- Fahrenheit 451

-

Fahrenheit 451

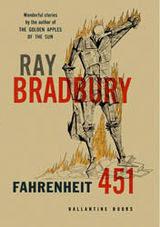

First edition coverAuthor(s) Ray Bradbury Illustrator Joe Pernaciaro Country United States Language English Genre(s) Dystopian novel Publisher Ballantine Books Publication date 1953 Media type Print (hardback and paperback) Pages 179 pp ISBN ISBN 978-0-7432-4722-1 (current cover edition) OCLC Number 53101079 Dewey Decimal 813.54 22 LC Classification PS3503.R167 F3 2003 Fahrenheit 451 is a 1953 dystopian novel by Ray Bradbury. The novel presents a future American society where reading is outlawed and firemen start fires to burn books. Written in the early years of the Cold War, the novel is a critique of what Bradbury saw as issues in American society of the era.[1]

In 1947, Bradbury wrote a short story titled "Bright Phoenix" (later revised for publication in a 1963 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction).[2] Bradbury expanded the basic premise of "Bright Phoenix" into The Fireman, a novella published in the February 1951 issue of Galaxy Science Fiction. First published in 1953 by Ballantine Books, Fahrenheit 451 is twice as long as "The Fireman." A few months later, the novel was serialized in the March, April, and May 1954 issues of Playboy. Bradbury wrote the entire novel on a pay typewriter in the basement of UCLA's Powell Library.

The novel has been the subject of various interpretations, primarily focusing on the historical role of book burning in suppressing dissenting ideas. Bradbury has stated that the novel is not about censorship, but a story about how television destroys interest in reading literature, which leads to a perception of knowledge as being composed of factoids, partial information devoid of context.[3]

François Truffaut wrote and directed a film adaptation of the novel in 1966. At least two BBC Radio 4 dramatizations have also been aired, both of which follow the book very closely.

Contents

Plot summary

The Hearth and the Salamander

On a rainy night while returning from his job, fireman Guy Montag meets his new neighbor Clarisse McClellan, whose free-thinking ideals and liberating spirit force him to question his life, his ideals, and his own perceived happiness. Montag returns home to find his wife Mildred asleep with an empty bottle of sleeping pills. He calls for medical help; two technicians respond by proceeding to suck out Mildred's blood with a machine and insert new blood into her. Their disregard for Mildred forces Montag to question the state of society. Later, he finds out that Clarisse has been killed in a hit and run.

In the following days, while at work with the other firemen ransacking the book-filled house of an old woman before the inevitable burning, Montag accidentally reads a line in one of her books: "Time has fallen asleep in the afternoon sunshine". This prompts him to steal one of the books. The woman refuses to leave her house and her books, choosing instead to light a match and burn herself alive. This act disturbs Montag, who wonders why someone would die for books, which he considers to be without value. Jarred by the woman's suicide, Montag becomes physically ill and calls for sick leave. Fire chief Captain Beatty visits him at home to tell him the history of the firemen. He tells Montag that interest in books declined gradually over several decades as the public embraced mass-marketed new media and a quickening pace of life. Books became despised for their controversial content, and the government outlawed them with little resistance. While they are talking, Mildred feels the book hidden under Montag's pillow and reacts with surprise. Beatty adds casually that all firemen eventually steal a book out of curiosity, but all is well if the book is burned within 24 hours.

After Beatty has left, Montag shows Mildred the books he has hidden in the ventilator of their home. Mildred tries to incinerate the books, however, Montag holds her back and tells her that together they must read the books and decide if they have value. If they do not, he promises the books will be burned and all will return to normal.

The Sieve and the Sand

Montag argues with his wife, Mildred, over the book he has stolen, showing his growing disgust for her and for his society. It is revealed that Montag has, over the course of a year, hidden dozens of books in the ventilation shafts of his own house, and tries to memorize them to preserve their contents, but becomes frustrated that the words seem to simply fall away from his memory. He then remembers a man he had met at one time: Faber, a former English professor. Montag seeks Faber's help. Faber teaches Montag about the importance of literature in its attempt to explain human existence. He gives Montag a green bullet-shaped ear-piece so that Faber can offer guidance throughout his daily activities. At Montag's house, Mildred has friends over and Mildred tells them of the foolishness of books. Montag then reads them a poem called Dover Beach and one of Mildred's friends begins to cry. This infuriates another friend and she calls Montag a sick man.

Montag returns to the firehouse the next day with only one of the books, which he tosses into the incinerator. Beatty tells Montag that he had a dream in which they fought endlessly by quoting books to each other. In describing the dream Beatty shows that, despite his disillusionment, he was once an enthusiastic reader. A fire alarm goes off and Beatty picks up the address from the dispatcher system. He reminds Montag of his duty and theatrically leads the crew to the fire engine, which he drives to Montag's house.

Burning Bright

Beatty orders Montag to destroy his own house, telling him that Mildred and the neighbors betrayed him. Montag sees Mildred leaving and sets to work burning their home, including their televisions, beds, and other emblems of his past life. After Montag destroys the house, Beatty discovers Montag's earpiece and plans to hunt down Faber. Montag threatens Beatty with the flamethrower and, after Beatty continues taunting, kills him. As he flees the scene the firehouse's mechanical hound attacks him, numbing one of his legs with a tranquilizer needle. He destroys it with the flamethrower and limps away.

He flees through the city streets, arriving at Faber's house. Faber urges him to make his way to the countryside and contact the exiled book-lovers who live there. On Faber's television they watch news reports of another mechanical hound being released, with news helicopters following it to create a public spectacle. Montag leaves Faber's house and escapes the manhunt by jumping into a river and floating downstream into the countryside. There, he meets a group of older men led by a man named Granger, who, to Montag's astonishment, have memorized entire books, preserving them orally until the law against books is overturned. They burn the books they read to prevent discovery, retaining the verbatim content in their minds. Meanwhile, the television network helicopters record the hound killing another innocent man instead of Montag, to maintain the illusion of a successful hunt for the watching audience.

The war begins. Montag watches helplessly as jet bombers fly overhead and attack the city with nuclear weapons. It is implied Mildred dies, though Faber is stated to have left for St. Louis, to "see a retired printer there". It is implied that more cities across the country have been incinerated as well; a bitter irony in that the world that sought to burn is burned itself.

During breakfast at dawn, Granger discusses the legendary phoenix and its endless cycle of long life, death in flames, and rebirth, adding that the phoenix must have some relation to mankind, which constantly repeats its mistakes. Granger then muses that a large factory of mirrors should be built, so that mankind can take a long look at itself. After the meal is over, the band sets off back toward the city, to help rebuild what is left of it.

Characters

- Guy Montag is the protagonist and fireman who presents the dystopia through the eyes of a loyal worker to it, a man in conflict about it, and one resolved to be free of it. Through most of the book, Montag lacks knowledge and believes what he hears. Bradbury notes in his afterword that he noticed, after the book was published, that Montag is the name of a paper company.

- Clarisse McClellan is a young woman who walks with Montag on his trips home. She is unusual sort of person in the bookless society: outgoing, naturally cheerful, unorthodox, and intuitive. She is unpopular among peers and disliked by teachers for asking "why" instead of "how' and focusing on nature rather than on technology. A few days after their first meeting she disappears without any explanation, although Captain Beatty claims she was killed in a car accident. In the afterword of a later edition, Bradbury notes that the film adaptation changed the ending so that Clarisse was living with the exiles. Bradbury, far from being displeased by this, was so happy with the new ending that he wrote it into his later stage edition.

- Mildred Montag is Guy Montag's wife. She is a drug addict, absorbed in the shallow dramas played on her "parlor walls" (television) and indifferent to the oppressive society around her.

- Captain Beatty is Montag's boss and the fire chief. Once an avid reader, he has come to hate books as a result of life's tragedies and of the fact that books contradict and refute each other. In a scene written years later by Bradbury for the Fahrenheit 451 play, Beatty invites Montag to his house where he shows him walls of books left to molder on their shelves.

- Faber is a former English professor. He has spent years regretting that he did not defend books when he saw the moves to ban them. Montag turns to him for guidance, remembering him from a chance meeting in a park some time earlier. Bradbury notes in his afterword that Faber is part of the name of a German manufacturer of pencils, Faber-Castell.

- Mrs. Bowles and Mrs. Phelps are friends of Mildred. During a social visit to Montag's house, they brag about removing all possible sources of unhappiness in their lives. Yet, as Montag demonstrates with a poetry reading, their happiness is only a facade.

- Granger is the leader of a group of wandering intellectual exiles who memorize books in order to preserve their contents.

Themes

The novel is frequently interpreted as being critical of state-sponsored censorship, but Bradbury has disputed this interpretation. He said in a 2007 interview that the book explored the effects of television and mass media on the reading of literature.[4] Bradbury went even further to elaborate his meaning, saying specifically that the culprit in Fahrenheit 451 is not the state—it is the people.[4] Yet in the paperback edition released in 1979, Bradbury wrote a new coda for the book containing multiple comments on censorship and its relation to the novel. The coda is also present in the 1987 mass market paperback, which is still in print.[5]

In the late 1950s, Bradbury observed that the novel touches on the alienation of people by media:

In writing the short novel Fahrenheit 451 I thought I was describing a world that might evolve in four or five decades. But only a few weeks ago, in Beverly Hills one night, a husband and wife passed me, walking their dog. I stood staring after them, absolutely stunned. The woman held in one hand a small cigarette-package-sized radio, its antenna quivering. From this sprang tiny copper wires which ended in a dainty cone plugged into her right ear. There she was, oblivious to man and dog, listening to far winds and whispers and soap-opera cries, sleep-walking, helped up and down curbs by a husband who might just as well not have been there. This was not fiction.[6]

Reception

Galaxy reviewer Groff Conklin placed the novel "among the great works of the imagination written in English in the last decade or more."[7] Boucher and McComas, however, were less enthusiastic; after noting that Bradbury's imagined future was "not a self-consistent probable world logically developed from specific premises," but a Kafkaesque "irrational nightmare and direct symbol of our own contemporary existence," they faulted the book for being "simply padded, occasionally with startlingly ingenious gimmickry, . . . often with coruscating cascades of verbal brilliance [but] too often merely with words." Concluding that the novel seemed "pretty empty without the creation or development of a recognizable human individual," they acknowledged that many readers "may well disagree violently" with their opinions.[8] Reviewing the book for Astounding Science Fiction, P. Schuyler Miller characterized the title piece as "one of Bradbury's bitter, almost hysterical diatribes," although he praised its "emotional drive and compelling, nagging detail."[9]

Adaptations

Playhouse 90 broadcast "A Sound of Different Drummers" on CBS in 1957. The script, which was written by Robert Alan Aurthur, combined plot ideas from Fahrenheit 451 and Nineteen Eighty-Four; Bradbury sued and eventually won on appeal.[10][11] A film adaptation written and directed by François Truffaut, starring Oskar Werner and Julie Christie was released in 1966.'[12]

BBC Radio produced a one-off dramatisation of the novel in 1982.[13] In 1986, the novel was adapted into a computer text adventure game of the same name.

The Off-Broadway theatre The American Place Theatre presented a one man show adaptation of Fahrenheit 451 as a part of their 2008-2009 Literature to Life season.[14]

In June 2009 a graphic novel edition of the book was published (Published by Hill and Wang). Entitled Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451: The Authorized Adaptation,[15] the paperback graphic adaptation was illustrated by Tim Hamilton. The introduction in the novel is written by Ray Bradbury himself.

The book has also been adapted into a 4 hour 30 minute long audiobook.

References

- ^ Seed, D. (2005). A companion to science fiction. Blackwell companions to literature and culture, 34. Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub. Page 491 - 498

- ^ "About the Book: Fahrenheit 451". The Big Read. National Endowment for the Arts. http://www.ebr.lib.la.us/circ/advisory/onebook/aboutthebookF451.htm.

- ^ Bradbury, Ray About Freedom, raybradbury.com, Date unknown; Boyle Johnston, Amy E. "Ray Bradbury: Fahrenheit 451 Misinterpreted", LA Weekly, May 30, 2007.

- ^ a b Ray Bradbury: Fahrenheit 451 Misinterpreted: "Bradbury still has a lot to say, especially about how people do not understand his most famous literary work, Fahrenheit 451, published in 1953... Bradbury, a man living in the creative and industrial center of reality TV and one-hour dramas, says it is, in fact, a story about how television destroys interest in reading literature."

- ^ "There is more than one way to burn a book. And the world is full of people running about with lit matches. Every minority, be it Baptist / Unitarian, Irish / Italian / Octogenarian / Zen Buddhist / Zionist / Seventh-day Adventist / Women's Lib / Republican / Mattachine / FourSquareGospel feels it has the will, the right, the duty to douse the kerosene, light the fuse….Fire-Captain Beatty, in my novel Fahrenheit 451, described how the books were burned first by the minorities, each ripping a page or a paragraph from this book, then that, until the day came when the books were empty and the minds shut and the library closed forever. Only six weeks ago, I discovered that, over the years, some cubby-hole editors at Ballantine Books, fearful of contaminating the young, had, bit by bit, censored some 75 separate sections from the novel. Students, reading the novel which, after all, deals with the censorship and book-burning in the future, wrote to tell me of this exquisite irony. Judy-Lynn del Rey, one of the new Ballantine editors, is having the entire book reset and republished this summer with all the damns and hells back in place."

- ^ Quoted by Kingsley Amis in New Maps of Hell: A Survey of Science Fiction (1960). Bradbury directly foretells this incident early in the work: "And in her ears the little Seashells, the thimble radios tamped tight, and an electronic ocean of sound, of music and talk and music and talking coming in." p.12

- ^ "Galaxy's 5 Star Shelf", Galaxy Science Fiction, February 1954, p.108

- ^ "Recommended Reading," F&SF, December 1953, p. 105.

- ^ "The Reference Library", Astounding Science Fiction, April 1954, pp.145-46

- ^ William F. Nolan, "Bradbury: Prose Poet in the Age of Space", The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, June, 1963.

- ^ Stephen Bowie. "The Sound of a Single Drummer", The Classic TV History Blog, 19 Aug 2010.

- ^ IMDB

- ^ http://www.suttonelms.org.uk/ray-bradbury.html

- ^ "Literature to Life - Citizenship & Censorship: Raise Your Civic Voice in 2008-09". The American Place Theatre. http://www.americanplacetheatre.org/stage/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=331&Itemid=1. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ^ "Macmillan: Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451: The Authorized Adaptation Ray Bradbury, Tim Hamilton: Books". Us.macmillan.com. http://us.macmillan.com/raybradburysfahrenheit451. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

Further reading

- Tuck, D. H. (1974). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Chicago: Advent. p. 62. ISBN 0-911682-20-1.

- McGiveron, R. O. (Fall 1996). What 'Carried the Trick'? Mass Exploitation and the Decline of Thought in Ray Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451. Extrapolation. 37 (3), 245-256.

- McGiveron, R. O. (Spring 1996). Bradbury's Fahrenheit 451. Explicator. 54 (3), 177. ISSN 00144940

- Smolla, R. A. (April 2009). The Life of the Mind and a Life of Meaning: Reflections on Fahrenheit 451. Michigan Law Review. 107 (6), 895-912.

External links

- Fahrenheit 451 publication history at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Hugo Award for Best Novel (1946–1960) Retro Hugos The Mule by Isaac Asimov (1946) · Farmer in the Sky by Robert A. Heinlein (1951) · Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury (1954)

1953–1960 The Demolished Man by Alfred Bester (1953) · They'd Rather Be Right (aka: The Forever Machine) by Mark Clifton and Frank Riley (1955) · Double Star by Robert A. Heinlein (1956) · The Big Time by Fritz Leiber (1958) · A Case of Conscience by James Blish (1959) · Starship Troopers by Robert A. Heinlein (1960)

Complete list · 1946–1960 · 1961–1980 · 1981–2000 · 2001–present

Categories:- 1953 novels

- American philosophical novels

- Dystopian novels

- Fahrenheit 451

- Novels by Ray Bradbury

- Prometheus Award winners

- Works about censorship

- Works originally published in Galaxy Science Fiction

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.