- Fahrenheit 9/11

-

Fahrenheit 9/11

Promotional poster by Lisa Sandler for Miramax FilmsDirected by Michael Moore Produced by - Michael Moore

- Jim Czarnecki

- Kathleen Glynn

- Harvey Weinstein

- Bob Weinstein

Written by Michael Moore Starring Michael Moore Distributed by - Lions Gate Films

- IFC Films

- Dog Eat Dog Films

Release date(s) May 17, 2004 (Sundance)

June 25, 2004 (United States)Running time 122 minutes Country United States Language English Budget $6 million Box office $222,446,882[1] Fahrenheit 9/11 is a 2004 documentary film by American filmmaker and political commentator Michael Moore. The film takes a critical look at the presidency of George W. Bush, the War on Terror, and its coverage in the news media. The film is the highest grossing documentary of all time.[2]

In the film, Moore contends that American corporate media were "cheerleaders" for the 2003 invasion of Iraq and did not provide an accurate or objective analysis of the rationale for the war or the resulting casualties there. The film generated intense controversy, including some disputes over its accuracy. Moore has responded by documenting his sources.

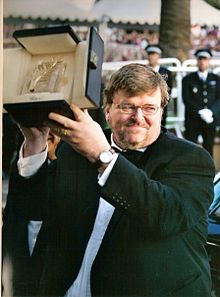

The film debuted at the 2004 Cannes Film Festival in the documentary film category and received a 20 minute standing ovation, among the longest standing ovations in the festival's history. The film was also awarded the Palme d'Or (Golden Palm),[3] the festival's highest award.

The film had a general release in the United States and Canada on June 23, 2004. It has since been released in 42 more countries. By January 2005, the film had grossed nearly $120 million in U.S. box office and over $220 million worldwide,[1] an unprecedented amount for a political film. Sony reported first-day DVD sales of two million copies, again a new record for the genre.[4][dead link]

The title of the film alludes to Ray Bradbury's 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451, a dystopian view of the future United States, analogizing the autoignition temperature of paper with the date of the September 11 attacks; the film's tagline is "The Temperature at Which Freedom Burns."

Contents

Financing, pre-release, and distribution

Originally planned to be financed by Mel Gibson's Icon Productions (which planned to give Michael Moore eight figures in upfront cash and potential backend),[5] Fahrenheit 9/11 was later picked up by Miramax Films and Wild Bunch in May 2003 after Icon Productions had abruptly dropped the financing deal it made.[6] Miramax had earlier distributed another film for Moore, The Big One, in 1997.

At that time, Disney was the parent company of Miramax. According to the book DisneyWar, Disney executives didn't know that Miramax agreed to finance the film until they saw a posting on the Drudge Report. Afterward, Michael Eisner (who was the CEO of Disney at that time) called Harvey Weinstein (who was the co-chairman of Miramax at that time) and required him to drop the film. In addition, Disney sent two letters to Weinstein demanding Miramax drop the film. Weinstein felt Disney had no right to block them from releasing Fahrenheit 9/11 since the film's $6 million budget was well below the level that Miramax needed to seek Disney's approval, and it wouldn't be rated NC-17.[7] But Weinstein was in contract negotiations with Disney, so he offered compromises and said that he would drop the film if Disney didn't like it.[7] Disney responded by having Peter Murphy send Weinstein a letter stating that the film's $6 million budget was only a bridge financing and Miramax would sell off their interest in the movie to get those $6 million back; according to the same letter, Miramax was also expected to publicly state that they wouldn't release the film.[7]

After Fahrenheit 9/11 was nearly finished, Miramax held several preview screenings for the film; in the screenings, the film was "testing through the roof."[8] Afterward, Harvey Weinstein said to Michael Eisner that Fahrenheit 9/11 was finished, and Eisner was surprised by the fact that Miramax had continued making the film.[8] Weinstein asked several Disney executives (including Eisner) to watch the film, but all of them declined; Disney stated again that Miramax would not release the film, and Disney also accused Weinstein of hiding Fahrenheit 9/11 by keeping it off production reports.[8] Finally, Disney sent their production vice president Brad Epstein to watch Fahrenheit 9/11 on April 24, 2004.[8] According to Weinstein, Epstein said to Weinstein that he liked the film; but according to the report Epstein sent to Disney board, Epstein clearly criticized it.[8] Afterward, Eisner told Weinstein that Disney board decided not to allow Miramax to release the film.[8] Weinstein was furious and he asked George J. Mitchell (who was the chairman of Disney at that time) to see the film, but Mitchell declined.[8] Later, Weinstein asked lawyer David Boies to help him find a solution.[8]

The New York Times reported about Disney's decision on May 5, 2004.[9] Disney stated that both Moore's agent (Ari Emanuel) and Miramax were advised in May 2003 that Miramax would not be permitted to distribute the film. Disney representatives claim that Disney has the right to veto any Miramax film if it appears that their distribution would be counterproductive to the interests of the company. Disney had blocked Miramax from releasing two films before: Kids and Dogma.[10]

An unnamed Disney executive said that the film was against Disney's interests not because of government business dealings, but because releasing it would risk being "dragged into a highly charged partisan political battle" and alienating customers. Emanuel stated that Disney chief executive Michael Eisner requested that he back out of the Miramax deal, expressing concerns about political fallout from conservative politicians, especially regarding tax breaks given to Disney properties in Florida (e.g., Walt Disney World), where Jeb Bush is governor. Disney also has financial ties to members of the Saudi royal family,[11] who were represented unfavorably in the film. Moore admitted later in a CNN interview that Disney had told him they did not want the film a year earlier, however, he had been advised by representatives that Miramax would continue to fund filming. Seemingly in approval, Disney continued to fund Fahrenheit 9/11 via Miramax throughout the remaining year of production.

Due to these difficulties, distribution for the film was first secured in numerous countries outside the U.S. On May 28, 2004, after more than a week of talks, Disney announced that Miramax film studio founders Harvey and Bob Weinstein had personally acquired the rights to the documentary from Walt Disney Co. after Disney declined to distribute it. The Weinsteins agreed to repay Disney for all costs of the film to that point, estimated at around $6 million. They also agreed to be responsible for all costs to finish the film and all marketing costs not paid by any third-party film distributors.[12] A settlement between the Weinsteins and Disney was also reached so that 60% of the film's profit would be donated to charity.[13]

Later, The Weinsteins established Fellowship Adventure Group to handle the distribution of this film. Fellowship Adventure Group joined forces with Lions Gate Entertainment (which had released two other Miramax-financed films O and Dogma)[14] and IFC Films to release this film in the United States theatrically. (Later, Fellowship Adventure Group also handled this film's United States home video distribution via Columbia TriStar Home Entertainment). Moore stated that he was "grateful to them now that everyone who wants to see it will now have the chance to do so.[15]

After being informed that the film had been rated R by the Motion Picture Association of America, Moore appealed the decision, hoping to obtain a PG-13 rating instead. (The R rating requires anyone under the age of 17 to be accompanied by a parent or adult guardian.) Moore's lawyer, former Governor of New York, Mario Cuomo, was not allowed to attend the hearing. The appeal was denied on June 22, 2004, and Cuomo contended that it was because he had been banned from the hearing. Some theaters chose to defy the MPAA and allow unchaperoned teenagers to attend screenings. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops' Office for Film and Broadcasting gave the film an A-III rating, meaning that it was, in their judgment, "morally unobjectionable for adults" (this is the mildest rating typically given by the organization to motion pictures that are rated R by the MPAA).[16] Moore commented that he was willing to "sneak anyone in".[dead link]

Content summary

The movie begins by suggesting that friends and political allies of George W. Bush at Fox News Channel tilted the election of 2000 by prematurely declaring Bush the winner. It then suggests the handling of the voting controversy in Florida constituted election fraud.

The film then segues into the September 11 attacks, with the screen going black and the film relying solely on sounds to illustrate the chaos on that day. When the film resumes, it continues with scenes of the bystanders, survivors, and falling debris of the World Trade Center. Moore notes that Bush was informed of the first plane hitting the World Trade Center on his way to an elementary school. Bush is then shown sitting in a Florida classroom with kids. When told that a second plane has hit the World Trade Center and that the nation is "under attack" Bush continues reading The Pet Goat to the kids, and Moore notes that he continued reading for nearly seven minutes.

The film then discusses the causes and aftermath of the September 11 attacks, including the 2003 invasion of Iraq. Moore then discusses the complex relationships between the U.S. government, the Bush family, the bin Laden family, the Saudi Arabian government, and the Taliban, which span over three decades. Moore alleges that the United States Government evacuated 24 members of the bin Laden family on a secret flight shortly after the attacks, without subjecting them to any form of interrogation. At the time, all other domestic and international civilian air traffic within the United States was grounded.

Moore moves on to examine George W. Bush's Air National Guard service record. Moore contends that Bush's dry-hole oil well attempts were partially funded by the Saudis and by the bin Laden family through the intermediary of James R. Bath. Moore alleges that these conflicts of interest suggest that the Bush administration is not working for the best interests of Americans. The movie continues by suggesting ulterior motives for the War in Afghanistan, including a natural gas pipeline through Afghanistan to the Indian Ocean.

Moore alleges that the Bush administration induced a climate of fear among the American population through the mass media. Moore then describes purported anti-terror efforts, including government infiltration of pacifist groups and other events, and the signing of the USA PATRIOT Act, which vastly expands government powers. After finding out that members of Congress do not read most of the bills that they vote on, including the USA PATRIOT Act, Moore drives through Washington D.C. in an ice cream truck using the external speaker to read the PATRIOT Act to them.

The documentary then turns to the subject of the Iraq War, comparing the lives of the Iraqis before and after the invasion. The citizens of Iraq are shown to be living relatively happy lives prior to the country's invasion by the U.S. military. The film also takes pains to demonstrate war cheerleading in the U.S. media and general bias of journalists, with quotes from news organizations and embedded journalists. The film then shows Bush's moment of "Mission Accomplished" on board the USS Abraham Lincoln. The film alternates between media reports of increased casualties in Iraq and Bush's comment to "Bring 'em on", referring to the Iraqi insurgency.

The film then shifts its focus to Moore's hometown, Flint, Michigan. The economically hard-hit town's low-income neighborhoods were the prime target of military recruiters. A recruiter named Raymond Plouhar is introduced (he was later killed in Iraq), as he and another marine recruiter track people down in a parking lot of a mall. The film introduces Lila Lipscomb, a woman presented as the proud mother of a U.S. serviceman. She expresses her strong sense of patriotism and support for the men and women in uniform.

Moore suggests that, because the war was based on a lie, atrocities will occur, and shows footage depicting U.S. abuse of prisoners.

Later in the film, Lipscomb reappears with her family after hearing of the death of her son, Sgt. Michael Pedersen, who was killed on April 2, 2003, in Karbala. Anguished and tearful, she begins to question the purpose of the war. Because Moore was tired of seeing people like Lila Lipscomb suffer, and after discovering that only one member of Congress has a child serving in Iraq, he distributes armed services enrollment information to various members of Congress and suggests that they enlist their children.

Tying together several themes and points, Moore compliments those serving in the U.S. military. He claims that the lower class of America are always the first to join the army and defend the nation, so that the people better off do not have to. He states that those valuable troops should not be sent to risk their lives unless it is absolutely necessary. The film ends with a clip of George W. Bush stumbling through his infamous "Fool me once" quote. The credits roll while Neil Young's "Rockin' in the Free World" plays.

Moore dedicated the film to his friend who was killed in the World Trade Center attacks and to those servicemen and women from Flint, Michigan that have been killed in Iraq. The film is also dedicated to "countless thousands" of civilian victims of war as a result of United States military activities in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Film release and box office

Alternate Fahrenheit 9/11 poster

Alternate Fahrenheit 9/11 poster

The film was released theatrically by The Fellowship Adventure Group through a distribution arrangement with Lions Gate Entertainment. The Fellowship Adventure Group was formed by Bob and Harvey Weinstein specifically for the release of Fahrenheit 9/11. On its opening weekend of June 25 – June 27, the film generated box-office revenue of $23.9 million in the U.S. and Canada, making it the weekend's top-grossing film, despite having been screened in only 868 theaters (many of the weekend's other top movies played on over 2,500 screens). Its opening weekend earned more than the entire U.S. theatrical run of any other feature-length documentary (including Moore's previous film, Bowling for Columbine). The film was released in the UK on July 2, 2004 and in France on July 7, 2004.[17]

During the weekend of July 24, 2004, the film passed the $100 million mark in box-office receipts.[18]

Moore credited part of this success to the efforts of conservative groups to pressure theaters not to run the film, conjecturing that these efforts backfired by creating publicity. There were also efforts by liberal groups such as MoveOn.org (who helped promote the film) to encourage attendance in order to defy their political opponents' contrary efforts.[19]

Fahrenheit 9/11 was screened in a number of Middle Eastern countries, including the United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, and Egypt, but was immediately banned in Kuwait. "We have a law that prohibits insulting friendly nations," said Abdul-Aziz Bou Dastour of the Information Ministry.[20][21] The film was not shown in Saudi Arabia as public movie theaters are not permitted. The Saudi ruling elite subsequently launched an advertising campaign spanning nineteen US cites to counter criticism partly raised in the film.[22]

The film was shown in Iran, an anomaly in a nation in which American films had been banned since the Iran hostage crisis in 1979. Iranian film producer and human rights activist Banafsheh Zand-Bonazzi communicated with Iranians who saw the film, and claimed that it generated a pro-American response.[23]

In Cuba, bootlegged versions of the film were shown in 120 theaters, followed by a prime-time television broadcast by the leading state-run network. It had been widely reported that this might affect its Oscar eligibility. However, soon after that story had been published, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences issued a statement denying this, saying, "If it was pirated or stolen or unauthorized we would not blame the producer or distributor for that."[24] In addition, Wild Bunch, the film's overseas distributor for Cuba, issued a statement denying a television deal had been struck with Cuban Television. The issue became moot, however, when Moore decided to forgo Oscar eligibility in favor of a pay-per-view televising of the film on November 1, 2004.

DVD release

Fahrenheit 9/11 was released to DVD and VHS on October 5, 2004, an unusually short turnaround time after theatrical release. In the first days of the release, the film broke records for the highest-selling documentary ever. About two million copies were sold on the first day.[25]

A companion book, The Official Fahrenheit 9/11 Reader, was released at the same time. It contains the complete screenplay, documentation of Moore's sources, audience e-mails about the film, film reviews, articles, and political cartoons pertaining to the film. The DVD also contained some additional footage.[26]

Initial television presentations

The two-hour film was planned to be shown as part of the three-hour "The Michael Moore Pre-Election Special" on iN DEMAND, but iN DEMAND backed out in mid-October. Moore later arranged for simultaneous broadcasts on November 1, 2004 at 8:00 p.m. (EST) on Dish Network, TVN, and the Cinema Now website and material prepared for "The Michael Moore Pre-Election Special" was incorporated into "Fahrenheit 9/11: A Movement in Time", which aired that same week on The Independent Film Channel.

The movie was also shown on basic cable television in Germany and Austria on November 1, 2004 and November 2, 2004. In the UK, the film was shown on Channel 4 on January 27, 2005. In Hungary, it was shown on RTL Klub, a commercial channel, on September 10, 2005, on m1, one of the national channels, on August 13, 2006, on m2, the other national channel, on September 1, 2006. In Denmark, it was shown on Danmarks Radio (normally referred to as just DR), which is Denmark's national broadcasting corporation, on April 11, 2006. In Norway, it was shown on NRK, the national broadcasting corporation, on August 27, 2006. The film was screened in New Zealand on September 9, 2006 on TV ONE, a channel of TVNZ. The next day, the Dutch network Nederland 3 aired the film. In Belgium, it was shown on Kanaal 2 on October 12, 2006. In Brazil, it aired on October 10, 2008 on TV Cultura, the São Paulo public broadcasting network.

Reception

Critical reception

The film was received positively by critics. It received a 84% Fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 221 reviews.[27] It also received a score of 67 (generally favorable) on Metacritic, based on 43 reviews.[28] The consensus according to Rotten Tomatoes is that the documentary presents a one-sided debate, but is worth watching for the debates that it stirs.[27]

Film critic Roger Ebert, who gave the documentary three and a half stars out of four, says that the film "is less an expose of George W. Bush than a dramatization of what Moore sees as a failed and dangerous presidency." In the film, Moore presents footage of Vice President Al Gore presiding over the event that would officially anoint Bush as president, the day that a joint session of the House of Representatives and the Senate would certify the election results. "Moore brings a fresh impact to familiar material by the way he marshals his images", says Ebert.

Entertainment Weekly put it on its end-of-the-decade, "best-of" list, saying, "Michael Moore's anti-Bush polemic gave millions of frustrated liberals exactly what they needed to hear in 2004--and infuriated just about everyone else. Along the way, it became the highest-grossing documentary of all time."[29]

Commercial reception

The film grossed over $222 million, becoming the highest-grossing documentary of all time.[1]

Awards

Palme d'Or

In April 2004, the film was selected to compete for the Palme d'Or at the 57th Cannes Film Festival. After its first showing in Cannes in May 2004, the film received a 15–20 minute standing ovation; Harvey Weinstein, whose Miramax Films funded the film, said, "It was the longest standing ovation I've seen in over 25 years."[30][dead link][31]

On May 22, 2004, the film was awarded the Palme d'Or.[3] It was the first documentary to win that award since Jacques Cousteau and Louis Malle's The Silent World in 1956. Just as his much-publicized Oscar acceptance speech, Moore's speech in Cannes included some political statements:[32]

I can't begin to express my appreciation and my gratitude to the jury, the Festival, to Gilles Jacob, Frémaux, Bob and Harvey at Miramax, to all of the crew who worked on the film. [...] I have a sneaking suspicion that what you have done here and the response from everyone at the festival, you will assure that the American people will see this film. I can't thank you enough for that. You've put a huge light on this and many people want the truth and many want to put it in the closet, just walk away. There was a great Republican president who once said, if you just give the people the truth, the Republicans, the Americans will be saved. [...] I dedicate this Palme d'Or to my daughter, to the children of Americans and to Iraq and to all those in the world who suffer from our actions.

Some conservatives in the United States, such as Jon Alvarez of FireHollywood, commented that such an award could be expected from the French.[33] Moore had remarked only days earlier that: "I fully expect the Fox News Channel and other right-wing media to portray this as an award from the French. [...] There was only one French citizen on the jury. Four out of nine were American. [...] This is not a French award, it was given by an international jury dominated by Americans."[34] The jury was made up of four North Americans, four Europeans, and one Asian.[citation needed]

He also responded to suggestions that the award was political: "Quentin [Tarantino] whispered in my ear, 'We want you to know that it was not the politics of your film that won you this award. We are not here to give a political award. Some of us have no politics. We awarded the art of cinema, that is what won you this award and we wanted you to know that as a fellow filmmaker.'"[35] In comments to the prize-winning jury in 2005, Cannes director Gilles Jacob said that panels should make their decision based on filmmaking rather than politics. He expressed his opinion that though Moore's talent was not in doubt, "it was a question of a satirical tract that was awarded a prize more for political than cinematographic reasons, no matter what the jury said."[36] Interviewed about the decision four years later, Tarantino responded: "As time has gone on, I have put that decision under a microscope and I still think we were right. That was a movie of the moment – Fahrenheit 9/11 may not play the same way now as it did then, but back then it deserved everything it got."[37][dead link]

People's Choice Award

The film won additional awards after its release, such as the People's Choice Awards for Favorite Motion Picture, an unprecedented honor for a documentary.

Golden Raspberry

The film also won four Razzies for its "acting" performances. George W. Bush won Worst Actor, Bush with either Rice or "his pet goat" won Worst Screen Couple, Donald Rumsfeld won Worst Supporting Actor, and Rice and Britney Spears were both nominated for Worst Supporting Actress, with Spears winning the award (for her comments about Bush and the war).[38]

Controversy

The film generated some controversy and criticism after its release shortly before the United States presidential election, 2004. British-American journalist and literary critic Christopher Hitchens contended that Fahrenheit 9/11 contains distortions and untruths.[39] This drew several rebuttals, including an eFilmCritic article and a Columbus Free Press editorial.[40] Former Democratic mayor of New York City Ed Koch, who had endorsed President Bush for re-election, called the film propaganda.[41] In response, Moore published a list of facts and sources for Fahrenheit 9/11 and a document that he says establishes agreements between the points made in his film and the findings of the 9/11 Commission.[42]

Influence on the 2004 presidential election

The film was released in June 2004, less than five months before the 2004 presidential election. Michael Moore, while not endorsing presidential candidate John Kerry, stated in interviews that he hoped "to see Mr. Bush removed from the White House".[43] He also said that he hoped his film would influence the election: "This may be the first time a film has this kind of impact".[43] However, some political analysts did not expect it to have a significant effect on the election. One Republican strategist stated that Moore "communicates to that far-left sliver that would never vote for Bush", and Jack Pitney, a government professor at Claremont McKenna College, suspected that the main effect of the film would be to "turn Bush-haters into bigger Bush-haters."[43] Regardless of whether the film would change the minds of many voters, Moore stated his intention to use it as an organizing tool, and hoped that it would energize those who wanted to see Bush defeated in 2004, increasing voter turnout.[44] Notwithstanding the film's influence and commercial success, George W. Bush was re-elected in 2004.

Lawsuit

In February 2011, Moore sued producers Bob and Harvey Weinstein for US$2.7 million in unpaid profits from the film, stating that they used "Hollywood accounting tricks" to avoid paying him the money.[45] They responded Moore had received US$20 million for the film and that "his claims are hogwash".[45]

References

- ^ a b c "Fahrenheit 9/11". Box Office Mojo. http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=fahrenheit911.htm. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Fernandez, Jay A. (30 May 2008). "Int'l sales brisk for Moore pic". The Hollywood Reporter. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/intl-sales-brisk-moore-pic-112839. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Fahrenheit 9/11 (Fahrenheit 911)". festival-cannes.com. http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/4201423/year/2004.html. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Fahrenheit 9/11 burns records on debut day October 7, 2004[dead link]

- ^ Fleming, Michael (27 March 2003). "Moore tools up for another furor". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117883755.html?categoryid=3&cs=1. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Fleming, Michael (8 May 2003). "Moore's hot-potato '911' docu loses an Icon". Variety. http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117885862.html?categoryid=1742&cs=1. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ a b c Stewart, p.429-430

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stewart, p.519-520

- ^ Rutenberg, Jim (5 May 2004). "Disney Is Blocking Distribution of Film That Criticizes Bush". The New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B01E2DB1E3DF936A35756C0A9629C8B63. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Stuart Miller (16 October 2005). "The ripple effect". Variety. http://www.variety.com/index.asp?layout=variety100&content=jump&jump=general&articleID=VR1117930598. Retrieved 2 October 2011.}}

- ^ Sims, Calvin (2 June 1994). "Rich Saudi Bails Out Disney Unit". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1994/06/02/business/rich-saudi-bails-out-disney-unit.html. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ "Weinstein Brothers buy Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11". ctv.ca. 29 May 2004. http://www.ctv.ca/CTVNews/Entertainment/20040529/moore_documentary_040528/. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Commondreams.org

- ^ Newsweek.com

- ^ Bruce Orwall (2 July 2004). "Big Part of 'Fahrenheit 9/11' Profit Goes to Charity". commondreams.org. http://www.commondreams.org/headlines04/0702-07.htm. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ USCCB.org, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops.

- ^ "Fahrenheit 9/11 - International Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?page=intl&id=fahrenheit911.htm. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ "Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) - Weekend Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?page=weekend&id=fahrenheit911.htm. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ Paul Magnusson (12 July 2004). "Will Fahrenheit 9/11 Singe Bush". BW Online. http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/04_28/c3891087_mz013.htm. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- ^ "Kuwait bans anti-Bush documentary". BBC News. 2 August 2004. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/3527000.stm. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Donna Abu-Nasr (22 August 2004). "Arabs denounce, embrace Fahrenheit". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

- ^ Brian Whitaker (19 August 2004). "Saudis buy ads to counter Fahrenheit 9/11". The Age.

- ^ Banafsheh Zand-Bonazzi (29 September 2004). "Iranian Citizens Trash Fahrenheit 9/11". frontpagemag.com. http://archive.frontpagemag.com/readArticle.aspx?ARTID=11207. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Josh Grossberg (August 3, 2004). "Moore's Cuban Oscar Crisis?". E Online. http://www.eonline.com/News/Items/0,1,14644,00.html. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Brett Sporich (6 October 2004). "'Fahrenheit' Burns Home-Video Sales Records". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 October 2004. http://web.archive.org/web/20041011105455/http://www.reuters.com/newsArticle.jhtml?type=entertainmentNews&storyID=6433900. Retrieved 3 October 11.

- ^ "Fahrenheit 9/11 DVD Features". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 20 September 2004. http://web.archive.org/web/20040920231850/http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/fahrenheit_911/dvd.php?select=1. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Fahrenheit 9/11". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/fahrenheit_911/. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ "Fahrenheit 9/11". Metacritic. http://www.metacritic.com/movie/fahrenheit-911. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Geier, Thom; Jensen, Jeff; Jordan, Tina; Lyons, Margaret; Markovitz, Adam; Nashawaty, Chris; Pastorek, Whitney; Rice, Lynette et al. (11 December 2009). "THE 100 Greatest MOVIES, TV SHOWS, ALBUMS, BOOKS, CHARACTERS, SCENES, EPISODES, SONGS, DRESSES, MUSIC VIDEOS, AND TRENDS THAT ENTERTAINED US OVER THE PAST 10 YEARS". Entertainment Weekly: 74–84.

- ^ 'Fahrenheit' lights fire in Cannes debut, The Hollywood Reporter. May 18, 2004.[dead link]

- ^ Anti-Bush film tops Cannes awards, BBC News Online. May 24, 2004.

- ^ "Palme d'Or to "Fahrenheit 9/11" by Michael Moore". festival-cannes.com. May 23, 2004. http://www.festival-cannes.com/fr/theDailyArticle/43018.html. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Jon Alvarez (28 May 2004). "The French, Michael Moore, and Fahrenheit 9/11". chronwatch.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2004. http://web.archive.org/web/20040815210642/http://www.chronwatch.com/content/contentDisplay.asp?aid=7563. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ A. O. Scott (23 May 2004). "'Fahrenheit 9/11' Wins Top Prize at Cannes". The New York Times.

- ^ "Moore film 'won Cannes on merit'". BBC News. 23 May 2004. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/3740939.stm. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Caroline Briggs (11 May 2005). "'No politics' at Cannes festival". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/4538803.stm. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Hirschberg, Lynn. The Call Back: Quentin Tarantino, T magazine, Summer 2009.[dead link]

- ^ John Wilson (2005). "Halle’s Feline Fiasco CATWOMAN and President’s FAHRENHEIT Blunders Tie for 25th RAZZIE® Dis-Honors". razzies.com. Golden Raspberry Award Foundation. http://www.razzies.com/asp/directory/25thWinners.htm. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Hitchens, Christopher (21 June 2004). "Unfairenheit 9/11: The lies of Michael Moore". Slate.com. http://www.slate.com/id/2102723. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ^ "A defense of Michael Moore and "Fahrenheit 9/11"". blueyonder.co.uk. http://www.overcast.pwp.blueyonder.co.uk/f911/hitch-moore.htm. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ^ Koch, Ed (29 June 2004). "Koch: Moore's propaganda film cheapens debate, polarizes nation". WorldTribune.com. http://www.worldtribune.com/worldtribune/WTARC/2004/guest_koch_6_28.html. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ^ "Film footnotes: Fahrenheit 9/11". MichaelMoore.com. http://www.michaelmoore.com/books-films/facts/fahrenheit-911. Retrieved 5 October 2011.}}

- ^ a b c Kasindorf, Martin; Keen, Judy (25 June 2004). "'Fahrenheit 9/11': Will it change any voter's mind?". USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/news/politicselections/nation/president/2004-06-24-fahrenheit-cover_x.htm. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ^ McNamee, Mike (12 July 2004). "Washington Outlook: Will Fahrenheit 9/11 Singe Bush?". BusinessWeek. http://www.businessweek.com/magazine/content/04_28/c3891087_mz013.htm. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Film-maker Michael Moore sues Weinstein brothers". bbc.co.uk. 9 February 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-12402807. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

Further reading

- Stewart, James B. (2005). DisneyWar. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80993-1.

External links

- Official website

- Fahrenheit 9/11 at the Internet Movie Database

- Fahrenheit 9/11 at AllRovi

- Fahrenheit 9/11 at Box Office Mojo

- Fahrenheit 9/11 at Rotten Tomatoes

Palme d'Or winning films – 2000–present Dancer in the Dark (2000) · The Son's Room (2001) · The Pianist (2002) · Elephant (2003) · Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) · The Child (2005) · The Wind That Shakes the Barley (2006) · 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (2007) · The Class (2008) · The White Ribbon (2009) · Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) · The Tree of Life (2011)

George W. Bush Life

Presidency First term · Second term · Cabinet · Domestic policy · Legislation and programs · Economic policy · Foreign policy · Bush Doctrine · Iraq War · Judicial appointments · Pardons · Presidential library · Efforts to impeachElections Public image Books In fiction Family Laura Bush (wife) · Barbara Pierce Bush (daughter) · Jenna Bush Hager (daughter) · George H. W. Bush (father) · Barbara Bush (mother) · Barney (dog) · Miss Beazley (dog) · India (cat)Michael Moore Films Roger & Me (1989) · Pets or Meat: The Return to Flint (1992) · Canadian Bacon (1995) · The Big One (1998) · Bowling for Columbine (2002) · Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004) · Sicko (2007) · Captain Mike Across America (2007) · Slacker Uprising (2008) · Capitalism: A Love Story (2009)Television Books Downsize This! Random Threats from an Unarmed American (1996) · Adventures in a TV Nation (1998; with Kathleen Glynn) · Stupid White Men ...and Other Sorry Excuses for the State of the Nation! (2002) · Dude, Where's My Country? (2003) · Will They Ever Trust Us Again? (2004) · The Official Fahrenheit 9/11 Reader (2004) · Mike's Election Guide 2008 (2008) · Here Comes Trouble: Stories from My Life (2011)Categories:- 2004 films

- American films

- English-language films

- 2000s documentary films

- American independent films

- American documentary films

- Documentary films about American politics

- Documentary films about the September 11 attacks

- Documentary films about the Iraq War

- Films about Presidents of the United States

- Films about the United States presidential election, 2000

- United States presidential election, 2004 in popular culture

- Films shot in Iraq

- Films directed by Michael Moore

- Palme d'Or winners

- Lions Gate Entertainment films

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.