- Omagh bombing

-

Coordinates: 54°36′0″N 7°17′52″W / 54.6°N 7.29778°W

Omagh bombing Part of The Troubles

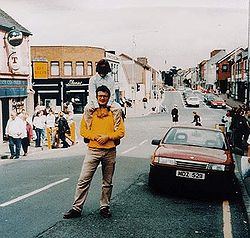

The red Vauxhall Cavalier containing the bomb. This photograph was taken shortly before the explosion; the camera was found afterwards in the rubble. The Spanish man and child seen in the photo both survived.[1]Location Omagh, Northern Ireland Date 15 August 1998

3.10 p.m. (BST)Target Courthouse[2] Attack type Car bomb Death(s) 29[3][4][5][6] Injured About 220 initially reported,[7] later stories say over 300.[4][8][9] Perpetrator(s) Real IRA (RIRA)[4][5][6] The Omagh bombing was a car bomb attack carried out by the Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA), a splinter group of former Provisional Irish Republican Army members opposed to the Good Friday Agreement, on Saturday 15 August 1998, in Omagh, County Tyrone, Northern Ireland.[7] Twenty-nine people died as a result of the attack and approximately 220 people were injured.[3][4][5][6][10] The attack was described by the BBC as "Northern Ireland's worst single terrorist atrocity" and by the British Prime Minister, Tony Blair, as an "appalling act of savagery and evil".[9] Sinn Féin leaders Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness condemned the attack and the RIRA itself.[11]

The victims included people from many different backgrounds: Protestants,[12] Catholics,[12] a Mormon teenager,[12] five other teenagers,[12] six children,[12][13] a woman pregnant with twins,[12][13] two Spanish tourists,[12] and other tourists on a day trip from the Republic of Ireland.[8] The nature of the bombing created a strong international and local outcry against the RIRA, which later apologised,[14] and spurred on the Northern Ireland peace process.[3][4][14][15]

A retrospective report by the Police Ombudsman, Nuala O'Loan, in December 2001 concluded that people "were let down by defective leadership, poor judgement and a lack of urgency" in the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).[16] The RUC has obtained circumstantial and coincidental evidence against some suspects, but it has not come up with anything to convict anyone of the bombing.[17] Builder and publican Colm Murphy was tried, convicted, and then released after it was revealed that the Gardaí forged interview notes used in the case.[18] Murphy's nephew Sean Hoey was also tried and found not guilty. Police Service of Northern Ireland Chief Constable Sir Hugh Orde said that he expects no further prosecutions.[19] In June 2009, the families of all the killed victims won a £1.6 million civil action against four unconvicted suspects.[20]

Contents

Background

Negotiations to end the Troubles had failed in 1996 and there was a resumption of political violence. The peace process later resumed, and it reached a point of renewed tension in 1998, especially following the deaths of three Catholic children in Orange Order-related riots in mid-July.[21] Sinn Féin had accepted the Mitchell Principles, which involved commitment to non-violence, in September 1997 as part of the peace process negotiations.[22] Dissident members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA), who saw this as a betrayal of the republican struggle for a united Ireland, left to form the Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA) in October 1997.[22][23]

The RIRA began its paramilitary campaign against the Agreement with an attempted car bombing in Banbridge, County Down on 7 January 1998, which involved a 300 lb explosive that was defused by security forces.[23] Later that year, it mounted attacks in Moira, Portadown, Belleek, Newtownhamilton and Newry, as well as bombing Banbridge again on 1 August, which caused thirty-five injuries and no deaths.[23] The attack at Omagh took place thirteen weeks after the signing of the Good Friday Agreement, which had been intended to be a comprehensive solution to the Troubles and had broad support both in Ireland and internationally.[24][25]

The attack

Preparation and warnings

On 13 August, a maroon Vauxhall Cavalier was stolen from Carrickmacross, County Monaghan, in the Republic of Ireland.[26] The perpetrators replaced its Republic of Ireland number plates with false Northern Ireland plates.[13][26] On the day of the bombing, they drove the car across the Irish border and at about 14:19 parked the vehicle filled with 230 kg [500 pounds] of fertiliser-based explosives outside S.D. Kells' clothes shop in Omagh's Lower Market Street, on the southern side near its intersection with Dublin Road.[13] They could not find a parking space near the intended target, the Omagh courthouse.[27] The car (with its false registration number MDZ 5211) had arrived from an easterly direction. The two male occupants then armed the bomb and upon exiting the car, walked east down Market Street towards Campsie Road.

Three phone calls were made warning of a bomb in Omagh, using the same codeword that had been used in the Real IRA's bomb attack in Banbridge two weeks earlier.[28][29] At 14:32, a warning was telephoned to Ulster Television saying, "There's a bomb, courthouse, Omagh, main street, 500lb, explosion 30 minutes."[28] One minute later, the office received a second warning saying, "Martha Pope (which was the RIRA's code word), bomb, Omagh town, 15 minutes".[28] The next minute, the Coleraine office of the Samaritans received a call stating that a bomb would go off on "main street" about 200 yards (180 m) from the courthouse.[28] The recipients passed on the information to the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).[28]

The BBC News stated that police "were clearing an area near the local courthouse, 40 minutes after receiving a telephone warning, when the bomb detonated. But the warning was unclear and the wrong area was evacuated".[10] The warnings mentioned "main street" when no street by that name existed in Omagh, although Market Street was the main shopping street in the town.[26] The nature of the warnings led the police to cordon off High Street and to move people down the hill from the top of that street and the area around the courthouse to the bottom of Market Street where the bomb was actually placed.[4][10][26][28][30] The courthouse is roughly 400 metres from the spot where the car bomb was parked.[30][31]

Explosion

The car bomb detonated at about 15:10 BST in the crowded shopping area,[10] killing outright 21 people who had been in the vicinity of the vehicle. Eight more people would die on the way to or in hospital. The car burst into flames and was blown apart, with molten shrapnel, shards of glass, and car parts flying in all directions for 300 yards. The powerful blast wave which followed tore limbs and clothing off people, and even decapitated one woman as it travelled in a direct line, rebounding off the buildings. The explosion left a crater 80 centimetres deep and three metres wide where several bodies were later found; it had rapidly filled with water from a broken main. Shops on both sides of the narrow street were devastated with fallen masonry and debris covering many of the dead and injured. The deceased victims included a pregnant woman, six children, and six teenagers, most of whom had died on the spot.[32]

Injured survivor Marion Radford described hearing an "unearthly bang", followed by "an eeriness, a darkness that had just come over the place", then the screams as she saw "bits of bodies, limbs or something" on the ground while she searched for her 16 year-old son, Alan. She later discovered he had been killed only yards away from her, the two having become separated minutes before the blast.[33][34]

In a statement on the same day as the bombing, RUC Chief Constable Ronnie Flanagan accused the RIRA of deliberately trying to direct civilians to the bombing site.[31] British government prosecutor Gordon Kerr QC called the warnings "not only wrong but... meaningless" and stated that the nature of the warnings made it inevitable that the evacuations would lead to the bomb site.[35] The RIRA strongly denied that it intended to target civilians.[28][36] It also stated that the warnings were not intended to lead people to the bombing site.[28] During the 2003 Special Criminal Court trial of RIRA director Michael McKevitt, witnesses for the prosecution stated that the inaccurate warnings were accidental.[27]

Aftermath

The BBC News stated that those "who survived the car bomb blast in a busy shopping area of the town described scenes of utter carnage with the dead and dying strewn across the street and other victims screaming for help".[10] The injured were initially taken to two local hospitals, the Tyrone County Hospital and the Erne Hospital.[30] A local leisure centre was set up as a casualty field centre, and Lisanelly Barracks, an army base served as an impromptu morgue.[30][31] The Conflict Archive on the Internet project has stated that rescue workers described the scene as "battlefield conditions".[30] Tyrone County Hospital became overwhelmed, and appealed for local doctors to come in to help.[10][31]

Because of the stretched emergency services, people used buses, cars and helicopters to take the victims to other hospitals in Northern Ireland,[10][31] including the Royal Victoria Hospital in Belfast and Altnagelvin Hospital in Derry.[30] A Tyrone County Hospital spokesman stated that they treated 108 casualties, 44 of whom had to be transferred to other hospitals.[31] Paul McCormick of the Northern Ireland Ambulance Service said that, "The injuries are horrific, from amputees, to severe head injuries to serious burns, and among them are women and children."[10]

The day after the bombing, the relatives and friends of the dead and injured used Omagh Leisure Centre to post news.[30] The Spanish Ambassador to the Republic of Ireland personally visited some of the injured[30] and churches across Northern Ireland called for a national day of mourning.[37] Church of Ireland Archbishop of Armagh Robin Eames stated on BBC Radio that, "From the Church's point of view, all I am concerned about are not political arguments, not political niceties. I am concerned about the torment of ordinary people who don't deserve this."[37]

Reactions

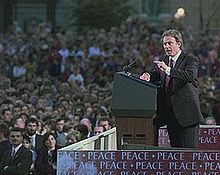

British Prime Minister Tony Blair visited Omagh days after the bombing. This photograph shows Blair addressing a crowd in Armagh several weeks later.

British Prime Minister Tony Blair visited Omagh days after the bombing. This photograph shows Blair addressing a crowd in Armagh several weeks later.

The nature of the bombing created a strong international and local outcry against the RIRA and in favour of the Northern Ireland peace process.[3][4][15] British Prime Minister Tony Blair called the bombing an "appalling act of savagery and evil."[9][10] Queen Elizabeth II expressed her sympathies to the victim's families, while HRH The Prince of Wales paid a visit to the town and spoke with the families of some of the victims.[10][38] The Pope and US President Bill Clinton, who shortly afterwards visited Omagh with his wife Hillary, also expressed their sympathies.[30] Social Democratic and Labour Party President John Hume called the perpetrators of the bombing "undiluted fascists".[15]

Sinn Féin leader Martin McGuinness said that, "This appalling act was carried out by those opposed to the peace process".[10] Party president Gerry Adams said that, "I am totally horrified by this action. I condemn it without any equivocation whatsoever."[11] McGuinness mentioned the fact that both Catholics and Protestants alike were injured and killed, saying, "All of them were suffering together. I think all them were asking the question 'Why?', because so many of them had great expectations, great hopes for the future."[11] Sinn Féin as an organization initially refused to co-operate with the investigation into the attack, citing the involvement of the Royal Ulster Constabulary.[39] On 17 May 2007, Martin McGuinness stated that Irish republicans would co-operate with an independent, international investigation if one is created.[40]

On 22 August 1998, the Irish National Liberation Army called a ceasefire in its operations against the British government.[30][41][42] The National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism[43] has accused the republican paramilitary organization of providing supplies for the bombing.[42] The INLA continued to observe the ceasefire although it remains opposed to the Good Friday Agreement. It recently began decommissioning its arms.[42] The RIRA also suspended operations for a short time after the Omagh bombing before returning to violence.[30] The RIRA came pressure from the Provisional Irish Republican Army after the bombing; PIRA members visited the homes of 60 people connected with the RIRA and ordered them to disband and stop interfering with PIRA arms dumps.[23] The BBC News stated that, "Like the other bombings in the early part of 1998 in places like Lisburn and Banbridge, Omagh was a conscious attempt by republicans who disagreed with the political strategy of Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, to destabilise Northern Ireland in that vulnerable moment of hope. It failed - but there is a terrible irony to the way in which the campaign was halted only by the wave of revulsion triggered by the carnage at Omagh."[3]

Responsibility

Allegations

No group claimed responsibility on the day of the attack, but the RUC suspected the RIRA.[10][31] The RIRA had carried out a car bombing in Banbridge, County Down, two weeks before the Omagh bombing.[31] Three days after the attack, the RIRA claimed responsibility and apologised for the attack.[14][36] On 7 February 2008, a RIRA spokesman stated that, "The IRA had minimal involvement in Omagh. Our code word was used; nothing more. To have stated this at the time would have been lost in an understandable wave of emotion" and "Omagh was an absolute tragedy. Any loss of civilian life is regrettable."[44]

On 9 October 2000, the BBC's Panorama programme aired the special Who Bombed Omagh? hosted by journalist John Ware.[26] The programme quoted RUC Chief Constable Ronnie Flanagan as saying, "sadly up to this point we haven't been able to charge anyone with this terrible atrocity".[26] The programme alleged that the police on both sides of the Irish border knew the identity of the bombers.[26] It stated that, "As the bomb car and the scout car headed for the border, the police believe they communicated by mobile phone. This is based on an analysis of calls made in the hours before, during and after the bombing. This analysis may prove to be the key to the Omagh bomb investigation."[26] Using the phone records, the programme gave the names of the four prime suspects as Oliver Traynor, Liam Campbell, Colm Murphy, and Seamus Daly.[26] The police had leaked the information to the BBC since it was too circumstantial and coincidental to be used in court.[17]

Northern Ireland Secretary Peter Mandelson praised the Panorama programme, calling it "a very powerful and very professional piece of work".[45] Irish Taoiseach Bertie Ahern criticised it, saying that "bandying around names on television" could hinder attempts to secure convictions.[45] First Minister David Trimble stated that he had "very grave doubts" about it.[45] Lawrence Rush, whose wife Elizabeth died in the bombing, tried legally to block the programme from being broadcast, saying, "This is media justice, we can't allow this to happen".[46] Democratic Unionist Party assembly member Oliver Gibson, whose niece Esther died in the bombing, stated that the government did not have the will to pursue those responsible and welcomed the programme.[46]

The police believe that the bombing of BBC Television Centre in London on 4 March 2001 was a revenge attack for the broadcast.[47] On 9 April 2003, the five RIRA members behind the BBC office's bombing were convicted and sentenced for between 16 and 22 years.[48]

Prosecutions and court cases

On 22 September 1998, the RUC and Gardaí arrested twelve men in connection with the bombing.[40] They subsequently released all of them without charge.[40] On 25 February 1999, they questioned and arrested at least seven suspects.[40] Builder and publican Colm Murphy, from Ravensdale, County Louth, was charged three days later for conspiracy and was convicted on 23 January 2002 by the Republic's Special Criminal Court.[40] He is, as of January 2008, the only person ever convicted in connection with the explosion.[40] He was sentenced to fourteen years.[18] In January 2005, Murphy's conviction was quashed and a retrial ordered by the Court of Criminal Appeal, on the grounds that two Gardaí had falsified interview notes, and that Murphy's previous convictions were improperly taken into account by the trial judges.[18]

On 28 October 2000, the families of four children killed in the bombing — James Barker, 12, Samantha McFarland, 17, Lorraine Wilson, 15, and 20-month-old Breda Devine — launched a civil action against the suspects named by the Panorama programme.[40] On 15 March 2001, the families of all twenty-nine people killed in the bombing launched a £2-million civil action against RIRA suspects Seamus McKenna, Michael McKevitt, Liam Campbell, Colm Murphy, and Seamus Daly.[40] Former Northern Ireland secretaries Peter Mandelson, Tom King, Peter Brooke, Lord Hurd, Lord Prior, and Lord Merlyn-Rees signed up in support of the plaintiffs' legal fund.[40] The civil action began in Northern Ireland on 7 April 2008.[49]

On 6 September 2006, Murphy's nephew Sean Hoey, an electrician from Jonesborough, County Armagh, went on trial accused of 29 counts of murder, and terrorism and explosives charges.[50] Upon its completion, Hoey's trial found on 20 December 2007 that he was not guilty of all 56 charges against him.[51]

On 24 January 2008, former Chief Constable Ronnie Flanagan apologised to the victims' families for the lack of convictions in relation to the Omagh bombing.[52] This apology was rejected by some of the victims' families.[52] After the Hoey verdict, BBC News reporter Kevin Connolly stated that, "The Omagh families were dignified in defeat, as they have been dignified at every stage of their fight for justice. Their campaigning will go on, but the prospect is surely receding now that anyone will ever be convicted of murdering their husbands and brothers and sisters and wives and children."[3] Police Service of Northern Ireland Chief Constable Sir Hugh Orde stated that he believed there would be no further prosecutions.[19]

On 8 June 2009, the civil case taken by victims' relatives concluded, with Michael McKevitt, Liam Campbell, Colm Murphy and Seamus Daly being found to have been responsible for the bombing.[20] Seamus McKenna was cleared of involvement.[20] They were held liable for £1.6 million of damages. It was described as a "landmark" damages award internationally.[53]

Controversy

Police Ombudsman report

Police Ombudsman Nuala O'Loan published a report on 12 December 2001 that strongly criticised the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) over its handling of the bombing investigation.[16][54][55] Her report stated that RUC officers had ignored the previous warnings about a bomb and had failed to act on crucial intelligence.[31][54][55] She went on to say that officers had been uncooperative and defensive during her inquiry.[55] RUC officers said that they had moved people towards the bombing site because the warnings had mentioned the courthouse.[31][55] The report concluded that, "The victims, their families, the people of Omagh and officers of the RUC were let down by defective leadership, poor judgement and a lack of urgency."[16] It recommended the setting up of a new investigation team independent of the new Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI), which had since replaced the RUC, led by a senior officer from an outside police force.[16]

Initially, the Police Association, which represents both senior officers and rank and file members of the Northern Ireland police, went to court to try to block the release of the O'Loan report.[31][55] The Association stated that, "The ombudsman's report and associated decisions constitute a misuse of her statutory powers, responsibilities and functions."[55] The group later dropped its efforts.[31][56] RUC Chief Constable Ronnie Flanagan called the report "grossly unfair" and "an erroneous conclusion reached in advance and then a desperate attempt to find anything that might happen to fit in with that."[16] Other senior police officers also disputed the report's findings.[54][55] Flanagan issued a 190 page counter-report in response,[31] and has also stated that he has considered taking legal action.[16] He argued that the multiple warnings were given by the RIRA to cause confusion and lead to a greater loss of life.[31][57] Assistant Chief Constables Alan McQuillan and Sam Kincaid sent affidavits giving information that supported the report.[55][vague]

The families of the victims expressed varying reactions to the report.[58] Kevin Skelton, whose wife died in the attack, said that, "After the bomb at Omagh, we were told by Tony Blair and the Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, that no stone would be left unturned ... It seems to me that a lot of stones have been left unturned," but then expressed doubt that the bombing could have been prevented.[58] Lawrence Rush, whose wife also died in the attack, said that, "There's no reason why Omagh should have happened - the police have been in dereliction of their duty."[58] Other Omagh residents said that the police did all that they could.[58] The Belfast Telegraph called the report a "watershed in police accountability" and stated that it "broke the taboo around official criticism of police in Northern Ireland".[54] Upon leaving office on 5 November 2007, Nuala O'Loan stated that the report was not a personal battle between herself and Sir Ronnie and did not lead to one.[54] She also stated that the "recommendations which we made were complied with".[54]

Advance warning allegations

On 29 July 2001, a double agent using the pseudonym Kevin Fulton publicly stated that, three days before the Omagh bombing, he told his MI5 handlers that the RIRA was preparing a bomb attack and then gave the bomb-maker's name and location.[31] He stated that MI5 did not pass his information over to the police.[59][60] Sir Ronnie Flanagan called the allegations "an outrageous untruth".[31] In September 2001, British security forces informer Willie Carlin stated that Nuala O'Loan's associates had obtained evidence confirming Fulton's allegations.[59] A spokesman for the Ombudsman neither confirmed nor denied Carlin's assertion when asked.[59]

On 19 October 2003, a transcript was released of a conversation between an informer who stole cars on behalf of the RIRA, Paddy Dixon, and his police handler, John White, recorded shortly before Dixon fled the Republic of Ireland on 10 January 2002. Dixon said in the transcript that "Omagh is going to blow up in their faces".[61] On 21 February 2004, PSNI Chief Constable Hugh Orde called for the Republic of Ireland to hand over Dixon.[31] In March 2006, Chief Constable Orde stated that "security services did not withhold intelligence that was relevant or would have progressed the Omagh inquiry".[62] He also stated that the dissident republican militants investigated by MI5 were members of a different cell than the perpetrators of the Omagh bombing.[62]

GCHQ monitoring

An investigation by the BBC's Panorama programme alleged that GCHQ monitored the mobile phone calls of the bombers on the day of the bombing. Later, the transcripts were sent to Special Branch RUC.[10]

Independent bombing investigation

On 7 February 2008, the Northern Ireland Policing Board decided to appoint a panel of independent experts to review the police's investigation of the bombing. Some of the relatives of the bombing victims criticised the decision, saying that an international public inquiry covering both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland should be established instead. The review is to determine whether enough evidence exists for further prosecutions. It is also to investigate the possible perjury of two police witnesses made during Sean Hoey's trial.[63] Sinn Féin Policing Board member Alex Maskey stated that, "Sinn Féin fully supports the families' right to call for a full cross-border independent inquiry while the Policing Board has its clear and legal obligation to scrutinise the police handling of the investigations." He also stated that, "We recognise that the board has a major responsibility in carrying out our duty in holding the PSNI to account in the interests of justice for the Omagh families".[64]

Victims' support group

The families of the victims of the bomb created the Omagh Support and Self Help Group after the bombing.[65] The organisation is led by Michael Gallagher, who lost his 21-year-old son Aidan in the attack.[66] Its web site provides over 5000 newspaper articles, video recordings, audio recordings, and other information sources relating to the events leading up to and following the bombing as well as information about other terrorist attacks.[67] The group's five core objectives are "relief of poverty, sickness, disability of victims", "advancement of education and protection", "raising awareness of needs and experiences of victims, and the effects of terrorism", "welfare rights advice and information", and "improving conditions of life for victims".[65] The group also provides support to victims of other bombings in Ireland, as well other terrorist bombings, such as the 2004 Madrid train bombings.[65] The group has protested outside meetings of the 32 County Sovereignty Movement, an Irish republican political activist group opposed to the Good Friday Agreement that the families believe is part of the RIRA.[68]

In April 2000, the group argued that the attack breached Article 57 of the Geneva Convention and stated that they will pursue the alleged bombers using international law.[69] Michael Gallagher told BBC Radio Ulster that, "The republican movement refused to co-operate and those people hold the key to solving this mystery. Because they have difficulty in working with the RUC and Gardaí, we can't get justice."[69] In January 2002, Gallagher told BBC News that, "There is such a deeply-held sense of frustration and depression" and called the anti-terrorist legislation passed in the wake of the Omagh bombing "ineffective"."[70] He expressed support for the controversial Panorama programme, stating that it reminded "people that what happened in Omagh is still capable of happening in other towns".[46] In February 2002, Prime Minister Tony Blair declined a written request by the group to meet with him at Downing Street.[71] Group members accused the Prime Minister of ignoring concerns about the police's handling of the bombing investigation.[71] A Downing Street spokesman stated that, "The Prime Minister of course understands the relatives' concerns, but [he] believes that a meeting with the Minister of State at the Northern Ireland Office is the right place to air their concerns at this stage."[71]

The death of Michael Gallagher's son along with his and other families' experiences in the Omagh Support and Self Help Group formed the story of the Channel 4 television film Omagh.[66] Film-maker Paul Greengrass stated that "the families of the Omagh Support and Self Help Group have been in the public eye throughout the last five years, pursuing a legal campaign, shortly to come before the courts, with far reaching implications for all of us and it feels the right moment for them to be heard, to bring their story to a wider audience so we can all understand the journey they have made."[66] In promotion for the film, Channel 4 stated that the group had pursued "a patient, determined, indomitable campaign to bring those responsible for the bomb to justice, and to hold to account politicians and police on both sides of the border who promised so much in the immediate aftermath of the atrocity but who in the families' eyes have delivered all too little."[66]

Memorials

Media memorials

The bombing inspired the song "Paper Sun" by British hard rock band Def Leppard, as noted in the commentary of their album Rock of Ages: The Definitive Collection.[72] The band members wrote the song while they were developing their album Euphoria.[72] Guitarist Vivian Campbell stated that "this had happened as Ireland was just getting used to the idea of peace".[72] Vocalist Joe Elliott has said that, "We had the telly on with the sound off and basically wrote our own soundtrack."[72]

Another song inspired by the bombings was "Peace on Earth" by rock group U2.[73] It includes the line, "They're reading names out over the radio. All the folks the rest of us won't get to know. Sean and Julia, Gareth, Ann, and Breda."[73] The five names mentioned are five of the victims from this attack.[73] Another line, "She never got to say goodbye, To see the colour in his eyes, now he's in the dirt," was about how James Barker, a victim, was remembered by his mother Donna Maria Barker in an article in the Irish Times after the bombing in Omagh.[73] The Edge has described the song as "the most bitter song U2 has ever written".[74] The names of all 29 people killed during the bombing were recited at the conclusion of the group's anti-violence anthem "Sunday Bloody Sunday" during the Elevation Tour.[75]

Omagh memorial

In late 1999, Omagh District Council established the Omagh Memorial Working Group to devise a permanent memorial to the bombing victims.[8] Its members come from both public and private sectors alongside representatives from the Omagh Churches Forum and members of the victims' families.[8] The chief executive of the Omagh Council, John McKinney, stated in March 2000 that, "we are working towards a memorial. It is a very sensitive issue."[76] In April 2007, the Council announced the launch of a public art design competition by the Omagh Memorial Working Group.[8] The group's goal was to create a permanent memorial in time for the tenth anniversary of the bombing on 15 August 2008.[8][77] It has a total budget of £240,000.[8]

Since space for a monument on Market Street itself is limited, the final memorial was to be split between the actual bombing site and the temporary Memorial Garden about 300 metres away.[78] Artist Sean Hillen and architect Desmond Fitzgerald won the contest with a design that, in the words of the Irish Times, "centres on that most primal yet mobile of elements: light."[78] A heliostatic mirror was to be placed in the memorial park tracking the sun in order to project a constant beam of sunlight onto 31 small mirrors, each etched with the name of a victim.[77][78] All the mirrors were then to bounce the light on to a heart-shaped crystal within an obelisk pillar that stands at the bomb site.[77][78]

In September 2007, the Omagh Council's proposed wording on a memorial plaque — "dissident republican car bomb" — brought it into conflict with several of the victims' families.[77] Michael Gallagher has stated that "there can be no ambiguity over what happened on 15 August 1998, and no dancing around words can distract from the truth."[77] The Council appointed an independent mediator in an attempt to reach an agreement with those families.[77] Construction started on the memorial on 27 July 2008.[79]

On 15 August 2008, a memorial service was held in Omagh.[80] Senior government representatives from the UK, the Republic of Ireland and the Stormont Assembly were present, along with relatives of many of the victims.[80] A number of bereaved families, however, boycotted the service and held their own service the following Sunday.[80] They argued that the Sinn Féin-dominated Omagh council would not acknowledge that republicans were responsible for the bombing.[80]

See also

- Timeline of Real IRA actions

- Timeline of the Northern Ireland Troubles

- The Troubles in Omagh

References

- ^ Omagh Bomb: Before the Bomb. By Wesley Johnson. The Ireland Story. Accessed 1 August 2008.

- ^ John Mooney and Michael O'Toole (2004). Black Operations: The Secret War Against the Real IRA. Maverick House. pp. 211–2. ISBN 0-9542945-9-9.

- ^ a b c d e f "How the Omagh case unravelled". BBC News. Published 20 December 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Man cleared over Omagh bombing". CNN.com. Published 20 December 2007. Accessed 9 January 2008.

- ^ a b c "Man cleared of Omagh bombing". The Independent. Published 20 December 2007. Accessed 9 January 2008.

- ^ a b c "Nine years on, the only Omagh bombing suspect is free" The Times. Published 21 December 2007. Accessed 9 January 2008.

- ^ a b "Bomb Atrocity Rocks Northern Ireland". BBC News. 1998-08-16. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/northern_ireland/151985.stm. Retrieved 2007-09-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g Design Competition Launched for Omagh Bomb Memorial. Omagh District Council. Published 17 April 2007. Accessed 18 February 2009.

- ^ a b c "Bravery awards for bomb helpers". BBC News. 1999-11-17. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/524462.stm. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Omagh bombing kills 28". BBC News. 1998-08-16. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/events/northern_ireland/latest_news/152156.stm. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ a b c "Sinn Fein condemnation 'unequivocal'". BBC. Published 16 August 1998. Accessed 9 January 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Those who died in the Omagh bomb, 15 August 1998". By Wesley Johnston. The Ireland Story. Accessed 1 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Omagh: Northern Ireland's Blackest Day". Sky News. Published 20 December 2007.

- ^ a b c Real IRA apologises for Omagh bomb. BBC News. Published 18 August 1998.

- ^ a b c A BLAST OF EVIL. The NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. Initially broadcast 19 August 1998.

- ^ a b c d e f "Omagh bomb report 'grossly unfair'". BBC News. Published 12 December 2001.

- ^ a b Investigative Journalism: Context and Practice. Routledge. 2008. p. 115. ISBN 9780415441445.

- ^ a b c "Relatives disappointed with Omagh ruling". RTÉ News. 2005-01-21. http://www.rte.ie/news/2005/0121/omagh.html. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ a b "The quest to catch Omagh bombers". Irish Times. 15 August 2008. http://www.irishtimes.com/newspaper/breaking/2008/0815/breaking272.htm. Retrieved 13 May 2009.

- ^ a b c "Four found liable for Omagh bomb". RTÉ News. 2009-06-08. http://www.rte.ie/news/2009/0608/omagh.html. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ^ Darby, John (2001). The effects of violence on peace processes. United States Institute of Peace Press. p. 96.

- ^ a b Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA) Federation of American Scientists Accessed 13 May 2009

- ^ a b c d Birth and rise of the IRA – the Real IRA. (Subscription Required) By Seamus McKinney. The Irish News. Published 20 December 2007.

- ^ Deadly Omagh bombing remembered 10 years on CNN, Published 15 August 2008

- ^ Statement to Seanad Éireann on the Omagh Bombing Department of the Taoiseach Accessed 18 February 2009

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Who Bombed Omagh?". BBC. Initially broadcast 9 October 2000.

- ^ a b John Mooney & Michael O'Toole (2004). Black Operations: The Secret War Against the Real IRA. Maverick House. p. 33. ISBN 0-9542945-9-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Omagh bomb warnings released. BBC. Published 18 August 1998.

- ^ How the Real IRA brought murderous mayhem to Omagh on a summer day

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Main Events surrounding the bomb in Omagh". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Accessed 18 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Ulster carnage as bomb blast targets shoppers". The Guardian. Published 16 August 1998.

- ^ "Those who died in the Omagh bomb, 15 August 1998 by Wesley Johnston. Retrieved 29-12-10

- ^ "Who bombed Omagh?", Panorama programme

- ^ "They took away a lot of good lives that day". Belfast Telegraph. Sunday Life. 10 August 2008. Retrieved 29-12-10

- ^ "Trial of man suspected of Omagh bombing begins". The Independent. Published 26 September 2006.

- ^ a b "First Statement issued by the "real" IRA, 18 August 1998". Conflict Archive on the Internet. Accessed 18 February 2009.

- ^ a b "National day of mourning call". BBC News. Published 16 August 1998.

- ^ Sad memories for Prince in Omagh. BBC News. Published 18 August 1998.

- ^ "Omagh families seek online justice". BBC News. Published 17 April 2000.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Timeline: the Omagh bombing". The Guardian. Published 20 December 2007.

- ^ "Terror group says Ulster war is over". The Guardian. Published 9 August 1999.

- ^ a b c "Irish National Liberation Army (INLA)". National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism. Accessed 3 March 2009.

- ^ The National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism

- ^ "Mackey slams Provos as RIRA vows resumption of violence". The Ulster Herald. Published 7 February 2008.

- ^ a b c "Named Omagh 'suspect' in court". BBC. Published 10 October 2000.

- ^ a b c "Omagh programme was 'media justice'". BBC. Published 10 October 2000.

- ^ "Ealing Bomb: The Real IRA". The Independent. Published 4 August 2001.

- ^ "Real IRA bombers jailed". BBC. Published 9 April 2003.

- ^ "Omagh civil case 'unprecedented' ". BBC News. Published 7 April 2008

- ^ "Sickness halts Omagh trial". The Guardian. 2006-09-06. http://www.guardian.co.uk/Northern_Ireland/Story/0,,1865911,00.html. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ "Man not guilty of Omagh murders". BBC News Online. 2007-12-20. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/7154221.stm. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ a b "Flanagan apology to bomb families". BBC News. Published 24 January 2008.

- ^ "Landmark damages awarded for N. Ireland bombing". Reuters (India). 2009-06-08. http://in.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idINIndia-40164020090608. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ^ a b c d e f "Nuala O'Loan: the job I didn't want to leave". The Belfast Telegraph. Published 5 November 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Conflict Archive on the Internet. "Statement by the Police Ombudsman for Northern Ireland on her Investigation of matters relating to the Omagh Bomb on 15 August 1998". 2001-12-12. Archived from the original on 2007-02-05. http://web.archive.org/web/20070205065443/http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/police/ombudsman/po121201omagh1.pdf. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ "Justice denied". The Guardian. Published 21 December 2007.

- ^ Johnston, Wesley. "Appendix B: Police Press Releases on the Omagh Bomb". http://www.wesleyjohnston.com/users/ireland/past/omagh/police_press_releases.html. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ a b c d "Families shocked at Omagh report". BBC News. Published 12 December 2001.

- ^ a b c "OMAGH BOMB: PROBE INTO RUC 'WARNING' NEARS END". The Sunday Mirror. Published 7 October 2001.

- ^ "MI5 withheld intelligence ahead of Omagh". RTÉ News. 2006-02-24. http://www.rte.ie/news/2006/0224/omagh.html. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ Omagh agent claims Garda let bomb pass The Guardian. Published October 19, 2003.

- ^ a b MI5 "did not retain Omagh advice" BBC News. Published 1 March 2006.

- ^ "Omagh bomb investigation review". BBC News. Published 7 February 2008.

- ^ "Orde to outline the extent of dissident threat". The Belfast Telegraph. Published 7 February 2008.

- ^ a b c Beginnings. Omagh Support and Self Help Group. Accessed 18 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d Omagh - Drama. Channel 4. Accessed 18 February 2009.

- ^ "Omagh support group launch digital archive". The Ulster Herald. Published March 29, 2007.

- ^ "Omagh families' vigil at 'fundraiser'". BBC News. Published 26 November 2000.

- ^ a b "Omagh families head to international courts". BBC News. Published 10 April 2000.

- ^ "Living with the Omagh legacy" BBC News. Published 22 January 2002.

- ^ a b c "Fury as Blair snubs Omagh families". The Guardian. Published 17 February 2002.

- ^ a b c d Def Leppard Rock Of Ages - Songs. Def Leppard Tour History. Accessed 18 February 2009.

- ^ a b c d U2: U2faqs.com - Songs / Lyrics FAQ. U2faqs.com Accessed 18 February 2009.

- '^ "Closer to the Edge". Irish Times. Published October 21, 2000. (Archived at @U2. Accessed 18 February 2009.)

- ^ U2 (2003). U2 Go Home: Live from Slane Castle (Concert DVD). Slane Castle, Ireland.

- ^ "Omagh bereaved 'not let down'". BBC News. Published 8 March 2000.

- ^ a b c d e f "Omagh memorial in inscription row". BBC News. Published 18 September 2007.

- ^ a b c d A monument that casts a human light. By Fintan O'Toole. Irish Times. Published September 22, 2007. (Archived at Seán Hillen's website. Accessed 18 February 2009)

- ^ "Omagh memorial lifted into place". News Letter. Published 28 July 2008. Accessed 1 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d Omagh marks 10th anniversary of deadly bombing. By Rachel Stevenson. The Guardian. Published 15 August 2008. Accessed 18 February 2009.

External links

- Bombing Memorial Website

- The Omagh Bomb - List of Those Killed (CAIN)

- Omagh Support and Self Help Group

- Reflections on Omagh bombing from five years on

- La bomba di Omagh (Italian)

The Troubles Participants in the Troubles Chronology Political Parties Republican

paramilitariesSecurity forces of the United Kingdom

Loyalist

paramilitaries• Ulster Defence Association

• Ulster Volunteer Force

• Loyalist Volunteer Force

• Red Hand Commandos

• Young Citizen Volunteers

• Ulster Young Militants

• Ulster Resistance

• UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade

Linked to

• Some RUC and British Army members• Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association formed (1967)

• Battle of the Bogside (1969)

• Riots across Northern Ireland (1969)

• Beginning of Operation Banner (1969)

• Social Democratic and Labour Party formed (1970)

• Internment without trial begins with Operation Demetrius (1971)

• Bloody Sunday by British Army (1972)

• Northern Ireland government dissolved. Direct rule from London begins (1972)

• Bloody Friday by Provisional IRA (1972)

• Power sharing Northern Ireland Assembly set up with SDLP and Ulster Unionist Party in power (1973)

• Mountjoy Prison helicopter escape. Three Provisional IRA prisoners escape from Mountjoy Prison by helicopter (1973)

• Ulster Workers' Council strike causes power-sharing Northern Ireland Assembly to end (1974)

• Dublin and Monaghan bombings by UVF with alleged British Army assistance (1974)

• Kingsmill massacre by South Armagh Republican Action Force (1976)

• Warrenpoint Ambush by Provisional IRA (1979)

• 1981 Irish hunger strike by Provisional IRA and INLA members (1981)

• Hunger striker Bobby Sands elected MP. Marks turning point as Sinn Féin begins to move towards electoral politics (1981)

• Maze Prison escape. 38 Provisional IRA prisoners escape from H-Block 7 of HM Prison Maze (1983)

• Brighton hotel bombing by Provisional IRA (1984)

• Anglo-Irish Agreement between British and Irish governments (1985)

• Remembrance Day bombing by Provisional IRA (1987)

• Peace Process begins (1988)

• Operation Flavius, Milltown Cemetery attack and Corporals killings (1988)

• Bishopsgate bombing (1993)

• Downing Street Declaration (1993)

• First Provisional IRA ceasefire (1994)

• Loyalist ceasefire (1994)

• Docklands bombing (1996)

• 1996 Manchester bombing (1996)

• Second Provisional IRA ceasefire (1997)

• Good Friday Agreement (1998) signals the end of the Troubles

• Assembly elections held, with SDLP and UUP winning most seats (1998)

• Omagh bombing by dissident Real IRA (1998)• Unionist parties:

• Democratic Unionist Party

• Northern Ireland Unionist Party

• Ulster Unionist Party

• Progressive Unionist Party

• Conservative Party

• UK Unionist Party

• Traditional Unionist Voice

• Nationalist parties:

• Democratic Left

• Fianna Fáil

• Fine Gael

• Labour Party

• Progressive Democrats

• Sinn Féin

• Social Democratic & Labour Party

• Workers' Party of Ireland

• Irish Republican Socialist Party

• Republican Sinn Féin

• Cross-community parties:

• Alliance Party

• Historically important parties:

• Nationalist Party

• Northern Ireland Labour Party

• Protestant Unionist Party

• Vanguard Unionist Progressive Party

• Northern Ireland Women's Coalition

• People's Democracy

• Republican Labour Party

• Anti H-Block

• Irish Independence Party The Troubles at Wiktionary ·

The Troubles at Wiktionary ·  The Troubles at Wikibooks ·

The Troubles at Wikibooks ·  The Troubles at Wikiquote ·

The Troubles at Wikiquote ·  The Troubles at Wikisource ·

The Troubles at Wikisource ·  The Troubles at Commons ·

The Troubles at Commons ·  The Troubles at WikinewsCategories:

The Troubles at WikinewsCategories:- 1998 in Northern Ireland

- Car and truck bombings in the United Kingdom

- Omagh

- Real Irish Republican Army actions

- Terrorism in Northern Ireland

- Terrorist incidents in 1998

- The Troubles in County Tyrone

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.