- Gastric acid

-

Gastric acid is a digestive fluid, formed in the stomach. It has a pH of 1 to 2 and is composed of hydrochloric acid (HCl) (around 0.5%, or 5000 parts per million), and large quantities of potassium chloride (KCl) and sodium chloride (NaCl). The acid plays a key role in digestion of proteins, by activating digestive enzymes, and making ingested proteins unravel so that digestive enzymes can break down the long chains of amino acids.

Gastric acid is produced by cells lining the stomach, which are coupled to systems to increase acid production when needed. Other cells in the stomach produce bicarbonate to buffer the acid, ensuring the pH does not drop too low (acid reduces pH). Also cells in the beginning of the small intestine, or duodenum, produce large amounts of bicarbonate to completely neutralize any gastric acid that passes further down into the digestive tract. The bicarbonate-secreting cells in the stomach also produce and secrete mucus. Mucus forms a viscous physical barrier to prevent gastric acid from damaging the stomach.

The presence of gastric acid in the stomach and its function in digestion was first characterized by U.S. Army surgeon William Beaumont around 1830. Beaumont was able to study the stomach action of fur trapper Alexis St. Martin due to the latter's gastric fistula.

Contents

Physiology

Gastric acid is produced by parietal cells (also called oxyntic cells) in the stomach. Its secretion is a complex and relatively energetically expensive process. Parietal cells contain an extensive secretory network (called canaliculi) from which the gastric acid is secreted into the lumen of the stomach. These cells are part of epithelial fundic glands in the gastric mucosa. The pH of gastric acid is 1.35 to 3.5 [1] in the human stomach lumen, the acidity being maintained by the proton pump H+/K+ ATPase. The parietal cell releases bicarbonate into the blood stream in the process, which causes a temporary rise of pH in the blood, known as alkaline tide.

The resulting highly acidic environment in the stomach lumen causes proteins from food to lose their characteristic folded structure (or denature). This exposes the protein's peptide bonds. The chief cells of the stomach secrete enzymes for protein breakdown (inactive pepsinogen and rennin). HCl activates pepsinogen into the enzyme pepsin, which then helps digestion by breaking the bonds linking amino acids, a process known as proteolysis. In addition, many microorganisms have their growth inhibited by such an acidic environment, which is helpful to prevent infection.

Secretion

Gastric acid secretion happens in several steps. Chloride and hydrogen ions are secreted separately from the cytoplasm of parietal cells and mixed in the canaliculi. Gastric acid is then secreted into the lumen of the oxyntic gland and gradually reaches the main stomach lumen. The exact manner in which the secreted acid reaches the stomach lumen is controversial, as acid must first cross the relatively pH neutral gastric mucus layer.

Chloride and sodium ions are secreted actively from the cytoplasm of the parietal cell into the lumen of the canaliculus. This creates a negative potential of -40 mV to -70 mV across the parietal cell membrane that causes potassium ions and a small number of sodium ions to diffuse from the cytoplasm into the parietal cell canaliculi.

The enzyme carbonic anhydrase catalyses the reaction between carbon dioxide and water to form carbonic acid. This acid immediately dissociates into hydrogen and bicarbonate ions. The hydrogen ions leave the cell through H+/K+ ATPase antiporter pumps.

At the same time sodium ions are actively reabsorbed. This means that the majority of secreted K+ and Na+ ions return to the cytoplasm. In the canaliculus, secreted hydrogen and chloride ions mix and are secreted into the lumen of the oxyntic gland.

The highest concentration that gastric acid reaches in the stomach is 160 mM in the canaliculi. This is about 3 million times that of arterial blood, but almost exactly isotonic with other bodily fluids. The lowest pH of the secreted acid is 0.8,[2] but the acid is diluted in the stomach lumen to a pH between 1 and 3.

There are three phases in the secretion of gastric acid:

- The cephalic phase: Thirty percent of the total gastric acid secretions to be produced is stimulated by anticipation of eating and the smell or taste of food.

- The gastric phase: Sixty percent of the acid secreted is stimulated by the distention of the stomach with food. Plus, digestion produces proteins, which causes even more gastrin production.

- The intestinal phase: The remaining 10% of acid is secreted when chyme enters the small intestine, and is stimulated by small intestine distention.

There is also a small continuous basal secretion of gastric acid between meals of usually less than 10 mEq/hour.[3]

Regulation of secretion

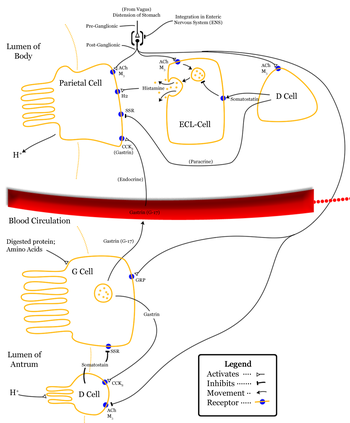

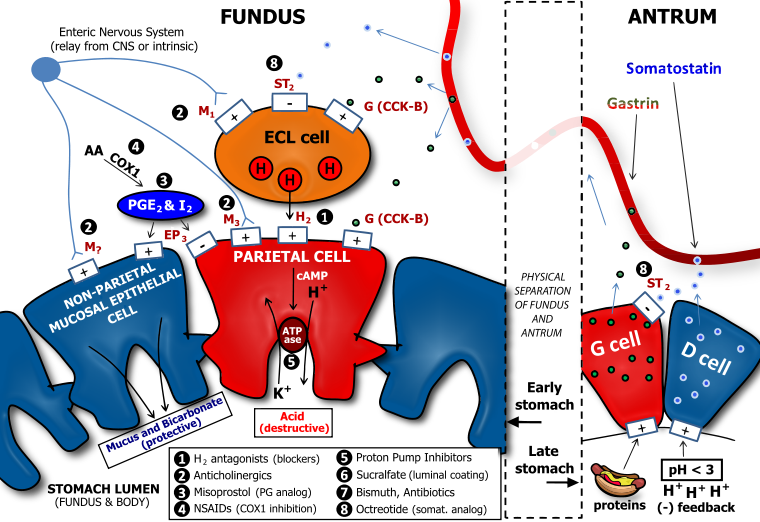

Gastric acid production is regulated by both the autonomic nervous system and several hormones. The parasympathetic nervous system, via the vagus nerve, and the hormone gastrin stimulate the parietal cell to produce gastric acid, both directly acting on parietal cells and indirectly, through the stimulation of the secretion of the hormone histamine from enterochromaffine-like cells (ECL). Vasoactive intestinal peptide, cholecystokinin, and secretin all inhibit production.

The production of gastric acid in the stomach is tightly regulated by positive regulators and negative feedback mechanisms. Four types of cells are involved in this process: parietal cells, G cells, D cells and enterochromaffine-like cells. Besides this, the endings of the vagus nerve (CN X) and the intramural nervous plexus in the digestive tract influence the secretion significantly.

Nerve endings in the stomach secrete two stimulatory neurotransmitters: acetylcholine and gastrin-releasing peptide. Their action is both direct on parietal cells and mediated through the secretion of gastrin from G cells and histamine from enterochromaffine-like cells. Gastrin acts on parietal cells directly and indirectly too, by stimulating the release of histamine.

The release of histamine is the most important positive regulation mechanism of the secretion of gastric acid in the stomach. Its release is stimulated by gastrin and acetylcholine and inhibited by somatostatin.

Neutralization

In the duodenum, gastric acid is neutralized by sodium bicarbonate. This also blocks gastric enzymes that have their optima in the acid range of pH. The secretion of sodium bicarbonate from the pancreas is stimulated by secretin. This polypeptide hormone gets activated and secreted from so-called S cells in the mucosa of the duodenum and jejunum when the pH in duodenum falls below 4.5 to 5.0. The neutralization is described by the equation:

-

- HCl + NaHCO3 → NaCl + H2CO3

The carbonic acid instantly decomposes into carbon dioxide and water.

Role in disease

In hypochlorhydria and achlorhydria, there is low or no gastric acid in the stomach, potentially leading to problems as the disinfectant properties of the gastric lumen are decreased. In such conditions, there is greater risk of infections of the digestive tract (such as infection with Vibrio or Helicobacter bacteria).

In Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and hypercalcemia, there are increased gastrin levels, leading to excess gastric acid production, which can cause gastric ulcers.

In diseases featuring excess vomiting, patients develop hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis (decreased blood acidity by H+ and chlorine depletion).

Pharmacology

The proton pump enzyme is the target of proton pump inhibitors, used to increase gastric pH in diseases that feature excess acid. H2 antagonists indirectly decrease gastric acid production. Antacids neutralize existing acid.

History

The role of gastric acid in digestion was established in the 1820s and 1830s by William Beaumont on Alexis St. Martin, who, as a result of an accident, had a fistula (hole) in his stomach, which allowed Beaumont to observe the process of digestion and to extract gastric acid, verifying that acid played a crucial role in digestion.[4]

See also

- Stomach

- Digestion

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- Discovery and development of proton pump inhibitors

Notes

- ^ Marieb EN, Hoehn K (2010). Human anatomy & physiology. San Francisco: Benjamin Cummings. ISBN 0-8053-9591-1.

- ^ Guyton, Arthur C.; John E. Hall (2006). Textbook of Medical Physiology (11 ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders. p. 797. ISBN 0721602401.

- ^ Page 192 in: Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-7153-6.

- ^ Harré, R. (1981). Great Scientific Experiments. Phaidon (Oxford). pp. 39 – 47. ISBN 0-7148-2096-2.

External links

- The Parietal Cell: Mechanism of Acid Secretion at vivo.colostate.edu

- First Principles of Gastroenterology. Chapter 6. Salena B. J., Hunt R. H. The Stomach and Duodenum

- "Gastric juice" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

Digestive system, physiology: gastrointestinal physiology GI tract Upper GIExocrineProcessesFluidsLower GIEndocrine/paracrineG cells (gastrin) · D cells (somatostatin) · ECL cells (Histamine)

enterogastrone: I cells (CCK) · K cells (GIP) · S cells (secretin)

Enteroendocrine cells · Enterochromaffin cell · APUD cellFluidsProcessesEither/bothProcessesAccessory FluidsProcessesAbdominopelvic Categories:- Acids

- Body fluids

- Digestive system

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.