- Drumcree conflict

-

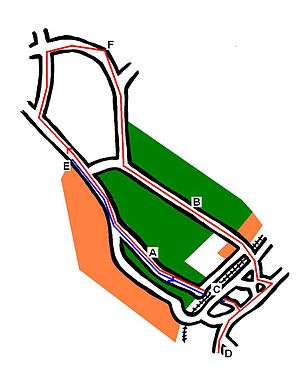

The Drumcree conflict or Drumcree standoff is an ongoing dispute over a yearly parade in the town of Portadown, Northern Ireland. The dispute is between the Orange Order and local residents. The residents are currently represented by the Garvaghy Road Residents Coalition (GRRC); before 1995 they were represented mainly by the Drumcree Faith & Justice Group (DFJG). The Orange Order (a Protestant organisation with strong links to unionism) insists that it should be allowed to march its traditional route to-and-from Drumcree Church (see map). It has marched this route since 1807, when the area was sparsely populated. However, today most of this route falls within the town's mainly-Catholic and nationalist quarter, which is densely populated. The residents have sought to re-route the parade away from this area, seeing it as "triumphalist"[1] and "supremacist".[2] The "Drumcree parade" is held on the Sunday before the Twelfth of July.

There have been intermittent violent clashes during the yearly parade since at least 1873. The dispute was intensified by The Troubles, which began in 1969. Before the 1990s, the most contentious part of the parade was the outward leg along Obins Street. When the parade was banned from Obins Street in 1986, the focus shifted to the parade's return leg along Garvaghy Road. In 1995, the dispute drew the attention of the international media as it led to widespread protests and rioting throughout Northern Ireland. This pattern was repeated every July for the next four years. During this time the dispute led to the deaths of at least five civilians and prompted a massive police and army operation. Since 1998 the parade has been banned from most of the nationalist area, and the violence has subsided. However, regular moves to get the two sides into face-to-face talks have failed.

Contents

Background

Portadown has long been a mainly-Protestant and unionist town. For example, at the height of the conflict in the 1990s, Protestants outnumbered Catholics four-to-one.[4] The town's Catholics and nationalists claim that they have long suffered discrimination, especially in employment.[4] Each summer the town centre is bedecked with unionist flags and symbols.[5] This is to coincide with the "marching season", when numerous Protestant marches take place in the town. Throughout the 20th century, the police force (Royal Ulster Constabulary or RUC) was also almost wholly Protestant and its members were free to join groups such as the Orange Order.[4] According to Peter Mulholland, a Portadown-born anthropologist, this fuelled a strong feeling of isolation among the Catholics and nationalists.[4] He argued that the Orange marches annually "re-invigorate sectarianism" and serve to "re-assert the supremacy" of Protestants and unionists.[4]

Before partition

The Orange Order claims that it was founded after the so-called Battle of the Diamond in September 1795.[6] This was a rural riot that took place near the village of Loughgall, a few miles from Drumcree. Portadown and the wider north Armagh area is thus seen as the birthplace of Orangeism, with many of the Order's oldest lodges based there.[7]

The Order also claims that its modern church parade to Drumcree is held to commemorate the 1916 Battle of the Somme during World War I.[8] However, the march to Drumcree Church was originally and traditionally to celebrate the 1690 Battle of the Boyne. The Orange Order's first ever marches were to celebrate this battle and they took place on 12 July 1796 in Portadown, Lurgan and Waringstown.[9] In July 1795, the year the Orange Order formed, a Reverend Devine had held a "Boyne commemoration" sermon at Drumcree Church.[8] In his History of Ireland Vol I (published in 1809), the historian Francis Plowden described the events that followed this sermon:

[Reverend Devine] so worked up the minds of his audience, that upon retiring from service, on the different roads leading to their respective homes, they gave full scope to the anti-papistical zeal, with which he had inspired them... falling upon every Catholic they met, beating and bruising them without provocation or distinction, breaking the doors and windows of their houses, and actually murdering two unoffending Catholics in a bog. This unprovoked atrocity of the Protestants revived and redoubled religious rancour. The flame spread and threatened a contest of extermination...

The first official Orange Order parade to and from Drumcree Church took place in July 1807. Each July since then, the Orangemen have paraded from the centre of town, along Obins Street, to Drumcree Church, and returned along Garvaghy Road.[7] In the early 19th century, the area between the town and church was mostly fields. Protestant parades would regularly march through this area and past the Catholic Church.[10] In 1835, Armagh magistrate William Hancock (a Protestant) wrote:

For some time past the peaceable inhabitants of the parish of Drumcree have been insulted and outraged by large bodies of Orangemen parading the highways, playing party tunes, firing shots and using the most opprobrious epithets they could invent. [The Orangemen have gone] a considerable distance out of their way to pass a Catholic chapel on their march to Drumcree church.[8]

There was violence during the Drumcree parades in 1873, 1883, 1885, 1886, 1892, 1903, 1905, 1909 and 1917.[13] [14]

After partition

After the partition of Ireland in 1921, the Northern Ireland government's policy tended to favour Protestant and unionist parades. From 1922 to 1950, almost 100 parades and meetings were banned under the Special Powers Act – nearly all were Irish nationalist or republican.[15] Although violence died down during this period, there were clashes at the 1931 and 1950 Drumcree parades.[13] The Public Order Act 1951 exempted 'traditional' parades from having to ask police permission, but 'non-traditional' parades could be banned or re-routed without appeal. Again, the legislation tended to benefit Protestant parades.[16]

In the 1950s and 1960s, a number of housing estates were built on the fields along Garvaghy Road.[8] In 1969, Northern Ireland was plunged into a conflict known as the "The Troubles". Portadown, which had been religiously mixed, underwent major population shifts.[8] The result was that these new estates became almost wholly Catholic and nationalist, while the rest of the town became almost wholly Protestant and unionist.[8] After the outbreak of the conflict, the Grand Orange Lodge encouraged Orangemen to join the Northern Ireland security forces—namely the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and the British Army's Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR). The response from Orangemen was strong.[17] Irish nationalists and republicans, meanwhile, were opposed to the security forces.

1972

In 1972, during the first years of the troubles, residents of Portadown's mainly Catholic nationalist enclave mobilised under the banner of 'Portadown Resistance Council'. They called for the parade to be re-routed away from Obins Street (see map), which was where most of the residents lived at the time.[18] The Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) warned that it would "take action" if the Orange Order marched along Obins Street on 12th July.[18] The Ulster Defence Association (a then-legal loyalist vigilante and paramilitary group) threatened to take counter-action if anything was done to stop the march.[18][19] On Saturday 1 July, nationalists set up barricades at all roads leading into the nationalist area.[20]

On the morning of Sunday 9 July, the army cleared the barricades and used CS gas and rubber bullets on those protesting against the march.[13][20] Once the area was secured, they then allowed Orangemen to parade along the road escorted by at least fifty UDA members.[13][18][21][22] Photographs show the UDA members dressed in paramilitary uniforms and saluting the Orangemen as they marched along Obins Street on their way to Drumcree Church. With all opposition effectively suppressed the parade itself passed peacefully. However, three men were shot dead in Portadown later that day and overnight. A UDA member shot dead two civilians inside McCabe's Bar on High Street. One was the Catholic pub-owner (Jack McCabe) and the other a Protestant customer (William Cochrane). Both men were shot in the head from close range. The gunman was a former RUC officer. When sentenced to life imprisonment for the murders, there were shouts of "keep up the fight!" from about a dozen people in the court's public gallery.[23] Nationalist/republican gunmen are believed to have shot dead a Protestant (Paul Beattie) in the early hours of the next morning in Churchill Park, a housing estate on Garvaghy Road.[24] On 15 July, a Catholic civilian was kidnapped, beaten and shot dead by the UDA in a mainly-loyalist area of the town. His body was found on 4 August in a drain near Watson Street. He had been a long-time member of St Patrick's Accordion Band based on Obins Street.[25]

Later in the month, the Provisional IRA detonated a bomb on Woodhouse Street, and loyalists detonated a bomb at a Catholic church.[13] In the Obins Street area there was also a gun battle involving the Provisional IRA, the UDA, and the security forces.[13] The UDA’s involvement in the 1972 parades made a lasting impression on Portadown nationalists.[26]

1980s: Obins Street

1985

On 17 March (Saint Patrick's Day) the Saint Patrick's Accordion Band (a local nationalist band) was given permission to parade a two-mile 'circuit' of the nationalist area.[20][27] However, a small part of the route (about 150 yards of Park Road) was lined with Protestant and unionist owned houses.[20] Arnold Hatch, the town's mayor and Ulster Unionist Party councillor, demanded that the march be banned.[20][27][28] When the RUC let it go ahead, Hatch and a small group of unionists staged a sit-down protest on Park Road.[27] The RUC forced the band to turn around.[27][28] That evening, the band again tried to march the route. Even though the protestors had gone, the RUC again stopped the band.[20] Following this incident, Portadown nationalists boosted their campaign to get Orange parades banned from Obins Street.[28] Social Democratic and Labour Party politician Bríd Rodgers described this incident as pivotal in the escalation of the parade dispute.[27]

Shortly before the Drumcree parade of 7 July, hundreds of nationalists staged a sit-down protest on Obins Street. However, police violently removed the protestors and allowed the parade to continue.[28] At least one man was beaten unconscious and many were arrested.[20] The whole length of Garvaghy Road was lined with British Army and police vehicles for the parade's return leg.[20] On 12 July, eight Orange lodges met at Corcrain Orange Hall and tried to march through Obins Street to the town centre. When they were blocked by police, hundreds of loyalists gathered at both ends of the road and tried to push through.[28] At least 52 police and 28 rioters were wounded, while about 50 Catholic-owned buildings were attacked.[28] After this, the police erected a barrier at each end of Obins Street.[28]

In July 1985, residents of the nationalist district formed a People Against Injustice Group, later renamed the Drumcree Faith & Justice Group (DFJG).[4] It quickly became the main group representing the residents. The DFJG sought to explain to Orangemen how residents felt about the marches and to improve cross-community relations.[29] It organized peaceful protests, issued newsletters and held discussions with the RUC. It also made unsuccessful attempts to hold discussions with the Orangemen.[4]

1986

The Apprentice Boys, a Protestant fraternity similar to the Orange Order, had planned to march along Garvaghy Road on 1 April (Easter Monday). The day before, police decided to ban the march as it believed the UDA were to take part.[28] At 1:00am on Monday, at least 3000 men gathered in the town centre, forced their way past a small group of police, and marched along Garvaghy Road.[20] Among them was Ian Paisley,[20] leader of the Democratic Unionist Party and of the fundamentalist Free Presbyterian Church. Residents claimed that some of the marchers were carrying guns.[28] Some of the marchers attacked houses along the route and residents claimed that the RUC did little or nothing to stop this.[20] There followed rioting between residents and the RUC. Some set up barricades for fear of further attacks.[20] There was a feeling among locals that the RUC had "mutinied" and refused to enforce the ban.[20] Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams said that it was "more evidence of the untrustworthiness of the RUC".[20] In the afternoon, another Apprentice Boys parade marched through the town centre. A group of loyalists attacked police, who were blocking access to the nationalist area. One rioter, Keith White, was shot by a plastic bullet and died in hospital on 14 April.[28][30]

On 6 July the Drumcree parade took place. An estimated 4000 British Army and RUC were deployed in the town.[20] The RUC said that the Orange Order had allowed "known troublemakers" to take part in the march, contrary to a prior agreement.[31] Among the marchers was George Seawright, a unionist politician and Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) member who publicly proposed burning Catholics in ovens.[31] As the march entered the nationalist district, the RUC seized Seawright and other known militants. The Orangemen attacked the officers with stones and other missiles.[31] Along the parade's route (Obins Street and Garvaghy Road), local residents were prevented from leaving their homes.[28] Both nationalists and loyalists attacked police, wounding at least 27.[28]

The 12 July parade was blocked from Obins Street for the second year. Instead, police escorted the parade along Garvaghy Road without any bands.[28] Although there was little violence on Garvaghy Road, loyalists later rioted with police and tried to smash through the barrier leading to Obins Street.[28]

In 1987 the Public Order Act was repealed by the Public Order (Northern Ireland) Order 1987, which removed the special status of 'traditional' parades.[32] This meant that, after 1986, Orange parades were effectively banned from Obins Street indefinitely.[28][33] The July 1987 parade was re-routed and 3000 soldiers and 1000 police were sent to keep order.[33] In the minds of the Orangemen, sacrificing the Obins Street leg meant that they would be guaranteed the Garvaghy Road leg.[33] Although the Garvaghy Road leg had caused trouble before, it was less populated than Obins Street in 1987.

1990s: Garvaghy Road

A mural supporting the Portadown Orangemen on Shankill Road, Belfast. On the left of the picture is a UDA/UFF flag.

A mural supporting the Portadown Orangemen on Shankill Road, Belfast. On the left of the picture is a UDA/UFF flag.

Although nearly ten years passed without serious conflict over the Drumcree parades, both sides remained unhappy with the situation. Despite reluctantly accepting the new route, the Orangemen continued to apply for a march along Obins Street each year.[34] Meanwhile, residents of Garvaghy Road and the surrounding nationalist district (see map) were very unhappy about what they called "triumphalist" Orange parades through their area. They made their opposition known in a number of ways: through the tenants' associations that represented each housing estate, through the Drumcree Faith & Justice Group (DFJG), and through local politicians.

Lead-up to July 1995

In 1994, the Provisional IRA and loyalist paramilitaries called ceasefires.

In May 1995 the Garvaghy Road Residents Coalition (GRRC) was formed, comprising representatives from the DFJG and the tenants' associations.[35] Its main goal was to divert Orange marches away from Garvaghy Road through peaceful means. It held peaceful protests, petitioned the RUC and government ministers, and tried to draw media attention to the dispute.[4] The GRRC held regular public meetings with the residents and there were usually about 12 representatives on the GRRC at any one time.[35] According to one of its members, Joanne Tennyson, "Although the GRRC could speak to anyone they wanted, at the end of the day no-one in the committee had the right to say we would do anything, not even ... the spokesman. The community had to agree as a whole and that was the purpose of holding public meetings".[35] The GRRC's first secretary and spokesman was Eamon Stack, a Jesuit priest and DFJG member who had lived in the area since 1993. Fr Stack emphasized that the GRRC was non-sectarian and was not connected to any political parties. He would remain its spokesman until after July 1997.[35]

By the mid 1990s, the population of Portadown was about 70% Protestant and 30% Catholic. There were three Orange halls in the town and an estimated 40 loyalist marches each summer.[36]

1995

On Sunday 9 July 1995, hundreds of nationalist residents staged a sit-down protest on Garvaghy Road to block the march.[37] Although the parade was legal and the protest was not, police prevented the parade from taking the Garvaghy Road route. The Orangemen refused to take an alternate route, announcing that they would stay at Drumcree Church until they were allowed to continue. The Orangemen refused to negotiate with the residents' group and the Mediation Network was called upon to intercede.[4] The RUC and local politicians were also involved in trying to resolve the deadlock.

Meanwhile, ~10,000 Orangemen and their supporters were engaged in a standoff with ~1,000 police at Drumcree Church.[38] During this standoff, missiles were continuously thrown at the police, who responded by firing 24 plastic bullets.[38] In support of the Orangeman, loyalists blocked numerous roads across Northern Ireland, and sealed off the port of Larne.[38] On the evening of Monday 10 July, Ian Paisley (Democratic Unionist Party leader) and David Trimble (Ulster Unionist Party leader) held a rally at Drumcree Church. Afterwards they gathered a number of Orangemen and tried to push through the police barricade, but were taken away by officers.[38]

By the morning of Tuesday 11 July, a compromise was reached. The Orangemen would be allowed to march along Garvaghy Road on condition that they did so silently, without accompanying bands. GRRC member Breandán Mac Cionnaith says that the agreement was that the parade would go silently along the road, on condition that future parades would only occur with the consent of residents.[39] This claim is not verified by other parties.[40] The protesters were eventually persuaded to clear the road, and the march went ahead. However, as they reached the end of Garvaghy Road, Paisley and Trimble held their hands in the air in what appeared to be a gesture of triumph.[38] Trimble claims that he only took Paisley's hand to prevent the DUP leader from taking all the media attention.[41]

Both sides were deeply unhappy with the events of July 1995. Residents were angered that the parade had gone ahead and at what they saw as unionist triumphalism, while Orangemen and their supporters were angered that their parade had been held up by an illegal protest. Some Orangemen formed a group called Spirit of Drumcree (SoD) to defend their "right to march". At a SoD meeting in Belfast's Ulster Hall one of the platform speakers said, to applause, that

"Sectarian means you belong to a particular sect or organisation. I belong to the Orange Institution. Bigot means you look after the people you belong to. That's what I'm doing. I'm a sectarian bigot and proud of it.'[42]

1996

On Saturday 6 July 1996, the Chief Constable stated that the parade would be banned from marching along Garvaghy Road.[43] Police checkpoints and barricades were set-up on all routes into the nationalist area.

On Sunday 7 July the parade gathered at Drumcree Church and was blocked by police barricades. At least 4,000 Orangemen and their supporters began another standoff. That afternoon, Reverend Martin Smyth (then Orange Grand Master) arrived at Drumcree and announced that there could be "no compromise".[44] Again, loyalists began riots and blocked hundreds of roads across Northern Ireland.

On the night of 7 July, Catholic taxi-driver Michael McGoldrick was shot dead near Lurgan by the Mid Ulster Brigade of the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).[45] It is believed the killing was ordered by the brigade's leader, Billy Wright, from Portadown.[8] Wright was frequently to be seen at Drumcree with Harold Gracey, head of the Portadown Orange Lodge.[8] Members of the brigade smuggled homemade weaponry to Drumcree, apparently unhindered by the Orangemen.[8] Allegedly, the brigade also had plans to drive petrol tankers into the Garvaghy area and ignite them.[46] The following month, Wright and the Portadown unit of the Mid-Ulster Brigade were stood down for breaking the ceasefire. Wright took the unit with him and formed a breakaway group called the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) and began a campaign of sectarian killing.

On Wednesday 10 July, the RUC reported that, over the previous four days, there had been:

- 100 incidents of intimidation

- 758 attacks on the police

- 90 civilians injured

- 50 police injured

- 662 plastic bullets fired by the police

- 156 arrests made[44]

At noon on Thursday 11 July, the Chief Constable reversed his decision and allowed the parade to march along Garvaghy Road. Residents of Garvaghy Road had not been consulted on this.[44] Rioting erupted immediately as police violently removed protestors from Garvaghy Road, often after beating them.[44] Rioting also erupted in nationalist areas of Lurgan, Armagh, Belfast and Derry.[44] In Derry, twenty-two protestors were seriously injured and one, Dermot McShane, died after being run-over by a British Army armoured vehicle.[44] Rioting continued throughout the week, during which time the RUC fired a total of 6002 plastic bullets, 5000 of which were directed at nationalists.[44]

The Committee on the Administration of Justice (CAJ), who had sent members to observe the situation, condemned this "completely indiscriminate" use of plastic bullets.[44] Following the events, leaders of both Sinn Féin and the SDLP stated that nationalists had completely lost faith in the RUC as an impartial police force.[44]

1997

Main article: 1997 nationalist riots in Northern Ireland Battlehill LOL 395, from Portadown, at a small parade in nearby Tandragee.

Battlehill LOL 395, from Portadown, at a small parade in nearby Tandragee.

In late June 1997, Secretary of State Mo Mowlam had privately decided to let the parade proceed. This was later revealed in a leaked Northern Ireland Office document.[47] However, in the days leading up to the parade, she insisted that no decision had been made.[47]

Women from the nationalist district set-up a peace camp along the Garvaghy Road.[47] On Thursday 3 July, the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF) threatened to kill Catholic civilians if the march was not allowed to proceed.[47] The following day, sixty families had to be evacuated from their homes on Garvaghy Road after a loyalist bomb threat.[48] The Ulster Unionist Party also threatened to withdraw from the Northern Ireland peace process.[49]

On Sunday 6 July at 3:30am, 1500 soldiers and police moved into the nationalist area and sealed-off all the roads.[47] This led to clashes with around 300 protestors. From this point onward, all residents were prevented from leaving their housing estates and accessing the main road.[47] As residents were also unable to reach the Catholic church, the local priests were forced to hold an open-air mass in front of a line of soldiers and armoured personnel carriers.[47]

The parade marched along Garvaghy Road at noon that day. After it passed, the security forces began withdrawing from the area. A large-scale riot developed. About 40 plastic bullets were fired at rioters, and about 18 people were taken to hospital.[47] In nearby Lurgan, nationalist protestors stopped a train and set it alight, while fierce riots erupted in several nationalist areas. Several RUC and Army patrols came under fire, specially in North and West Belfast. The widespread violence lasted until 10 July, when the Orange Order decided unilaterally to re-route six parades. The following day, Orangemen and residents agreed to waive another march in Newtownbutler, County Fermanagh.[47]

In 1997, Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams told an RTÉ journalist of his party's involvement in the dispute:

Ask any activist in the north, ‘did Drumcree happen by accident?', and he will tell you, ‘no'. Three years of work on the lower Ormeau Road, Portadown and parts of Fermanagh and Newry, Armagh and in Bellaghy and up in Derry. Three years of work went into creating that situation and fair play to those people who put the work in. They are the type of scene changes that we have to focus on and develop and exploit.[50][51][52]

After July 1997, GRRC member Brendan McKenna (Irish: Breandán Mac Cionnaith) replaced Eamon Stack as the group's spokesman. Mac Cionnaith had been convicted and imprisoned for his involvement in a 1981 IRA bomb attack on Portadown's Royal British Legion hall. He was released in 1984.[8][35]

1998

Early in 1998 the Public Processions Act was passed, establishing the Parades Commission. The Commission was now responsible for deciding what route marches should take. On 29 June 1998, the Parades Commission decided to ban the parade from Garvaghy Road.[53]

On Friday 3 July about 1000 soldiers and 1000 police were deployed in the area.[53] They built large barricades across all roads leading into the nationalist area. In the fields between Drumcree Church and the Garvaghy area they also dug a trench (fourteen feet wide),[54] which was then lined with rows of barbed wire.[53] Soldiers also occupied Drumcree College, St John the Baptist Primary School, and some houses close to the barricades.[55]

On Sunday 5 July the Orangemen arrived at Drumcree Church and stated that they would remain there until they were allowed to proceed.[53] A group calling itself "Portadown Action Command" issued a statement which read:

As from midnight on Friday 10th July 1998, any driver of any vehicle supplying any goods of any kind to the Gavaghy Road will be summarily executed.[8]

There was widespread loyalist violence across Northern Ireland. Over the next ten days, 2,561 "public order incidents" were recorded,[53] this included:[53]

- 144 houses attacked (the vast majority owned by Catholics and/or nationalists)

- 165 other buildings attacked (the vast majority owned by Catholics and/or nationalists)

- 178 vehicles hijacked

- 467 vehicles damaged

- 615 attacks on members of the security forces (including 24 shooting incidents)

- 76 police offices injured

- 632 petrol bombs thrown

- 837 plastic bullets fired by security forces

- 284 people arrested

On Sunday 12 July at 4:30am, Jason (aged 8), Mark (aged 9) and Richard Quinn (aged 10) were burnt to death when their home was firebombed by loyalists.[53] The boys' mother was a Catholic, and their home was in a mainly-Protestant part of Ballymoney. Following the murders, William Bingham (County Grand Chaplain of Armagh and member of the Orange Order negotiating team) said that "walking down the Garvaghy Road would be a hollow victory, because it would be in the shadow of three coffins of little boys who wouldn't even know what the Orange Order is about". He said that the Order had lost control of the situation and that "no road is worth a life".[56] However he later apologised for implying that the Order was in any way responsible for the deaths.[57]

The murders provoked widespread anger and calls for the Orange Order to end their protest at Drumcree. Although the number of Orangemen dropped greatly, the Portadown lodges voted unanimously to continue their standoff.[53]

On Wednesday 15 July at 6:30am the RUC began a search operation in the fields at Drumcree. A number of weapons were uncovered in the search, including: a home-made machine gun, ammunition, explosive devices, and crossbows with home-made explosive arrows.[53]

1999

In the year after July 1998, the Orange Order and GRRC tried to resolve the dispute through "proximity talks" using go-betweens. The Orangemen refused to talk directly to the GRRC. Some senior Portadown Orangemen claim that they had been promised a parade on Garvaghy Road later that year if they could control things on the traditional parading dates.[58]

- March to June

On 14 March 1999, the Parades Commission said that the upcoming march would again be banned from Garvaghy Road. The following day the GRRC's legal advisor, Rosemary Nelson, was assassinated in Lurgan. The killing was claimed by the "Red Hand Defenders", who had detonated a bomb under her car.[59]

In April 1999, Portadown loyalists threatened to mount a picket of St John's Catholic Church at the top of Garvaghy Road. On 29 May a 'junior' Orange march passed near Garvaghy Road. There were clashes following the march with 13 RUC officers and four civilians hurt. The RUC fired 50 plastic bullets during the clashes.[59]

- July

The 1999 Drumcree march took place on Sunday 4 July. The security forces had again blocked all roads leading into the nationalist area with large steel barricades. Although some missiles were thrown at Drumcree church, the protest there was calm compared to last year.[59]

The barricades were removed on 14 July.[59] On 28 July, a 15-year-old Catholic boy was attacked as Orangemen removed their arch at the end of Garvaghy Road. He was allegedly beaten by loyalists within yards of two RUC landrovers.[60]

On 31 July, a loyalist wielding an AK-47 and a handgun walked along Craigwell Avenue (a street of Catholic-owned houses) firing shots. He was wrestled to the ground and arrested. In August, the street was evacuated after a hoax bomb alert, and the houses were attacked with breeze blocks.[61]

Also that year, the GRRC published a book detailing the history of Orange parades in the area. The book was called Garvaghy: A Community Under Siege.

2000

- April to June

In April 2000, a newspaper reported that Portadown Orangemen had threatened PM Tony Blair, saying that if that year's march was banned from Garvaghy Road it would prove to be his "Bloody Sunday".[62] The following month, almost 200 masked loyalists attacked Catholic-owned houses on Craigwell Avenue after assembling at Carlton Street Orange Hall. Allegedly RUC landrovers were nearby but did not intervene.[63] On 27 May, the nationalist area was sealed-off so that a 'junior' Orange parade could march along the lower end of Garvaghy Road. The march included men in paramilitary uniform.[63]

On 31 May, a children's cross-community concert at St John's Catholic Church was disrupted by Portadown Oangemen beating Lambeg drums, allegedly trying to drown it out. Present at the concert were Secretary of State Peter Mandelson and UUP leader (and Orangeman) David Trimble.[63] After the concert, teachers, parents, children and guests headed for a reception at the Protestant Portadown College. They were met by a 300-strong loyalist mob who hurled missiles and sectarian abuse while preventing families from leaving the hall. The security forces were deployed but did not disperse the mob or make arrests.[63] On 7 June, St John's Catholic Church was set alight by arsonists.[64]

On 16 June, Catholic workers at Denny's factory in Portadown walked-out after placards carrying sectarian slogans were erected near the main entrance. The week before, loyalists had thrown missiles at Catholics leaving the factory. The placards were removed shortly after.[64] Later in the month, loyalists sent death threats to workers who were reinforcing the security barrier (or "peace line") along Corcrain Road. The work stopped, leaving the nationalist area vulnerable to attack.[64]

- July

In July, it was revealed that members of Neo-Nazi group Combat 18 were travelling from England to join the Orangemen at Drumcree. They were given shelter by LVF members in Portadown and Tandragee.[65] That month, Portadown Orangeman Ivan Hewitt (who sported Neo-Nazi tattoos) warned in a TV documentary that it may be time for loyalists to "bring their war to Britain".[66]

The 2000 Drumcree march took place on Sunday 2 July. It was again banned from Garvaghy Road and the nationalist area was sealed-off with barricades. Speaking after the march was stopped, District Master Harold Gracey called for widespread protests across Northern Ireland.[67] Stoneyford Orangeman Mark Harbinson, who was associated with the paramilitary Orange Volunteers, had earlier proclaimed that "the war begins today".[67] On Monday 3 July a crowd of over fifty loyalists, led by UDA commander Johnny Adair, appeared at Drumcree with a banner bearing "Shankill Road UFF" [Ulster Freedom Fighters]. In the Corcrain area, LVF gunmen fired a volley of shots in the air for Adair and a cheering crowd.[67] On Tuesday 4 July, security forces used water cannon against protestors at the Drumcree barricade – their first deployment in Northern Ireland for over 30 years.[67]

In an interview on 7 July, Harold Gracey refused to condemn the violence linked to the protests, saying "Gerry Adams doesn't condemn violence so I'll not".[67] On 9 July, the RUC warned that loyalists had threatened to "kill a Catholic a day" until the Orangemen were allowed to march along Garvaghy Road.[66] Two days later, a group of 150–200 loyalists ordered all shops in Portadown's town centre to shut. Along with another group, they then tried to march on Garvaghy Road from both ends, but were held back by the RUC. That night, 21 RUC officers were hurt during clashes with loyalists.[66]

On 14 July, Portadown Orangemen's calls for another day of widespread protest went unheeded as the Armagh and Grand Lodges refused to support their calls. Businesses remained open and only a handful of roads were blocked for a short time. The security barriers were removed and soldiers returned to barracks.[66]

2001 onward

Since July 1998, the Orangemen have applied to march the traditional route every Sunday of the year – both the outward leg via Obins Street (which has been banned since 1986) and the return leg via Garvaghy Road.[68][69][34][70] They have also held a small protest at Drumcree Church every Sunday since then.[71] Their proposals have been rejected by the Parades Commission.

In February 2001, loyalists held protests on the lower Garvaghy Road as part of the run-up to "day 1000" of the standoff. The GRRC said that up to 300 people, some masked and armed with clubs, intimidated people living on Garvaghy Road. Some protesters also attacked a car with four women inside.[72]

There was further violence in May 2001. On 5 May, 300 Orangemen and supporters tried to march on to Garvaghy Road but were stopped by RUC. There were some scuffles between Orangemen and RUC officers. District Master Harold Gracey drew controversy when he said to the RUC officers: "We all know where you come from...you come from the Protestant community, the vast majority of you come from the Protestant community and it is high time that you supported your own Protestant people".[73] On 12 May there were clashes between loyalists and nationalists on Woodhouse Street. On 27 May there were clashes between nationalists and the RUC after a "junior" Orange march on the lower Garvaghy Road.[73]

Four days before the July 2001 Drumcree march, 200 supporters and members of the UDA/UFF rallied at Drumcree. The Portadown Orange Lodge claimed that it was powerless to stop such people from gathering and that they could not be held responsible for their actions. Nevertheless, David Jones (the Lodge's spokesman) said that he welcomed any support. Bríd Rogers, a local SDLP MLA, called this "a further example" of Jones's "double standards". She said that Jones's lodge would not speak to the GRRC because of Mac Cionnaith's "terrorist past", yet "he is quite happy to associate with people who have a terrorist present".[74] The march passed off peacefully under a heavy security presence.[75]

Since 2001 Drumcree has been relatively calm, with outside support for the Portadown lodges' campaign declining and the violence lessening greatly. Mac Cionnaith said that he believes the conflict is essentially over.[76] The Orange Order continues to campaign for the right to march on Garvaghy Road.

Map

Routes of the Protestant parades before they were banned from Obins Street (A) in 1986.

Red line: Route taken by Orangemen on the Sunday before 12 July; from their Carlton Street Hall (D) under the railway bridge (C) along Obins Street (A) to Drumcree Church (F) and back along Garvaghy Road (B).

Blue line: Route taken on 12 July; from Corcrain Hall (E) along Obins Street (A) and under the railway bridge (C).

Green areas are largely nationalist/Catholic.

Orange areas are largely unionist/Protestant.References

- ^ "Drumcree tension eases". BBC News. 13 May 1999.

- ^ "Big changes in character of Drumcree dispute". Irish Independent. 3 July 1998.

- ^ "Anger as arch on Garvaghy Road is painted". Portadown Times (17 July 2009)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mulholland, Peter. "Drumcree: A Struggle for Recognition". Irish Journal of Sociology, Vol. 9. 1999.

- ^ BBC (2007-06-06). "Portadown edging towards change". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/northern_ireland/6720063.stm. Retrieved 2010-05-22.

- ^ "Portadown District LOL No.1". Portadown District LOL No.1. http://www.portadowndistrictlolno1.co.uk/Battle_of_the_Diamond.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ a b Dominic Bryan. Drumcree and the "Right to March": Orangeism, Ritual and Politics in Northern Ireland, in T G Fraser, ed., The Irish Parading Tradition: Following the Drum, Houndmills 2000, p.194.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k McKay, Susan. Northern Protestants: An Unsettled People - Portadown. Blackstaff Press (2000).

- ^ McCormack, W J. The Blackwell Companion to Modern Irish Culture. Wiley-Blackwell, 2001. Page 317.

- ^ Bryan, p.195.

- ^ http://orangecitadel.blogspot.com/

- ^ http://orangecitadel.blogspot.com/

- ^ a b c d e f Bryan, Fraser, Dunn. Political Rituals: Loyalist Parades in Portadown - Part 3 - Portadown and its Orange Tradition. CAIN

- ^ http://orangecitadel.blogspot.com/

- ^ Laura K. Dohohue, 'Regulating Northern Ireland: The Special Powers Acts, 1922-1972', The Historical Journal, 41, 4 (1998), p.1093.

- ^ Neil Jarman and Dominic Bryan, 'Green Parades in an Orange State: Nationalist and Republican Commemorations and Demonstrations from Partition to the Troubles, 1920-1970', in T.G. Fraser, ed., The Irish Parading Tradition: Following the Drum, London and New York, 2000, p.102.

- ^ "Memorial to honour the Orange victims". Portadown Times. 27 April 2007. Retrieved on 1 April 2011.

- ^ a b c d Kaufmann, Eric P. The Orange Order: a contemporary Northern Irish history. Oxford University Press, 2007. p 154.

- ^ Belfast Telegraph, 11 July 1972, p.1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Mulholland, Peter. Two-Hundred Years in the Citadel. 2010.

- ^ Belfast Telegraph, 12 July 1972, p.4.

- ^ Bryan, Dominic. Orange parades: the politics of ritual, tradition, and control. Pluto Press, 2000. Page 92.

- ^ McKittrick, David. Lost Lives. Mainstream, 1999. p.219

- ^ "Malcolm Sutton, ''An Index of Deaths from the Conflict in Ireland'' - 1972". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/sutton/chron/1972.html. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ McKittrick, p.225

- ^ Mervyn Jess. The Orange Order. Dublin, 2007. p.101

- ^ a b c d e Kaufmann. p 155.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Bryan, Fraser, Dunn. Political Rituals: Loyalist Parades in Portadown - Part 4 - 1985 & 1986. CAIN

- ^ Organizations: M, Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN)

- ^ "CAIN: Sutton Index of Deaths". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/sutton/chron/1986.html. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ a b c The Calgary Herald, 7 July 1986

- ^ "Public Order (Northern Ireland) Order 1987.". Opsi.gov.uk. http://www.opsi.gov.uk/si/si1987/Uksi_19870463_en_1.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ a b c Kaufmann. p 158.

- ^ a b "Orangemen accuse Parades Commission of 'talking through its hat'" - Portadown Times - 9 March 2010

- ^ a b c d e The Rosemary Nelson Inquiry Report (23 May 2011), pp.71-74

- ^ The Rosemary Nelson Inquiry Report (23 May 2011), p.70

- ^ Mervyn Jess, The Orange Order, Dublin, 2007, p.104.

- ^ a b c d e "CAIN - Events in Drumcree - July 1995". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/parade/develop.htm#1. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ Jess, p.109.

- ^ Jess, pp.109-11.

- ^ Jess, pp.110-1.

- ^ Jess, p.112.

- ^ "CAIN - Statement by the Chief Constable on his decision to re-route the Drumcree Parade - 1996". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. 1996-07-06. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/parade/docs/cc5796.htm. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "CAIN - Events in Drumcree - 1996". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/parade/develop.htm#2. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ Jess, p.114.

- ^ Coogan, Tim. The Troubles: Ireland's Ordeal 1966-1995 and the Search for Peace. Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. Page 517.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "CAIN - Events in Drumcree - July 1997". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/parade/develop.htm#9. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ "CAIN: Chronology of the Conflict 1997". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/othelem/chron/ch97.htm#Jul. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ Jess, p.130.

- ^ Ruth Dudley Edwards, The Faithful Tribe, p.362.

- ^ Hansard (Col 216), 27 October 2009

- ^ "Orange Order troublemak ers need to be disciplined". Irish Independent. 14 July 2002. Retrieved 09 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "CAIN - Events in Drumcree - 1998". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/issues/parade/develop.htm#10. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ Kaufmann, Eric P. The Orange Order: a contemporary Northern Irish history. Oxford University Press, 2007. Page 198.

- ^ "''An Phoblacht'' - Garvaghy Stands Firm (9 July 1998)". Anphoblacht.com. http://www.anphoblacht.com/news/detail/30871. Retrieved 2010-04-19.

- ^ Jess, pp.134-5.

- ^ Jess, p.136.

- ^ Jess, p.139.

- ^ a b c d "CAIN: Chronology of the Conflict: 1999". Cain.ulst.ac.uk. http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/othelem/chron/ch99.htm. Retrieved 2011-03-09.

- ^ Sectarian attacks: May/June/July 1999. Pat Finucane Centre

- ^ Sectarian attacks: August 1999. Pat Finucane Centre

- ^ Sectarian attacks: April 2000. Pat Finucane Centre

- ^ a b c d Sectarian attacks: May 2000. Pat Finucane Centre

- ^ a b c Sectarian attacks: June 2000. Pat Finucane Centre

- ^ McDonald, Henry (2000-07-02). "English fascists to join loyalists at Drumcree". London: The Observer. http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk/2000/jul/02/northernireland.race. Retrieved 2010-12-30.

- ^ a b c d Sectarian attacks: 8-14 July 2000. Pat Finucane Centre

- ^ a b c d e Sectarian attacks: 1-7 July 2000. Pat Finucane Centre

- ^ "Orange plan Christmas Day parade at Drumcree" - Portadown Times - 30 September 2005

- ^ ""Orangemen seek justice in Drumcree march issue" - ''Portadown Times'' - 2 November 2007". Portadowntimes.co.uk. http://www.portadowntimes.co.uk/news/Orangemen-seek-justice-in-Drumcree.3440201.jp. Retrieved 2010-06-15.

- ^ "Police slammed but parade goes off peacefully" - Portadown Times - 10 July 2009

- ^ "Orangemen sceptical over parading report" - Portadown Times - 12 March 2010

- ^ Sectarian attacks: February 2001, Pat Finucane Centre

- ^ a b Sectarian attacks: May 2001, Pat Finucane Centre

- ^ Sectarian attacks: July 2001 (a), Pat Finucane Centre

- ^ Chronology of the Conflict: July 2001, CAIN

- ^ Jess, p.143.

Further reading

- The Parades Commission's Determination in Relation to the Drumcree Church Parade on 5 July 1998

- Dominic Bryan, "Drumcree: An Introduction to Parade Disputes" from his book Orange Parades: The Politics of Ritual, Tradition and Control

- P. Mulholland, "Drumcree: A Struggle for Recognition" from the Irish Journal of Sociology Vol. 9.

- Susan McKay, "Portadown: Bitter Harvest", from her book Northern Protestants: An Unsettled People

- Conflict Archive on the Internet (CAIN): Developments at Drumcree, 1995-2000

Websites of organisations directly involved in the dispute

- Archived version of the Garvaghy Road Residents' Coalition website

- Portadown District LOL No. 1

- Parades Commission

See also

The Troubles Participants in the Troubles Chronology Political Parties Republican

paramilitariesSecurity forces of the United Kingdom

Loyalist

paramilitaries• Ulster Defence Association

• Ulster Volunteer Force

• Loyalist Volunteer Force

• Red Hand Commandos

• Young Citizen Volunteers

• Ulster Young Militants

• Ulster Resistance

• UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade

Linked to

• Some RUC and British Army members• Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association formed (1967)

• Battle of the Bogside (1969)

• Riots across Northern Ireland (1969)

• Beginning of Operation Banner (1969)

• Social Democratic and Labour Party formed (1970)

• Internment without trial begins with Operation Demetrius (1971)

• Bloody Sunday by British Army (1972)

• Northern Ireland government dissolved. Direct rule from London begins (1972)

• Bloody Friday by Provisional IRA (1972)

• Power sharing Northern Ireland Assembly set up with SDLP and Ulster Unionist Party in power (1973)

• Mountjoy Prison helicopter escape. Three Provisional IRA prisoners escape from Mountjoy Prison by helicopter (1973)

• Ulster Workers' Council strike causes power-sharing Northern Ireland Assembly to end (1974)

• Dublin and Monaghan bombings by UVF with alleged British Army assistance (1974)

• Kingsmill massacre by South Armagh Republican Action Force (1976)

• Warrenpoint Ambush by Provisional IRA (1979)

• 1981 Irish hunger strike by Provisional IRA and INLA members (1981)

• Hunger striker Bobby Sands elected MP. Marks turning point as Sinn Féin begins to move towards electoral politics (1981)

• Maze Prison escape. 38 Provisional IRA prisoners escape from H-Block 7 of HM Prison Maze (1983)

• Brighton hotel bombing by Provisional IRA (1984)

• Anglo-Irish Agreement between British and Irish governments (1985)

• Remembrance Day bombing by Provisional IRA (1987)

• Peace Process begins (1988)

• Operation Flavius, Milltown Cemetery attack and Corporals killings (1988)

• Bishopsgate bombing (1993)

• Downing Street Declaration (1993)

• First Provisional IRA ceasefire (1994)

• Loyalist ceasefire (1994)

• Docklands bombing (1996)

• 1996 Manchester bombing (1996)

• Second Provisional IRA ceasefire (1997)

• Good Friday Agreement (1998) signals the end of the Troubles

• Assembly elections held, with SDLP and UUP winning most seats (1998)

• Omagh bombing by dissident Real IRA (1998)• Unionist parties:

• Democratic Unionist Party

• Northern Ireland Unionist Party

• Ulster Unionist Party

• Progressive Unionist Party

• Conservative Party

• UK Unionist Party

• Traditional Unionist Voice

• Nationalist parties:

• Democratic Left

• Fianna Fáil

• Fine Gael

• Labour Party

• Progressive Democrats

• Sinn Féin

• Social Democratic & Labour Party

• Workers' Party of Ireland

• Irish Republican Socialist Party

• Republican Sinn Féin

• Cross-community parties:

• Alliance Party

• Historically important parties:

• Nationalist Party

• Northern Ireland Labour Party

• Protestant Unionist Party

• Vanguard Unionist Progressive Party

• Northern Ireland Women's Coalition

• People's Democracy

• Republican Labour Party

• Anti H-Block

• Irish Independence Party The Troubles at Wiktionary ·

The Troubles at Wiktionary ·  The Troubles at Wikibooks ·

The Troubles at Wikibooks ·  The Troubles at Wikiquote ·

The Troubles at Wikiquote ·  The Troubles at Wikisource ·

The Troubles at Wikisource ·  The Troubles at Commons ·

The Troubles at Commons ·  The Troubles at WikinewsCategories:

The Troubles at WikinewsCategories:- Orange Order

- The Troubles in County Armagh

- History of County Armagh

- Riots and civil disorder in Northern Ireland

- Protests in Northern Ireland

- Deaths by firearm in Northern Ireland

- Police brutality in the United Kingdom

- Protest marches

- Marches

- Non-combat military operations involving the United Kingdom

- Royal Ulster Constabulary

- 1972 in Northern Ireland

- 1985 in Northern Ireland

- 1986 in Northern Ireland

- 1995 in Northern Ireland

- 1996 in Northern Ireland

- 1997 in Northern Ireland

- 1998 in Northern Ireland

- 1999 in Northern Ireland

- 2000 in Northern Ireland

- 2001 in Northern Ireland

- 1972 riots

- 1985 riots

- 1986 riots

- 1995 riots

- 1996 riots

- 1998 riots

- 1999 riots

- 2000 riots

- 2001 riots

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.