- Ottoman architecture

-

Culture of the

Ottoman Empire

Visual Arts Architecture · Miniature · Pottery · Calligraphy Performing Arts Shadowplay · Meddah · Dance · Music Languages and literature Ottoman Turkish · Poetry · Prose Sports Oil wrestling · Archery · Cirit Other Cuisine · Carpets · Clothing Ottoman architecture or Turkish architecture is the architecture of the Ottoman Empire which emerged in Bursa and Edirne in 14th and 15th centuries. The architecture of the empire developed from the earlier Seljuk architecture and was influenced by the Byzantine architecture, Iranian as well as Islamic Mamluk traditions after the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans.[1][2][3] For almost 400 years Byzantine architectural artifacts such as the church of Hagia Sophia served as models for many of the Ottoman mosques.[3] Overall, Ottoman architecture has been described as Ottoman architecture synthesized with architectural traditions of the Mediterranean and the Middle East.[4]

The Ottomans achieved the highest level architecture in their lands hence or since. They mastered the technique of building vast inner spaces confined by seemingly weightless yet massive domes, and achieving perfect harmony between inner and outer spaces, as well as articulated light and shadow. Islamic religious architecture which until then consisted of simple buildings with extensive decorations, was transformed by the Ottomans through a dynamic architectural vocabulary of vaults, domes, semi domes and columns. The mosque was transformed from being a cramped and dark chamber with arabesque-covered walls into a sanctuary of aesthetic and technical balance, refined elegance and a hint of heavenly transcendence.

Today, one finds remnants of Ottoman architecture in certain parts of its former territories under decay.[5]

Early architecture

In their homeland in Central Asia, Turks lived in dome-like tents appropriate to their natural surroundings. These tents later influenced Turkish architecture and ornamental arts. When the Seljuks first arrived in Iran, they encountered an architecture based on old traditions. Integrating this with elements from their own traditions, the Seljuks produced new types of structures, most notably the "medrese" (Muslim theological schools). The first medreses - known as Nizāmīyah - were constructed in the 11th century by the famous minister Nizam al-Mulk, during the time of Alp Arslan and Malik Shah I. The most important ones are the three government medreses in Nishapur, Tus and Baghdad and the Hargerd Medrese in Khorasan. Another area in which the Seljuks contributed to architecture is that of tomb monument. These can be divided into two types: vaults and large dome-like mausoleums (called Türbes).

The Ribat-e Sharif and the Ribat-e Anushirvan are examples of surviving 12th century Seljuq caravanserais, which offered shelter for travellers. Seljuq buildings generally incorporate brick, while the inner and outer walls are decorated in a material made by mixing marble, powder, lime and plaster. In typical buildings of the Anatolian Seljuq period, the major construction material was wood, laid horizontally except along windows and doors where columns were considered more decorative.

Early Ottoman period

With the establishment of the Ottoman empire, the years 1300-1453 constitute the early or first Ottoman period, when Ottoman art was in search of new ideas. This period witnessed three types of mosques: tiered, single-domed and subline-angled mosques. The Hacı Özbek Mosque (1333) in İznik, the first important center of Ottoman art, is the first example of an Ottoman single-domed mosque...

Bursa Period (1299-1437)

The domed architectural style evolved from Bursa and Edirne. The Holy Mosque in Bursa was the first Seljuk mosque to be converted into a domed one. Edirne was the last Ottoman capital before Istanbul, and it is here that we witness the final stages in the architectural development that culminated in the construction of the great mosques of Istanbul. The buildings constructed in Istanbul during the period between the capture of the city and the construction of the Istanbul Bayezid II Mosque are also considered works of the early period. Among these are the Fatih Mosque (1470), Mahmutpaşa Mosque, the tiled palace and Topkapı Palace. The Ottomans integrated mosques into the community and added soup kitchens, theological schools, hospitals, Turkish baths and tombs.

Classical period (1437-1703)

The Classical period of Ottoman architecture is to a large degree a development of the prior approaches as they evolved over the 15th and early 16th centuries and the start of the Classical period is strongly associated with the works of Mimar Sinan.[6][7] In this period, Ottoman architecture, especially with the works, and under the influence, of Sinan, saw a new unification and harmonization of the various architectural parts, elements and influences that Ottoman architecture had previously absorbed but which had not yet been harmonized into a collective whole.[6] Taking heavily from the Byzantine tradition, and in particular the influence of the Hagia Sophia, Classical Ottoman architecture was, as before, ultimately a syncretic blend of numerous influences and adaptations for Ottoman needs.[6][7] In what may be the most emblematic of the structures of this period, the classical mosques designed by Sinan and those after him used a dome-based structure, similar to that of Hagia Sophia, but among other things changed the proportions, opened the interior of the structure and freed it from the collonades and other structural elements that broke up the inside of Hagia Sophia and other Byzantine churches, and added more light, with greater emphasis on the use of lighting and shadow with a huge volume of windows.[6][7] These developments were themselves both a mixture of influence from Hagia Sophia and similar Byzantine structures, as well as the result of the developments of Ottoman architecture from 1400 on, which, in the words of Godfrey Goodwin, had already "achieved that poetic interplay of shaded and sunlit interiors which pleased Le Corbusier."[6]

During the classical period mosque plans changed to include inner and outer courtyards. The inner courtyard and the mosque were inseparable. The master architect of the classical period, Mimar Sinan, was born in 1492 in Kayseri and died in Istanbul in the year 1588. Sinan started a new era in world architecture, creating 334 buildings in various cities. Mimar Sinan's first important work was the Şehzade Mosque completed in 1548. His second significant work was the Süleymaniye Mosque and the surrounding complex, built for Suleiman the Magnificent. The Selimiye Mosque in Edirne was built during the years 1568-74, when Sinan was in his prime as an architect. The Rüstempaşa, Mihriman Sultan, Ibrahimpasa Mosques and the Şehzade, Kanuni Sultan Süleyman, Roxelana and Selim II mausoleums are among Sinan's most renowned works. Most classical period design used the Byzantine architecture of the neighboring Balkans as its base, and from there, ethnic elements were added creating a different architectural style.[citation needed]

16th century Ottoman architects set a powerful precedent for future structures. Buildings such as the Blue Mosque were mere imitations of the Sinan blueprint. During the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries, Ottoman architecture was influenced by European styles. The first examples of Baroque architecture appeared in the 18th century, in buildings such as the Harem section of the Topkapı Palace, the Aynalıkavak Palace and the Nuruosmaniye Mosque, the latter also having a famous Baroque fountain. Numerous buildings were built in the 19th century with an eclectic mix of various European styles such as Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassical architecture, including the Dolmabahçe Palace, Beylerbeyi Palace, Dolmabahçe Mosque and the Ortaköy Mosque. Some mosques were even designed with an Ottoman adaptation of the Neo-Gothic style, such as the Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Mosque in the Aksaray quarter, and the Yıldız Hamidiye Mosque in the Yıldız quarter of Beşiktaş, close to the Yıldız Palace and the Barbaros Boulevard. Towards the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Istanbul became one of the leading centers of the Art Nouveau movement, with architects such as Alexander Vallaury and Raimondo D'Aronco designing a number of prominent buildings in this style. In the early 20th century, Turkish architects such as Mimar Kemaleddin Bey and Mimar Vedat Bey (Vedat Tek) pioneered a "Turkish neoclassical" architectural style (Turkish: Birinci Ulusal Mimarlık Akımı), using many elements from the Turkish buildings of the past centuries. The most important examples of this style include the Büyük Postane (Grand Post Office) and Vakıf Han office buildings in Istanbul's Sirkeci quarter.[citation needed]

Examples of Ottoman architecture of the classical period, aside from Turkey, can also be seen in the Balkans, Hungary, Egypt, Tunisia and Algiers, where mosques, bridges, fountains and schools were built.

Modernization period

During the reign of Ahmed III (1703–1730) and under the impetus of his grand vizier İbrahim Paşa, a period of peace ensued. Due to its relations with France, Ottoman architecture began to be influenced by the Baroque and Rococo styles that were popular in Europe. The Baroque style is noted as first being developed by Seljuk Turks, according to a number of academics.[8][9] Examples of the creation of this art form can be witnessed in Divriği hospital and mosque a UNESCO world heritage site, Sivas Çifteminare, Konya İnce Minare museum and many more. It is often called the Seljuk Baroque portal. From here it emerged again in Italy, and later grew in popularity among the Turks during the Ottoman era. Various visitors and envoys were sent to European cities, especially to Paris, to experience the contemporary European customs and life. The decorative elements of the European Baroque and Rococo influenced even the religious Ottoman architecture. On the other hand, Mellin, a French architect, was invited by a sister of Sultan Selim III to Istanbul and depicted the Bosphorus shores and the pleasure mansions (yalıs) placed next to the sea. During a thirty-year period known as the Tulip Period, all eyes were turned to the West, and instead of monumental and classical works, villas and pavilions were built around Istanbul. However, it was about this time when the construction on the Ishak Pasha Palace in Eastern Anatolia was going on, (1685–1784).

Tulip Period (1703-1757)

Beginning with this period, the upper class and the elites in the Ottoman empire started to use the open and public areas frequently. The traditional, introverted manner of the society began to change. Fountains and waterside residences such as Aynalıkavak Kasrı became popular. A water canal (other name is Cetvel-i Sim), a picnic area (Kağıthane) were established as recreational area. Although the tulip age ended with the Patrona Halil uprising, it became a model for attitudes of westernization. During the years 1720-1890, Ottoman architecture deviated from the principals of classical times. With Ahmed III’s death, Mahmud I took the throne (1730–1754). It was during this period that Baroque-style mosques were starting to be constructed.Baroque Period (1757-1808)

Circular, wavy and curved lines are predominant in the structures of this period. Major examples are Nur-u Osmaniye Mosque, Zeynep Sultan Mosque, Laleli Mosque, Fatih Tomb, Laleli Çukurçeşme Inn, Birgi Çakırağa Mansion, Aynali Kavak Summerplace, Taksim Military Barracks and Selimiye Barracks. Mimar Tahir is the important architect of the time.

Empire Period (1808-1876)

Nusretiye Mosque, Ortaköy Mosque, Sultan Mahmut Tomb, Galata Lodge of Mevlevi Derviches, Dolmabahçe Palace, Çırağan Palace, Beylerbeyi Palace, Sadullah Pasha Yalı, Kuleli Barracks are the important examples of this style developed parallel with the westernization process. Architects from the Balyan family and the Fossati brothers were the leading ones of the time.

Late period (1876-1922): The "National Architectural Renaissance"

The final period of architecture in the Ottoman Empire, developed after 1900 and in particular put into effect after the Young Turks took power in 1908-1909, is what was then called the "National Architectural Renaissance" and which gave rise to the style since referred to as the First National Style of Turkish architecture.[10] The approach in this period was an Ottoman revival style, a reaction to influences in the previous 200 years that had come to be considered "foreign," such as Baroque and Neoclassical architecture, and was intended to promote Ottoman patriotism and self-identity.[10] This was actually an entirely new style of architecture, related to earlier Ottoman architecture in rather the same manner was other roughly contemporaneous "revival" architectures, such as Gothic Revival Architecture, related to their stylistic inspirations.[10] Like other "revival" architectures, "Ottoman Revival" architecture of this period was based on modern construction techniques and materials such as reinforced concrete, iron, steel, and often glass roofs, and in many cases used what was essentially a Beaux-Arts structure with outward stylistic motifs associated with the original architecture from which it was inspired.[10] It focused outwardly on forms and motifs seen to be traditionally "Ottoman," such as pointed arches, ornate tile decoration, wide roof overhangs with supporting brackets, domes over towers or corners, etc.[10]

Originally, this style was meant to promote the patriotism and identity of the historically multi-ethnic Ottoman Empire, but by the end of WWI and the creation of the Turkish Republic, it was adopted by the republican Turkish nationalists to promote a new Turkish sense of patriotism.[10] In this role, it continued into, and influenced the later architecture of, the Republic of Turkey.

One of the earliest and most important examples of this style is the Istanbul Central Post Office in Sirkeci, completed in 1909 and designed by Vedat Tek (also known as Vedat Bey).[10]

Other important extant examples include the Istanbul ferryboat terminals built between 1913 and 1917, such as the Besiktas terminal by Ali Talat Bey (1913), the Haydarpasa terminal by Vedat Tek (1913), and the Buyukada terminal by Mihran Azaryan (1915).[10] Another important extant example is the Sultanahmet Jail, now the Four Seasons Hotel Sultanahmet.

In Ankara, the earliest building in the style is the building that now houses the War of Independence Museum and served as the first house of the Turkish Republic's National Assembly in 1920.[10] It was built in 1917 by Ismail Hasif Bey as the local headquarters for the Young Turks' Committee of Union and Progress.[10]

İn the late Ottoman Empire Löle Gizo Mimarbaşı contributed some important architecture in Mardin Cercıs Murat Konağı ,Şehidiye minaret,The P.T.T. building are some of his work. Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Mosque, Sheikh Zafir Group of Buildings, Haydarpasha School of Medicine, Duyun-u Umumiye Building, Istanbul Title Deed Office, Large Postoffice Buildings, Laleli Harikzedegan Apartments are the important structures of this period when an eclectic style was dominant. Raimondo D'Aronco and Alexander Vallaury were the leading architects of this period in Istanbul. Apart from Vallaury and D'Aronco, the other leading architects who made important contributions to the late Ottoman architecture in Istanbul included the architects of the Armenian Balyan family, William James Smith, August Jachmund, Mimar Kemaleddin Bey, Vedat Tek and Giulio Mongeri.

Gallery

-

Tekkiye Mosque, built on the orders of Suleiman the Magnificent in Syria

-

Interior view of Khan As'ad Pasha in Syria

-

The Grand Serail was built by the Ottoman Turks and is now the headquarters of the Prime Minister of Lebanon.

-

The Jaffa Clock Tower was built to commemorate the silver jubilee of the reign of Sultan Abd al-Hamid II in Israel.

-

The Khan al-Umdan is the largest and best preserved Ottoman inn in Israel.

-

Stari Most in Bosnia and Herzegovina

-

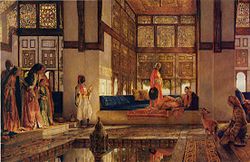

Svrzo's House in Bosnia and Herzegovina

-

Rác Baths in Hungary

-

Tsisdarakis Mosque in Athens

-

Osman Shah's mosque at Trikala

-

Sultanahmet Jail in Istanbul, in the First National Style

-

Pertevniyal Valide Sultan Mosque in Istanbul

-

Kılıç Ali Pasha Complex in Istanbul

-

Karaağaç Railway Station in Edirne

-

Ottoman architecture in Novi Pazar

-

Et'hem Bey Mosque and Clock Tower in Tirana

-

Isa Bey Mosque in Skopje's Old Bazaar

-

Aziziye mosque in Batumi, Georgia (now does not exist).

See also

- Islamic architecture

- Byzantine architecture

- Khanqah - known in Turkish as a tekke

- Yalıs

- Külliyes

- Türbes

- Khans

- Çeşmes

- Mosques commissioned by the Ottoman dynasty

History of architecture Neolithic · Ancient Egyptian · Coptic · Chinese · Dravidian · Mayan · Mesopotamian · Classical · Mesoamerican · Achaemenid Persia · Ancient Greek · Roman · Incan · Sassanid · Byzantine · Islamic · Newari · Buddhist · Somali · Persian · Pre-Romanesque · Romanesque · Romano-Gothic · Gothic · Plateresque · Manueline · Hoysala · Vijayanagara · Western Chalukya · Renaissance · Ottoman · Mughal · Baroque · Biedermeier · Classicism · Neoclassical · Historicism · Gründerzeit · Gothic Revival · Neo-Renaissance · Neo-Baroque · Rationalism · Modernisme · Art Nouveau · Expressionism · Modern · Postmodern- A Guide to Ottoman Bulgaria" by Dimana Trankova, Anthony Georgieff and Professor Hristo Matanov; published by Vagabond Media, Sofia, 2011 [[1]]

References

- ^ Necipoğlu, Gülru (1995). Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Volume 12. Leiden : E.J. Brill. p. 60. ISBN 9789004103146. OCLC 33228759. http://books.google.com/?id=RtbeBrAHhxgC&pg=PA60&lpg=PA60&dq=Ottoman+Architecture. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1989). Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction. Leiden ; New York : E.J. Brill,. p. 29. ISBN 9004086773. http://books.google.com/?id=INsmT6zjAl8C&pg=RA1-PA29&lpg=RA1-PA29&dq=Ottoman+Architecture. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ a b Rice, John Gordon; Robert Clifford Ostergren (2005). "The Europeans: A Geography of People, Culture, and Environment". The Professional geographer (Guilford Press) 57 (4). ISBN 9780898622720. ISSN 0033-0124. http://books.google.com/?id=wgPSUQ873scC&pg=PA193&lpg=PA193&dq=Ottoman+Architecture. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ Grabar, Oleg (1985). Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture. Volume 3. Leiden : E.J. Brill,. ISBN 9004076115. http://books.google.com/?id=Xu_L_FJRvUIC&pg=PA92&lpg=PA92&dq=Ottoman+Architecture. Retrieved 2007-08-20.

- ^ Çevikalp, Mesut (2008-08-27). "Historian Kiel spends half century tracing history of Ottoman art". Today's Zaman. http://todayszaman.com/tz-web/detaylar.do?load=detay&link=151325. Retrieved 2008-09-17.

- ^ a b c d e Goodwin, Godfrey (1993). Sinan: Ottoman Architecture & its Values Today. London: Saqi Books. ISBN 0863561721.

- ^ a b c Stratton, Arthur (1972). Sinan. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 684-12582-X.

- ^ Hoag, John D (1975). Islamic architecture. London: Faber. ISBN 0571148689.

- ^ Aslanapa, Oktay (1971). Turkish art and architecture. London: Faber. ISBN 0571087817.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bozdogan, Sibel (2001). Modernism and Nation Building: Turkish Architectural Culture in the Early Republic. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295981520.

Further reading

- Goodwin G., "A History of Ottoman Architecture"; Thames & Hudson Ltd., London, reprinted 2003; ISBN 0-500-27429-0

- Dŏgan K., "Ottoman Architecture"; Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 9-781851-496044

External links

- Turkish Architecture

- Similarities between Ottoman,Local and Byzantine architecture (PDF)

- A varied photo collection of different Ottoman styles and buildings

- Extensive information on Architect Sinan's works in Istanbul

Architecture of Europe By country Albania · Armenia · Austria · Azerbaijan · Belarus · Belgium · Bosnia and Herzegovina · Bulgaria · Croatia · Cyprus · Czech Republic · Denmark · Estonia · Finland · France · Georgia · Germany · Greece · Hungary · Iceland · Ireland · Italy · Kazakhstan · Latvia · Lithuania · Luxembourg · Macedonia · Malta · Moldova · Montenegro · Netherlands · Norway · Poland · Portugal · Romania · Russia · Serbia · Slovakia · Slovenia · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom (England · Scotland)History Ancient Greek · Roman · Byzantine · Pre-Romanesque · Romanesque · Romano-Gothic · Gothic · Renaissance · Baroque · Biedermeier · Classicism · Neoclassical · Historicism · Gründerzeit · Gothic Revival · Neo-Renaissance · Neo-Baroque · Rationalism · Modernisme · Art Nouveau · Expressionism · Modern · PostmodernArchitecture of Asia Sovereign

states- Afghanistan

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- Bhutan

- Brunei

- Burma (Myanmar)

- Cambodia

- People's Republic of China

- Cyprus

- East Timor (Timor-Leste)

- Egypt

- Georgia

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Israel

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- North Korea

- South Korea

- Kuwait

- Kyrgyzstan

- Laos

- Lebanon

- Malaysia

- Maldives

- Mongolia

- Nepal

- Oman

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Qatar

- Russia

- Saudi Arabia

- Singapore

- Sri Lanka

- Syria

- Tajikistan

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

- Uzbekistan

- Vietnam

- Yemen

States with limited

recognition- Abkhazia

- Nagorno-Karabakh

- Northern Cyprus

- Palestine

- Republic of China (Taiwan)

- South Ossetia

Dependencies and

other territories- Christmas Island

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Hong Kong

- Macau

Categories:- Ottoman architecture

- Medieval architecture

- Architectural styles

- Islamic architecture

- Turkish architecture

-

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.