- Corruption in the People's Republic of China

-

Political corruption

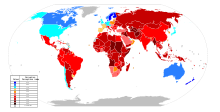

Corruption Perceptions Index, 2010Concepts Electoral fraud · Economics of corruption

Nepotism · Bribery · Cronyism · Slush fundCorruption by country Angola · Armenia · Canada

Chile · China (PRC) · Colombia

Cuba · Ghana · India · Iran · Kenya

Ireland · Nigeria · Pakistan

Paraguay · Philippines · Russia

South Africa · Ukraine · Venezuela

· United StatesThe People's Republic of China suffers from widespread corruption. For 2010, China was ranked 78 of 179 countries in Transparency International's Corruption Perceptions Index, ranking slightly above fellow BRIC nations India and Russia, but below Brazil and most developed countries. Means of corruption include graft, bribery, embezzlement, backdoor deals, nepotism, patronage, and statistical falsification.[1]

Cadre corruption in post-1949 China lies in the "organizational involution" of the ruling party, including the Chinese Communist Party's policies, institutions, norms, and failure to adapt to a changing environment in the post-Mao era[2] caused by the market liberalization reforms initiated by Deng Xiaoping. Like other socialist economies that have gone through monumental transition, such as post-Soviet Eastern Europe and Central Asia, post-Mao China has experienced unprecedented levels of corruption,[3] making corruption one of the major hindrances to the PRC's social and economic development.

Public surveys on the mainland since the late 1980s have shown that it is among the top concerns of the general public. According to Yan Sun, Associate Professor of Political Science at the City University of New York, it was corruption, rather than democracy as such, that lay at the root of the social dissatisfaction that led to the Tiananmen protest movement of 1989.[3] Corruption undermines the legitimacy of the CCP, adds to economic inequality, undermines the environment, and fuels social unrest.[4]

Since then, corruption has not slowed down as a result of greater economic freedom, but instead has grown more entrenched and severe in its character and scope. In popular perception, there are more dishonest CCP officials than honest ones, a reversal of the views held in the first decade of reform of the 1980s.[3] China specialist Minxin Pei argues that failure to contain widespread corruption is among the most serious threats to China's future economic and political stability.[4] Bribery, kickbacks, theft, and misspending of public funds costs at least three percent of GDP.

Contents

Historical overview

Imperial China

The spread of corruption in traditional China is often connected to the Confucian concept of renzhi, "government of the people" as opposed to the legalist "government of the law". Profit (li) was despised as preoccupation of the base people, while the true Confucians were supposed to be guided in their actions by the moral principle of justice (yi). Thus, all relations were based solely on mutual trust and propriety. As a matter of course, this kind of moral uprightness could be developed only among a minority. The famous attempt of Wang Anshi to institutionalize the monetary relations of the state, thus reducing corruption, were met with sharp criticism by the Confucian elite. As a result, corruption continued to be widespread both in the court (Wei Zhongxian, Heshen) and among the local elites, and became one of the targets for criticism in the novel Jin Ping Mei. Another kind of corruption came about in Tang China, developed in connection with the imperial examination system.

Republican era

The widespread corruption of the Kuomintang, the Chinese Nationalist Party, is often credited as being an important component in the defeat of the KMT by the Communist People's Liberation Army. Though the Nationalist Army was initially better equipped and had superior numbers, the KMT's rampant corruption damaged its popularity, limited its support base, and helped the communists in their propaganda war.

See History of the Republic of China, and Black gold (politics) for more on these topics.

In the PRC

Getting high quality, reliable, and standardised survey data on the severity of corruption in the PRC is enormously difficult. However, a variety of sources can still be tapped, which "present a sobering picture," according to Minxin Pei.[5]

Official deviance and corruption have taken place at both the individual and unit level since the founding of the PRC. Initially the practices had much to do with the danwei system, an outgrowth of communist wartime organs.[6] In the PRC the reforms of Deng Xiaoping were much criticized for making corruption the price of economic development. Corruption during Mao's reign also existed, however.[7]

Emergence of the private sector inside the state economy in post-Mao China has tempted CCP members to misuse their power in government posts; the powerful economic levers in the hands of the elite has propelled the sons of some party officials to the most profitable positions. For this, the CCP has been called the "princelings' party" (taizidang), a reference to familiar patterns of corruption in some periods of Imperial China. Attacking corruption in the Party was one of the forces behind the Tiananmen protests of 1989.[8]

In 2010, in a rare move due to its perceived impact on stability, Li Jinhua, vice-chairman of the national committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference and former long-serving auditor general of the National Audit Office, fired a warning shot in the People's Daily, calling for better legal structures and greater supervision over the business dealings of officials and their children. He said the rapidly growing wealth of Communist officials’ children and family members "is what the public is most dissatisfied about".[8]

The politically unchallenged regime in China creates opportunities for cadres to exploit and control the rapid growth of economic opportunities; and while incentives to corruption grow, effective countervailing forces are absent.[9]

Both structural and non-structural corruption has been prevalent in China. Non-structural corruption exists around the world, and refers to all activities that can be clearly defined as "illegal" or "criminal," mainly including different forms of graft: embezzlement, extortion, bribery etc. Structural corruption arises from particular economic and political structures; this form is difficult to root out without a change of the broader system.[6]

Weak state institutions are blamed for worsening corruption in reform-era China. New Left scholars on China criticise the government for apparent "blind faith" in the market, and especially for its erosion of authority and loss of control of local agencies and agents since 1992. Others also see strong links between institutional decline and rising corruption.[10] Corruption in China results from the Party-State's inability to maintain a disciplined and effective administrative corps, according to Lü Xiaobo, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Barnard College. The Chinese reform-era state has also been an enabling factor, since state agencies have been granted regulatory power without institutional constraints, allowing them to tap into new opportunities to seek profits from the rapid growth in businesses and the economy. This takes place at both the departmental and individual level.[11] Corruption here is part of the dilemma faced by any reforming socialist state, where the state needs to play an active role in creating and regulating markets, while at the same time its own intervention places extra burdens on administrative budgets. Instead of being able to reduce the size of its bureaucratic machinery (and therefore opportunities for corruption), it is instead pressed to expand further. Officials then cash in on the regulatory power by "seeking rents."[12]

Public perceptions

Opinion surveys of Party officials and Chinese citizens over recent years set identify corruption as one of the public's top concerns. Every year researchers at the Central Party School, the CCP organ that trains senior and midlevel officials, survey over 100 officials at the school. Between 1999 to 2004 respondents ranked corruption as either the most serious or second most serious social problem.[4] Similarly, in late 2006 the State Council’s Development Research Center asked 4,586 business executives (87 percent in nonstate firms) to rate their local officials in terms of integrity. Almost one-quarter said that their local officials were “bad”; 12 percent said they were “very bad.”[4]

In a commercial environment, corruption may be prevalent because many employees aren't loyal to their employers, seeing themselves as "free-agent entrepreneurs" first and foremost.[13] They use their employers as a way to make money, both for themselves and for their "guanxi social-circle network." The imperative of maintaining this social circle of benefits is seen as a primary goal for many involved in corruption.[13]

Official corruption is among the populace's greatest gripes against the regime. One folk saying vividly illustrates how the public sees the issue, according to Yan Sun: "If the Party executes every official for corruption, it will overdo a little; but if the Party executes every other official for corruption, it cannot go wrong."[3] In contemporary China, bribe taking has become so entrenched that one party secretary in a poor county received repeated death threats for rejecting over 600,000 Renminbi in bribes during his tenure. In 1994 in another area officially designated "impoverished," a delegation of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization arrived for a conference on development, but upon seeing rows of imported luxury cars outside the conference site asked the local officials "Are you really poor?"[3] A rare online opinion poll in 2010 by the People’s Daily found that 91% of respondents believe all rich families in China have political backgrounds.[8]

Means

Broadly defined, three types of corruption are common in China: graft, rent-seeking, and prebendalism.[14]

Graft is the most common and refers to bribery, illicit kickbacks, embezzlement, and theft of public funds. Graft involves something of value given to, and accepted by, public officials for dishonest or illegal purposes. It include officials spending fraudulently or using public funds for their own benefit.[14]

Rent-seeking refers to all forms of corrupt behaviour by people with monopolistic power. Public officials, through granting a license or monopoly to their clients, get "rents"—additional earnings as a result of a restricted market. Rent-seeking happens when officials grant rents to those in their favor.[14] This is akin to cronyism. In the Chinese case, public officials are both rent-generators and rent-seekers, both making rent opportunities for others and seeking such opportunities to benefit themselves. This may include profiteering by officials or official firms, extortion in the form of illicit impositions, fees, and other charges.[14]

Prebendalism refers to when incumbents of public office get privileges and perquisites through that office.[14] Controlling an office entitles the holder to rents or payments for real or fake activities, and organizations are turned from places of work into "resource banks" where individuals and groups pursue their own interests. Prebendal corruption doesn't necessarily need to be about monetary gain, but may include usurpation of official privilege, backdoor deals, clientelism, cronyism, nepotism.[14]

Corruption in the PRC has developed in two major ways. In the first mode, corruption is in the form of ostensibly legal official expenditure, but is actually wasteful and directed toward private benefits. For example, the increasing number of local governments building massive administrative office buildings that resemble luxurious mansions.[5] At the same time, many corrupt local officials have turned their jurisdictions into virtual “mafia states,” where they collude with criminal elements and unsavory businessmen in illegal activities.[5]

While the state and its bureaucrats are major players in the reform-era economy, new interests and concentrations of economic have been created, without legitimate channels between administrators and entrepreneurs.[9] A lack of regulation and supervision has meant these roles are not clearly demarcated (Lü Xiaobo in his text titles one section "From Apparatchiks to Entrepreneurchiks").[15] Illicit guandao enterprises formed by networks of bureaucrats and entrepreneurs are allowed to grow, operating behind a facade of a government agency or state-owned enterprise, in a realm neither fully public nor private.[9]

The PLA has also become a major economic player, and participant in large and small scale corruption at the same time. Inconsistent tax policy, and a politicised and poorly organised banking system, create ample opportunities for favouritism, kickbacks, and "outright theft," according to Michael Johnston, Professor of Political Science at Colgate University in Hamilton, New York.[9]

Corruption has also taken the form of collusion between CCP officials and criminal gangs. Often hidden inside legitimate businesses, gangs had infiltrated public offices and worked closely with the police.[16] The Telegraph quoted an employee of a state company saying: "In fact, the police stations in Chongqing were actually the centre of the prostitution, gambling and drugs rackets. They would detain gangsters from time to time, and sometimes send them to prison, but the gangsters described it as going away for a holiday. The police and the mafia were buddies." In some cases, innocents were hacked to death and dismembered by roaming gangs whose presence was allowed by regime officials, according to the Telegraph.[16]

China's housing boom, and the shift of central government policy towards social housing, are providing officials to siphon off properties for personal gain. The Financial Times cites a number of public scandals involving local officials in 2010: for example, in province, eastern China, a complex of 3,500 apartments designated as social housing in Rizhao, Shandong, was sold to local officials at prices 30-50 per cent below market values. It said in Meixian, Sha’anxi, around 80 per cent of the city’s first social housing development, called Urban Beautiful Scenery, went to local officials. In Xinzhou, Shanxi, a new complex of 1,578 apartments on the local government’s list of designated social housing was almost entirely reserved for local officials, many were 'flipped' for tidy profits even before construction was completed. Jones Lang LaSalle said that transparency about the plans for affordable housing was severely lacking.[17]

Effects

Whether the effects of corruption in China are solely positive or negative is a subject of hot debate. Corruption favors the most connected and unscrupulous, rather than the efficient, and also creates entry barriers in the market for those without such connections. Favors are sought for inefficient subsidies, monopoly benefits, or regulatory oversight, rather than productive activity.[18] Bribes also lead to a misdirection of resources into wasteful or poor-quality projects. Further, since corrupt payments are usually done secrecy, they are more likely to be used in the same way, driving the proceeds of illegal transactions into foreign bank accounts. Such capital flight costs national growth.[18] Centralised corruption also carries with it the same defects, according to Yan. Rent seeking, for example, is costly to growth because it prevents innovation. Rent seeking activities are also self-sustaining, since such activity makes it seem more attractive compared to productive activity. Corruption is never a better option to honest public policy, Yan Sun argues, and it distorts and retards development.[19]

Others, including local officials, play down the negative impacts of corruption, and local cadres frown on anticorruption efforts for three reasons: a preoccupation with rooting out corruption may lead to cautiousness about new practices; corruption may act as a "lubricant" to "loosen up" the bureaucracy and facilitate commercial exchanges; and thirdly, corruption is a necessary trade-off and inevitable part of the process of reform and opening up.[20] They argue that the destructiveness of corruption in the Chinese context helps transfer or reallocate power from officials, perhaps even enabling the rise of a "new system" and acting as a driving force for reform.[21]

Nevertheless, the deleterious effects of corruption were documented in detail in Minxin Pei's report. The amount of money stolen through corruption scandals has risen exponentially since the 1980s, and corruption in China is now more concentrated in the sectors the state is heavily involved with.[4] These include infrastructure projects, real estate, government procurement, and financial services. The lack of a competitive political process means these are high-risk areas for fraud, theft, and bribery; Pei estimates the cost of corruption could be up to $86 billion per year.[4]

Corruption in China also harms Western business interests[22], in particular foreign investors. They risk human rights, environmental, and financial liabilities, at the same time squaring off against rivals who engage in illegal practices to win business.[4]

Long term, corruption has potentially "explosive consequences," including widening income inequalities within cities and between city and countryside, and creating a new, highly-visible class of "socialist millionaires," which further fuels resentment from the citizenry.[9]

Ordinary Chinese are sometimes the victims in official corruption, as in the case of Hewan village in Jiangsu province, where 200 thugs were hired to attack local farmers and force them off their land so Party bosses could build a petrochemical plant. Sun Xiaojun, the party chief of Hewan village, was later arrested. One farmer died.[23] Officials themselves are increasingly victims of official corruption when they target each other out of jealousy, hunger for promotion: there have been high-profile cases of mainland bureaucrats employing hit men or launching acid attacks on rivals. In August 2009, a former director of the Communications Bureau in Hegang, Heilongjiang, who hired hitmen to kill his successor, supposedly because of the latter's ingratitude was given the death penalty.[24]

Countermeasures

The CCP has tried a variety of anti-corruption measures, constructing a variety of laws and agencies in an attempt to stamp out corruption.

In 2004, the CCP devised strict regulations on officials assuming posts in business and enterprise. The Central Committee for Discipline Inspection and the Central Organisation Department issued a joint circular instructing Party committees, governments and related departments at all levels not to give approval for Party and government officials to take up concurrent posts in enterprises.[25]

Such measures are largely ineffective, however, due to the insufficient enforcement of the relevant laws.[5] Further, because the Central Commission of Discipline Inspection largely operates in secrecy, it is unclear to researchers how allegedly corrupt officials are disciplined and punished. The odds for a corrupt official to end up in prison are less than three percent, making corruption a high-return, low risk activity. This leniency of punishment has been one of the main reasons corruption is such a serious problem in China.[5]

While corruption has grown in scope and complexity, anti-corruption policies, on the other hand, have not changed much.[9] Communist-style mass campaigns with anti-corruption slogans, moral exhortations, and prominently-displayed miscreants, are still a key part of official policy, much as they were in the 1950s.[9]

In 2009, according to internal Party reports, there were 106,000 officials found guilty of corruption, an increase of 2.5 percent on the previous year. The number of officials caught embezzling more than one million yuan (US$146,000) went up by 19 percent over the year. With no independent oversight like NGOs or free media, corruption has flourished.[26]

These efforts are punctuated by an occasional harsh prison term for major offenders, or even executions. But rules and values for business and bureaucratic conduct are in flux, sometimes contradictory, and “deeply politicized.”[9] In many countries systematic anti-corruption measures include independent trade and professional associations, which help limit corruption by promulgating codes of ethics and imposing quick penalties, watchdog groups like NGOs, and a free media. In China, these measures do not exist as a result of the CCP’s means of rule.[9]

Thus, while Party disciplinary organs and prosecutorial agencies produce impressive statistics on corruption complaints received from the public, few citizens or observers believe corruption is being systematically addressed.[9]

There are also limits to how far anti-corruption measures will go. For example, when Hu Jintao's son was implicated in a corruption investigation in Namibia, Chinese Internet portals and Party-controlled media were ordered not to report on it.[27]

At the same time, local leaders engage in "corruption protectionism," as coined by the head of the Hunan provincial Party Discipline Inspection Commission; apparatchiks thwart corruption investigations against the staff of their own agencies, allowing them to escape punishment. In some cases this has impelled high-ranking officials to form special investigative groups with approval from the central government to avoid local resistance and enforce cooperation.[28] However, since in China vertical and horizontal leadership structures often run at odds with one another, CCP anti-corruption agencies find it hard to investigate graft at the lower levels. The goal of effectively controlling corruption thus remains elusive to the ruling Party.[28]

Political incentives for cracking down

Prominent anti-corruption cases in China are often an outgrowth of factional struggles for power in the CCP, as opponents use the "war of corruption" as a weapon against rivals in the Party or corporate world.[27] Often, too, the central leadership's goal in cracking down on corruption is to send a message to those who step over some "unknown acceptable level of graft" or too obviously flaunt its benefits. Another reason is to show an angry public that the Party is doing something about the problem.[27]

In many such cases, the origins of anti-corruption measures are a mystery. When Chen Liangyu was ousted, analysts said it was because he lost a power struggle with leaders in Beijing. Chen was Shanghai's party secretary and member of the powerful Politburo.[27] In 2010 a re-release of the Communist Party of China 52 code of ethics was published.

Individuals

- Implicated

Prominent individuals implicated in corruption in China include: Wang Shouxin, Yang Bin, Chen Liangyu, Qiu Xiaohua (the nation's chief statistician, who was sacked and arrested in connection with a pension-fund scandal)[29], Zheng Xiaoyu[29], Lai Changxing[29], Lan Fu, Xiao Zuoxin, Ye Zheyun, Chen Xitong, Tian Fengshan, Zhu Junyi.

- Researchers

Authors who have written about corruption in China include: Liu Binyan, Robert Chua, Wang Yao, Li Zhi, Lü Gengsong, Xi Jinping, Jiang Weiping.

- Whistleblowers

The strict controls placed on the media by the Chinese government limit the discovery and reporting of corruption in China. Nevertheless, there have been cases of whistleblowers publicising corruption in China.

See Media of the People's Republic of China for a discussion on the media in China, including topics such as censorship and controls.

See also

- Anti-corruption organizations

- Anti-Corruption and Governance Research Center, School of Public Policy and Management, Tsinghua University, Beijing

- International Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (IAACA) in Beijing

- Three-anti/five-anti campaigns (1951/1952)

- Central Commission for Discipline Inspection of the Communist Party of China

- Ministry of Supervision of the People's Republic of China

- National Bureau of Corruption Prevention (NBCP) (website) (Chinese Wikipedia)

- Independent Commission Against Corruption (Hong Kong)

- Commission Against Corruption (Macau)

- Cases

- Shanghai pension scandal

- Allegations of corruption in the construction of Chinese schools of the 2008 Sichuan earthquake

- Chongqing gang trials

- P Chips Frauds

- S-Chips Scandals

- China Stock Frauds

- Society

- Guanxi (personal relationships in Chinese culture)

- Capital punishment in the People's Republic of China

- Prostitution in the People's Republic of China

- Law enforcement in the People's Republic of China

- Penal system in the People's Republic of China

- International corruption index

References

Bibliography

- Lü, Xiaobo (2000). Cadres and Corruption. Stanford University Press.

- Yan, Sun (2004). Corruption and Market in Contemporary China. Cornell University Press.

- Manion, Melanie (2004). Corruption by Design. Harvard University Press.

- Hutton, Will (2007). The Writing on the Wall: China and the West in the 21st Century. Little, Brown.

Footnotes

- ^ Lü 2000, p.10

- ^ Lü 2000, p.229

- ^ a b c d e Yan 2004, p. 2

- ^ a b c d e f g Minxin Pei, Corruption Threatens China's Future, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Policy Brief No. 55, October 2007.

- ^ a b c d e Minxin Pei, Daniel Kaufmann, Corruption in China: How Bad is It?, November 20, 2007.

- ^ a b Lü 2000, p. 236

- ^ Lü 2000, p. 235: "It is true that corruption by cadres existed in the Maoist era."

- ^ a b c Anderlini, Jamil (12 March 2010). "Chinese officials’ children in corruption claim", Financial Times

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Michael Johnston, "Corruption in China: Old Ways, New Realities and a Troubled Future", United Nations Public Administration Network, accessed January 29, 2010

- ^ Yan 2004, p.8

- ^ Lü 2000, p. 252

- ^ Lü 2000, p. 254

- ^ a b Shaun Rein, "How to Deal with Corruption in China", Forbes.com, July 10, 2009

- ^ a b c d e f Lü 2000, p.14

- ^ Lv 2000, p. 242

- ^ a b Malcolm Moore, "China corruption trial exposes capital of graft", The Telegraph, October 17, 2009

- ^ Dyer, Geoff (18 June 2010). "Housing boom fuels corruption in China"

- ^ a b Yan 2004, p. 12

- ^ Yan 2004, p. 11

- ^ Yan 2004, p. 18

- ^ Yan 2004, p. 19

- ^ http://www.globaltimes.cn/www/english/metro-beijing/update/top-news/2010-05/530235.html

- ^ AsiaNews/Agencies, "Corruption in China: Communist official and Supreme Court justice imprisoned," AsiaNews.it, January 19, 2010

- ^ Wang Xiangwei (28 Jun 2010). CHINA BRIEFING: "More officials trying to get away with murder", South China Morning Post

- ^ Transparency International, "Chinese National Integrity System Study 2006", December 7, 2006

- ^ Quentin Sommerville, "Corruption up among China government officials", BBC, January 9, 2009

- ^ a b c d David Barboza, "Politics Permeates Anti-Corruption Drive in China", New York Times, September 3, 2009.

- ^ a b Lü 2000, p. 227

- ^ a b c Kent Ewing (1 March 2007). "Resentment builds against China's wealthy", Asia Times.

External links

- Transparency International - international research and policies

- Chinese National Integrity System Study

- Promoting Transparent Procurement and strengthening Corporate Responsibility in China

- Systemic Corruption in the Construction Sector brings Chinese and International Experts Together

- China's Governance Crisis Report

People's Republic of China topics

People's Republic of China topicsHistory China (timeline) · Republic of China (1912–1949) · People's Republic of China · 1949-1976 · 1976-1989 · 1989-2002 · since 2002 · Years in the People's Republic of ChinaGeography · Natural environment Overviews Regions Terrain Bays · Canyons · Caves · Deserts · Grasslands · Hills · Islands · Mountains (ranges · passes) · Peninsulas · Northeast / North / Central Plains · Valleys · VolcanoesWater Seas Reserves Wildlife Fauna · FloraGovernment · Politics · Economy Government

and politicsConstitution · National People's Congress · President · Vice President

State Council (Premier · Vice Premier) · Civil service · Military (People's Liberation Army) · Political parties (Communist Party) · Elections · Education (universities) · National security · Foreign relations · Public health · Food safety (incidents) · Social welfare · Water supply and sanitationAdministrative

divisionsProvince level subdivisions · Cities · Baseline islands ·

Border crossingsLaw Economy History · Historical GDP · Reform · Finance · Banking (Central bank) · Currency · Agriculture · Energy · Technological and industrial history · Science and technology · Transport · Ports and harbors · Communications · Special Economic Zones (SEZs) · Foreign aid · Standard of living · PovertyPeople · Culture People Society Corruption · Crime · Urban life · Rural life · Harmonious society · Xiaokang · Women · Sexuality · Social issues · Social relations · Social structure · Generation Y · IntellectualismCulture Art · Cinema · Cuisine · Literature · Media · Newspapers · Music · Philosophy · Tourism · Sports · Martial arts · Variety arts · Tea culture · Smoking · Television · Public holidays · World Heritage Sites · Archaeology · Parks · Gardens · Libraries · ArchivesOther topics  Category ·

Category ·  Portal ·

Portal ·  WikiProject

WikiProjectCorruption in Asia Sovereign

states- Afghanistan

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Bahrain

- Bangladesh

- Bhutan

- Brunei

- Burma (Myanmar)

- Cambodia

- People's Republic of China

- Cyprus

- East Timor (Timor-Leste)

- Egypt

- Georgia

- India

- Indonesia

- Iran

- Iraq

- Israel

- Japan

- Jordan

- Kazakhstan

- North Korea

- South Korea

- Kuwait

- Kyrgyzstan

- Laos

- Lebanon

- Malaysia

- Maldives

- Mongolia

- Nepal

- Oman

- Pakistan

- Philippines

- Qatar

- Russia

- Saudi Arabia

- Singapore

- Sri Lanka

- Syria

- Tajikistan

- Thailand

- Turkey

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

- Uzbekistan

- Vietnam

- Yemen

States with limited

recognition- Abkhazia

- Nagorno-Karabakh

- Northern Cyprus

- Palestine

- Republic of China (Taiwan)

- South Ossetia

Dependencies and

other territories- Christmas Island

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Hong Kong

- Macau

Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.