned as an adulterant in cigarettes by tobacco companies in 1997, but due to the lack of reporting requirements to the US Department of Health and Human Services it was still being used as a flavoring additive in pipe tobacco.[citation needed] Coumarin is currently listed by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) among "Substances Generally Prohibited From Direct Addition or Use as Human Food", according to 21 CFR 189.130,[17][18] but some natural additives containing coumarin, such as sweet woodruff (Galium odoratum) due to its coumarin odor, are allowed "in alcoholic beverages only" (21 CFR 172.510).[19] In Europe, such beverages are very popular, for example Maiwein (white wine with woodruff) and Żubrówka (vodka flavoured with bison grass). However, the coumarin content of these drinks is said to cause headaches.

Coumarin should be avoided by people with perfume allergy.[20]

Related compounds and derivatives

Compounds derived from coumarin are also called coumarins or coumarinoids; this family includes:

- brodifacoum[21][22]

- bromadiolone[23]

- coumafuryl[24]

- difenacoum[25]

- auraptene

- ensaculin

- phenprocoumon (Marcoumar)

- Scopoletin can be isolated from the bark of Shorea pinanga[26]

- warfarin

Use as pesticides

Many of the above-stated compounds (to be specific, the 4-hydroxycoumarins, sometimes loosely called coumarins) are used as anticoagulant drugs and/or as rodenticides, which work by the anticoagulant mechanism. They block the regeneration and recycling of vitamin K. These chemicals are sometimes also incorrectly referred to as "coumadins" rather than 4-hydroxycoumarins (Coumadin™ is a brand name for warfarin).

Some of the 4-hydroxycoumarin anticoagulant class of chemicals are designed to have very high potency and long residence times in the body, and these are used specifically as poison rodenticides. Death occurs after a period of several days to two weeks, usually from internal hemorrhaging.

Vitamin K is a true antidote for poisoning by these antirodenticide 4-hydroxycoumarins such as bromadiolone. Treatment usually comprises a large dose of vitamin K given intravenously immediately, followed by doses in pill form for a period of at least two weeks, though usually three to four, afterwards. Treatment may even continue for several months. If caught early, the prognosis is good, even when large amounts are ingested. In the short term, transfusion with fresh frozen plasma to provide clotting factors, provides time for vitamin K to reverse enzyme poisoning in the liver, and allow new clotting factors to be synthesized there.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ^ Bye, A., King, H. K., 1970. The biosynthesis of 4-hydroxycoumarin and dicoumarol by Aspergillus fumigatus Fresenius. Biochemical Journal 117, 237-245.

- ^ full content of NEJM article. Treatment of Lymphedema of the Arms and Legs with 5,6-Benzo-[alpha]-pyrone. John R. Casley-Smith, Robert Gwyn Morgan, and Neil B. Piller Volume 329:1158-1163 October 14, 1993 Number 16.

- ^ Review of benzypyrone drugs and edema

- ^ F. P. Schäfer (Ed.), Dye Lasers, 3rd Ed. (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, 1990).

- ^ F. J. Duarte and L. W. Hillman (Eds.), Dye Laser Principles (Academic, New York, 1990).

- ^ F. J. Duarte, Tunable Laser Optics (Elsevier-Academic, New York, 2003) Appendix of Laser Dyes.

- ^ U.S. Pat. No. 4175982 to Loutfy et al, issued Nov 27 1978 to Xerox Corp.

- ^ Link KP (1 January 1959). "The discovery of dicumarol and its sequels". Circulation 19 (1): 97–107. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.19.1.97. PMID 13619027. http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/reprint/19/1/97.

- ^ Liu H., "Extraction and Isolation of compounds from Herbal medicines" in 'Traditional Herbal Medicine Research Methods', ed by Willow JH Liu 2011 John Wiley and Sons, Inc

- ^ Farinola, Nicholas; Piller, Neil (June 1, 2005). "Pharmacogenomics: Its Role in Re-establishing Coumarin as Treatment for Lymphedema". Lymphatic Research and Biology 3 (2): 81–86. doi:10.1089/lrb.2005.3.81. PMID 16000056.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions about coumarin in cinnamon and other foods" (PDF). The German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment. 30 October 2006. http://www.bfr.bund.de/cm/279/frequently_asked_questions_about_coumarin_in_cinnamon_and_other_foods.pdf.

- ^ NPR: German Christmas Cookies Pose Health Danger

- ^ a b High daily intakes of cinnamon: Health risk cannot be ruled out. BfR Health Assessment No. 044/2006, 18 August 2006

- ^ Engineering Resources - Bulk Density Chart

- ^ [1] Economic Botany Volume 41, Number 1, 41-47, 1986 DOI: 10.1007/BF02859345 Coumarin in vanilla extracts: Its detection and significance Robin J. Marles, CÉsar M. Compadre and Norman R. Farnsworth.

- ^ http://www.osha.gov/dts/chemicalsampling/data/CH_229620.html

- ^ http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_06/21cfr189_06.html

- ^ http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/~dms/eafus.html

- ^ http://www.access.gpo.gov/nara/cfr/waisidx_06/21cfr172_06.html

- ^ Survey and health assessment of chemical substances in massage oils

- ^ International Programme on Chemical Safety. "Brodifacoum (pesticide data sheet)". http://www.inchem.org/documents/pds/pds/pest57_e.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ Laposata M, Van Cott EM, Lev MH. (2007). Case 1-2007—A 40-Year-Old Woman with Epistaxis, Hematemesis, and Altered Mental Status. 356. pp. 174–82. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/356/2/174.

- ^ International Programme on Chemical Safety. "Bromadiolone (pesticide data sheet)". http://www.inchem.org/documents/pds/pds/pest88_e.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ Compendium of Pesticide Common Names. "Coumafuryl data sheet". http://www.alanwood.net/pesticides/coumafuryl.html. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ^ International Programme on Chemical Safety. "Difenacoum (health and safety guide)". http://www.inchem.org/documents/hsg/hsg/hsg095.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-14.

- ^ A modified oligostilbenoid, diptoindonesin C, from Shorea pinanga Scheff. Yana M. Syah; Euis H. Hakim; Emilio L. Ghisalberti; Afghani Jayuska; Didin Mujahidin; Sjamsul A. Achmad, Natural Product Research, Volume 23, Issue 7 October 2009

External links

Phenylpropanoids Hydroxycinnamic acids | Chromones (Furanochromones) | Cinnamaldehydes | Monolignols | Coumarins | Flavonoids | Phenylpropenes | Stilbenoids | Lignans | Lignins | Suberinsglycosides Aesculin | Skimmin (7-O-β-D-glucopyranosylumbelliferone) | ScopolinFuran derivatives Furanocoumarins (Angelicin | Apterin | Bergamottin | Bergapten | Imperatorin | Marmesin | Methoxsalen | Psoralen | Trioxsalen) | FuranochromonesMonoterpene coumarin ether Synthetic or drugs Categories:- Types of phenylpropanoids

- Fluorescent dyes

- Fuel dyes

- Laser gain media

- Coumarins

- Plant toxins

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.