- English-language vowel changes before historic r

-

In the phonological history of the English language, vowels followed (or formerly followed) by the phoneme /r/ have undergone a number of phonological changes. In recent centuries, most or all of these changes have involved merging of vowel distinctions.

Contents

Overview

In most North American accents, for example, although there are ten or eleven stressed monophthongs, only five or six vowel contrasts are possible before a following /r/ in the same syllable (peer, pear, purr, pore, par, poor). Often, more contrasts exist when the /r/ is not in the same syllable; in some American dialects and in most native English dialects outside North America, for example, mirror and nearer do not rhyme, and some or all of marry, merry and Mary are pronounced distinctly. (In North America, these distinctions are most likely to occur in New York City, Philadelphia, Eastern New England (including Boston), and in conservative Southern accents.) In nearly all dialects, however, the number of contrasts in this position is reduced, and the tendency is towards further reduction. The difference in how these reductions have been manifested represents one of the greatest sources of cross-dialect variation.

Non-rhotic accents often show mergers in the same positions as rhotic accents do, even though there is often no /r/ phoneme present. This results partly from mergers that occurred before the /r/ was lost, and partly from later mergers of the centering diphthongs and long vowels that resulted from the loss of /r/.

The American phenomenon is one of tense–lax neutralization,[2][3] where the normal English distinction between tense and lax vowels is eliminated.

In some cases, the quality of a vowel before /r/ is different from the quality of the vowel elsewhere. For example, in American English the quality of the vowel in more typically does not occur except before /r/, and is somewhere in between the vowels of maw and mow. (It is similar to the vowel of the latter word, but without the glide.)

Different mergers occur in different dialects. Among United States accents, the Boston and New York accents have the least degree of pre-rhotic merging. Some have observed that rhotic North American accents are more likely to have such merging than non-rhotic accents, but this cannot be said of rhotic British accents like Scottish English, which is firmly rhotic and yet many varieties have all the same vowel contrasts before /r/ as before any other consonant.

Mergers before intervocalic r

Mary–marry–merry merger

One of the best-known pre-rhotic mergers is known as the Mary–marry–merry merger,[4] which consists of the mergers before intervocalic /r/ of /æ/ and /ɛ/ with historical /eɪ/.[5] This merger is quite widespread in North America.[sample 1] A merger of Mary and merry, while keeping marry distinct, is found in the South and as far north as Baltimore, Maryland, and Wilmington, Delaware; it is also found among Anglophones in Montreal.[6] In the Philadelphia accent the three-way contrast is preserved, but merry tends to be merged with Murray; likewise ferry can be a homophone of furry. (See furry–ferry merger below.) The three are kept distinct outside of North America, as well as in the accents of Philadelphia, New York City, Boston, and Providence, Rhode Island.[7][sample 2] In accents that do not have the merger, Mary has the a sound of mare, marry has the a sound of mat and merry has the e sound of met. There is plenty of variance in the distribution of the merger, with expatriate communities of these speakers being formed all over the country.

Homophonous pairs /eər/ /ær/ /ɛr/ IPA Notes Aaron1 Aaron2 Erin ˈɛrən With weak vowel merger. - Barry berry ˈbɛri - Barry bury ˈbɛri Cary1 Carrie Kerry ˈkɛri Cary1 carry Kerry ˈkɛri Cary1 Cary2 Kerry ˈkɛri dairy - Derry ˈdɛri fairy - ferry ˈfɛri - Farrell feral ˈfɛrəl With weak vowel merger before /l/. Gary1 Gary2 - ˈɡɛri hairy Harry - ˈhɛri Mary marry merry ˈmɛri - parish perish ˈpɛrɪʃ - parry Perry ˈpɛri scary - skerry ˈskɛri tarry - Terry ˈtɛri The verb tarry, not the adjective. vary - very ˈvɛri Mirror–nearer merger

Another widespread merger is that of /ɪ/ with /iː/ before intervocalic /r/. For speakers with this merger, mirror and nearer rhyme, and Sirius is homophonous with serious. North Americans who do not merge these vowels often speak the more conservative northeastern or southern accents.

Hurry–furry merger

The merger of /ʌ/ before intervocalic /r/ with /ɝ/ is also widespread in American English apart from the Northeast and the South of the US.[8] Speakers with this merger pronounce hurry to rhyme with furry. In accents that lack the fern–fir–fur merger, hurry and furry rhyme, but they rhyme because they never split in those accents to begin with. Other pairs such as stir it versus turret are split in all accents outside North America.

Furry–ferry merger

The merger of /ɛ/ and /ʌ/ before /r/ (both neutralized with syllabic r) is common in the Philadelphia accent.[9] This accent does not usually have the marry–merry merger. That is, "short a" /æ/ as in marry is a distinct unmerged class before /r/. Thus, merry and Murray are pronounced the same, but marry is distinct from this pair.

Homophonous pairs /ɜr/ /ɛr/ IPA Notes curry Kerry ˈkɜri furry ferry ˈfɜri Murray merry ˈmɜri purry Perry ˈpɜri scurry skerry ˈskɜri Historic "short o" before intervocalic r

Words that have /ɒ/ before intervocalic /r/ in RP are treated differently in different varieties of North American English. As shown in the table below, in Canadian English, all of these are pronounced with [-ɔr-], as in cord (and thus merge with historic prevocalic /ɔːr/ in words like glory because of the horse–hoarse merger). In the accents of New York, Philadelphia, and the Carolinas, these words are pronounced among some with [-ɑr-], as in card (and thus merge with historic prevocalic /ɑːr/ in words like starry). In the Boston accent these words are pronounced with [-ɒr-], similar to in RP. Most of the rest of the United States (marked "Gen.Am." in the table), however, has a mixed system: while the majority of words are pronounced as in Canada, the four words in the right-hand column are typically pronounced with [-ɑr-].[10]

RP and Boston /ɒr/ Canada /ɔr/ NYC, Philadelphia, and the Carolinas /ɑr/ Gen.Am. /ɔr/ Gen.Am. /ɑr/ foreign

Oregon

origin

Florida

forest

horrible

quarrel

warren

warrantyborrow

sorry

sorrow

tomorrowEven in the Northeastern accents without the split (Boston, New York, Philadelphia), some of the words in the original short-o class often show influence from other American dialects and end up with [-ɔr-] anyway. For instance, some speakers from the Northeast may, for example, pronounce Florida, orange, and horrible with [-ɑr-], but foreign and origin with [-ɔr-]. Exactly which words are affected by this differs from dialect to dialect and occasionally from speaker to speaker, an example of sound change by lexical diffusion.

Mergers and splits before historic coda r

Cheer–chair merger

The cheer–chair merger is the merger of the Early Modern English sequences /iːr/ and /ɛːr/ (and the /eːr/ between them), which is found in some accents of modern English. Some speakers in New York City and New Zealand merge them in favor of the CHEER vowel, while some speakers in East Anglia and South Carolina merge them in favor of the CHAIR vowel.[11] The merger is widespread in the Anglophone Caribbean.

Homophonous pairs /ɪə(r)/ /eə(r)/ IPA (V=ɪ~e) beard Baird ˈbVə(r)d beer bare ˈbVə(r) beer bear ˈbVə(r) cheer chair ˈtʃVə(r) clear Claire ˈklVə(r) dear dare ˈdVə(r) deer dare ˈdVə(r) ear air ˈVə(r) ear ere ˈVə(r) ear heir ˈVə(r) fear fair ˈfVə(r) fear fare ˈfVə(r) fleer flair ˈflVə(r) fleer flare ˈflVə(r) hear hair ˈhVə(r) hear hare ˈhVə(r) here hair ˈhVə(r) here hare ˈhVə(r) leer lair ˈlVə(r) leered laird ˈlVə(r)d mere mare ˈmVə(r) near nare ˈnVə(r) peer pair ˈpVə(r) peer pare ˈpVə(r) peer pear ˈpVə(r) pier pair ˈpVə(r) pier pare ˈpVə(r) pier pear ˈpVə(r) rear rare ˈrVə(r) shear share ˈʃVə(r) sheer share ˈʃVə(r) sneer snare ˈsnVə(r) spear spare ˈspVə(r) tear (weep) tare ˈtVə(r) tear (weep) tear (rip) ˈtVə(r) tier tare ˈtVə(r) tier tear (rip) ˈtVə(r) weary wary ˈwVəri weir ware ˈwVə(r) weir wear ˈwVə(r) we're ware ˈwVə(r) we're wear ˈwVə(r) Fern–fir–fur merger

The fern–fir–fur merger is the merger of the Middle English vowels /ɛ, ɪ, ʊ/ into [ɜ] when historically followed by /r/ in the coda of the syllable. As a result of this merger, the vowels in fern, fir and fur are the same in almost all accents of English; the exceptions are Scottish English and some varieties of Hiberno-English.

In non-merging accents:

- The fur vowel is also used in:

- The spelling ‹or› in words like attorney, word, work, world, worm, worse, worship, worst, wort, worth and worthy. Compare the surviving /ʌ.r/ (barring the Hurry–furry merger) in words like worry.

- The spelling ‹our› in words like adjourn, courteous, courtesy, journal, journey, scourge and sojourn. Compare the surviving /ʌ.r/ (barring the Hurry–furry merger) in words like courage, flourish and nourish.

- The ‹ere› spelling in the word were (as conjugated form of to be) is observed to be the fern vowel in Scottish English and in Hiberno-English.

- But the two accents disagree on how to pronounce the ‹ear› spelling (representing historical */er/ no longer independently distinguished) in words like dearth, earl, early, earn, earnest, Earp, earth, heard, hearse, Hearst, learn, learnt, pearl, rehearse, search and yearn:

- In Scottish English, these use the fern vowel. This makes heard and herd rhyme.

- In Hiberno-English, these use the fir vowel. This makes heard and herd non-rhyming.

Homophonous pairs /ɛr/ */er/ /ɪr/ /ʌr/ IPA Notes Bern - - burn ˈbɜː(r)n Bert - - Burt ˈbɜː(r)t berth - birth - ˈbɜː(r)θ - earn - urn ˈɜː(r)n Ernest earnest - - ˈɜː(r)nɪst herd heard - - ˈhɜː(r)d - - fir fur ˈfɜː(r) kerb - - curb ˈkɜː(r)b - - mirk murk ˈmɜː(r)k Perl pearl - - ˈpɜː(r)l tern - - turn ˈtɜː(r)n - whirled - world ˈwɜː(r)ld With wine–whine merger. Square–nurse merger

The square–nurse merger is a merger of /ɜː(r)/ with /eə(r)/ that occurs in some accents (for example Liverpool, Dublin, and Belfast).[12]

Homophonous pairs /eə(r)/ /ɜː(r)/ IPA air err ˈɜː(r) Baird bird ˈbɜː(r)d Baird burd ˈbɜː(r)d Baird burred ˈbɜː(r)d bare burr ˈbɜː(r)d bared bird ˈbɜː(r)d bared burd ˈbɜː(r)d bared burred ˈbɜː(r)d bear burr ˈbɜː(r) Blair blur ˈblɜː(r) blare blur ˈblɜː(r) cairn kern ˈkɜː(r)n care cur ˈkɜː(r) care curr ˈkɜː(r) cared curd ˈkɜː(r)d cared curred ˈkɜː(r)d cared Kurd ˈkɜː(r)d chair chirr ˈtʃɜː(r) ere err ˈɜː(r) fair fir ˈfɜː(r) fair fur ˈfɜː(r) fare fir ˈfɜː(r) fare fur ˈfɜː(r) hair her ˈhɜː(r) haired heard ˈhɜː(r)d haired herd ˈhɜː(r)d hare her ˈhɜː(r) heir err ˈɜː(r) pair per ˈpɜː(r) pair purr ˈpɜː(r) pare per ˈpɜː(r) pare purr ˈpɜː(r) pear per ˈpɜː(r) pear purr ˈpɜː(r) share sure ˈʃɜː(r) With cure–fir merger. spare spur ˈspɜː(r) stair stir ˈstɜː(r) stare stir ˈstɜː(r) ware whir With wine–whine merger. ˈwɜː(r) ware were ˈwɜː(r) wear whir With wine–whine merger. ˈwɜː(r) wear were ˈwɜː(r) where were With wine–whine merger. ˈwɜː(r) where whir ˈhwɜː(r) It is possible that the merger is found in at least some varieties of African American Vernacular English. In Chingy's song "Right Thurr", the merger is heard at the beginning of the song, but he goes on to use standard pronunciation for the rest of the song.[sample 3] In the absence of phonological research in St. Louis, Missouri (Chingy's hometown), it is impossible to know whether there is a genuine phonemic merger here or not.

Labov (1994) also reports such a merger in some western parts of the United States 'with a high degree of r constriction.'

Stir–steer merger

In older varieties of Southern American English and the West Country dialects of English English, words like ear, here, and beard are pronounced /jɝ/, /hjɝ/, /bjɝd/,[13] meaning that there is no complete merger: word pairs like beer and burr are still distinguished as /bjɝ/ vs. /bɝ/. However, if the syllable begins with a consonant cluster (e.g. queer) or a palato-alveolar consonant (e.g. cheer), then there is no /j/ sound: /kwɝ/, /tʃɝ/. It is thus possible that pairs like steer-stir are merged in some accents as /stɝ/, although this is not explicitly reported in the literature.

There is evidence that African American Vernacular English speakers in Memphis, Tennessee, merge both /ɪr/ and /ɛr/ with /ɝ/, so that here and hair are both homophonous with the strong pronunciation of her.[14]

Tower–tire, tower–tar and tire–tar mergers

The tower–tire and tower–tar mergers are vowel mergers in some accents of Southern British English (including many types of RP, as well as the accent of Norwich) that causes the triphthong /aʊə/ of tower to merge either with the /aɪə/ of tire (both surfacing as diphthongal /ɑə/) or with the /ɑː/ of tar. Some speakers merge all three sounds, so that tower, tire, and tar are all homophonous as /tɑː/.[15]

The tire–tar merger, with tower kept distinct, is found in some Midland and Southern U.S. accents.[16]

Homophonous pairs /aʊə(r)/ /aɪə(r)/ /ɑː(r)/ IPA Bauer buyer bar ˈbɑː(r) coward - card ˈkɑː(r)d cower - car ˈkɑː(r) cowered - card ˈkɑː(r)d - fire far ˈfɑː(r) flour flyer - ˈflɑː(r) flower flyer - ˈflɑː(r) hour ire are ˈɑː(r) Howard hired hard ˈhɑː(r)d - mire mar ˈmɑː(r) our ire are ˈɑː(r) power pyre par ˈpɑː(r) sour sire - ˈsɑː(r) scour - scar ˈskɑː(r) shower shire - ˈʃɑː(r) showered - shard ˈʃɑː(r)d - spire spar ˈspɑː(r) tower tire tar ˈtɑː(r) tower tyre tar ˈtɑː(r) Cure–fir merger

In East Anglia a merger with the [ɜː] of shirt is common, especially after palatal and palatoalveolar consonants, so that sure is often pronounced [ʃɜː]; yod dropping may apply as well, yielding pronunciations such as [pɜː] for pure. Similarly in American English sure is often pronounced /ʃɝ/.[17] Other American pronunciations showing this merger include /pjɝ/ pure, /ˈkjɝiəs/ curious, /ˈbjɝo/ bureau, /ˈmjɝəl/ mural.[18]

Homophonous pairs /jʊə(r)/ /ɜː(r)/ IPA Notes cure cur ˈkɜː(r) cure curr ˈkɜː(r) cured curd ˈkɜː(r)d cured curred ˈkɜː(r)d fury furry ˈfɜːri pure per ˈpɜː(r) pure purr ˈpɜː(r) Pour–poor merger

In Modern English dialects, the reflexes of Early Modern English /uːr/ and /iur/ are highly susceptible to phonemic merger with other vowels. Words belonging to this class are most commonly spelled with oor, our, ure, or eur; examples include poor, tour, cure, Europe. Wells refers to this class as the CURE words, after the keyword of the lexical set to which he assigns them.

In traditional Received Pronunciation and General American, CURE words are pronounced with RP /ʊə/ (/ʊər/ before a vowel) and GenAm /ʊr/. But these pronunciations are being replaced by other pronunciations in many English accents.

In English English it is now common to pronounce CURE words with /ɔː/, so that moor is often pronounced /mɔː/, tour /tɔː/, poor /pɔː/.[19] The traditional form is much more common in the northern counties of England. A similar merger is encountered in many varieties of American English, where the pronunciations [oə] or [or]~[ɔr] (depending on whether the accent is rhotic or non-rhotic) prevail.[20][21]

Homophonous pairs /ʊə/ /ɔː/ IPA Notes boor boar ˈbɔː(r) With horse–hoarse merger. boor bore ˈbɔː(r) With horse–hoarse merger. gourd gaud ˈɡɔːd Non-rhotic. gourd gored ˈɡɔː(r)d With horse–hoarse merger. lure law ˈlɔː Non-rhotic with yod dropping. lure lore ˈlɔː(r) With horse–hoarse merger and yod dropping. lured laud ˈlɔːd Non-rhotic with yod dropping. lured lawed ˈlɔːd Non-rhotic with yod dropping. lured lord ˈlɔː(r)d With yod dropping. moor maw ˈmɔː Non-rhotic. moor more ˈmɔː(r) With horse–hoarse merger. poor paw ˈpɔː Non-rhotic. poor pore ˈpɔː(r) With horse–hoarse merger. poor pour ˈpɔː(r) With horse–hoarse merger. sure shaw ˈʃɔː Non-rhotic. sure shore ˈʃɔː(r) With horse–hoarse merger. tour taw ˈtɔː Non-rhotic. tour tor ˈtɔː(r) tour tore ˈtɔː(r) With horse–hoarse merger. toured toward ˈtɔːd Non-rhotic with horse–hoarse merger. whored hoard ˈhɔː(r)d With horse–hoarse merger. whored also has an alternative pronunciation that is already a perfect homophone of hoard. whored horde ˈhɔː(r)d With horse–hoarse merger. whored also has an alternative pronunciation that is already a perfect homophone of horde. your yaw ˈjɔː Non-rhotic. your yore ˈjɔː(r) With horse–hoarse merger. you're yaw ˈjɔː Non-rhotic. you're yore ˈjɔː(r) With horse–hoarse merger. Pure–poor split

The pure–poor split is a phonemic split that occurs in Australian and New Zealand English that causes the centring diphthong /ʊə/ to disappear and split into /ʉːə/ (a sequence of two separate monophthongs) and /oː/ (a long monophthong), causing pure, cure, and tour to rhyme with fewer, and poor, moor and sure to rhyme with for and paw.[22][23]

Where the /ʊə/ becomes /ʉːə/ and where it becomes /oː/ is not very predictable. But words spelt with -oor that originally had /ʊə/ become /oː/ perhaps by influence of the words door and floor which rhyme with store in all dialects of English.

A similar split occurs in many varieties of North American English that causes /ʊr/ to disappear and split into /ɝ/ and /ɔr/, causing pure, cure, and lure to rhyme with fir, and poor and moor to rhyme with store and for.

Card–cord merger

The card–cord merger is a merger of Early Modern English [ɑr] with [ɒr], resulting in homophony of pairs like card/cord, barn/born and far/for. It is roughly similar to the father–bother merger, but before r. The merger is found in some Caribbean English accents, in some versions of the West Country accent in England, and in some Southern and Western U.S. accents.[24][25] Areas where the merger occurs includes central Texas, Utah, and St. Louis.[citation needed] Dialects with the card–cord merger don't have the horse–hoarse merger. The merger is disappearing in the United States, being replaced by the more common horse–hoarse merger that other regions have.

Homophonous pairs /ɑr/ /ɒr/ IPA are or ˈɑr barn born ˈbɑrn card chord ˈkɑrd card cord ˈkɑrd carn corn ˈkɑrn dark dork ˈdɑrk far for ˈfɑr farm form ˈfɑrm lard lord ˈlɑrd spark spork ˈspɑrk stark stork ˈstɑrk tart tort ˈtɑrt Horse–hoarse merger

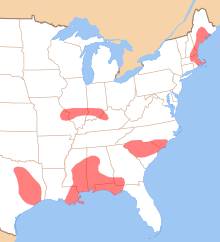

Red areas show where the distinction between horse and hoarse is still made by many speakers in the U.S. Map based on Labov, Ash, and Boberg[1]

Red areas show where the distinction between horse and hoarse is still made by many speakers in the U.S. Map based on Labov, Ash, and Boberg[1]

The horse–hoarse merger is the merger of the vowels /ɔ/ and /o/ before historic /r/, making pairs of words like horse/hoarse, for/four, war/wore, or/oar, morning/mourning etc. homophones. This merger occurs in most varieties of English. In accents that have the merger horse and hoarse are both pronounced [hɔː(ɹ)s], but in accents that do not have the merger hoarse is pronounced differently, usually [hoɹs] in rhotic and [hoəs] or the like in non-rhotic accents. Non-merging accents include Scottish English, Hiberno-English, the Boston accent, Southern American English, African American Vernacular English, most varieties of Caribbean English, and Indian English.[26][27]

The distinction was made in traditional Received Pronunciation as represented in the first and second editions of the Oxford English Dictionary. The IPA symbols used are /ɔː/ for horse and /ɔə/ for hoarse.

In the United States, the merger is quite recent in some parts of the country. For example, Kurath and McDavid[28] based on fieldwork performed in the 1930s, shows the contrast robustly present in the speech of Vermont, northern and western New York State, Virginia, central and southern West Virginia, and North Carolina; but Labov, Ash, and Boberg[29] based on telephone surveys conducted in the 1990s, shows these areas as having almost completely undergone the merger. And even in areas where the distinction is still made, the acoustic difference between the [ɔr] of horse and the [or] of hoarse is rather small for many speakers.[30]

The two groups of words merged by this rule are called the lexical sets NORTH (including horse) and the FORCE (including hoarse) by Wells (1982). Etymologically, the NORTH words had /ɒɹ/ and the FORCE words had /oːɹ/.

The orthography of a word often signals whether it belongs in the NORTH set or the FORCE set. The spellings war, quar, aur, and word-final or indicate NORTH (e.g. quarter, war, warm, warn, aura, aural, Thor). The spellings oVr or orV (where V stands for a vowel) indicate FORCE (e.g. board, coarse, hoarse, door, floor, course, pour, oral, more, historian, moron, glory). Words spelled or followed by a consonant mostly belong with NORTH, but the following exceptions are listed with FORCE by Wells (1982):

- the past participles borne (but not born), shorn, sworn, torn and worn

- some (but not all) words where or follows a labial consonant:

- Borneo

- afford, force, ford, forge, fort (but not fortress), forth

- deport, export, import (but not important), porch, pork, port, portend, portent, porter, portion, portrait, proportion, report, sport, support

- divorce

- sword

- the word corps (but not corpse; corps is a perfect homophone of core)

- the word horde (a perfect homophone of hoard)

Homophonous pairs /oə/ /ɔː/ IPA Notes board bawd ˈbɔːd Non-rhotic. boarder border ˈbɔː(r)də(r) bored bawd ˈbɔːd Non-rhotic. borne bawn ˈbɔːn Non-rhotic. borne born ˈbɔː(r)n Bourne bawn ˈbɔːn Non-rhotic. Bourne born ˈbɔː(r)n core caw ˈkɔː Non-rhotic. cored cawed ˈkɔːd Non-rhotic. cored chord ˈkɔː(r)d cored cord ˈkɔː(r)d corps caw ˈkɔː Non-rhotic. court caught ˈkɔːt Non-rhotic. door daw ˈdɔː Non-rhotic. floor flaw ˈflɔː Non-rhotic. fore for ˈfɔː(r) fort fought ˈfɔːt Non-rhotic. four for ˈfɔː(r) gored gaud ˈɡɔː Non-rhotic. hoarse horse ˈhɔː(r)s hoarse hoss[1] ˈhɔːs Non-rhotic. lore law ˈlɔː Non-rhotic. more maw ˈmɔː Non-rhotic. mourning morning ˈmɔː(r)nɪŋ oar awe ˈɔː Non-rhotic. oar or ˈɔː(r) ore awe ˈɔː Non-rhotic. ore or ˈɔː(r) pore paw ˈpɔː Non-rhotic. pour paw ˈpɔː Non-rhotic. roar raw ˈrɔː Non-rhotic. shore shaw ˈʃɔː Non-rhotic. shorn Sean ˈʃɔːn Non-rhotic. shorn Shawn ˈʃɔːn Non-rhotic. soar saw ˈsɔː Non-rhotic. soared sawed ˈsɔːd Non-rhotic. sore saw ˈsɔː Non-rhotic. source sauce ˈsɔːs Non-rhotic. sword sawed ˈsɔːd Non-rhotic. tore taw ˈtɔː Non-rhotic. tore tor ˈtɔː(r) wore war ˈwɔː(r) worn warn ˈwɔː(r)n yore yaw ˈjɔː Non-rhotic. Cork–quark merger

The cork–quark merger is the merger of the sequences /kɔr/ and /kwɔr/, making cork and quark homophones. This merger is generally observed to be strongest in American English.[2] Even more minimal pairs become homophonous when accompanied with the horse–hoarse merger, which most General American accents also have.

Homophonous pairs /kɔr/ /kwɔr/ IPA Notes coral quarrel ˈkɔrəl In General American. Corey quarry ˈkɔri In General American. core 'em quorum ˈkɔrəm With horse–hoarse merger. cork quark ˈkɔrk corn Quorn ˈkɔrn court quart ˈkɔrt With horse–hoarse merger. courter quarter ˈkɔrtər With horse–hoarse merger. See also

- Phonological history of the English language

- Phonological history of English vowels

- coil–curl merger

- English phonology

- History of the English language

- Vocalic r

Sound samples

- ^ http://www.alt-usage-english.org/mmm_bc.wav Sample of a speaker with the Mary–marry–merry merger Text: "Mary, dear, make me merry; say you'll marry me."

- ^ http://www.alt-usage-english.org/mmm_rf.wav Sample of a speaker with the three-way distinction

- ^ http://ldc.upenn.edu/myl/thurr.mp3 Text: "I like the way you do that right there (right there)/Swing your hips when you're walkin', let down your hair (let down your hair)/I like the way you do that right there (right there)/Lick your lips when you're talkin', that make me stare"

Notes

- ^ http://students.csci.unt.edu/~kun/tln.html[dead link]

- ^ Wells, pp. 479–485.

- ^ http://cfprod01.imt.uwm.edu/Dept/FLL/linguistics/dialect/staticmaps/q_15.html

- ^ Wells, p. 480-82

- ^ Labov et al., p. 54, 56

- ^ Labov et al., p. 56

- ^ Wells, pp. 201–2, 244

- ^ Labov et al., pp. 54, 238

- ^ Shitara

- ^ Wells, pp. 338, 512, 547, 557, 608

- ^ Wells, pp. 199–203, 407, 444

- ^ Wells, pp. 372, 421, 444

- ^ Kurath and McDavid, pp. 117–18 and maps 33–36.

- ^ http://www.ausp.memphis.edu/phonology/#Vocalic

- ^ Wells, pp. 238–42, 286, 292–93, 339

- ^ Kurath and McDavid, p. 122

- ^ Wells, p. 164

- ^ Hammond, p. 52

- ^ Wells, pp. 56, 65–66, 164, 237, 287–88

- ^ Kenyon, pp. 233–34

- ^ Wells, p. 549

- ^ http://www.ling.mq.edu.au/speech/phonetics/phonology/features/auseng_features.html

- ^ Macquarie University Dictionary and other dictionaries of Australian English

- ^ Labov et al., pp. 51–53

- ^ Wells, pp. 158, 160, 347, 483, 548, 576–77, 582, 587

- ^ Labov et al., p. 52

- ^ http://www.ling.upenn.edu/phonoatlas/Atlas_chapters/Ch8/Ch8.html

- ^ Wells, pp. 159–61, 234–36, 287, 408, 421, 483, 549–50, 557, 579, 626

- ^ Kurath and McDavid, map 44

- ^ Labov et al., map 8.2

- ^ Labov et al., p. 51

References

- ^ hoss, Dictionary.com

- ^ antimoon.com: Discussion of regional pronunciations of quirk, cork and quark.

- Hammond, Michael. (1999). The Phonology of English. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-823797-9.

- Kenyon, John S. (1951). American Pronunciation (10th ed.). Ann Arbor, Michigan: George Wahr Publishing Company. ISBN 1884739083.

- Kurath, Hans, and Raven I. McDavid (1961). The Pronunciation of English in the Atlantic States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-8173-0129-1.

- Labov, Wiliam, Sharon Ash, and Charles Boberg (2006). The Atlas of North American English. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-016746-8.

- Shitara, Yuko (1993). "A survey of American pronunciation preferences". Speech Hearing and Language 7: 201–32.

- Wells, John C. (1982). Accents of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521229197:

- ISBN 0-521-22919-7 (vol. 1);

- ISBN 0-521-24224-X (vol. 2);

- ISBN 0-521-24225-8 (vol. 3).

History of the English language Proto-English · Old English · Anglo-Norman language · Middle English · Early Modern English · Modern English

Phonological history Vowels Great Vowel Shift · short A · low back vowels · high back vowels · high front vowels · diphthongs · changes before historic l · changes before historic r · trisyllabic laxing

Consonants Categories:- English dialects

- Splits and mergers in English phonology

- The fur vowel is also used in:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.