- Operation Demetrius

-

Operation Demetrius Part of The Troubles and Operation Banner

The entrance to Compound 19, one of the sections of Long Kesh internment campLocation Northern Ireland Objective Arrest of suspected Irish republican paramilitaries Date 9–10 August 1971 – 1975 Executed by  British Army

British Army

Royal Ulster Constabulary

Royal Ulster ConstabularyOutcome 342 people arrested and interned

7,000 civilians displacedCasualties British Army: 1 killed

Republicans: 1 killed

Civilians: 11 killed by British Army

(see Ballymurphy Massacre)Operation Demetrius (or internment as it is more commonly known) began in Northern Ireland on the morning of Monday 9 August 1971. Operation Demetrius was launched by the British Army and Royal Ulster Constabulary and involved arresting and interning (without trial) people accused of being paramilitary members. During the operation, the British Army killed 11 civilians[1] and detained 342 people, leading to widespread protests and rioting. The internment would last from 1971 to 1975.[2]

Contents

Planning

Internment was reintroduced on the orders of the then Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Brian Faulkner. The policy of internment had been used a number of times during Northern Ireland's (and the Republic of Ireland's) history.

In the case brought to the European Commission of Human Rights by the Irish government against the British state it was conceded that Operation Demetrius was planned and implemented from the highest levels of the British Government and that specially trained personnel were sent to Northern Ireland to familiarise the local forces in what became known as the 'five techniques'.[3]

On the initial list, which was drawn up by the Special Branch and MI5, there were 450 names, but only 350 of these rendered themselves available for internment. Key figures on the lists, and many who never appeared on them, were warned before the swoop began. It included leaders of the non-violent civil rights movement such as Ivan Barr and Michael Farrell. But, as Tim Pat Coogan noted,

What they did not include was a single Loyalist. Although the UVF had begun the killing and bombing, this organisation was left untouched, as were other violent Loyalist satellite organisations such as Tara, the Shankill Defence Association and the Ulster Protestant Volunteers. It is known that Faulkner was urged by the British to include a few Protestants in the trawl but he refused.[4]

Aftermath

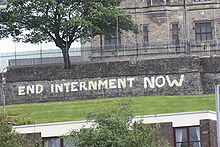

Anti-internment mural in the Bogside area of Derry

The backlash against internment contributed to the decision of the British Government under Prime Minister Edward Heath to suspend the Stormont governmental system in Northern Ireland and replace it with direct rule from Westminster, under the authority of a British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

Following the resignation of the Government of Northern Ireland and the prorogation of the Parliament of Northern Ireland in 1972, internment was continued by the direct rule administration in Northern Ireland until Friday 5 December 1975. During this period a total of 1,981 people were interned: 1,874 were Irish nationalists, while 107 were Ulster loyalists.[5]

Historians generally view that period of internment as inflaming sectarian tensions in Northern Ireland, while failing in its aim of arresting members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army. Many of the nationalists arrested were completely unconnected with the organisation, but had had their names appear on the list of those to be interned through bungling and incompetence and over 100 IRA men escaped arrest.[citation needed] The lack of reliability of the lists and the consequent arrests, complemented by reports of brutality from Long Kesh internment camp led to more people identifying with the IRA in the nationalist community and losing hope in other methods. Following internment, a serving officer of the British Royal Marines declared:

It (internment) has, in fact, increased terrorist activity, perhaps boosted IRA recruitment, polarised further the Catholic and Protestant communities and reduced the ranks of the much needed Catholic moderates.[6]

In terms of loss of life, 1972 was the most violent of the entire Troubles. The fatal march on Bloody Sunday in Derry, when 14 unarmed civil rights protestors were shot dead by British paratroopers, was an anti-internment march.

The effects on domestic and International law

Parker Report

When the interrogation techniques used in Northern Ireland became known to the public, it caused great outrage towards the Government, especially from the Irish nationalist community.

In response to the public and Parliamentary disquiet on 16 November 1971, just over a month after the start of Operation Demetrius, the British Government commissioned a committee of inquiry chaired by Lord Parker, the Lord Chief Justice of England to look into the legal and moral aspects of the use of the five techniques.

The "Parker Report"[7] was published on March 2, 1972 and had found the five techniques to be illegal under domestic law:

- 10. Domestic Law ...(c) We have received both written and oral representations from many legal bodies and individual lawyers from both England and Northern Ireland. There has been no dissent from the view that the procedures are illegal alike by the law of England and the law of Northern Ireland. ... (d) This being so, no Army Directive and no Minister could lawfully or validly have authorized the use of the procedures. Only Parliament can alter the law. The procedures were and are illegal."

On the same day (March 2, 1972), the United Kingdom Prime Minister Edward Heath stated in the House of Commons

- "[The] Government, having reviewed the whole matter with great care and with reference to any future operations, have decided that the techniques ... will not be used in future as an aid to interrogation... The statement that I have made covers all future circumstances".[8]

As foreshadowed in the Prime Minister's statement, directives expressly prohibiting the use of the techniques, whether singly or in combination, were then issued to the security forces by the Government.[8] These are still in force and the use of such methods by UK security forces would not be condoned by the Government.

European Commission of Human Rights

The Irish Government on behalf of the men who had been subject to the five methods took a case to the European Commission on Human Rights (Ireland v. United Kingdom, 1976 Y.B. Eur. Conv. on Hum. Rts. 512, 748, 788-94 (Eur. Comm’n of Hum. Rts.)). The Commission stated that it

- "considered the combined use of the five methods to amount to torture, on the grounds that (1) the intensity of the stress caused by techniques creating sensory deprivation "directly affects the personality physically and mentally"; and (2) "the systematic application of the techniques for the purpose of inducing a person to give information shows a clear resemblance to those methods of systematic torture which have been known over the ages..a modern system of torture falling into the same category as those systems.applied in previous times as a means of obtaining information and confessions."[9][10]

European Court of Human Rights

The Commissions findings were appealed. In 1978 in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) trial "Ireland v. the United Kingdom" (Case No. 5310/71),[11] the facts were not in dispute and the judges court published the following in their judgement:

- These methods, sometimes termed "disorientation" or "sensory deprivation" techniques, were not used in any cases other than the fourteen so indicated above. It emerges from the Commission's establishment of the facts that the techniques consisted of:

- (a) wall-standing: forcing the detainees to remain for periods of some hours in a "stress position", described by those who underwent it as being "spreadeagled against the wall, with their fingers put high above the head against the wall, the legs spread apart and the feet back, causing them to stand on their toes with the weight of the body mainly on the fingers";

- (b) hooding: putting a black or navy coloured bag over the detainees' heads and, at least initially, keeping it there all the time except during interrogation;

- (c) subjection to noise: pending their interrogations, holding the detainees in a room where there was a continuous loud and hissing noise;

- (d) deprivation of sleep: pending their interrogations, depriving the detainees of sleep;

- (e) deprivation of food and drink: subjecting the detainees to a reduced diet during their stay at the centre and pending interrogations.

These were referred to by the court as the five techniques. The court ruled:

- 167. ... Although the five techniques, as applied in combination, undoubtedly amounted to inhuman and degrading treatment, although their object was the extraction of confessions, the naming of others and/or information and although they were used systematically, they did not occasion suffering of the particular intensity and cruelty implied by the word torture as so understood. ...

- 168. The Court concludes that recourse to the five techniques amounted to a practice of inhuman and degrading treatment, which practice was in breach of [the European Convention on Human Rights] Article 3 (art. 3).

On 8 February 1977, in proceedings before the ECHR, and in line with the findings of the Parker report and United Kingdom Government policy, the Attorney-General of the United Kingdom stated that

- "The Government of the United Kingdom have considered the question of the use of the 'five techniques' with very great care and with particular regard to Article 3 (art. 3) of the Convention. They now give this unqualified undertaking, that the 'five techniques' will not in any circumstances be reintroduced as an aid to interrogation."

References

- ^ Internment - A Chronology of the Main Events

- ^ Joint Committee on Human Rights, Parliament of the United Kingdom (2005). Counter-Terrorism Policy And Human Rights: Terrorism Bill and related matters: Oral and Written Evidence. Counter-Terrorism Policy And Human Rights: Terrorism Bill and related matters. 2. The Stationery Office. p. 110. http://books.google.com/books?id=2CRQ6hNzHuAC&pg=PA114.

- ^ Tom Parker Is torture ever justified?

- ^ Tim Pat Coogan The Troubles: Ireland's ordeal 1966-1996 and the search for peace. London: Hutchinson. (Page 126) Internment - Summary of Main Events

- ^ That means approximately 95% of those arrested were from a Catholic background or were Catholics themselves. Internment - Summary of Main Events CAIN part of ARK in collaboration with Queen's University Belfast and University of Ulster

- ^ Hamill, D., Pig in the middle: The Army in Northern Ireland, London, Methuen, 1985

- ^ Report of the committee of Privy Counsellors appointed to consider authorised procedures for the interrogation of persons suspected of terrorism held at CAIN part of ARK in collaboration with Queen's University Belfast and University of Ulster

- ^ a b Ireland v. the United Kingdom Paragraph 101 and 135

- ^ Security Detainees/Enemy Combatants: U.S. Law Prohibits Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment Footnote 16

- ^ David Weissbrodt materials on torture and other ill-treatment: 3. European Court of Human Rights (doc) html: Ireland v. United Kingdom, 1976 Y.B. Eur. Conv. on Hum. Rts. 512, 748, 788-94 (Eur. Comm’n of Hum. Rts.)

- ^ IRELAND v. THE UNITED KINGDOM - 5310/71 (1978) ECHR 1 (18 January 1978)

See also

The Troubles Participants in the Troubles Chronology Political Parties Republican

paramilitariesSecurity forces of the United Kingdom

Loyalist

paramilitaries• Ulster Defence Association

• Ulster Volunteer Force

• Loyalist Volunteer Force

• Red Hand Commandos

• Young Citizen Volunteers

• Ulster Young Militants

• Ulster Resistance

• UVF Mid-Ulster Brigade

Linked to

• Some RUC and British Army members• Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association formed (1967)

• Battle of the Bogside (1969)

• Riots across Northern Ireland (1969)

• Beginning of Operation Banner (1969)

• Social Democratic and Labour Party formed (1970)

• Internment without trial begins with Operation Demetrius (1971)

• Bloody Sunday by British Army (1972)

• Northern Ireland government dissolved. Direct rule from London begins (1972)

• Bloody Friday by Provisional IRA (1972)

• Power sharing Northern Ireland Assembly set up with SDLP and Ulster Unionist Party in power (1973)

• Mountjoy Prison helicopter escape. Three Provisional IRA prisoners escape from Mountjoy Prison by helicopter (1973)

• Ulster Workers' Council strike causes power-sharing Northern Ireland Assembly to end (1974)

• Dublin and Monaghan bombings by UVF with alleged British Army assistance (1974)

• Kingsmill massacre by South Armagh Republican Action Force (1976)

• Warrenpoint Ambush by Provisional IRA (1979)

• 1981 Irish hunger strike by Provisional IRA and INLA members (1981)

• Hunger striker Bobby Sands elected MP. Marks turning point as Sinn Féin begins to move towards electoral politics (1981)

• Maze Prison escape. 38 Provisional IRA prisoners escape from H-Block 7 of HM Prison Maze (1983)

• Brighton hotel bombing by Provisional IRA (1984)

• Anglo-Irish Agreement between British and Irish governments (1985)

• Remembrance Day bombing by Provisional IRA (1987)

• Peace Process begins (1988)

• Operation Flavius, Milltown Cemetery attack and Corporals killings (1988)

• Bishopsgate bombing (1993)

• Downing Street Declaration (1993)

• First Provisional IRA ceasefire (1994)

• Loyalist ceasefire (1994)

• Docklands bombing (1996)

• 1996 Manchester bombing (1996)

• Second Provisional IRA ceasefire (1997)

• Good Friday Agreement (1998) signals the end of the Troubles

• Assembly elections held, with SDLP and UUP winning most seats (1998)

• Omagh bombing by dissident Real IRA (1998)• Unionist parties:

• Democratic Unionist Party

• Northern Ireland Unionist Party

• Ulster Unionist Party

• Progressive Unionist Party

• Conservative Party

• UK Unionist Party

• Traditional Unionist Voice

• Nationalist parties:

• Democratic Left

• Fianna Fáil

• Fine Gael

• Labour Party

• Progressive Democrats

• Sinn Féin

• Social Democratic & Labour Party

• Workers' Party of Ireland

• Irish Republican Socialist Party

• Republican Sinn Féin

• Cross-community parties:

• Alliance Party

• Historically important parties:

• Nationalist Party

• Northern Ireland Labour Party

• Protestant Unionist Party

• Vanguard Unionist Progressive Party

• Northern Ireland Women's Coalition

• People's Democracy

• Republican Labour Party

• Anti H-Block

• Irish Independence Party The Troubles at Wiktionary ·

The Troubles at Wiktionary ·  The Troubles at Wikibooks ·

The Troubles at Wikibooks ·  The Troubles at Wikiquote ·

The Troubles at Wikiquote ·  The Troubles at Wikisource ·

The Troubles at Wikisource ·  The Troubles at Commons ·

The Troubles at Commons ·  The Troubles at WikinewsCategories:

The Troubles at WikinewsCategories:- Conflicts in 1971

- 1971 in Northern Ireland

- Riots and civil disorder in Northern Ireland

- Human rights abuses

- Internments

- The Troubles (Northern Ireland)

- Military operations involving the United Kingdom

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.