- Rhotic and non-rhotic accents

-

English pronunciation can be divided into two main accent groups: a rhotic (pronounced /ˈroʊtɨk/, sometimes /ˈrɒtɨk/) speaker pronounces a rhotic consonant in words like hard; a non-rhotic speaker does not. That is, rhotic speakers pronounce /r/ in all positions, while non-rhotic speakers pronounce /r/ only if it is followed by a vowel sound in the same phrase or prosodic unit (see "linking and intrusive R").

In linguistic terms, non-rhotic accents are said to exclude the sound [r] from the syllable coda before a consonant or prosodic break. This is commonly (if misleadingly) referred to as "post-vocalic R".

Development of non-rhotic accents

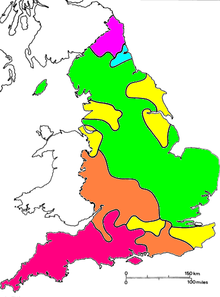

On this map of England, the red areas are where the rural accents were rhotic in the 1950s. Based on H. Orton et al., Survey of English Dialects (1962–71). Some areas with partial rhoticity (for example parts of the East Riding of Yorkshire) are not shaded on this map.

On this map of England, the red areas are where the rural accents were rhotic in the 1950s. Based on H. Orton et al., Survey of English Dialects (1962–71). Some areas with partial rhoticity (for example parts of the East Riding of Yorkshire) are not shaded on this map.

The earliest traces of a loss of /r/ in English are found in the environment before /s/ in spellings from the mid-15th century: the Oxford English Dictionary reports bace for earlier barse (today "bass", the fish) in 1440 and passel for parcel in 1468. In the 1630s, the word juggernaut is first attested, which represents the Sanskrit word jagannāth, meaning "lord of the universe". The English spelling uses the digraph er to represent a Hindi sound close to the English schwa. Loss of coda /r/ apparently became widespread in southern England during the 18th century; John Walker uses the spelling ar to indicate the broad A of aunt in his 1775 dictionary and reports that card is pronounced "caad" in 1791 (Labov, Ash, and Boberg 2006: 47).

Non-rhotic speakers pronounce an /r/ in red, and most pronounce it in torrid and watery, where R is followed by a vowel, but not in hard, nor in car or water when those words are said in isolation. However, in most non-rhotic accents, if a word ending in written "r" is followed closely by a word beginning with a vowel, the /r/ is pronounced—as in water ice. This phenomenon is referred to as "linking R". Many non-rhotic speakers also insert an epenthetic /r/ between vowels when the first vowel is one that can occur before syllable-final r (drawring for drawing). This so-called "intrusive R" has been stigmatized, but even speakers of so-called Received Pronunciation frequently "intrude" an epenthetic /r/ at word boundaries, especially where one or both vowels is schwa; for example the idea of it becomes the idea-r-of it, Australia and New Zealand becomes Australia-r-and New Zealand, the formerly well-known India-r-Office. The typical alternative used by RP speakers is to insert a glottal stop where an intrusive R would otherwise be placed.[1]

For non-rhotic speakers, what was historically a vowel plus /r/ is now usually realized as a long vowel. So in Received Pronunciation (RP) and many other non-rhotic accents card, fern, born are pronounced [kɑːd], [fɜːn], [bɔːn] or something similar; the pronunciations vary from accent to accent. This length may be retained in phrases, so while car pronounced in isolation is [kɑː], car owner is [kɑːɹəʊnə]. But a final schwa usually remains short, so water in isolation is [wɔːtə]. In RP and similar accents the vowels /iː/ and /uː/ (or /ʊ/), when followed by r, become diphthongs ending in schwa, so near is [nɪə] and poor is [pʊə], though these have other realizations as well, including monophthongal ones; once again, the pronunciations vary from accent to accent. The same happens to diphthongs followed by R, though these may be considered to end in /ər/ in rhotic speech, and it is the /ər/ that reduces to schwa as usual in non-rhotic speech: tire said in isolation is [taɪə] and sour is [saʊə].[2] For some speakers, some long vowels alternate with a diphthong ending in schwa, so wear may be [wɛə] but wearing [wɛːɹiŋ].

Mergers characteristic of non-rhotic accents

Some phonemic mergers are characteristic of non-rhotic accents. These usually include one item that historically contained an R (lost in the non-rhotic accent), and one that never did so. The section below lists mergers in order of approximately decreasing prevalence.

Panda–pander merger

In the terminology of Wells (1982), this consists of the merger of the lexical sets commA and lettER. It is found in all or nearly all non-rhotic accents,[3] and is even present in some accents that are in other respects rhotic, such as those of some speakers in Jamaica and the Bahamas.[3]

Homophonous pairs /ə/ /ər/ IPA Notes area airier ˈɛːriə cheetah cheater ˈtʃiːtə custody custardy ˈkʌstədi formally formerly ˈfɔːməli karma calmer ˈkɑːmə kava carver ˈkɑːvə Lisa leaser ˈliːsə Maya Meier ˈmaɪə manna manner ˈmænə manna manor ˈmænə Mona moaner ˈmoʊnə panda pander ˈpændə PETA Peter ˈpiːtə pharma farmer ˈfɑːmə Rhoda rotor ˈroʊɾə With intervocalic alveolar flapping. rota rotor ˈroʊtə schema schemer ˈskiːmə tuba tuber ˈt(j)uːbə Wanda wander ˈwɒndə Father–farther merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets PALM and START. It is found in the speech of the great majority of non-rhotic speakers, including those of England, Wales, the United States, the Caribbean, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. It may be absent in some non-rhotic speakers in the Bahamas.[3]Homophonous pairs /ɑː/ /ɑːr/ IPA Notes alms arms ˈɑːmz balmy barmy ˈbɑːmi calmer karma ˈkɑːmə Chalmers charmers ˈtʃɑːmərz fa far ˈfɑː father farther ˈfɑːðə kava carver ˈkɑːvə lava larva ˈlɑːvə ma mar ˈmɑː pa par ˈpɑː ska scar ˈskɑː spa spar ˈspɑː Pawn–porn merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets THOUGHT and NORTH. It is found in the same accents as the father–farther merger described above, but is absent from the Bahamas and Guyana.[3]Homophonous pairs /ɔː/ /ɔːr/ IPA Notes alk orc ˈɔːk auk orc ˈɔːk awe or ˈɔː awk orc ˈɔːk balk bork ˈbɔːk bawn born ˈbɔːn caulk cork ˈkɔːk cawed cord ˈkɔːd cawed chord ˈkɔːd draw drawer ˈdrɔː gnaw nor ˈnɔː laud lord ˈlɔːd lawed lord ˈlɔːd lawn Lorne ˈlɔːn pawn porn ˈpɔːn sought sort ˈsɔːt stalk stork ˈstɔːk talk torque ˈtɔːk taught tort ˈtɔːt taut tort ˈtɔːt taw tor ˈtɔː thaw Thor ˈθɔː Caught–court merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets THOUGHT and FORCE. It is found in those non-rhotic accents containing the pawn–porn merger that have also undergone the horse–hoarse merger. These include the accents of Southern England, Wales, non-rhotic New York City speakers, Trinidad and the Southern hemisphere. In such accents a three-way merger awe-or-ore/oar results.Homophonous pairs /ɔː/ /oːr/ IPA Notes awe oar ˈɔː awe ore ˈɔː bawd board ˈbɔːd bawd bored ˈbɔːd bawn borne ˈbɔːn bawn Bourne ˈbɔːn caught court ˈkɔːt caw core ˈkɔː daw door ˈdɔː flaw floor ˈflɔː fought fort ˈfɔːt gaud gored ˈɡɔːd haw whore ˈhɔː law lore ˈlɔː maw more ˈmɔː maw Moore ˈmɔː paw pore ˈpɔː paw pour ˈpɔː raw roar ˈrɔː sauce source ˈsɔːs saw soar ˈsɔː saw sore ˈsɔː sawed soared ˈsɔːd sawed sword ˈsɔːd Sean shorn ˈʃɔːn shaw shore ˈʃɔː Shawn shorn ˈʃɔːn taw tore ˈtɔː yaw yore ˈjɔː yaw your ˈjɔː Calve–carve merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets BATH and START. It is found in some non-rhotic accents with broad A in words like "bath". It is general in southern England (excluding rhotic speakers), Trinidad, the Bahamas, and the Southern hemisphere. It is a possibility for Welsh, Eastern New England, Jamaican, and Guyanese speakers.Homophonous pairs /aː/ /ɑːr/ IPA Notes aunt aren't ˈɑːnt calve carve ˈkɑːv fast farced ˈfɑːst pass parse ˈpɑːs passed parsed ˈpɑːst past parsed ˈpɑːst Paw–poor merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets THOUGHT and CURE. It is found in those non-rhotic accents containing the caught–court merger that have also undergone the pour–poor merger. Wells lists it unequivocally only for the accent of Trinidad, but it is an option for non-rhotic speakers in England, Australia and New Zealand. Such speakers have a potential four–way merger taw-tor-tore-tour.[4]Homophonous pairs /ɔː/ /ʊːr/ IPA Notes gaud gourd ˈɡɔːd haw whore ˈhɔː law lure ˈlɔː With yod dropping. maw moor ˈmɔː maw Moore ˈmɔː paw poor ˈpɔː shaw sure ˈʃɔː taw tour ˈtɔː tawny tourney ˈtɔːni yaw your ˈjɔː yaw you're ˈjɔː Batted–battered merger

This merger is present in non-rhotic accents which have undergone the weak vowel merger. Such accents include Australian, New Zealand, most South African speech, and some non-rhotic English speech.Homophonous pairs /ɪ̈/ /ər/ IPA Notes arches archers ˈɑːtʃəz batted battered ˈbætəd chatted chattered ˈtʃætəd founded foundered ˈfaʊndəd matted mattered ˈmætəd offices officers ˈɒfəsəz patted pattered ˈpætəd sauces saucers ˈsɔːsəz splendid splendo(u)red ˈsplɛndəd tended tendered ˈtɛndəd territory terror tree ˈtɛrətriː With happy tensing. Dough–door merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets GOAT and FORCE. It may be found in some southern U.S. non-rhotic speech, some speakers of African American Vernacular English, some speakers in Guyana and some Welsh speech.[3]Homophonous pairs /oʊ/ /oʊr/ IPA Notes beau boar ˈboʊ beau bore ˈboʊ bode board ˈboʊd bode bored ˈboʊd bone borne ˈboʊn bone Bourne ˈboʊn bow boar ˈboʊ bow bore ˈboʊ chose chores ˈtʃoʊz coat court ˈkoʊt code cored ˈkoʊd doe door ˈdoʊ does doors ˈdoʊz dough door ˈdoʊ doze doors ˈdoʊz floe floor ˈfloʊ flow floor ˈfloʊ foe fore ˈfoʊ foe four ˈfoʊ go gore ˈɡoʊ goad gored ˈɡoʊd hoe whore ˈhoʊ hoes whores ˈhoʊz hose whores ˈhoʊz lo lore ˈloʊ low lore ˈloʊ moan mourn ˈmoʊn Moe Moore ˈmoʊ Moe more ˈmoʊ mow Moore ˈmoʊ mow more ˈmoʊ mown mourn ˈmoʊn O oar ˈoʊ O ore ˈoʊ ode oared ˈoʊd oh oar ˈoʊ oh ore ˈoʊ owe oar ˈoʊ owe ore ˈoʊ owed oared ˈoʊd Po pore ˈpoʊ Po pour ˈpoʊ Poe pore ˈpoʊ Poe pour ˈpoʊ poach porch ˈpoʊtʃ poke pork ˈpoʊk pose pores ˈpoʊz pose pours ˈpoʊz road roared ˈroʊd rode roared ˈroʊd roe roar ˈroʊ roes roars ˈroʊz rose roars ˈroʊz row roar ˈroʊ rows roars ˈroʊz sew soar ˈsoʊ sew sore ˈsoʊ shew shore ˈʃoʊ shone shorn ˈʃoʊn show shore ˈʃoʊ shown shorn ˈʃoʊn snow snore ˈsnoʊ so soar ˈsoʊ so sore ˈsoʊ sow soar ˈsoʊ sow sore ˈsoʊ stow store ˈstoʊ toe tore ˈtoʊ tone torn ˈtoʊn tow tore ˈtoʊ woe wore ˈwoʊ whoa wore ˈwoʊ With wine–whine merger. yo yore ˈjoʊ yo your ˈjoʊ Show–sure merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets GOAT and CURE. It may be present in those speakers who have both the dough–door merger described above, and also the pour–poor merger. These include some southern U.S. non-rhotic speakers, some speakers of African American Vernacular English, and some speakers in Guyana.[3]Homophonous pairs /oʊ/ /ʊːr/ IPA Notes beau boor ˈboʊ bow boor ˈboʊ goad goured ˈɡoʊd hoe whore ˈhoʊ lo lure ˈloʊ With yod dropping. low lure ˈloʊ With yod dropping. Moe moor ˈmoʊ Moe Moore ˈmoʊ mow moor ˈmoʊ mow Moore ˈmoʊ Po poor ˈpoʊ Poe poor ˈpoʊ shew sure ˈʃoʊ show sure ˈʃoʊ toe tour ˈtoʊ tow tour ˈtoʊ yo your ˈjoʊ yo you're ˈjoʊ Often–orphan merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets CLOTH and NORTH. It may be present in old-fashioned Eastern New England accents,[5] New York City speakers[6] and also in some speakers in Jamaica and Guyana. The merger was also until recently present in the dialects of southern England, including Received Pronunciation — specifically, the phonemic merger of the words often and orphan was a running gag in the Gilbert and Sullivan musical, The Pirates of Penzance.Homophonous pairs /ɒː/ /ɔːr/ IPA Notes hoss horse ˈhɔːs The word hoss actually arose as a dialectal spelling of horse with this merger. moss Morse ˈmɔːs off Orff ˈɔːf often orphan ˈɔːfən God–guard merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets LOT and START. It may be present in non-rhotic accents that have undergone the father–bother merger. These may include some New York accents,[7] some southern U.S. accents,[8] and African American Vernacular English.[9]Homophonous pairs /ɑ/ /ɑr/ IPA Notes bob barb ˈbɑb bock bark ˈbɑk bocks barks ˈbɑks bod bard ˈbɑd bod barred ˈbɑd bot Bart ˈbɑt box barks ˈbɑks clock Clark ˈklɑk cob carb ˈkɑb cod card ˈkɑd cop carp ˈkɑp cot cart ˈkɑt dock dark ˈdɑk dolling darling ˈdɑlɪŋ don darn ˈdɑn dot dart ˈdɑt god guard ˈɡɑd hock hark ˈhɑk hop harp ˈhɑp hot hart ˈhɑt hot heart ˈhɑt hottie hardy ˈhɑɾi With intervocalic alveolar flapping. hottie hearty ˈhɑti hough hark ˈhɑk hovered Harvard ˈhɑvəd knock narc ˈnɑk knocks narcs ˈnɑks Knox narcs ˈnɑk lock lark ˈlɑk lodge large ˈlɑdʒ mock mark ˈmɑk mocks marks ˈmɑks mocks Marx ˈmɑks mod marred ˈmɑd mosh marsh ˈmɑʃ ox arks ˈɑks pock park ˈpɑk pocks parks ˈpɑks pot part ˈpɑt potty party ˈpɑti pox parks ˈpɑks shod shard ˈʃɑd shock shark ˈʃɑk shop sharp ˈʃɑp sock Sark ˈsɑk sod Sard ˈsɑd Spock spark ˈspɑk spotter Sparta ˈspɑtə stock stark ˈstɑk Todd tarred ˈtɑd top tarp ˈtɑp tot tart ˈtɑt yon yarn ˈjɑn Shot–short merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets LOT and NORTH. It may be present in some Eastern New England accents.[10][11]Homophonous pairs /ɒ/ /ɒr/ IPA Notes cock cork ˈkɒk cod chord ˈkɒd cod cord ˈkɒd con corn ˈkɒn odder order ˈɒdə otter order ˈɒɾə With intervocalic alveolar flapping. shoddy shorty ˈʃɒɾi With intervocalic alveolar flapping. shot short ˈʃɒt snot snort ˈsnɒt solder sorter ˈsɒɾə With intervocalic alveolar flapping. stock stork ˈstɒk swat swart ˈswɒt tock torque ˈtɒk wabble warble ˈwɒbəl wad ward ˈwɒd wad warred ˈwɒd wan warn ˈwɒn watt wart ˈwɒt what wart ˈwɒt With wine–whine merger. whop warp ˈwɒp With wine–whine merger. wobble warble ˈwɒbəl Bud–bird merger

[citation needed] A merger of /ɜː(r)/ and /ʌ/ occurring for some speakers of Jamaican English making bud and bird homophones as /bʌd/.[12] The conversion of /ɜː/ to [ʌ] or [ə] is also found in places scattered around England and Scotland. Some speakers, mostly rural, in the area from London to Norfolk exhibit this conversion, mainly before voiceless fricatives. This gives pronunciation like first [fʌst] and worse [wʌs]. The word cuss appears to derive from the application of this sound change to the word curse. Similarly, lurve is coined from love.Homophonous pairs /ʌ/ /ɜːr/ IPA Notes blood blurred ˈblʌd buck Burke ˈbʌk bud bird ˈbʌd bug burg ˈbʌɡ bugger burger ˈbʌɡə bummer Burma ˈbʌmə bun Bern ˈbʌn bun burn ˈbʌn bunt burnt ˈbʌnt bussed burst ˈbʌst bust burst ˈbʌst but Bert ˈbʌt but Burt ˈbʌt butt Bert ˈbʌt butt Burt ˈbʌt button Burton ˈbʌtən chuck chirk ˈtʃʌk cluck clerk ˈklʌk cub curb ˈkʌb cub kerb ˈkʌb cud curd ˈkʌd cull curl ˈkʌl cunning kerning ˈkʌnɪŋ cuss curse ˈkʌs cut curt ˈkʌt doth dearth ˈdʌθ duck dirk ˈdʌk fun fern ˈfʌn fussed first ˈfʌst fuzz furs ˈfʌz gull girl ˈɡʌl gutter girder ˈɡʌɾə With intervocalic alveolar flapping. hub herb ˈhʌb huddle hurdle ˈhʌdəl hull hurl ˈhʌl hum herm ˈhʌm hush Hirsch ˈhʌʃ hut hurt ˈhʌt love lurve ˈlʌv luck lurk ˈlʌk muck mirk ˈmʌk muck murk ˈmʌk mull merl ˈmʌl mutter murder ˈmʌɾə With intervocalic alveolar flapping. puck perk ˈpʌk pup perp ˈpʌp pus purse ˈpʌs putt pert ˈpʌt shuck shirk ˈʃʌk spun spurn ˈspʌn stud stirred ˈstʌd such search ˈsʌtʃ suck cirque ˈsʌk suckle circle ˈsʌkəl suffer surfer ˈsʌfə sully surly ˈsʌli Sutton certain ˈsʌtn̩ With n-syllabification. thud third ˈθʌd ton(ne) tern ˈtʌn ton(ne) turn ˈtʌn tough turf ˈtʌf tuck Turk ˈtʌk us Erse ˈʌs Oil–earl merger

In Wells' terminology, this consists of the merger of the lexical sets CHOICE and NURSE preconsonantally. It was present in older New York accents, but became stigmatized and is sharply recessive in those born since the Second World War.[13] This merger is known for the word soitanly, used often by the Three Stooges comedian Curly Howard as a variant of certainly, in comedy shorts of the 1930s and '40s.Homophonous pairs Other mergers

In some accents, syllabification may interact with rhoticity, resulting in homophones where non-rhotic accents have centering diphthongs. Possibilities include Korea–career,[14] Shi'a–sheer, and Maia–mire,[15] while skua may be identical with the second syllable of obscure.[16]

Distribution

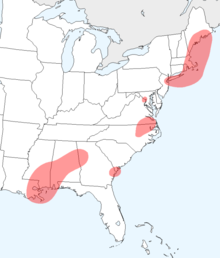

The red areas are those where Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006:48) found some non-rhotic pronunciation among some whites in major cities in the United States. AAVE-influenced non-rhotic pronunciations may be found among African-Americans throughout the country.

The red areas are those where Labov, Ash, and Boberg (2006:48) found some non-rhotic pronunciation among some whites in major cities in the United States. AAVE-influenced non-rhotic pronunciations may be found among African-Americans throughout the country.

Examples of rhotic accents are: Scottish English, Mid Ulster English, Canadian English and most varieties of American English. Non-rhotic accents include most accents of England, New Zealand, Australia, South Africa.

Most speakers of most of North American English are rhotic, as are speakers from Barbados, Scotland and most of Ireland.

In England, rhotic accents are found in the West Country (south and west of a line from near Shrewsbury to around Portsmouth), the Corby area, most of Lancashire (north and east of the center of Manchester), some parts of Yorkshire and Lincolnshire and in the areas that border Scotland. The prestige form, however, exerts a steady pressure towards non-rhoticity. Thus the urban speech of Bristol or Southampton is more accurately described as variably rhotic, the degree of rhoticity being reduced as one moves up the class and formality scales.[18]

Most speakers of Indian English have a rhotic accent.,[19] while Pakistani English can be either rhotic or non rhotic.[20] Other areas with rhotic accents include Otago and Southland in the far south of New Zealand's South Island, where a Scottish influence is apparent.

Areas with non-rhotic accents include Australia, most of the Caribbean, most of England (including Received Pronunciation speakers), most of New Zealand, Wales, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

Canada is entirely rhotic except for small isolated areas in southwestern New Brunswick, parts of Newfoundland, and Lunenburg and Shelburne Counties, Nova Scotia.

In the United States, much of the South was once non-rhotic, but in recent decades non-rhotic speech has declined. Today, non-rhoticity in Southern American English is found primarily among older speakers, and only in some areas such as central and southern Alabama, Savannah, Georgia, and Norfolk, Virginia.[21] Parts of New England, especially Boston, are non-rhotic as well as New York City and surrounding areas. African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is largely non-rhotic.

In some non-rhotic Southern American and AAVE accents, there is no linking r, that is, /r/ at the end of a word is deleted even when the following word starts with a vowel, so that "Mister Adams" is pronounced [mɪstə(ʔ)ˈædəmz].[22] In a few such accents, intervocalic /r/ is deleted before an unstressed syllable even within a word when the following syllable begins with a vowel. In such accents, pronunciations like [kæəˈlaːnə] for Carolina [bɛːˈʌp] for "bear up" are heard.[23] This pronunciation also occurs in AAVE.[24]

The English spoken in Asia, India,[19] and the Philippines is predominantly rhotic. In the case of the Philippines, this may be explained because the English that is spoken there is heavily influenced by the American dialect. In addition, many East Asians (in China, Japan, Korea, and Taiwan) who have a good command of English generally have rhotic accents because of the influence of American English. This excludes Hong Kong, whose RP English dialect is a result of its almost 150-year-history as a British Crown colony (later British dependent territory).

Other Asian regions with non-rhotic English are Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei. Spoken English in Myanmar is non-rhotic, but there are a number of English speakers with a rhotic or partially rhotic pronunciation.

Other languages

Other Germanic languages

The rhotic consonant is dropped or vocalized under similar conditions in other Germanic languages, notably German, Danish and some dialects of southern Sweden (possibly because of its Danish history). In most varieties of German, /r/ in the syllable coda is frequently realized as a vowel or a semivowel, [ɐ] or [ɐ̯], especially in the unstressed ending -er and after long vowels: for example sehr [zeːɐ̯], besser [ˈbɛsɐ]. Similarly, Danish /r/ after a vowel is, unless followed by a stressed vowel, either pronounced [ɐ̯] (mor "mother" [moɐ̯], næring "nourishment" [ˈnɛɐ̯eŋ]) or merged with the preceding vowel while usually influencing its vowel quality (/a(ː)r/ and /ɔːr/ or /ɔr/ are realised as long vowels [aː] and [ɒː], and /ər/, /rə/ and /rər/ are all pronounced [ɐ]) (løber "runner" [ˈløːb̥ɐ], Søren Kierkegaard (personal name) [ˌsœːɐn ˈkʰiɐ̯ɡ̊əˌɡ̊ɒːˀ]).

Catalan

In Catalan, word final /r/ is lost in coda position not only in suffixes on nouns and adjectives denoting the masculine singular (written as -r) but also in the "-ar, -er, -ir" suffixes of infinitives; e.g. forner [furˈne] "(male) baker", fer [ˈfe] "to do", lluir [ʎuˈi] "to shine, to look good". However, rhotics are "recovered" when followed by the feminine suffix -a [ə], and when infinitives have single or multiple enclitic pronouns (notice the two rhotics are neutralized in the coda, with a tap [ɾ] occurring between vowels, and a trill [r] elsewhere); e.g. fornera [furˈneɾə] "(female) baker", fer-lo [ˈferɫu] "to do it (masc.)", fer-ho [ˈfeɾu] "to do it/that/so", lluir-se [ʎuˈir.sə] "to excel, to show off".

Chinese

In Mandarin, many words are pronounced with the coda [ɻ], originally a diminutive ending. But this happens only in some areas, mainly in the Northern region, notably including Beijing; in other areas it tends to be omitted. But in words with an inherent coda, such as [ɑ̂ɻ] 二 "two", the [ɻ] is pronounced.

Khmer

In standard Khmer the final /r/ is unpronounced. If an /r/ occurs as the second consonant of a cluster in a minor syllable, it is also unpronounced. The informal speech of Phnom Penh has gone a step further, dropping the /r/ when it occurs as the second consonant of a cluster in a major syllable while leaving behind a dipping tone. When an /r/ occurs as the initial of a syllable, it becomes uvular in contrasts to the trilled /r/ in standard speech.

Portuguese

In some dialects of Brazilian Portuguese, /r/ is unpronounced or aspirated. This occurs most frequently with verbs in the infinitive, which is always indicated by a word-final /r/. In some states, however, it happens mostly with any /r/ when preceding a consonant.

Spanish

Among the Spanish dialects, Andalusian Spanish, Caribbean Spanish (descended from and still closely related to Andalusian and Canary Island Spanish), and the Argentinian dialect spoken in the Tucumán province have an unpronounced word-final /r/, especially in infinitives which mirrors the situation in some dialects of Brazilian Portuguese. However, in the Caribbean forms, word-final /r/ in infinitives and non-infinitives is often in free variation with word-final /l/ and may relax to the point of being articulated as /i/.

Uyghur

Among the Turkic languages, Uyghur displays more or less the same feature, as syllable-final /r/ is dropped, while the preceding vowel is lengthened: for example Uyghurlar [ʔʊɪˈʁʊːlaː] ‘Uyghurs’. The /r/ may, however, sometimes be pronounced in unusually "careful" or "pedantic" speech; in such cases, it is often mistakenly inserted after long vowels even when there is no phonemic /r/ there.

Yaqui

Similarly in Yaqui, an indigenous language of northern Mexico, intervocalic or syllable-final /r/ is often dropped with lengthening of the previous vowel: pariseo becomes [paːˈseo], sewaro becomes [sewajo].

Effect on spelling

Spellings based on non-rhotic pronunciation of dialectal or foreign words can result in mispronunciations if read by rhotic speakers. In addition to juggernaut mentioned above, the following are found:

- "Er", to indicate a filled pause, as a British spelling of what Americans would render "uh".

- The Korean family name Bak/Pak usually written "Park" in English.

- The game Parcheesi.

- British English slang words:

- "char" for "cha" from the Mandarin Chinese pronunciation of 茶 (= "tea" (the drink))

- "nark" (= "informer") from Romany "nāk" (= "nose").

- In Rudyard Kipling's books:

- "dorg" instead of "dawg" for a drawled pronunciation of "dog".

- Hindu god name Kama misspelled as "Karma" (which refers to a concept in several Asian religions, not a god).

- Hindustani कागज़ "kāgaz" (= "paper") spelled as "kargaz".

- "Burma" and "Myanmar" for Burmese [bəmà] and [mjàmmà].

- Transliteration of Cantonese words and names, such as char siu (叉燒, Jyutping: caa1 siu1) and Wong Kar-wai (王家衛, Jyutping: Wong4 Gaa1wai6)

- The spelling of "schoolmarm" for "school ma'am".

See also

References

- ^ Wells, Accents of English, 1:224.

- ^ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ a b c d e f Wells (1982)

- ^ Wells, p. 287

- ^ Wells, p. 524

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 503

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 504

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 544

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 577

- ^ Wells, p. 520

- ^ Dillard, Joey Lee (1980). Perspectives on American English. The Hague; New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 53. ISBN 9027933677. http://books.google.com/books?id=6zPgjduXBcQC.

- ^ Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22919-7 (vol. 1), ISBN 0-521-24224-X (vol. 2), ISBN 0-521-24225-8 (vol. 3)., pp. 136–37, 203–6, 234, 245–47, 339–40, 400, 419, 443, 576

- ^ Wells (1982), pp. 508-509

- ^ Wells (1982), p. 225

- ^ Upton, Clive; Eben Upton (2004). Oxford rhyming dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0192801155.

- ^ Upton, Clive; Eben Upton (2004). Oxford rhyming dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 0192801155.

- ^ Wakelyn, Martin: "Rural dialects in England", in: Trudgill, Peter (1984): Language in the British Isles, p.77

- ^ Trudgill, Peter (1984). Language in the British Isles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521284090, 9780521284097.

- ^ a b Wells, J. C. (1982). Accents of English 3: Beyond the British Isles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 629. ISBN 0521285410.

- ^ http://www.reference-global.com/doi/abs/10.1515/9783110208429.1.244

- ^ Labov, Ash, and Boberg, 2006: pp. 47–48.

- ^ Gick, Bryan. 1999. A gesture-based account of intrusive consonants in English. Phonology 16: 1, pp. 29–54. (pdf). Accessed November 12, 2010.

- ^ Harris 2006: pp. 2–5.

- ^ Pollock et al., 1998.

Bibliography

- Harris, John. 2006. "Wide-domain r-effects in English" (pdf). Accessed March 24, 2007.

- Labov, William, Sharon Ash, and Charles Boberg. 2006. The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- Pollock, K., et al. 1998. "Phonological Features of African American Vernacular English (AAVE)". Accessed March 24, 2007.

- Wells, J. C. Accents of English. 3 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1982.

External links

- Chapter 7 of the Atlas of North American English by William Labov et al., dealing with rhotic and non-rhotic accents in the U.S. (PDF file)

- Rhotic vs non-rhotic, intrusive "r" from the alt.usage.english newsgroup's FAQ

- Rhotic or non-rhotic English?, Pétur Knútsson, University of Iceland

- 'Hover & Hear' accents of English from around the world, both rhotic and non-rhotic.

The Letter "R" General The letter R · Rhotic consonants (R-like sounds) · Rhotic and non-rhotic accents · R-colored vowels · Guttural R · Linking and intrusive RPronunciations Alveolar trill [r] · Alveolar approximant [ɹ] · Alveolar tap [ɾ] · Alveolar lateral flap [ɺ] · Retroflex approximant [ɻ] · Retroflex flap [ɽ] · Retroflex trill [ɽ͡r] · Uvular trill [ʀ] · Voiced uvular fricative [ʁ] · Labialized [ʋ]Variations Categories:- English phonology

- English dialects

- Splits and mergers in English phonology

- American English

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.