- Phonological history of English fricatives and affricates

-

The phonological history of English fricatives and affricates is part of the phonological history of the English language in terms of changes in the phonology of fricative and affricate consonants.

Contents

H dropping and h adding

H dropping

H dropping is a linguistic term used to describe the omission of initial /h/ in words like house, heat, and hangover in many dialects of English, such as Cockney and Estuary English. The same phenomenon occurs in many other languages, such as Serbian, and Late Latin, the ancestor of the modern Romance languages. Interestingly, both French and Spanish acquired new initial [h] in mediæval times, but these were later lost in both languages in a "second round" of h dropping (however, some dialects of Spanish re-acquired /h/ from Spanish /x/). Many dialects of Dutch also feature h dropping, particularly the southwestern variants. It is also known from several Scandinavian dialects, for instance Älvdalsmål and the dialect of Roslagen where it is found already in Runic Swedish.

It is debated amongst linguists which words originally had an initial /h/ sound. Words such as horrible, habit and harmony all had no such sound in their earliest English form nor were they originally spelt with an h, but it is now widely considered incorrect to drop the /h/ in the pronunciation.[1]

H dropping in English is found in all dialects in the weak forms of function words like he, him, her, his, had, and have; and, in most dialects, in all forms of the pronoun it – the older form hit survives as the strong form in a few dialects such as Southern American English and also occurs in the Scots language. Because the /h/ of unstressed have is usually dropped, the word is usually pronounced /əv/ in phrases like should have, would have, and could have. These are usually spelled out as "should've", "would've", and "could've".

See also

Homophonous pairs /h/ /-/ IPA had ad ˈæd had add ˈæd hail ail ˈeɪl hail ale ˈeɪl hair air ˈɛː(r), ˈeɪr hair ere ˈɛː(r) hair heir ˈɛː(r), ˈeɪr haired erred ˈɛː(r)d hale ail ˈeɪl hale ale ˈeɪl, ˈeːl hall all ˈɔːl ham am ˈæm hand and ˈænd hap app ˈæp hare air ˈɛː(r) hare ere ˈɛː(r), ˈeːr hare heir ˈɛː(r) hark ark ˈɑː(r)k harm arm ˈɑː(r)m hart art ˈɑː(r)t has as ˈæz hat at ˈæt hate ate ˈeɪt hate eight ˈeɪt haul all ˈɔːl haunt aunt ˈɑːnt hawk auk ˈɔːk head Ed ˈɛd heard erred ˈɜː(r)d, ˈɛrd heart art ˈɑː(r)t heat eat ˈiːt hedge edge ˈɛdʒ heist iced ˈaɪst herd erred ˈɜː(r)d, ˈɛrd hew ewe ˈjuː, ˈ(j)ɪu hew yew ˈjuː, ˈjɪu hew you ˈjuː hi aye ˈaɪ hi eye ˈaɪ hi I ˈaɪ hid id ˈɪd high aye ˈaɪ high eye ˈaɪ high I ˈaɪ higher ire ˈaɪə(r) hill ill ˈɪl hire ire ˈaɪə(r), ˈaɪr his is ˈɪz hit it ˈɪt hitch itch ˈɪtʃ hoard awed ˈɔːd hoard oared ˈɔː(r)d, ˈoə(r)d, ˈoːrd hoarder order ˈɔː(r)də(r) hoe O ˈoʊ, ˈoː hoe oh ˈoʊ, ˈoː hoe owe ˈoʊ hold old ˈoʊld holed old ˈoʊld hone own ˈoʊn horde awed ˈɔːd horde oared ˈɔː(r)d, ˈoə(r)d, ˈoːrd how ow ˈaʊ howl owl ˈaʊl hue ewe ˈjuː, ˈ(j)ɪuː hue yew ˈjuː, ˈjɪuː hue you ˈjuː Hugh ewe ˈjuː, ˈ(j)ɪuː Hugh yew ˈjuː, ˈjɪuː Hugh you ˈjuː hurl earl ˈjuː whore awe ˈɔː whore oar ˈɔː(r), ˈoə(r), ˈoːr whore or /ˈɔː(r) whore ore ˈɔː(r), ˈoə(r), ˈoːr whored awed ˈɔːd whored oared ˈɔː(r)d, ˈoə(r)d, ˈoːrd who's ooze ˈuːz whose ooze ˈuːz H adding

The opposite of aitch dropping, so-called aitch adding, is a hypercorrection found in typically h dropping accents of English. Commonly found in literature from late Victorian times to the early 20th century, holds that some lower-class people consistently drop h in words that should have it, while adding h to words that should not have it. An example from the musical My Fair Lady is, "In 'Artford, 'Ereford, and 'Ampshire, 'urricanes 'ardly hever 'appen". Another is in C.S. Lewis' The Magician's Nephew: "Three cheers for the Hempress of Colney 'Atch". In practice, however, it would appear that h adding is more of a stylistic prosodic effect, being found on some words receiving particular emphasis, regardless of whether those words are h-initial or vowel-initial in the standard language.

Words borrowed from French frequently begin with the letter h but not with the sound /h/. Examples include hour, heir, hono(u)r and honest. In some cases, spelling pronunciation has introduced the sound /h/ into such words, as in humble, hotel and (for most speakers) historic. Spelling pronunciation has also added /h/ to the English English pronunciation of herb, /hɜːb/, while American English retains the older pronunciation /ɝb/.

Velar fricatives

Taut–taught merger

The taut–taught merger is a process that occurs in modern English that causes /x/ to be dropped in words like thought, night, daughter etc.[2][3][4]

The phoneme /x/ was previously distinguished as [ç] after front vowels, [x] after back vowels. [ç] and sometimes [x] was lost in most dialects with compensatory lengthening of the previous vowels. /nɪxt/ [nɪçt] > /niːt/, later > /naɪt/ "night" by the Great Vowel Shift.

/x/ sometimes became /f/, with shortening of previous vowel.

Inconsistent development of [x] combined with ambiguity of ou (either /ou/ or /uː/ in Early Middle English) produced multiple reflexes of orthographic ough. Compare Modern English through /θruː/, though /ðoʊ/, bough /baʊ/, cough /kɒf/ or /kɑf/, rough /rʌf/.

Some accents in northern England show slightly different changes, for example, night as /niːt/ (neat) and in the dialectal words owt and nowt (from aught and naught, pronounced like out and nout, meaning anything and nothing). Also, in Northern England, the distinction between wait and weight is often preserved, so those speakers lack the wait–weight merger.

Wait–weight merger

The wait–weight merger is the merger of the Middle English sound sequences /ɛi/ (as in wait) and /ɛix/ (as in weight) that occurs in most dialects of English.[5]

The main exceptions are in Northern England, for example in many Yorkshire accents, where these sequences are often kept distinct, so that wait /weːt/ is distinct from weight /wɛɪt/ and late /leːt/ does not rhyme with eight [ɛɪt].

The distinction between wait and weight is an old one that goes back to a diphthongisation of Middle English /ɛ/ before the fricative /x/ which was represented by gh in English. So in words like weight /ɛ/ became /ɛɪ/ and subsequently /x/ was lost as in Standard English, but the diphthong remained.

Wait on the other hand is a Norman French loan word (which in turn was a Germanic loan) and had the Middle English diphthong [ai] that was also found in words like day. This diphthong merged with the reflex of Middle English /aː/ (as in late) and both ended up as /eː/ in the accents of parts of northern England, hence the distinction wait /weːt/ vs. weight /wɛɪt/.

Lock–loch merger

The lock–loch merger is a phonemic merger of /k/ and /x/ that is starting to occur in some Scottish English dialects, making lock and loch homonyms as /lɔk/. Many other varieties of English have borrowed foreign and Scottish /x/ as /k/, and so not all people who pronounce "lock" and "loch" alike exhibit the merger[clarification needed].[6][7]

The English spoken in Scotland has traditionally been known for having an extra consonant /x/, but that is starting to disappear among some younger speakers in Glasgow. This merger was investigated by auditory and acoustic analysis on a sample of children from Glasgow pronouncing words that traditionally have /x/ in Scottish English.

Dental fricatives

See also

- The then–thyn split was a phonemic split of the Old English phoneme /θ/ into two phonemes /ð/ and /θ/ occurring in Early Middle English which resulted in then and thyn (thin)'s starting with different initial consonant, /ð/ and /θ/.

- Th fronting is a merger that occurs (historically independently) in Cockney, Newfoundland English, African American Vernacular English, and Liberian English (though the details differ among those accents), by which Early Modern English /θ, ð/ merge with /f, v/.

- Th stopping is the realization of the dental fricatives [θ, ð] as the stops, [t, d] which occurs in several dialects of English.

- Th-alveolarization is the pronunciation of the dental fricatives /θ, ð/ as the alveolar fricatives /s, z/

- Th-debuccalization is the pronunciation of the dental fricative /θ/ as the glottal fricative /h/ when it occurs at the beginning of a word or intervocalically, occurring in many varieties of Scottish English.

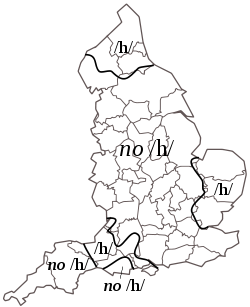

Initial fricative voicing

Initial fricative voicing is a process that occurs in the West Country where the fricatives /s/, /f/, /θ/, /ʃ/ and /h/ are voiced to /z/, /v/, /ð/, /ʒ/ and /ɦ/ when they occur at the beginning of a word. In these accents, sing and farm are pronounced /zɪŋ/ and /vɑːrm/. As seen in H dropping, many of these areas also drop /ɦ/ altogether.

Homophonous pairs /f θ s ʃ/ /v ð z ʒ/ IPA Notes face vase ˈveɪs, ˈveːs faze vase ˈveɪz, ˈveːz fail vail ˈveɪl fail vale ˈveɪl With pane–pain merger. fail veil ˈveɪl fairy vary ˈvɛːri With pane–pain merger. fan van ˈvæn fast vast ˈvɑːst, ˈvæst fat vat ˈvæt fault vault ˈvɔːlt faun Vaughan ˈvɔːn fawn Vaughan ˈvɔːn fear veer ˈvɪː(r), ˈviːr With meet–meat merger. feel veal ˈviːl With meet–meat merger. feign vain ˈveɪn With wait–weight merger. feign vane ˈveɪn With pane–pain merger and wait–weight merger. feign vein ˈveɪn With wait–weight merger. felt veldt ˈvelt fend vend ˈvɛnd fern Verne ˈvɜː(r)n, ˈvɛrn ferry very ˈvɛri fessed vest ˈvɛst fest vest ˈvɛst file vial ˈvaɪl With vile–vial merger. file vile ˈvaɪl fin Vin ˈvɪn find vined ˈvaɪnd fine vine ˈvaɪn fined vined ˈvaɪnd Finn Vin ˈvɪn first versed ˈvɜː(r)st With fern–fir–fur merger. foal vole ˈvoʊl, ˈvoːl folly volley ˈvɒli foul vowel ˈvaʊl With vile–vial merger. fowl vowel ˈvaʊl With vile–vial merger. phase vase ˈveɪz, ˈveːz sack Zach ˈzæk sag zag ˈzæɡ said zed ˈzɛd sane Zane ˈzeɪn sap zap ˈzæp sewn zone ˈzoʊn With toe–tow merger. sip zip ˈzɪp sit zit ˈzɪt sown zone ˈzoʊn Sue zoo ˈzuː With yod dropping after s. thigh thy ˈðaɪ thou (thousand) thou (thee) ˈðaʊ A similar phenomenon happened in both German and Dutch.

S-retraction

S-retraction is a process where "s" is pronounced as a retracted variant of [s] auditorily closer to [ʃ]. S-retraction occurs in Glaswegian, in Scotland.[6]

Seal–zeal merger

Seal–zeal merger is a phenomenon occurring in Hong Kong English where the phonemes /s/ and /z/ are both pronounced /s/ making pairs like "seal" and "zeal", and "racing" and "razing" homonyms.[8]

Pleasure–pressure merger

Pleasure–pressure merger is a phenomenon occurring in Hong Kong English where the phonemes /ʃ/ and /ʒ/ are both pronounced /ʃ/ making "pleasure" and "pressure" rhyme.[8]

Sip–ship merger

The sip–ship merger is a phenomenon occurring in some Asian and African varieties of English where the phonemes /s/ and /ʃ/ are not distinguished. As a result, pairs like "sip" and "ship", "sue" and "shoe" etc. are homophones.[9]

In the cartoon series, South Park, this pronunciation is made fun of by recurring character Tuong Lu Kim's distinctive pronunciation of the word, "city".

Ship–chip merger

The ship–chip merger is phenomenon occurring for some speakers of Zulu English where the phonemes /ʃ/ and /tʃ/ are not distinguished. As a result, "ship" and "chip" are homophones.[10]

Zip–gyp merger

The zip–gyp merger is a phenomenon occurring for some speakers of Indian English where /z/ and /dʒ/ are not distinguished, making "zip" and "gyp" homophonous as /dʒɪp/, and "raze" sound like "rage".

See also

- Phonological history of the English language

- Phonological history of English consonants

- intervocalic alveolar flapping

- t glottalization

- rhotic and nonrhotic accents

- l vocalization

- Hard and soft c

References

- ^ http://www.askoxford.com/worldofwords/wordfrom/aitches/?view=uk

- ^ http://web.archive.org/web/20040703025114/http://www.uni-mainz.de/FB/Philologie-II/fb1413/roesel/seminar0203/regional_varieties/Scotland.htm

- ^ *http://216.239.51.104/search?q=cache:9zbJpPgRmfMJ:www.phon.ucl.ac.uk/home/wells/English%2520accents_6.ppt

- ^ http://www1.uni-hamburg.de/peter.siemund/Articles/English%2520(Variationstypologie).pdf

- ^ (Wells 1982: 192–94, 337, 357, 384–85, 498)

- ^ a b Annexe 4: Linguistic Variables

- ^ http://www.essex.ac.uk/linguistics/archive/viewconf2000/abstracts.html

- ^ a b Microsoft PowerPoint - HKE-1-3.ppt

- ^ http://books.google.com/books?vid=ISBN0521830206&id=OqUBUgW_Ax8C&pg=PA518&lpg=PA518&dq=%22sue+and+shoe%22&sig=NNtDLd5Sq7Te-AQbDcq-iqp9K0c

- ^ Rodrik Wade, MA Thesis, Ch 4: Structural characteristics of Zulu English at the Wayback Machine (archived May 17, 2008)

Categories:- Phonology

- Language histories

- English phonology

- Splits and mergers in English phonology

- Scottish English

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.