- Fear

-

For other uses, see Fear (disambiguation).

A scared child shows fear in an uncertain environment.

A scared child shows fear in an uncertain environment.

Fear is a distressing negative sensation induced by a perceived threat. It is a basic survival mechanism occurring in response to a specific stimulus, such as pain or the threat of danger. In short, fear is the ability to recognize danger leading to an urge to confront it or flee from it (also known as the fight-or-flight response) but in extreme cases of fear (terror) a freeze or paralysis response is possible. Some psychologists such as John B. Watson, Robert Plutchik, and Paul Ekman have suggested that fear belongs to a small set of basic or innate emotions. This set also includes such emotions as joy, sadness, and anger. Fear should be distinguished from the related emotional state of anxiety, which typically occurs without any certain or immediate external threat. Additionally, fear is frequently related to the specific behaviors of escape and avoidance, whereas anxiety is the result of threats which are perceived to be uncontrollable or unavoidable.[1] It is worth noting that fear almost always relates to future events, such as worsening of a situation, or continuation of a situation that is unacceptable. Fear can also be an instant reaction to something presently happening.

Contents

Common fears

According to surveys, some of the most common fears are of ghosts, the existence of evil powers, cockroaches, spiders, snakes, heights, water, enclosed spaces, tunnels, bridges, needles, social rejection, failure, examinations and public speaking. In an innovative test of what people fear the most, Bill Tancer analyzed the most frequent online search queries that involved the phrase, "fear of...". This follows the assumption that people tend to seek information on the issues that concern them the most. His top ten list of fears consisted of flying, heights, clowns, intimacy, death, rejection, people, snakes, success, and driving.[2]

One of the common fear can be the fear of public speaking. People may be expertised speakers inside a room but when it becomes public speaking, fear enters in the form of suspicion that whether the words uttered are correct or wrong because there are many to judge it. Another common fear can be of pain, or of someone damaging a person. Fear of pain in a plausible situation brings flinching, or cringing.

In a 2005 Gallup poll (U.S.A.), a national sample of adolescents between the ages of 13 and 15 were asked what they feared the most. The question was open ended and participants were able to say whatever they wanted. The most frequently cited fear (mentioned by 8% of the teens) was terrorism. The top ten fears were, in order: terrorist attacks, spiders, death, being a failure, war, heights, criminal or gang violence, being alone, the future, and nuclear war.[3]

Causes

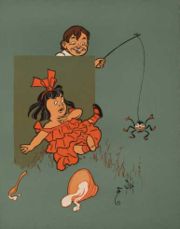

Though most arachnids are harmless, a person with arachnophobia may still panic or feel uneasy around one. Sometimes, even an object resembling a spider can trigger a panic attack in an arachnophobic individual. The above cartoon is a depiction of the nursery rhyme "Little Miss Muffet", in which the title character is "frightened away" by a spider.

Though most arachnids are harmless, a person with arachnophobia may still panic or feel uneasy around one. Sometimes, even an object resembling a spider can trigger a panic attack in an arachnophobic individual. The above cartoon is a depiction of the nursery rhyme "Little Miss Muffet", in which the title character is "frightened away" by a spider.

People develop specific fears as a result of learning. This has been studied in psychology as fear conditioning, beginning with John B. Watson's Little Albert experiment in 1920. In this study, an 11-month-old boy was conditioned to fear a white rat in the laboratory. The fear became generalized to include other white, furry objects. In the real world, fear can be acquired by a frightening traumatic accident. For example, if a child falls into a well and struggles to get out, he or she may develop a fear of wells, heights (acrophobia), enclosed spaces (claustrophobia), or water (aquaphobia). There are studies looking at areas of the brain that are affected in relation to fear. When looking at these areas (amygdala), it was proposed that a person learns to fear regardless of whether they themselves have experienced trauma, or if they have observed the fear in others. In a study completed by Andreas Olsson, Katherine I. Nearing and Elizabeth A. Phelps the amygdala were affected both when subjects observed someone else being submitted to an aversive event, knowing that the same treatment awaited themselves, and when subjects were subsequently placed in a fear-provoking situation. This suggests that fear can develop in both conditions, not just simply from personal history.

The experience of fear is affected by historical and cultural influences. For example, in the early 20th century, many Americans feared polio, a disease that cripples the body part it affects, leaving that body part immobilized for the rest of one's life. There are also consistent cross-cultural differences in how people respond to fear. Display rules affect how likely people are to show the facial expression of fear and other emotions.

Although fear is learned, the capacity to fear is part of human nature. Many studies have found that certain fears (e.g. animals, heights) are much more common than others (e.g. flowers, clouds). These fears are also easier to induce in the laboratory. This phenomenon is known as preparedness. Because early humans that were quick to fear dangerous situations were more likely to survive and reproduce, preparedness is theorized to be a genetic effect that is the result of natural selection.

From an evolutionary psychology perspective, different fears may be different adaptations that have been useful in our evolutionary past. They may have developed during different time periods. Some fears, such as fear of heights, may be common to all mammals and developed during the mesozoic period. Other fears, such as fear of snakes, may be common to all simians and developed during the cenozoic time period. Still others, such as fear of mice and insects, may be unique to humans and developed during the paleolithic and neolithic time periods (when mice and insects become important carriers of infectious diseases and harmful for crops and stored foods).[4]

Neurobiology

The amygdala is a key brain structure in the neurobiology of fear. It is involved in the processing of negative emotions (such as fear and anger). Researchers have observed hyperactivity in the amygdala when patients were shown threatening faces or confronted with frightening situations. Patients with a more severe social phobia showed a correlation with increased response in the amygdala.[5] Studies have also shown that subjects exposed to images of frightened faces, or faces of people from another race,[6] exhibit increased activity in the amygdala.

The fear response generated by the amygdala can be mitigated by another brain region known as the rostral anterior cingulate cortex, located in the frontal lobe. In a 2006 study at Columbia University, researchers observed that test subjects experienced less activity in the amygdala when they consciously perceived fearful stimuli than when they unconsciously perceived fearful stimuli. In the former case, they discovered the rostral anterior cingulate cortex activates to dampen activity in amygdala, granting the subjects a degree of emotional control.[7]

The role of the amygdala in the processing of fear-related stimuli has been questioned by research upon those in which it is bilateral damaged. Even in the absence of their amygdala, they still react rapidly to fearful faces.[8]

Suppression of amygdala activity can also be achieved by pathogens. Rats infected with the toxoplasmosis parasite become less fearful of cats, sometimes even seeking out their urine-marked areas. This behavior often leads to them being eaten by cats. The parasite then reproduces within the body of the cat. There is evidence that the parasite concentrates itself in the amygdala of infected rats.[9]

Several brain structures other than the amygdala have also been observed to be activated when individuals are presented with fearful vs. neutral faces, namely the occipitocerebellar regions including the fusiform gyrus and the inferior parietal / superior temporal gyri.[10] Interestingly, fearful eyes, brows and mouth seem to separately reproduce these brain responses.[10] Scientist from Zurich studies show that the hormone oxytocin related to stress and sex reduces activity in your brain fear center[11] Process of fear -The thalamus collects sensory data from the senses -Sensory cortex receives data from thalamus and interprets it -Sensory cortex organizes information for dissemination to hypothalamus (fight or flight), amygdala (fear), hippocampus (memory)

Fear of death

Psychologists have addressed the hypothesis that fear of death motivates religious commitment, and that it may be alleviated by assurances about an afterlife. Empirical research on this topic has been equivocal.[citation needed] According to Kahoe and Dunn, people who are most firm in their faith and attend religious services weekly are the least afraid of dying. A survey of people in various Christian denominations showed a negative correlation between fear of death and religious concern.[12]

In another study, data from a sample of white, Christian men and women were used to test the hypothesis that traditional, church-centered religiousness and de-institutionalized spiritual seeking are distinct ways of approaching fear of death in old age. Both religiousness and spirituality were related to positive psychosocial functioning, but only church-centered religiousness protected subjects against the fear of death.[13]

Fear of death is also known as death anxiety. This may be a more accurate label because, like other anxieties, the emotional state in question is long lasting and not typically linked to a specific stimulus. The analysis of fear of death, death anxiety, and concerns over mortality is an important feature of existentialism and terror management theory.

Fear of death is also known as Thanatophobia.[14]

See also

- Anxiety

- Anxiety attack

- Anxiety disorder

- Appeal to fear

- Culture of fear

- Fear mongering

- Fight-or-flight response

- Horror and terror

- Hysteria

- Night terror

- Nightmare

- Ontogenetic parade

- Panic

- Panic attack

- Paranoia

- Phobia

- Psychological trauma

- Shock

- Social anxiety disorder

- Social anxiety

References

- ^ Öhman, A. (2000). Fear and anxiety: Evolutionary, cognitive, and clinical perspectives. In M. Lewis & J. M. Haviland-Jones (Eds.). Handbook of emotions. (pp.573–593). New York: The Guilford Press.

- ^ Tancer, B. (2008). Click: What millions of people are doing online and why it matters. New York: Hyperion.

- ^ Gallup Poll: What Frightens America's Youth, March 29, 2005 Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ^ Bracha, H. (2006). "Human brain evolution and the "Neuroevolutionary Time-depth Principle:" Implications for the Reclassification of fear-circuitry-related traits in DSM-V and for studying resilience to warzone-related posttraumatic stress disorder". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry 30 (5): 827–853. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.01.008. PMID 16563589.

- ^ Studying Brain Activity Could Aid Diagnosis Of Social Phobia. Monash University. January 19, 2006.

- ^ Hart AJ, Whalen PJ, Shin LM, McInerney SC, Fischer H, Rauch SL (August 2000). "Differential response in the human amygdala to racial outgroup vs ingroup face stimuli.". Neuroreport 11 (11): 2351–5. doi:10.1097/00001756-200008030-00004. PMID 10943684.

- ^ Emotional Control Circuit Of Brain's Fear Response Discovered. Retrieved on May 14, 2008.

- ^ Tsuchiya N, Moradi F, Felsen C, Yamazaki M, Adolphs R. (2009). "Intact rapid detection of fearful faces in the absence of the amygdala". Nat Neurosci 12 (10): 1224–12225. doi:10.1038/nn.2380. PMC 2756300. PMID 19718036. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=2756300.

- ^ Berdoy M, Webster J, Macdonald D (2000). Fatal Attraction in Rats Infected with Toxoplasma gondii. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, B267:1591–1594. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1182 PMID 11007336

- ^ a b Radua, Joaquim; Phillips, Mary L.; Russell, Tamara; Lawrence, Natalia; Marshall, Nicolette; Kalidindi, Sridevi; El-Hage, Wissam; McDonald, Colm et al. (2010). "Neural response to specific components of fearful faces in healthy and schizophrenic adults". NeuroImage 49 (1): 939–946. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.08.030. PMID 19699306.

- ^ Fear not." Ski Mar.-Apr. 2009: 15. Gale Canada In Context. Web. 29 Sep. 2011

- ^ Kahoe, R. D., & Dunn, R. F. (1976). "The fear of death and religious attitudes and behavior". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 14 (4): 379–382. doi:10.2307/1384409. JSTOR 1384409.

- ^ Wink, P. (2006). "Who is afraid of death? Religiousness, spirituality, and death anxiety in late adulthood". Journal of Religion, Spirituality, & Aging 18 (2): 93–110. doi:10.1300/J496v18n02_08.

- ^ Phobias.about.com

- Hinton, D. E., Lewis-Fernadex, R., and Pollack, M. H.. (2009). A Model of the Generation of Ataque de Nervios: The Role of Fear of Negative Affect and Fear of Arousal Symptoms. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 15(3): 264-275.

- Mears, D. P. and Stewart, E. A.. (2010). Interracial Contact and Fear of Crime. Journal of Criminal Justice. 38(1): 34-41.

- Sanders, M. J., Stevens, S. and Boeh, H.. (2010). Stress Enhancement of Fear Learning in Mice is Dependent Upon Stressor Type: Effects of Sex and Ovarian Hormones. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 94(2): 254-262.

Further reading

- Bourke, Joanna (2005). Fear: a cultural history. Virago. ISBN 1593761139.

- Robin, Corey (2004). Fear: the history of a political idea. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195157028.

- Duenwald, Mary (January 2005). "The Physiology of ... Facial Expressions". Discover 26 (1). http://discovermagazine.com/2005/jan/physiology-of-facial-expressions/?searchterm=duenwald.

- Gardner, Dan (2008). Risk: The Science and Politics of Fear. Random House, Inc. ISBN 0771032994.

- Jiddu, Krishnamurti (1995). On Fear. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-251014-2.

External links

- How Stuff Works – Fear

- The Scent of Fear, a Research Study

- Catholic Encyclopedia "Fear (from a Moral Standpoint)"

- Traversing the realm of Fear

Categories:- Fear

- Emotions

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.