- History of Georgia Tech

-

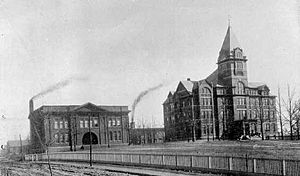

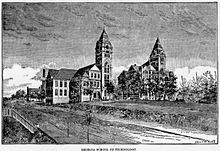

An early photograph of Georgia Tech depicts the shop building (left) and Tech Tower (right).

An early photograph of Georgia Tech depicts the shop building (left) and Tech Tower (right).

The history of the Georgia Institute of Technology can be traced back to Reconstruction-era plans to develop the industrial base of the Southern United States. Founded on October 13, 1885 in Atlanta, Georgia as the Georgia School of Technology, the university opened in 1888 after the construction of Tech Tower and a shop building and only offered one degree in mechanical engineering. By 1901, degrees in electrical, civil, textile, and chemical engineering were also offered. In 1948, the name was changed to the Georgia Institute of Technology to reflect its evolution from an engineering school to a full technical institute and research university.

Georgia Tech is the birthplace of two other Georgia universities: Georgia State University and Southern Polytechnic State University. Georgia Tech's Evening School of Commerce, established in 1912 and moved to the University of Georgia in 1931, was independently established as Georgia State University in 1955. Although Georgia Tech did not officially allow women to enroll until 1952 (and did not fully integrate the curriculum until 1968), the night school enrolled female students as early as the fall of 1917. The Southern Technical Institute (now Southern Polytechnic State University) was created as an extension of Georgia Tech in 1948 as a technical trade school for World War II veterans and became an independent university in 1981.

The Great Depression saw a consistent squeeze on Georgia Tech's budget, but World War II-inspired research activity combined with post-World War II enrollment more than compensated for the school's difficulties. Unlike the University of Georgia, Georgia Tech's longtime rival, Tech desegregated peacefully and without a court order in 1961. Similarly, it did not experience any protests due to the Vietnam War. The growth of the graduate and research programs combined with diminishing federal support for universities in the 1980s led President John Patrick Crecine to restructure the university in 1988 amid significant controversy. The 1990s were marked by continued expansion of the undergraduate programs and the satellite campuses in Savannah, Georgia and Metz, France. In 1996, Georgia Tech was the site of the athletes' village and a venue for a number of athletic events for the Summer Olympics. Recently, the school has gradually improved its academic rankings and has paid significant attention to modernizing the campus, increasing historically low retention rates, and establishing degree options emphasizing research and international perspectives.

Contents

Establishment

As noted by a historical marker on the large hill in Central Campus, the site occupied by the school's first buildings once held fortifications built to protect Atlanta during the Atlanta Campaign of the American Civil War. The surrender of the city took place on the southwestern boundary of the modern Georgia Tech campus in 1864.[1] The next twenty years were a time of rapid industrial expansion; during this period, Georgia's manufacturing capital, railroad track mileage, and property values would each increase by a factor of three to four.[2]

“ I would much rather be author of a law establishing such a school than to be Governor of Georgia.[2] ” —Nathaniel Edwin Harris, 1882

The establishment of a school of technology was proposed in 1882 during the Reconstruction period. Two former Confederate officers, Major John Fletcher Hanson and Nathaniel Edwin Harris, who became prominent citizens in the town of Macon, Georgia after the war, strongly believed that the South needed to improve its technology to compete with the industrial revolution that was occurring throughout the North.[2][3][4] Many Southerners at this time agreed with this idea, known as the "New South Creed."[5] Its strongest proponent was Henry W. Grady, editor of the Atlanta Constitution during the 1880s.[5] A technology school was thought necessary because the American South of that era was mostly agrarian, and few technical developments were occurring. Georgians needed technical training to develop the state's industry.[3][4]

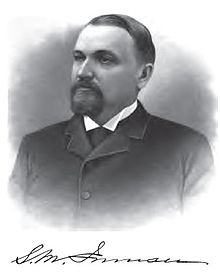

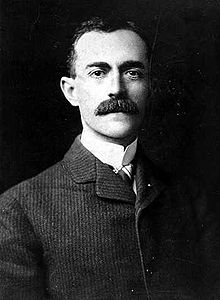

Nathaniel Edwin Harris, the founder of the Georgia School of Technology, served on its Board of Trustees from its establishment until his death.

Nathaniel Edwin Harris, the founder of the Georgia School of Technology, served on its Board of Trustees from its establishment until his death.

With authorization from the Georgia state legislature, Harris and a committee of prominent Georgians visited renowned technology schools in the Northeast in 1883; these included the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Worcester, Massachusetts, Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, and The Cooper Union in New York City. Using these examples, the committee reported that the Worcester model, which stressed a combination of "theory and practice," was the embodiment of the best conception of industrial education."[2] The "practice" component of the Worcester model included student employment and production of consumer items to generate revenue for the school.[6]

When the committee returned, they submitted their findings to the Georgia General Assembly as House Bill 732 on July 24, 1883. The bill, written by Harris, met significant opposition from various sources and was defeated. Reasons for opposition included the general resistance to education, specifically technical education, concerns voiced by agricultural interests, and fiscal concerns relating to the limited treasury of the Georgia government; the state's 1877 constitution prevented the state from spending beyond its means as a reactionary measure to excessive spending by "carpetbaggers and Negro leaders."[2]

In February 1883, Harris submitted a second version, this time with the political support of contemporary political leaders Joseph M. Terrell and R. B. Russel as well as the popular support of the influential State Agricultural Society and the leaders of the University of Georgia, the latter of which would be the "parent college" of any state technical school.[2] In 1885, House Bill 732 was submitted and passed the House 94-62. The bill was passed in the Senate with two amendments, and the amended bill was defeated in the House 65-53. After back-room work by Harris, the bill finally passed 69-44. On October 13, 1885, Georgia Governor Henry D. McDaniel signed the bill to create and fund the new school.[7][8] The legislature then established a committee to determine the location of the new school.[7] The school was officially established, and subsequent efforts to repeal the law were suppressed by supporter and Speaker of the House W. A. Little.[2]

“ Section I. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of this State, and it is hereby enacted by authority of the same, That there shall be established in connection with the State University, and forming one of the departments thereof, a technological School for the education and training of students in the industrial and mechanical arts. Said school shall be located, equipped and conducted as hereinafter provided.[8] ” —Georgia General Assembly House Bill 732, 1885

Governor McDaniel appointed a commission in January 1886 to organize and run the school. This commission elected Harris chairman, a position he would hold until his death. Other members included Samuel M. Inman, Oliver S. Porter, Judge Columbus Heard, and Edward R. Hodgson; each was known either for political or industrial experience.[2] Their first task was to select a location for the new school. Letters were sent to communities throughout the state, and five bids were presented by the October 1, 1886 deadline: Athens, Atlanta, Macon, Penfield, and Milledgeville. The commission inspected the proposed sites from October 7, 1886 to October 18, 1886. Patrick Hues Mell, the president of the University of Georgia at that time, believed that it should be located in Athens with the University's main campus, like the Agricultural and Mechanical School.[9]

The committee members voted exclusively for their respective home cities until the 21st ballot when Porter switched to Atlanta; on the 24th ballot, Atlanta finally emerged victorious.[2] Students at the University of Georgia burned Judge Heard in effigy after the final vote was announced.[2] Atlanta's bid included $50,000 from the city, $20,000 from private citizens (including $5,000 from Samuel M. Inman),[10] and a $2,500 in guaranteed yearly support, along with a gift of 4 acres (16,000 m2) of land from Atlanta pioneer Richard Peters instead of the initially proposed site in Atlanta's bid, which was near land that Lemuel P. Grant was developing, including Grant Park.[2]

The school's new location was bounded on the south by North Avenue, and on the west by Cherry Street.[7] Peters then sold five adjoining acres of land to the state for $10,000.[7] This land was situated on what was then Atlanta's northern city limits.[9] The act that created the school had also appropriated $65,000 towards the construction of new buildings.[2]

Early years

- Includes the administration of Isaac S. Hopkins (1888–1896)

“ The time and attention of students will be duly proportioned between scholastic and mechanical pursuits, and special prominence will be given to the element of practice in every department.[11] ” —Georgia School of Technology Prospectus, 1888

Isaac S. Hopkins, president of the Georgia School of Technology from 1888 to 1896

Isaac S. Hopkins, president of the Georgia School of Technology from 1888 to 1896

The Georgia School of Technology opened its doors in the fall of 1888 with only two buildings, under the leadership of professor and pastor Isaac S. Hopkins.[3] One building (now Tech Tower, the main administrative complex) had classrooms to teach students; the other featured a workshop with a foundry, forge, boiler room, and engine room. It was designed specifically as a "contract shop" where students would work to produce goods to sell, creating revenue for the school while the students learned vocational skills in a "hands-on" manner.[4][5] Such a method was seen as appropriate given the Southern United States' need for industrial development.[5] The two buildings were equal in size and staffing (five professors and five shop supervisors)[12] to show the importance of teaching both the mind and the hands. At the time, there was some disagreement as to whether the machine shop should have been used to turn a profit.[3][6] The contract shop system ended in 1896 due to its lack of profitability, after which point the items produced were used to furnish the offices and dorms on the campus.[4]

An 1888 engraving illustrates the modest Georgia School of Technology campus.

An 1888 engraving illustrates the modest Georgia School of Technology campus.

The first class of students at the Georgia School of Technology was small and homogeneous, and educational options were limited. 85 students signed up on the first registration day, October 7, 1888, and the enrollment for the first year climbed to a total of 129 by January 7, 1889.[2][13][14][15] The first student to register was William H. Glenn.[16] All but one or two of the students were from Georgia.[17] Tuition was free for Georgia residents and $150 ($3,654 today) for out-of-state students.[11] The only degree offered was a Bachelor of Science in Mechanical Engineering, and no elective courses were available. All students were required to follow exactly the same program, which was so rigorous that nearly two thirds of the first class failed to complete it.[14] The first graduating class consisted of two students in 1890, Henry L. Smith and George G. Crawford, who decided their graduation order on the flip of a coin.[2]

Tech began its football program with several students forming a loose-knit troop of footballers called the Blacksmiths. The first season saw Tech play three games and lose all three. Discouraged by these results, the Blacksmiths sought a coach to improve their record. Leonard Wood, a local Atlantan, heard of Tech's football struggles and volunteered to player-coach the team.[18] In 1893, Tech played its first game against the University of Georgia (Georgia). Tech defeated Georgia 28-6 for the school's first-ever victory. The angry Georgia fans threw stones and other debris at the Tech players during and after the game. The poor treatment of the Blacksmiths by the Georgia faithful gave birth to the rivalry now known as Clean, Old-Fashioned Hate.[19][20]

The first publication of "Ramblin' Wreck" in the 1908 Blue Print, entitled "What Causes Whitlock to Blush." The words "hell" and "helluva" were too hot to print: at the bottom, it explains that "Owing to the melting of the type, it has been impossible to print the parts of the above song represented by blank spaces."

The first publication of "Ramblin' Wreck" in the 1908 Blue Print, entitled "What Causes Whitlock to Blush." The words "hell" and "helluva" were too hot to print: at the bottom, it explains that "Owing to the melting of the type, it has been impossible to print the parts of the above song represented by blank spaces."

The words to Georgia Tech's famous fight song, Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia Tech, are said to have come from an early baseball game against rival Georgia.[21][22][23] Some sources credit Billy Walthall, a member of the first four-year graduating class, with the lyrics.[24][25] According to a 1954 article in Sports Illustrated, "Ramblin' Wreck" was written around 1893 by a Tech football player on his way to an Auburn game.[24] In 1905, Georgia Tech adopted it as its official fight song, in roughly the current form, although it had apparently been the unofficial fight song for several years.[21][26] It was published for the first time in the school's first yearbook, the 1908 Blueprint.[21][27] Entitled "What causes Whitlock to Blush,"[28] words such as "hell" and "helluva" were censored as "certain words [are] too hot to print."[23] After Michael A. Greenblatt, the first bandmaster of the Georgia Tech Marching Band, heard the band playing the song to the tune of Charles Ives's A Son of a Gambolier,[21] he wrote a modern musical version.[25] In 1911, Frank Roman succeeded Greenblatt as bandmaster; Roman embellished the song with trumpet flourishes and publicized it.[21][27] Roman copyrighted the song in 1919.[24][25]

Tech's first student publication was the Technologian, which ran for a short time in 1891.[29] The next student publication was established in 1894 and was called The Georgia Tech.[30] The Georgia Tech published a "Commencement Issue" that reviewed sporting events and gave information about each class.[30] The Technique was founded in 1911; its first issue was published on November 17, 1911 by editors Albert Blohm and E.A. Turner, and the content revolved around the upcoming rivalry football game against the University of Georgia.[31][32][33] The Technique has been published weekly ever since, with the exception of a brief period that the paper was published twice weekly.[34] The Georgia Tech and the Technique operated separately for several years following the Technique's establishment, though the two publications eventually merged in 1916.[33]

Engineering school

- Includes the administration of Lyman Hall (1896–1905)

Captain Lyman Hall, president of the Georgia School of Technology from 1896 until his death in 1905

Captain Lyman Hall, president of the Georgia School of Technology from 1896 until his death in 1905

In 1888, Captain Lyman Hall was appointed Georgia Tech's first mathematics professor, a position he held until his appointment as the school's second president in 1896. He had a solid background in engineering due to his time at West Point and often incorporated surveying and other engineering applications into his coursework. He had an energetic personality and quickly assumed a leadership position among the faculty. As president, Hall was noted for his aggressive fundraising and improvements to the school, including his special project, the A. French Textile School.[35] In February 1899, Georgia Tech opened the first textile engineering school in the Southern United States,[36] with $10,000 from the Georgia General Assembly, $20,000 of donated machinery, and $13,500 from supporters.[37] It named the A. French Textile School, after its chief donor and supporter, Aaron S. French. The textile engineering program would move to the Harrison Hightower Textile Engineering Building in 1949.[36][38]

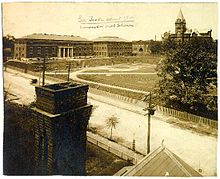

Georgia Tech around 1900, with Tech Tower in the background

Georgia Tech around 1900, with Tech Tower in the background

Lyman Hall's other goals included enlarging Tech and attracting more students, so he expanded the school's offerings beyond mechanical engineering; the new degrees introduced during Hall's administration included electrical engineering and civil engineering in December 1896, textile engineering in February 1899, and engineering chemistry in January 1901.[39][40][41][42] Hall also became infamous as a disciplinarian, even suspending the entire senior class of 1901 for returning from Christmas vacation a day late.[43]

The Tech football team noted a particular coach during their initial abysmal run: their first game of the 1903 season was a 73-0 destruction at the hands of John Heisman's Clemson Tigers. Tech went after Heisman following the 1903 season, and hired him for $2,250 a year and 30% of the home ticket sales. Heisman would not disappoint the Tech faithful as his first season was an 8-1-1 performance.[44] He would also muster a 5-game winning streak against the hated Georgia Bulldogs from 1904-1908 before incidents lead up to the cutting of athletic ties with Georgia in 1919.[19]

Lyman Hall died on August 16, 1905 during a vacation at a New York health resort. His death while still in office was attributed to stress from his strenuous fund raising activities (this time, for a new Chemistry building).[45] Later that year, the school's trustees named the new chemistry building the "Lyman Hall Laboratory of Chemistry" in his honor.[45][46][47]

On October 20, 1905, U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt visited the Georgia Tech campus. On the steps of Tech Tower, Roosevelt presented a speech about the importance of technological education:

“ America can be the first nation only by the kind of training and effort which is developed and is symbolized in institutions of this kind... Every triumph of engineering skill credited to an American is credited to America. It is incumbent upon you to do well, not only for your individual sakes, but for the sake of that collective American citizenship which dominates the American nation.[48] ” He then shook hands with every student.[49] Tech was later visited by president-elect William H. Taft on January 16, 1909 and president Franklin D. Roosevelt on November 29, 1935.[48]

World War I

- Includes the administration of Kenneth G. Matheson (1906–1922)

Grant Field and the east stands around 1912

Grant Field and the east stands around 1912

Upon his hiring in 1904, John Heisman (for whom the Heisman Trophy is named) insisted that the Institute acquire its own football field. Previously, the team had used area parks, especially the playing fields of Piedmont Park.[50] Georgia Tech took out a seven-year lease on what is now the southern end of Grant Field, although the land wasn't adequate for sports, due to its unleveled, rocky nature. In 1905, Heisman had 300 convict laborers clear rocks, remove tree stumps, and level out the field for play; Tech students then built a grandstand on the property. The land was purchased by 1913, and John W. Grant donated $15,000 ($332,222.22 today) towards the construction of the field's first permanent stands; the field was named Grant Field in honor of the donor's deceased son, Hugh Inman Grant.[50][51]

Attempts at forming an alumni association had been made since 1896, until a charter was applied for by J. B. McCrary and William H. Glenn on June 28, 1906 and was approved two years later by Fulton County on June 20, 1908.[2] The Georgia Tech Alumni Association published its first annual report in 1908, but was largely dormant due to the pressures of World War I. The organization played an important role in the 1920s Greater Georgia Tech Campaign, which consolidated all existing alumni clubs and funded a significant expansion of Georgia Tech's campus.[52][2][53]

Georgia Tech's Evening School of Commerce began holding classes in 1912.[54][55] The school admitted its first female student in 1917, although the state legislature did not officially authorize attendance by women until 1920.[55][56] Anna Teitelbaum Wise became the first female graduate in 1919 and went on to become Georgia Tech's first female faculty member the following year.[55][56][57]

World War I caused several changes at the school. During the conflict and for some time afterwards, Georgia Tech hosted a school for cadet aviators and supply officers, army technicians, and started the a Reserve Officer Training Corps unit that would become a permanent addition to the school, the first in the Southern United States.[58] World War I would also affect the school academically: the United States government asked and paid for an automotive school for army officers, a rehabilitation program for disabled soldiers, and a geology department.[58] Federal aid also helped to establish Tech's Industrial Education Department, courtesy of the Smith-Hughes Act of 1917.[17] The war also placed on hold extensive fundraising efforts for a new power plant, and made it difficult to find engineers willing to teach at the school; Matheson's tour of Harvard, Yale, Princeton, Columbia, and MIT in 1919 failed to secure a single hire, as none of the students wished to work for such low wages.[59]

Kenneth G. Matheson, president of the Georgia School of Technology from 1906 to 1922

Kenneth G. Matheson, president of the Georgia School of Technology from 1906 to 1922

The bitter rivalry between Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia flared up in 1919, when UGA mocked Tech's continuation of football during the United States' involvement in World War I. Because Tech was a military training ground, it had a complete assembly of male students. Many schools, such as Georgia, lost all of their able-bodied male students to the war effort, forcing them to temporarily suspend football during the war. In fact, Georgia did not play a game from 1917-1918.[60]

When UGA renewed its program in 1919, their student body staged a parade, which mocked Tech's continuation of football during times of war. The parade featured a tank shaped float marked "Argonne" with a sign "Georgia in France 1917" followed by an automobile with three people in Tech sweaters and caps bearing a sign "Tech in Atlanta".[61] A printed program was subsequently distributed in the stands with a similar point. While the Tech faculty was able to prevent a riot, no apology was made, and thus this act would lead directly to Tech cutting athletic ties with UGA and canceling several of UGA's home football games at Grant Field (UGA commonly used Grant Field as its home field).[61][62] Tech and UGA would not compete in athletics until the 1921 Southern Conference basketball tournament. Despite intense pressure on Tech to make amends, President Matheson stated that he would never change his mind unless "due apologies" were offered, and if he was overruled, he would resign.[63] Regular season competition would not renew until after Matheson's retirement in a 1925 agreement between the two institutions, negotiated by athletic directors J. B. Crenshaw and S. V. Sanford.[63][62]

In 1916, Georgia Tech's football team (still coached by John Heisman) defeated Cumberland 222-0, the largest margin of victory in college football history.[64] Cumberland's total net yardage was -28 (minus 28), and it had only one play for positive yards.[64][65] Cumberland beat Georgia Tech's baseball team 22 to 0 the previous year, reportedly with the help of professional players Cumberland had hired as "ringers," an act which infuriated Heisman.[64] Heisman coached Tech all the way up until 1919. He had amassed 104 wins over 16 seasons, and lead Tech to its first national title in 1917. However in 1919, he had divorced his wife and felt that he would embarrass his wife socially if he remained in Atlanta.[66] Heisman moved to Pennsylvania, leaving Tech's Yellow Jackets in the hands of William Alexander.

In its first decades of existence, the school slowly grew from a trade school into a university. However, the state and federal governments provided little initiative for the school to grow significantly until 1919.[5] That year, the Georgia General Assembly passed an act entitled "Establishing State Engineering Experiment Station at the Georgia School of Technology."[5][55] This change coincided with federal debate about the establishment of Engineering Experiment Stations in a move similar to the Hatch Act of 1887's establishment of agricultural experiment stations; each Engineering Experiment Station would be a consultant group dedicated to assisting a region's industrial efforts. Thus, the EES at Georgia Tech was established with the goal of the "encouragement of industries and commerce" within the state. However, the coinciding federal effort failed and the state did not finance the Georgia Tech's EES, so the new organization existed only on paper.[5][55]

The latter years of Matheson's presidency were marred by a chronic shortage of funds. In 1919-1920, the school had 1,365 students using facilities designed for 700, and had the same appropriation in 1919 that it had in 1915, $100,000; 1915's appropriation was worth $2,163,815.79 today, and 1919's appropriation was worth $1,269,884.17; the value was nearly halved due to inflation.[67] Matheson was able to acquire a $25,000 increase from the General Assembly that year. In 1920-1921, though, an increase of $125,000 (to $250,000) was passed but subsequently tabled due to differences between the House and Senate version of the bill unrelated to Tech.[17] To continue running the school, a frantic scramble for funds was undertaken, resulting in $40,000 from the General Education Board, $30,000 from a loan fund organized by the Georgia Rotary Club, and a grant from the Atlanta City Council. The University of Georgia, in a similar financial condition, was forced to cut its faculty's salary.[68] After this drama, the situation did not improve, though; in 1922-1923, only $112,500 of the requested $250,000 had been appropriated, leading Matheson to reluctantly start charging tuition of in-state students. The rates were $100 for in-state students ($1,310.36 today) and $175 for out-of-state students ($2,293.13 today). Georgia Tech still needed a $125,000 line of credit against its first professional fund-raising effort, the "Greater Georgia Tech Campaign".[68]

As Matheson was leaving for the presidency of Drexel Institute in late 1921, he wrote in the Atlanta Constitution that while Georgia Tech was "my first love" he found it a "humiliating burden" to get enough money from the state legislature to run and enlarge the school.[69] The Georgia Tech's Board of Trustees offered him a substantial pay increase, but his issue was with the politics of the time, and not with his financial situation.[69]

It was our hope and belief that by developing an efficient technological school, the legislators would amply support it. In spite of many handicaps and discouragements, we gave to the state what competent critics declare to be the second engineering college of the nation–the first [MIT], by the way, having recently spent $28,000,000 in its development. Notwithstanding... [soaring] enrollment, donated equipment totaling many thousands of dollars in value, $1,500,000 in subscriptions from friends and other evidences of growth, the legislatures of the past two summers have appropriated only half of the amount actually needed for the operation of the school. In 1920, upon the failure to appropriate the additional $100,000 necessary to keep Tech's doors open, I again became a modern Lazarus and successfully begged from Atlanta to New York the crumbs from the rich men's tables which a rich mother had denied... Again [in 1921] we have met the emergency at a disruptive and destructive cost which cannot be continued.—Kenneth G. Matheson, 1921Technological university

- Includes the administration of Marion L. Brittain (1922–1944)

Marion L. Brittain, president of the school from 1922 to 1944

Marion L. Brittain, president of the school from 1922 to 1944

On August 1, 1922, Marion L. Brittain was elected as the school's president. During his tenure, Brittain was able to convince the state of Georgia to increase the school's funding. He had noted in he 1923 annual report that "there are more students in Georgia Tech than in any other two colleges in Georgia, and we have the smallest appropriation of them all."[70] Additionally, a $300,000 grant ($3,946,800 today) from the Guggenheim Foundation allowed Brittain to establish the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aeronautics. In 1930, Brittain's decision to use the money for a School of Aeronautics was controversial; today, the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering boasts the second largest faculty in the United States behind MIT.[71] Other accomplishments during Brittain's administration included a doubling of Georgia Tech's enrollment,[72] accreditation for the Institute by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools,[73] and the creation of a new ceramic engineering department, building, and major that attracted the American Ceramics Society's national convention to Atlanta.[35][74]

During this era, William Alexander ran the Yellow Jackets football program. Tech resumed playing against the University of Georgia in 1925. In 1927, Alexander instituted "the Plan." Georgia was highly rated to start the 1927 season and justified their rating throughout the season going 9–0 in their first 9 games. Alexander's plan was to minimize injuries by benching his starters early no matter the score of every game before the UGA finale. On December 3, 1927, UGA rolled into Atlanta on the cusp of a National Title. Tech's well-rested starters shut out the Bulldogs 12–0 and ended any chance of UGA's first National Title.[2] Alexander's 1928 team would be the very first Tech team to attend a bowl game. The team had amassed a perfect 9–0 record and was invited to the 1929 Rose Bowl to play California. The game was a defensive struggle with the first points being scored after a Georgia Tech fumble. The loose ball was scooped up by California Center Roy Riegels and then accidentally returned in the wrong direction. Riegels returned the ball all the way to Georgia Tech's 3 yard line. After Riegels was finally tackled by his own team, the Bears opted to punt from the end zone. The punt was blocked and converted by Tech into a safety giving Tech a 2–0 lead. Cal would score a touchdown and point after but Tech would score another touchdown to finally win the game 8–7. This victory made Tech the 10–0 undefeated National Champions of 1928. It was Tech's second National Title in 11 years.[2][75]

In 1929, some Georgia Tech faculty members belonging to Sigma Xi started a Research Club at Tech that met once a month.[76] One of the monthly subjects, proposed by ceramic engineering professor W. Harry Vaughan, was a collection of issues related to Tech, such as library development, and the development of a state engineering station. Such a station would theoretically assist local businesses with engineering problems via Georgia Tech's established faculty and resources. This group investigated the forty existing engineering experiments at universities around the country, and the report was compiled by Harold Bunger, Montgomery Knight, and Vaughan in December 1929.[76]

The Great Depression threatened the already tentative nature of Georgia Tech's funding. In a speech on April 27, 1930, Brittain proposed that the university system be reorganized under a central body, rather than having each university under its own board.[77] As a result, the Georgia General Assembly and Governor Richard Russell, Jr. passed an act in 1931 that established the University System of Georgia and the corresponding Georgia Board of Regents; unfortunately for Brittain and Georgia Tech, the board was composed almost entirely of graduates of the University of Georgia. In its final act on January 7, 1932, the Tech Board of Trustees sent a letter to the chairman of the Georgia Board of Regents outlining its priorities for the school.[78] The Great Depression had effects on the school beyond organizational ones, though; enrollment dropped from 3,271 in 1931-1932 to a low of 2,482 in 1933-1934 and gradually increased afterwards. It also caused a decrease in funding from the State of Georgia, which in turn caused a decrease in faculty salaries, firing of graduate student assistants, and a postponing of building renovations.[79]

As a cost-saving move, effective on July 1, 1934, the Georgia Board of Regents transferred control of the relatively large Evening School of Commerce to the University of Georgia and moved the small civil engineering program at UGA to Tech.[55][56] The move was controversial, and both students and faculty protested against it, fearing that the Board of Regents would take other programs from Georgia Tech and reduce it to an engineering department of the University of Georgia. Brittian suggested that the lack of Georgia Tech alumni on the Board of Regents contributed to their decision. Despite the pressure, the Board of Regents held its ground.[80] Some of the other effects included dramatically reduced enrollment (as seen in the numbers above) and a significant impact on the athletic program, as most athletes were in the commerce school; the depression also eliminated athletic scholarships, which were replaced by a loan program.[81] Plans for an industrial management department to replace and supersede the Evening School of Commerce were first made in fall 1934. The department was established in 1935, and evolved into Tech's College of Management. The commerce school eventually split from UGA and became Georgia State University.[55][82]

In 1933, S. V. Sanford, president of the University of Georgia, proposed that a "technical research activity" be established at Tech. President Marion L. Brittain and Dean William Vernon Skiles asked for and examined the Research Club's 1929 report, and moved to create such an organization. Vaughan was selected as its acting director in April 1934, and $5,000 in funds were allocated directly from the Georgia Board of Regents.[5][76] These funds went to the previously established EES; its initial areas of focus were textiles, ceramics, and helicopter engineering.[83] Georgia Tech's EES later became the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI).[83]

The EES's early work was conducted in the basement of the Shop Building, and Vaughan's office was in the Aeronautical Engineering Building.[84] By 1938, the Engineering Experiment Station was producing useful technology, and the station needed a method to conduct contract work outside of the state budget.[5] Consequently, the Industrial Development Council (IDC) was formed. It was created by the Chancellor of the University System and the president of Georgia Power Company, and the Engineering Experiment Station's director was a member of the council.[5] The IDC later became the Georgia Tech Research Corporation, which currently serves as the sole contract organization for all Georgia Tech faculty and departments.[5]

In 1939, Engineering Experiment Station director Vaughan became the director of the School of Ceramic Engineering. He was the director of the station until 1940, when he accepted a higher-paying job at the Tennessee Valley Authority and was replaced at EES by Harold Bunger (the first chairman of Georgia Tech's chemical engineering department).[85][86] The ceramics department was subsequently (but temporarily) discontinued due to World War II, and all of the current students found wartime employment.[87] The department would be reincarnated after the war under the guidance of Lane Mitchell.[88]

The Cocking affair occurred in 1941 and 1942; Georgia governor Eugene Talmadge to exert direct control over the state's educational system, particularly through the firing of University of Georgia professor Walter Cocking, who had been hired to raise the relatively low academic standards at UGA's College of Education.[89] Governor Talmadge justified his actions by asserting that Cocking intended to integrate a part of the University of Georgia. Cocking's removal and the subsequent removal of members of the Georgia Board of Regents (including the vice chancellor) who disagreed with the decision were particularly controversial.[89] In response to the actions by Governor Talmadge, the Southern Association of Independent Schools withdrew accreditation from all Georgia state-supported colleges for whites, including Georgia Tech. The controversy was instrumental in Talmadge's loss in the 1943 gubernatorial elections to Ellis Arnall.[89]

World War II resulted in a dramatic increase of sponsored research, with the 1943-1944 budget being the first in which industry and government contracts exceeded the engineering station's other income (most notably, its state appropriation).[17] Director Vaughan had initially prepared the faculty for fewer incoming contracts as state had cut the station's appropriation by 40 percent, but increased support from industry and government eventually counteracted low state support.[17] The electronics and communications research that Directors Gerald Rosselot and James E. Boyd attracted is still a mainstay of GTRI research.[90] Two of the larger projects were a study on the propagation of electromagnetic waves, and United States Navy-sponsored radar research.[90]

Until the mid 1940s, the school required students to be able to create a simple electric motor regardless of their major.[91] During the second world war, as an engineering school with strong military ties through its ROTC program, Georgia Tech was swiftly enlisted for the war effort. In early 1942 the traditional nine-month semester system was replaced by a year-round trimester year, enabling students to complete their degrees a year earlier.[92] Under the plan, students were allowed to complete their engineering degrees while on active duty.[93] During World War II, Georgia Tech was one of only five U.S. colleges feeding the U.S. Navy's officer program, and was one of 131 colleges and universities nationally that took part in the V-12 Navy College Training Program which offered students a path to a Navy commission.[94]

Postwar changes and unrest

- Includes the administration of Blake R. Van Leer (1944–1956)

Founded as the "Georgia School of Technology," the school assumed its present name on July 1, 1948 to reflect a growing focus on advanced technological and scientific research.[95][96][97] The name change was first proposed on June 12, 1906, but never gained momentum until Van Leer's presidency.[98] Unlike similarly named universities (such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the California Institute of Technology), the Georgia Institute of Technology is a public institution. Concurrent with the name change, President Emeritus Marion L. Brittain published The Story of Georgia Tech, the first comprehensive, book-length history of the Institute.[87]

The Southern Technical Institute (STI) was established in 1948 in barracks on the campus of the Naval Air Station Atlanta (now DeKalb Peachtree Airport) in Chamblee, northeast of Atlanta.[99] At that time, all colleges in Georgia were considered extensions of the state's four research universities, and the Southern Technical Institute belonged to Georgia Tech. STI was established as an engineering technology school, to help military personnel returning from World War II gain a hands-on experience in technical fields. Around 1958, the school moved to Marietta, to land donated by Dobbins Air Force Base.[99] The Southern Technical Institute was later split from Georgia Tech in 1981. The split coincided with the separation of most other regional schools from the University of Georgia, Georgia State University, and Georgia Southern University.

The only women that had attended Georgia Tech did so through the School of Commerce. After it was removed in 1931, women were not able to enroll at the school until 1952.[57][100] In 1952 women could only enroll in programs not offered at other universities in Georgia. In 1968 the Board of Regents voted to allow women to enroll in all programs at Tech.[55][100] Also in 1968, Helen E. Grenga became Georgia Tech's first female professor.[101] The first women's dorm, Fulmer Hall, opened in 1969.[55] Women constituted 31.1% of the undergraduates and 25.5% of the graduate students enrolled in Fall 2010.[102]

The Hinman Research Building, which housed much of the Georgia Tech Research Institute at this time.

The Hinman Research Building, which housed much of the Georgia Tech Research Institute at this time.

Glen P. Robinson and six other Georgia Tech researchers (including Robinson's former professor and future EES director Jim Boyd and EES director Gerald Rosselot) each contributed US$100 and founded Scientific Associates (later known as Scientific Atlanta) on October 31, 1951 with the initial goal of marketing antenna structures being developed by the radar branch of the EES.[72][103][104] Robinson worked as the general manager without pay for the first year; after the fledgling company's first contract resulted in a $4,000 loss, Robinson (upon request) refunded five of the six other initial investors. Despite its rocky start, the company managed to become a success.[72] In 1951, there was a dispute over station finances and Rosselot's hand in the foundation of Scientific Atlanta against Georgia Tech vice president Cherry Emerson. Initially, Rosselot was president and CEO of Scientific Atlanta, but later handed off responsibility to Glen P. Robinson; at issue was potential conflicts of interest with his role at Georgia Tech and what, if any, role Georgia Tech should have in technology transfer to the marketplace.[103] Rosselot eventually resigned his post at Georgia Tech, but his participation ensured the eventual success of Scientific Atlanta and made way for further technology transfer efforts by Georgia Tech's VentureLab and the Advanced Technology Development Center.[17][103]

This period also saw a significant expansion in Georgia Tech's postgraduate education programs, driven largely by the Cold War and the launch of Sputnik; this effort received substantial support from the EES.[105][106] Despite its slow start, with the first Master of Science programs in the 1920s and the first Doctorate in 1946, the program became firmly established.[107] In 1952 alone, around 80 students earned graduate degrees while working at EES.[106] Herschel H. Cudd, EES director from 1952 to 1954, created a new promotion system for researchers that is still in use. Many EES researchers held the title of professor despite lacking a doctorate (or a comparable qualification for promotion as determined by the Georgia Board of Regents), something that irritated members of the teaching faculty. The new system, approved in spring 1953, used the Board of Regents' qualifications for promotion and mirrored the academic tenure track.[106]

Sugar Bowl controversy

After a successful (8-1-1) 1955 American football season, Tech was invited to play in the 1956 Sugar Bowl in New Orleans against the University of Pittsburgh. It would be the school's fifth straight bowl appearance under renowned coach Bobby Dodd. Pittsburgh had a black starting player, fullback Bobby Grier, but as Tech played a 1953 game against a desegregated Notre Dame team, and the University of Georgia had very recently played out-of-state games against desegregated opponents, president Blake Van Leer and the Tech Athletic Association saw the game's contract as acceptable. However, racial tension in the South was high following the recent Brown v. Board of Education decision.[108] Privately, Georgia Governor Marvin Griffin had given head coach Bobby Dodd his support, but surprised the campus and the state on Friday, December 2, 1955 by bowing to pressure from segregationists and sending a wire to the Georgia Board of Regents chairman, Robert A. Arnold, requesting not only that Tech not play the game, but all University System of Georgia teams play only segregated games.[108][109][110]

“ It is my request that athletic teams of units of the University System of Georgia not be permitted to engage in contests with other teams where the races are mixed on such teams or where segregation is not required among spectators at such events. The South stands at Armageddon. The battle is joined. We cannot make the slightest concession to the enemy in this dark and lamentable hour of struggle. There is no more difference in compromising integrity of race on the playing field than doing so in the classrooms. One break in the dike and the relentless seas will rush in and destroy us. We are in this fight 100 percent; not 98 percent, nor 75 percent, not 64 percent– but a full 100 percent. An immediate called meeting of the State Board of Regents to act on my request is vitally necessary at this time.[2] ” Enraged, Tech students organized an impromptu protest rally on campus. At midnight, a large group of students hung the governor in effigy and ignited a bonfire. They then marched to Five Points, the Georgia State Capitol, and the Georgia Governor's Mansion, hanging the governor in effigy at each location. The students did some minor damage to Governor's Mansion before the march was dispersed by state representative "Muggsy" Smith at 3:30 a.m.[108][109][110]

“ At the State Capitol, the boys pulled fire hoses from their racks, adorned the sculpt head of Civil War Hero John Gordon with an ashcan. A dozen effigies of Governor Marvin Griffin were hanged and burned during the students' march, which culminated in a 2 a.m. riot in front of the governor's mansion.[109] ” —Time Magazine

Van Leer's only comment to the media came on Saturday, December 3, 1955: "I am 60 years old and I have never broken a contract. I do not intend to start now."[108] At a tense meeting of the Board of Regents on Monday, it was decided that Georgia Tech would be allowed to play in the Sugar Bowl. The new policy was that "all laws, customs and traditions of host states would be respected but all games played in Georgia would be segregated," a policy that would remain until 1963.[108] The regents, with the exception of Tech alum David Rice, condemned the "riotous" behavior of Tech students. Rice instead criticized Marvin Griffin, and was lauded by The Technique as the "only man with the moral conviction to stand up against Griffin, ... and co."[111][109][110] Ironically, Tech defeated Pittsburgh 7-0 because of a pass interference call on the black player in question (Bobby Grier). Blake Van Leer died six weeks after this incident, on January 23, 1956; the stress of the incident was believed to have shortened his life.[111]

Integration and expansion

- Includes the administrations of Paul Weber (interim, February 1956-August 1957), Edwin D. Harrison (1957–1969) and Arthur G. Hansen (1969–1971)

Students gathered in the gym for a meeting with President Edwin D. Harrison before campus desegregation. "I told them if they couldn't behave, they couldn't stay in school."

Students gathered in the gym for a meeting with President Edwin D. Harrison before campus desegregation. "I told them if they couldn't behave, they couldn't stay in school."

(Courtesy Georgia Tech)After Georgia Tech president Blake Van Leer died in office, Paul Weber was acting president from January 1956 to August 1957, while still holding the title of Dean of Faculties. After the selection of a replacement in Edwin D. Harrison, Weber remained a Georgia Tech administrator and was named Vice President for Planning in 1966.[112]

On January 17, 1961, a meeting of 2,741 students in the Old Gym voted by an overwhelming majority to endorse integration of qualified applicants, regardless of race.[110][113] Three years after the meeting, and one year after the University of Georgia's violent integration, Georgia Tech became the first university in the Deep South to desegregate without a court order, with Ford Greene, Ralph A. Long, Jr. and Lawrence Michael Williams becoming Georgia Tech's first three African American students.[110][114] The ANAK Society claims to have met with their families and discreetly kept an eye on the students once they enrolled to ensure peaceful integration.[115]

There was little reaction to this by Tech students who, like the city of Atlanta described by former mayor William Hartsfield, were "too busy to hate."[110] However, Lester Maddox chose to close his restaurant (near the modern-day Burger Bowl) rather than desegregate, after losing a year-long legal battle in which he challenged the constitutionality of the public accommodations section (Title II) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[116] In 1965, John Gill became The Technique's first black editor, and Tech's first black professor, William Peace, joined the faculty of the Department of Social Sciences in 1968.[110][117]

The iconic 1930 Ford Model A Sport coupe that serves as the official mascot of the student body, the Ramblin' Wreck, was acquired in this era. The Wreck is present at all major sporting events and student body functions and leads the football team into Bobby Dodd Stadium at Historic Grant Field, a duty it has performed since 1961. Dean of Student Affairs Jim Dull recognized a need for an official Ramblin' Wreck when he observed the student body's fascination with classic cars. Fraternities, in particular, would parade around their House Wrecks as displays of school spirit and enthusiasm. It was considered a rite of passage to own a broken down vehicle.[118][119] In 1960, Dull began a search for a new official symbol to represent the Institute. He specifically wanted a classic pre-war Ford. Dull's search would entail newspaper ads, radio commercials, and other means to locate this vehicle. The search took him throughout the state and country, but no suitable vehicle was found until the autumn of 1960. Dean Dull spotted a polished 1930 Ford Model A outside of his apartment located in Towers Dormitory. The owner was Captain Ted J. Johnson, Atlanta's chief Delta Air Lines pilot.[118] When Johnson returned to his car, he found a note from Dean Dull attached to his windshield. Dull's note offered to purchase the car to serve as Georgia Tech's official mascot. Johnson, after great deliberation, agreed to take $1,000 but would eventually return the money in 1984 so that the car would be remembered as an official donation to Georgia Tech and the Alexander-Tharpe Fund.[120] The Ramblin' Wreck would be officially transferred to the Athletic Association on May 26, 1961.[121]

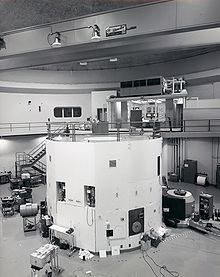

The $4.5 million Neely Research Reactor, which was built in 1963 in part due to James E. Boyd's influence.

The $4.5 million Neely Research Reactor, which was built in 1963 in part due to James E. Boyd's influence.

James E. Boyd was promoted to Assistant Director of Research at the Engineering Experiment Station in 1954, and then appointed as Director of the station from July 1, 1957 until 1961.[122] While at Georgia Tech, Boyd wrote an influential article about the role of research centers at institutes of technology, which argued that research should be integrated with education, and correspondingly involved undergraduates in his research.[122][123] Under Boyd's purview, the Engineering Experiment Station gained many electronics-related contracts, to the extent that an Electronics Division was created in 1959; it would focus on radar and communications.[124] The establishment of research facilities was also championed by Boyd. In 1955, Georgia Tech president Blake R. Van Leer appointed Boyd to Georgia Tech's Nuclear Science Committee.[122] The committee recommended the creation of a Radioisotopes Laboratory Facility and a large research reactor. The $4.5 million ($32,280,262 today) Frank H. Neely Research Reactor would be completed in 1963 and would be operational until 1996.[122]

Students across the nation protested the Vietnam War, even at similar institutions such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where students picketed and blocked access to the Draper Laboratory that was producing guidance systems for the Poseidon missile.[125] While The Technique did publish editorials against the United States' involvement, the Student Council easily defeated a bill endorsing the Vietnam Moratorium in the fall of 1969. While there were significant protests at other institutions that conducted military research, there were no protests against the military electronics research at the Georgia Tech Research Institute.[125]

There was similar nationwide concern over the United States' involvement in the Cambodian Civil War, resulting in the Kent State shootings, which in turn caused about 450 colleges to suspend classes.[17] In Georgia, the student response was largely restrained. Several hundred students at the University of Georgia marched on the home of president Frederick Corbet Davison demanding that the school be closed; consequently, all schools in the University System of Georgia were closed on May 8 and 9. While there were no protests at Tech, the students were still concerned over the events at Kent State; on May 8, four hundred students and faculty filled Bertha Square for a student-organized memorial, after which the students left quietly.[17]

A 1965 plan signaled the beginning of Tech's expansion to include what is now West Campus. The area west of Hemphill Avenue, for decades the campus' western border, was then a working-class multiracial neighborhood, and Hemphill itself was a major city thoroughfare connecting Buckhead, the Atlantic Steel Mill, Techwood Homes and Downtown.[126]

Reorganization and tradition

- Includes the administrations of James E. Boyd (interim, 1971-1972), Joseph M. Pettit (1972–1986) and John Patrick Crecine (1987–1994)

In a little under a month after James E. Boyd had assumed vice chancellorship of the University System of Georgia, then-Georgia Tech president Arthur G. Hansen resigned. Chancellor George L. Simpson appointed Boyd as Acting President of Georgia Tech, a post he held from May 1971 to March 1972.[122][127] As president, Boyd resolved two long-standing issues: the attempted takeover of the Georgia Tech Research Institute by departing president Hansen, and intense alumni pressure to fire football coach Bud Carson.[127][128] Boyd held the position until a president was found in March 1972; he was succeeded in the position by Joseph M. Pettit.[129]

Georgia Tech's mascot Buzz got his start in the 1970s. The original Georgia Tech Yellow Jacket mascot was Judi McNair who donned a homemade yellowjacket costume in 1972 and performed at home football games.[130] She rode on the Ramblin' Wreck and appears in the 1972 Georgia Tech Blueprint yearbook.[130] McNair's mascot was considered a great idea, as it was a big hit with the fans.[130] In 1979, McNair's idea for a Yellow Jacket was reintroduced by another Georgia Tech student, Richie Bland.[131] Bland, who was apparently unaware of McNair's prior initiative, paid $1,400 to have a local theme park costume designer make a yellowjacket costume that he first wore at a pep rally prior to the Tennessee football game.[131] Rather than obtain permission from Georgia Tech as Judi had done in 1972, this student simply snuck onto the field in costume during a football game and ran across the field.[131] The fans naturally believed that this costumed character was acting as an official member of the cheerleading squad and responded accordingly.[131] By 1980, this new incarnation of the yellow jacket mascot was given the name Buzz Bee and was adopted as an official mascot by Georgia Tech.[131] This new Buzz character would be the model for a new Georgia Tech emblem, designed in 1985 by Mike Lester.[7]

Thomas E. Stelson was Georgia Tech's Vice President for Research from 1974 to 1988, where he emphasized the importance of both basic research and applied research, given that the relative merits of each formed somewhat of a longstanding cultural war at the school.[132] An increased focus on research activities allowed more funding for academics, which allowed the school's ranking to start a long and continuing rise from the 20s.[132] Stelson simultaneously served as the interim director of the Georgia Tech Research Institute from 1975 to 1976,[133] during which time he reorganized the station into eight semi-autonomous laboratories in order to allow each to develop a specialization and clientele, a model that GTRI retains (with slight modifications) to this day.[132] From 1988 to 1990, Stelson was the Executive Vice President (Provost) of the Institute from 1988 until 1990. During Stelson's tenure at Georgia Tech, annual research spending grew from $8 million to $122 million.[133][134] Stelson had hoped to become the next president of Georgia Tech, but John Patrick Crecine was selected instead.[135]

The Institute celebrated its centennial in 1985. Among other observances, a time capsule was placed in the Student Center, and a team of historians wrote a comprehensive guide to Georgia Tech's history, Engineering the New South: Georgia Tech 1885-1985 (ISBN 0-8203-0784-X). A companion course was taught that year by two of the book's six authors. The course was offered again in 1999 as a swan song to the quarter system.[17][136]

“ There was controversy in every step. Management fought this, because they were the big losers... Crecine was under fire.[137] ” —August Geibelhaus

Institute President John Patrick Crecine proposed a controversial restructuring of the university in 1988. The Institute at that point had three colleges: the College of Engineering, the College of Management, and the catch-all COSALS, the College of Sciences and Liberal arts. Crecine reorganized the latter two into the College of Computing, the College of Sciences, and the Ivan Allen College of Management, Policy, and International Affairs.[137][138] Crecine announced the changes without asking for input, and consequently many faculty members disliked him for his top-down management style.[137] The administration sent out ballots in 1989, and the proposed changes passed, with very slim margins.[137] The restructuring took effect in January 1990. While Crecine was seen in a poor light at the time, the changes he made are considered visionary. In January 1994, Crecine resigned.[137][139] According to historian August Geibelhaus, "There was controversy in every step. Management fought this, because they were the big losers... Crecine was under fire."[137]

Georgia Tech's first campus outside of the United States, Georgia Tech Lorraine

Georgia Tech's first campus outside of the United States, Georgia Tech Lorraine

In October 1990, Tech's first overseas campus, Georgia Tech Lorraine (GTL), opened.[55][140] It is a non-profit corporation operating under French law. GTL primarily focuses on graduate education, sponsored research, and an undergraduate summer program. In 1997, GTL was sued under Toubon Law because the course descriptions on its internet site were not provided in French; these course descriptions constituted an advertisement for this private college and thus fell under the Toubon Law.[141] The case was dismissed on a technicality, though the GTL site now offers course descriptions in English, French and German.[142]

John Patrick Crecine was instrumental in securing the 1996 Summer Olympics for Atlanta. A dramatic amount of construction occurred, creating most of what is now considered "West Campus" in order for Tech to serve as the Olympic Village.[143] The Undergraduate Living Center, Fourth Street Apartments, Sixth Street Apartments, Eighth Street Apartments, Hemphill Apartments, and Center Street Apartments housed athletes and journalists. The Georgia Tech Aquatic Center was built for swimming events, and the Alexander Memorial Coliseum was renovated.[55][143]

Modern history

- Includes the administrations of G. Wayne Clough (1994–2008) and George P. "Bud" Peterson (2009-present)

In 1994, G. Wayne Clough became the first Tech alumnus to serve as the President of the Institute, and was in office during the 1996 Summer Olympics. In 1998, he separated the Ivan Allen College of Management, Policy, and International Affairs into the Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts and returned the College of Management to "College" status.[137][144][145][146] During his tenure, research expenditures have increased from $212 million to $425 million, enrollment has increased from 13,000 to 18,000, Tech received the Hesburgh Award,[147][148] and Tech's U.S. News & World Report rankings have steadily improved.[149][150][151]

President Emeritus G. Wayne Clough and current Georgia Tech president G. P. "Bud" Peterson standing in front of the Ramblin' Wreck on the site of the Clough Undergraduate Learning Commons at its groundbreaking on April 5, 2010.

President Emeritus G. Wayne Clough and current Georgia Tech president G. P. "Bud" Peterson standing in front of the Ramblin' Wreck on the site of the Clough Undergraduate Learning Commons at its groundbreaking on April 5, 2010.

Clough's tenure especially focused on a dramatic expansion and modernization of the institute. Coinciding with the rise of personal computers, computer ownership became mandatory for all students in 1997.[152] In 1998, Georgia Tech was the first university in the Southeastern United States to provide its fraternity and sorority houses with internet access.[153] A campus Local Area Wireless/Walkup Network (LAWN) was established in 1999, and now covers most of campus.[154]

In 1999, Georgia Tech began offering local degree programs to engineering students in Southeast Georgia, and in 2003 established a physical campus in Savannah, Georgia, called Georgia Tech Savannah.[155][156] Clough's administration has also focused on improved undergraduate research opportunities and the creation of an "International Plan" degree option that requires students to spend two terms abroad and take internationally focused courses.[157][158][159][160]

The Technology Square Research Building is part of Technology Square, one of the largest single expansions in the Institute's history.

The Technology Square Research Building is part of Technology Square, one of the largest single expansions in the Institute's history.

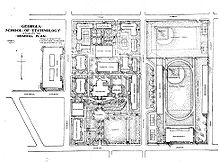

A "Master Plan" for the physical growth and development of the institute has existed since 1912,[161] and has seen significant revisions in 1952, 1965, 1991, 1997, and 2002.[161][162][163][164][165] The latter two of those major revisions have been under Clough's guidance. While Clough was in office, around $1 billion was spent on expanding or improving the campus. These projects include the construction of the Manufacturing Related Disciplines Complex,[166] 10th and Home, Tech Square, The Biomedical Complex,[167] the completion and subsequent renovations of several west campus dorms,[163] the Student Center renovation, the expanded 5th Street Bridge,[163][168] the Georgia Tech Aquatic Center's renovation into the CRC, the new Health Center,[169] the Klaus Advanced Computing Building,[163] the Molecular Science and Engineering Building,[163][168] and the Nanotechnology Research Center.[168]

The school has also taken care to maintain its Historic District, with several projects dedicated to the preservation or improvement of Tech Tower, the school's first and oldest building and its primary administrative center. As part of Phase I of the Georgia Tech Master Plan of 1997, the area was made more pedestrian-friendly with the removal of access roads and the addition of landscaping improvements, benches, and other facilities.[170] The National Register of Historic Places has listed the Georgia Tech Historic District since 1978.[171][172] In the 2007 "Best of Tech" issue of The Technique, students voted "construction" as Georgia Tech's worst tradition.[173]

On March 15, 2008, Clough was appointed to lead the Smithsonian Institution, effective July 1, 2008.[174] Dr. Gary Schuster, Tech's Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs, was named Interim President, effective July 1, 2008.[175] On February 9, 2009, George P. "Bud" Peterson, chancellor of the University of Colorado at Boulder was named the finalist of the presidential search.[176] On April 20, 2010, Georgia Tech was invited to join the Association of American Universities, the first new member institution in nine years.[177]

See also

- History of the Georgia Tech Research Institute

- Georgia Institute of Technology Historic District

- Georgia Tech traditions

- History of Atlanta

- History of Georgia (U.S. state)

References

- ^ Lenz, Richard J. (November 2002). "Surrender Marker, Fort Hood, Change of Command Marker". The Civil War in Georgia, An Illustrated Travelers Guide. Sherpa Guides. http://sherpaguides.com/georgia/civil_war/atlanta/westview_area.html. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Wallace, Robert (1969). Dress Her in WHITE and GOLD: A biography of Georgia Tech. Georgia Tech Foundation.

- ^ a b c d "The Hopkins Administration, 1888-1895". "A Thousand Wheels are set in Motion": The Building of Georgia Tech at the Turn of the 20th Century, 1888-1908. Georgia Institute of Technology. http://www.library.gatech.edu/gtbuildings/hopkins.htm. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ a b c d "The George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering". The American Society of Mechanical Engineers. http://files.asme.org/ASMEORG/Communities/History/Landmarks/1293.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Combes, Richard (1992) (PDF). Origins of Industrial Extension: A Historical Case Study. School of Public Policy, Georgia Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on September 1, 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20060901140557/http://www.cherry.gatech.edu/sim/refs/combes.pdf. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- ^ a b Brittain, James E.; Robert C. McMath, Jr. (April 1977). "Engineers and the New South Creed: The Formation and Early Development of Georgia Tech". Technology and Culture (Johns Hopkins University Press) 18 (2): 175–201. doi:10.2307/3103955. JSTOR 3103955.

- ^ a b c d e "A Walk Through Tech's History". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine Online (Georgia Tech Alumni Association). Summer 2004. http://gtalumni.org/Publications/magazine/sum04/article1.html. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ a b Georgia, (1885). Acts and resolutions of the General Assembly of the State of Georgia, 1884-85. State of Georgia. http://books.google.com/?id=deYXAAAAYAAJ&lpg=PA50&dq=georgia%20general%20assembly%201885&pg=PA69#v=onepage&q=georgia%20general%20assembly%201885. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ a b Mell, P.H., Jr. (1895). "CHAPTER XIX. Efforts Towards Completing the Technological School as a Department of the University of Georgia". Life of Patrick Hues Mell. Baptist Book Concern. http://www.founders.org/library/mell_life/chap19.html. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ Reed, Wallace Putname (1889). History of Atlanta, Georgia, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of Some of Its Prominent Men and Pioneers. Syracuse, NY: D. Mason & Co.. pp. 89–92.

- ^ a b Prospectus. Georgia School of Technology. 1888. http://www.space.gatech.edu/danshiki/Tower/Prospectus.html. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ^ "Quick Facts". Fact Book 2006. Georgia Institute of Technology. http://www.irp.gatech.edu/apps/factbook/?page=5. Retrieved 2007-11-08.

- ^ McMath, p.62

- ^ a b Faculty Handbook. Georgia Institute of Technology Office of Faculty Career Development Services. April 2007. p. 2. http://www.academic.gatech.edu/handbook/Georgia_Institute_of_Technology_-_Faculty_Handbook_April2007.pdf. Retrieved 2007-05-29.

- ^ "GT Buildings: GTVA-UKL999-A". http://www.library.gatech.edu/gtbuildings/GTVA-UKL999-A.htm. Retrieved 2007-01-29.

- ^ "William H. Glenn". Georgia Tech History Digital Portal. Georgia Tech Library. http://history.library.gatech.edu/items/show/1256. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McMath, Robert C.; Ronald H. Bayor, James E. Brittain, Lawrence Foster, August W. Giebelhaus, and Germaine M. Reed. Engineering the New South: Georgia Tech 1885-1985. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press.

- ^ Byrd, Joseph (Spring 1992). "From Civil War Battlefields to the Moon: Leonard Wood". Tech Topics (Georgia Tech Alumni Association). Archived from the original on February 9, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070209190821/http://gtalumni.org/StayInformed/techtopics/spr92/FOW.html. Retrieved 2007-03-12.

- ^ a b Cromartie, Bill (2002) [1977]. Clean Old-fashioned Hate: Georgia Vs. Georgia Tech. Strode Publishers. ISBN 09-3252-064-2.

- ^ Nelson, Clark (2004-11-19). "For Tech fans, victory against UGA means far more than ordinary win". The Technique. Archived from the original on February 20, 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20060220143046/http://www.nique.net/issues/2004-11-19/sports/2. Retrieved 2007-05-17.

- ^ a b c d e "Georgia Tech Traditions". RamblinWreck.com. Georgia Tech Athletic Association. http://ramblinwreck.cstv.com/trads/geot-trads.html. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- ^ Cutter, H. D.. "An Early History of Georgia Tech". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine Online (Georgia Tech Alumni Association). http://gtalumni.org/Publications/magazine/spr98/history.html. Retrieved 2007-06-13.

- ^ a b Stevens, Preston (Winter 1992). "The Ramblin' Wreck from Georgia Tech". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine Online (Georgia Tech Alumni Association). http://gtalumni.org/Publications/magazine/win92/wreck.html. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ a b c "Inventory of the Georgia Tech Songs Collection, 1900-1953". Georgia Tech Archives and Records Management. http://www.library.gatech.edu/archives/finding-aids/display/xsl/UA318. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ a b c "Department History". Music Department. Georgia Tech College of Architecture. Archived from the original on April 9, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070409120103/http://www.coa.gatech.edu/music/about_us/history.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-05.

- ^ "Coast Survey Song". NOAA History. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.history.noaa.gov/art/cssong.html. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ^ a b Edwards, Pat (2000-08-25). "Fight Songs". The Technique. Archived from the original on November 13, 2004. http://web.archive.org/web/20041113073838/http://nique.net/issues/2000-08-25/online+exclusives/11. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ^ Lange, Scott (1998-02-06). "'To hell' with it: Diversity movement talks of change in Georgia Tech song". The Technique. http://technique.library.gatech.edu/issues/winter1998/feb6/news1.html. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ McMath, p.60

- ^ a b "The Georgia Tech Editorial Staff". Georgia Tech Archives Finding Aids. Georgia Tech Library. http://video.library.gatech.edu/cgi-bin/Griffin/griffin.pl?showpic=GP569&lastpicnum=570&search=&fieldtype=key&dispic=yes. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "The Technique". 1911-11-17. http://smartech.gatech.edu/dspace/bitstream/1853/12810/5/technique_v1i1.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-03.[dead link]

- ^ "Staff Manual and Style Guide". The Technique. Archived from the original on January 12, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070112101030/http://www.nique.net/staffmanual/intro-administration.pdf. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ^ a b "ANAK: General History". http://cyberbuzz.gatech.edu/anak/history.html. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ^ Shaw, Jody (2002-08-23). "What is the Technique?". The Technique (Georgia Tech Student Publications). Archived from the original on January 14, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070114085637/http://www.nique.net/issues/2002-08-23/news/1. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ a b "Biographies of the Early Presidents". Inventory of the Early Presidents Collection, 1879-1957 (bulk 1930-1950). Georgia Tech Archives & Records Management. http://www.library.gatech.edu/archives/finding-aids/display/xsl/UA004. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ a b ""Splendid Growth" - The Textile Educational Enterprise at Georgia Tech". Georgia Institute of Technology Library. http://www.library.gatech.edu/gtbuildings/french/growth.htm. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ "Polymer, Textile and Fiber Engineering: History". Georgia Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070211210300/http://www.development.gatech.edu/colleges-schools/engineering/textile-fiber/. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- ^ Kaddi, Chanchala (2005-09-30). "French Building has unique history, old world flavor". The Technique. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070929133350/http://www.nique.net/issues/2005-09-30/opinions/7. Retrieved 2007-03-16.

- ^ McMath, p.71

- ^ McMath, p.77

- ^ McMath, p.92

- ^ "The Hall Administration, 1895-1905". "A Thousand Wheels are set in Motion" - The Building of Georgia Tech at the Turn of the 20th Century, 1888-1908. Georgia Tech Library and Information Center. http://www.library.gatech.edu/gtbuildings/hall.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ Edwards, Pat (1998-01-16). "Ramblins: Hall handed down stiff penalty for senior prank". The Technique. http://technique.library.gatech.edu/issues/winter1998/jan16/campuslife7.html. Retrieved 2007-05-20.

- ^ McMath, p.96

- ^ a b McMath, p.102

- ^ "Lyman Hall Chemistry Building". "A Thousand Wheels are set in Motion" - The Building of Georgia Tech at the Turn of the 20th Century, 1888-1908. Georgia Tech Library and Information Center. http://www.library.gatech.edu/gtbuildings/lyman.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-09.

- ^ "Lyman Hall". Campus Map. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. http://gtalumni.org/campusmap/bldngmodel.php?id=29A. Retrieved 2007-03-26.

- ^ a b Selman, Sean (2002-03-27). "Presidential Tour of Campus Not the First for the Institute". A Presidential Visit to Georgia Tech (Georgia Institute of Technology). Archived from the original on September 4, 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20060904024117/http://www.gatech.edu/presidential-visit/presidential-history.html. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ "One Hundred Years Ago Was Eventful Year at Tech". BuzzWords (Georgia Tech Alumni Association). 2005-10-01. http://gtalumni.org/buzzwords/oct05/article389.html. Retrieved 2006-12-30.

- ^ a b Edwards, Pat (1999-10-15). "Students build first stands at Grant Field". The Technique. http://dev.nique.gatech.edu/issues/1999-10-15/campus%20life/6. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ^ McMath, p.111

- ^ McMath, p.155

- ^ "Freeman is Head of Tech Alumni; High Praise Is Given Leaders in Recent Drive for $5,000,000 Fund for Big Institution". The Atlanta Constitution (Atlanta, GA): p. 1. June 14, 1921. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/ajc_historic/access/516211722.html?dids=516211722:516211722&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:AI. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- ^ McMath, p.123

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Tech Timeline". Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Archived from the original on December 23, 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20061223161821/http://gtalumni.org/Publications/timeline/. Retrieved 2007-03-27.

- ^ a b c "Underground Degrees". Tech Topics (Georgia Tech Alumni Association). Fall 1997. Archived from the original on January 14, 2005. http://web.archive.org/web/20050114055747/http://www.gtalumni.org/StayInformed/techtopics/fall97/degrees.html. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ^ a b Cuneo, Joshua (2003-04-11). "Female faculty, staff offer professional perspectives". Archived from the original on January 10, 2006. http://web.archive.org/web/20060110222125/http://www.nique.net/issues/2003-04-11/focus/3. Retrieved 2007-03-17.

- ^ a b McMath, p.125

- ^ McMath, p.116

- ^ "Georgia Football records 1915-1919". College Football Data Warehouse. http://www.cfbdatawarehouse.com/data/div_ia/sec/georgia/yearly_results.php?year=1915. Retrieved 2007-04-27.

- ^ a b McMath, p.143

- ^ a b Van Brimmer, Adam (2006) [2006]. Stadium Stories: Georgia Tech Yellow Jackets. Atlanta, Georgia: Globe Pequot. pp. 170–175. ISBN 978-0762740208.

- ^ a b McMath, p.144

- ^ a b c Burns, G. Frank. "222-0: The Story of The Game of the Century". http://www2.cumberland.edu/about/gotc/gamestory.html. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ^ "PLAY-BY-PLAY: GEORGIA TECH 222, CUMBERLAND 0". 1916-10-07. http://www2.cumberland.edu/about/gotc/pbp.html. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ^ "Tech Timeline: 1910s". Tech Traditions. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071016201916/http://gtalumni.org/Publications/timeline/1910s.html. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ^ McMath, p.153

- ^ a b McMath, p.154

- ^ a b McMath, p.159

- ^ McMath, p.165

- ^ "The Sky's the Limit: Guggenheim Award established School of Aeronautics". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine. Georgia Tech Alumni Association. Fall 2003. Archived from the original on October 28, 2005. http://web.archive.org/web/20051028091432/http://gtalumni.org/StayInformed/magazine/fall03/article3.html. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ a b c "Obituaries". TIME. 1953-07-13. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,806727,00.html. Retrieved 2007-06-01.

- ^ "Institution Details: Georgia Institute of Technology". Commission on Colleges Membership Directory. Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. http://www.sacscoc.org/details.asp?instid=33760. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ McMath, p.167

- ^ "Wrong Way Reigels". Georgia Tech Alumni Magazine (Georgia Tech Alumni Association). Spring 1998. Archived from the original on December 27, 2005. http://web.archive.org/web/20051227105544/http://gtalumni.org/news/magazine/spr98/div04.html. Retrieved 2007-09-15.

- ^ a b c McMath, p.186

- ^ McMath, p.175

- ^ McMath, p.176

- ^ McMath, p.177

- ^ McMath, p.178

- ^ McMath, p.180

- ^ "History of Georgia State University". Georgia State University Library. 2003-10-06. http://www.library.gsu.edu/spcoll/pages/pages.asp?ldID=105&guideID=549&ID=3670. Retrieved 2007-03-15.