- Sarakatsani

-

Sarakatsani

(Σαρακατσάνοι)

Karakachani

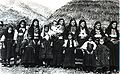

(Каракачани)Sarakatsani children in Kotel, Bulgaria.

Total population unknown Regions with significant populations  Greece

Greece80,000 (1950s estimate) [1]  Bulgaria

Bulgaria2,511 (2011)[2] - 25,000[3][4] [5] Languages Greek, Bulgarian and other languages in the areas in which they live.

Religion Related ethnic groups The Sarakatsani (Greek: Σαρακατσάνοι, Bulgarian: каракачани, karakachani) are a group of Greek[6][7] transhumant shepherds inhabiting chiefly Greece, with a smaller presence in neighbouring Bulgaria, southern Albania and the Republic of Macedonia. Historically centered around the Pindus mountains, they have been currently urbanised to a significant degree. Most of them now reside throughout Central and Northern Greece[8] and are of Greek Orthodox faith.[9]

Contents

History and origin

Despite the silence of the classical and medieval writers, most scholars argue that the Sarakatsani have ancient origins, descended from pre-classical indigenous pastoralists, citing linguistic evidence and certain aspects of their traditional culture and socioeconomic organization. The anthropological characteristics of the Sarakatsani also classify them as one of the earliest populations on the Balkans and Europe. Their origins have been the subject of broad and permanent interest.

19th-century accounts

Many of the 19th century descriptions of the Sarakatsani do not differentiate between them and the other great shepherd tribe of Greece, the Vlachs, who are of Latin origin. In many instances the Sarakatsani were simplifyingly described as Vlachs. In his Monograph on Koutsovlachs (Μονογραφία περι Κουτσόβλαχων, 1865, reprinted in 1905), an Epirote Greek named Aravantinos discussed how the Arvanitovlachs were erroneously called Sarakatsani although the latter were of clearly Greek origin.[10]

In another work of the same author titled Chronography (Χρονογραφία), he elaborates more on the Sarakatsani and discusses the existence of the Sarakatsani. He also states that the Arvanitovlachs were called Garagounides or Korakounides, increasing the differences between Arvanitovlachs and Sarakatsani, who, according to one theory, originated in the Greek village of Saraketsi.[11] According to the Aromanian scholar Theodor Capidan, the Sarakatsani (sărăcăciani) originate from the Aromanian village of Syrrako situated S-E of Ioanina in Epirus.

There were other names the Sarakatsani were referred to such as Roumeliotes (by authors such as Georges Kavadias), even though the Sarakatsani did not use that name themselves, or Moraites (according to Fotakos) when they migrated to Thessaly from Morea after 1881.

Otto, the first king of modern Greece, was well-known to be a great admirer of the Sarakatsani, and is said to have early in his reign fathered an illegitimate child with a woman from a Sarakatsani clan named "Tangas".[12] This child, named Manoli Tangas, was brought to Athens and remained there after Otto's 1862 departure, living as a merchant trader with children of his own. The descendants of Manoli still reside in Athens today.[13]

20th-century accounts

A multitude of 20th century scholars have studied the linguistic, cultural, and racial background of the Sarakatsani. By now, they have clearly distinguished the Sarakatsani as a distinct entity, and the linguistic, cultural, and racial background of the Sarakatsani have started to be meticulously researched.

Among these, the Danish scholar Carsten Høeg, who traveled twice to Greece between 1920 and 1925, is arguably the most influential. He visited the Sarakatsani in Epirus and began studying their dialect and narrations. Høeg published his findings in 1926 in his book entitled The Sarakatsani.

In his work, he stated that there are no significant traces of foreign loan words in the Sarakatsani dialect, such foreign linguistic elements being found neither phonetically nor are in the overall grammatical structure of the dialect. (These conclusions, however, were disputed by later researchers who did locate loan words in the Sarakatsani dialect). In addition to this, Høeg writes that the Sarakatsani material culture shows the trace of sedentary origins.

There were groups of Sarakatsani in the 20th century with no fixed villages, whether in summer time or in winter, traced as such by Høeg. He also found the Sarakatsani in several parts of Greece, Thessaly, Macedonia, Pelagonia, Thrace, around Lake Copais in Boeotia, and on mountain ranges like Pindus, Rhodope and Vermion.

Høeg attempted to find examples of nomadism in Classical Greece as an equation for that of the Sarakatsani. Høeg was criticized by Georges Kavadias for exaggerating the link between the 20th century Sarakatsani population and the ancient Greeks. Ultimately, Høeg's background of Classical Greek scholarship was thought as having influenced - sometimes in a biased way - the conclusions he outlined as to the origins of Sarakatsani.

A German scholar, Beuermann, rejects Høeg's rationalizations of these facts, which is relevant to the claim frequently put forward that the Sarakatsani are the "purest of the Ancient Greek population". There appears to be no written mention of the Sarakatsani previous to the 18th century. That does not neccesarily imply that bthey did not exist earlier - one can also conclude that the term Sarakatsani is a relatively new generic name given to a quite an old population that lived for centuries in isolation from the other inhabitants of what is today Greece.

Georgakas (1949) and Kavadias (1965) believe that either the Sarakatsani are descendants of ancient nomads who inhabited the mountain regions of Greece in the pre-Classical times, or they are descended from sedentary Greek peasants forced to leave their original settlements around the 14th century and to become nomadic shepherds.

Angeliki Chatzimichali, a Greek ethnographer who spent a lifetime among them and published her work in 1957, remarks the prototypical elements of Greek culture that can be found throughout the pastoral way of life, social organization, and art of the Sarakatsani, pointing to the similarity between the Sarakatsan decorative art and the geometric art of pre-classical Greece.[14]

In 1964 the English researcher J.K. Campbell arrived at the conclusion that Sarakatsani must always have lived in more or less the same conditions and areas as they were found in his day - they were very endogamic and they should be considered an isolate group. E. Makris (1990) believes that they are a pre-Neolithic people.

Nicholas Hammond, a British historian, after his treatment concentrated on the Sarakatsani populations of Epirus, in his work Migrations and Invasions in Greece and Adjacent Areas (1976), considers them descendants of Greek pastoralists who herded their sheep on the central range of Gramos and Pindus in the early Byzantine period and were dispossessed of their pastures by the Vlachs at the latest by the 12th century.[15]

In 1987 the London-based scholar John Nandris, who observed the Sarakatsani "on the ground" continuously since the 1950s, summarized his account of this tribe by inserting them in a more complex context of nomadic people interacting with one another. He alludes to the Yörük connection though he is keen not to jump to any definitive conclusion. This theory was also supported by Arnold van Gennep.

Sarakatsani and Vlachs

During the 20th century and up to the present day, Romanian and Aromanian scholars have tried to prove the supposed common origin of the Sarakatsani and the Aromanians; the latter are speakers of a Romance language and the other major transhumant tribe in Greece. The Aromanians speak Aromanian, an eastern Romance language, while the Sarakatsani speak a clearly northern dialect of Greek.

The Sarakatsani Greek dialect does, however, include a few base vocabulary Vlach words. A recent study focuses on Aromanian elements in Sarakatsan Greek states that most Aromanian influences in Sarakatsan Greek are not old borrowing but were incorporated into Greek as a result of recent contacts and economical dependencies of the groups.[16]

The Sarakatsani partially share the geographic distribution of Vlachs in Greece although they extend farther to the south. However the presumption that a nomadic society such as the Sarkatsani would abandon its language, then translate all of its verbal tradition into Greek and create within a few generations a separate Greek dialect, has to be examined with caution.

Despite the differences between the Sarakatsani and the Aromanians, Sarakatsani themselves often use the ethnonym Vlach (Greek: Βλάχοι) in their Greek dialect.[citation needed] However, the term "Vlach" in Greece has been used since Byzantine times to indiscriminately refer to all transhumant pastoralists, irrespective of ethnic background.[17]

John Campbell, social anthropologist, states, after his own field work among the Sarakatsani in the 1950s, that the Sarakatsani are in a different position from the Vlachs, meaning the Aromanians and the Arvanitovlachs, who both speak an eastern Romance language along with Greek, while the Sarakatsani communities were always Greek-speaking and knew no other language.

Campbell also asserts that the increasing pressure on the limited areas available for winter grazing in the coastal plains had resulted in a competitive dispute between the two groups on the use of the pastures. In addition, during the time of his research Vlach groups often lived in substantial villages where shepherding was not among their occupations, while their cultural elements such as art forms, values and institutions, are different from those of the Sarakatsani.[17] The latter, for instance, differ from the Vlachs in that they dower their daughters, assign a lower position to women and adhere to even stricter patriarchal structure.[15]

The Sarakatsani themselves have always stressed their Greek identity and deny having any relationship with the Vlachs. The Vlachs also regard the Sarakatsani as a distinct ethnic group, calling them Graikoi (i.e. Greeks), a name used by Aromanians to distinguish the Greek-speaking populations from themselves, the Armâni/Rămăni.

Name

The most popular theory about the origin of the name Sarakatsani or Karakatsani, is that it probably derives from the Turkish word karakaçan (kara = 'black' + kaçan = 'fugitive') meaning 'those who flee to uncultivated lands'.[18] As noted above, the Aromanian scholar Theodor Capidan proposed the theory that the name is derived from the Aromanian village of Syrrako situated S-E of Ioanina in Epirus.

Culture

Part of a series on Greeks

By region or country Greece · Cyprus

Greek diasporaSubgroups Antiochians · Arvanites/Souliotes

Cypriots · Grecanici

Karamanlides · Macedonians

Maniots · Northern Epirotes

Phanariotes · Pontians

Romaniotes · Sarakatsani

Sfakians · Slavophones

Tsakonians · UrumsGreek culture Art · Cinema · Cuisine

Dance · Dress · Education

Flag · Language · Literature

Music · Philosophy · Politics

Religion · Sport · TelevisionReligion Greek Orthodox Church

Greek Roman Catholicism

Greek Byzantine Catholicism

Greek Evangelicalism

Judaism · Islam · NeopaganismLanguages and dialects Greek

Calabrian Greek

Cappadocian Greek

Cretan Greek · Griko

Cypriot Greek

Cheimarriotika · Maniot Greek

Pontic Greek · Tsakonian

Yevanic · Arvanitika

Karamanlidika · Slavika

UrumHistory of Greece The Sarakatsani speak a northern Greek dialect,[19] Sarakatsanika, which contains many archaic Greek elements that have not survived in other variants of modern Greek,[20] and loanwords from neighboring non-Greek languages.[19]

Almost all Sarakatsani in Greece have abandoned their nomadic way of life and assimilated to mainstream modern Greek life. According to John Campbell, their settlements, dress and costumes make them a distinct social and cultural group as part of the collective Greek heritage, but they do not constitute an ethnic minority.[17]

Their folk art consists of song, dance, poetry, and some decorative sculpture in wood, as well as elaborate embroidery such as that which adorns their traditional costume. Principal motives used in sculpture and embroidery are geometrical shapes and human and plant representations.

As far as their medicine is concerned, the Sarakatsani use a number of folk remedies that make use of herbs, honey, lamb's blood or a combination thereof.

Kinship

Among the Sarakatsani there is a strong patrilineal bias, and when reckoning descent — as opposed to determining contemporary family relationships — lineage membership is calculated along the paternal line alone. Contemporary kin relationships are not counted beyond the degree of the second cousin.

Within the kindred, the family constitutes the significant unit and is, unlike the larger network of personal relations of the kindred, a corporate group. The descendants of a man's maternal and paternal grandparents provide the field from which his recognized kin are drawn.

The extended family has at its core a conjugal pair, and includes their unmarried offspring, and, often, their young married sons and their wives. The Sarakatsani kindred constitutes a network of shared obligations and, to a degree, cooperation in situations concerning the honor of its members.

Sarakatsani marriages are arranged, with the initiative in such arrangements taken by the family of the prospective husband in consultation with members of the kindred. There can be no marriage between two members of the same kindred.

The bride must bring with her into the marriage a dowry of household furnishings, clothing, and, more recently, sheep or their cash equivalent. The husband's contribution to the wealth of the new household is his share in the flocks held by his father, but these remain held in common by his paternal joint household until some years after his marriage.

The newly established couple initially takes up residence near the husband's family of origin. Divorce is unknown and remarriage after widowhood is unthinkable.

Honor of the kindred

The concept of honor is of great importance to the Sarakatsani. The behavior of any member of a family reflects back upon all its members, therefore the avoidance of negative public opinion, particularly as expressed in gossip, provides a strong incentive to live up to the values and standards of propriety held by the community as a whole.

Men have as their duty the protection of the family's honor, and are therefore watchful of the behavior of the rest of the household. In the wider field of village and national interests, the Sarakatsani are subject to local statutes and Greek law.

Religion

The Sarakatsani are Greek Orthodox Christians and associated with the Church of Greece. Despite the fact that their participation in the institutional forms of the church is not particularly marked, they believe strongly in the concepts of God the Father, Jesus Christ and the Virgin Mary.

God is seen in strongly paternalistic terms, as protector and provider, as judge and as punisher of evil deeds. They have interwoven Christian with folk beliefs like the evil eye. Each hut shelters an icon or icons upon which family devotions focused.

The Sarakatsani honor the feast days of Saint George and Saint Demetrius, which fall just before the seasonal migrations in spring and early winter, respectively.

Especially for the Saint George's feast day, a family kills a lamb in the saint's honor, a ritual that also marks Christmas and the Resurrection of Christ. Easter week is the most important ritual period in Sarakatsani religious life.

Other ceremonial events, outside the formal Christian calendar, are weddings and funerals. Funerals are ritual occasions that involve not only the immediate family of the deceased but also the members of the larger kindred. Funerary practice is consistent with that of the church. Mourning is most marked among the women, and most of all by the widow. Beliefs in the afterlife are conditioned by the teachings of the church, though flavored to some degree by traditions deriving from pre-Christian folk religion.

The family is thought to be a reflection of the relationship expressed among God the Father, the Virgin Mary and Christ, where the father is the family head, responsible for the spiritual life of the family. Each household constitutes an autonomous religious community. Superstitious beliefs and practices, such as the casting of the evil eye, have traditionally been prevalent among the Sarakatsani, however there are no formally recognised magical specialists among them.

Pastoralism

The Sarakatsani traditionally spent the summer months on the mountains and returned to the lower plains in the winter. The migration would start on the eve of Saint George's Day in April and the return migration would start on Saint Demetrius' Day, on October 26. However, according to a theory, the Sarakatsani were not always nomads but only turned to harsh nomadic mountain life to escape Ottoman rule.[21][22] Yet many of the Sarakatsani residing in Epirus, Macedonia and Thrace, provinces that remained under Ottoman control until 1913, developed subsequently amiable relationships with the Turkish officials who were among the purchasers of their dairy products as well as of lamb and mutton.

As national states appeared in the former domain of the Ottoman Empire, new state borders came to separate the summer and winter habitats of many of the Sarakatsani groups. However, until the middle of the 20th century the crossing of borders between Greece, Albania, Bulgaria and Yugoslavia was relatively unobstructed. In the summer, some groups went as far north as the Balkan mountains while the winter they would spend in the warmer plains in vicinity of the Aegean Sea. After 1947, as inter-state borders were sealed with the beginning of the Cold War, some Sarakatsani were not able to migrate anymore and were subsequently settled down outside Greece.

Traditional Sarakatsani settlements were located on or near grazing lands both during summers and winters. The most characteristic type of dwelling was that with a domed hut, framed of branches and covered with thatch. A second type was a wood-beamed, thatched, rectangular structure. In both types, the centerpiece of the dwelling was a stone hearth. The floors and walls were plastered with mud and mule dung. Since the late 1930s, national requirements for the registration of citizens has led many if not most Sarakatsani to adopt as legal residence the villages associated with summer grazing lands, and many Sarakatsani have since built houses in such villages.

During the winter, however, their settlement patterns still follow the more traditional configuration: a group of cooperating households, generally linked by ties of kinship or marriage, build their houses in a cluster on flat land close to the pasturage, with supporting structures (for the cheese merchant and cheese maker) nearby. Pens for goats and folds for newborn lambs and nursing ewes are built close to the settlement. This complex is called stani (στάνη), a term also used to refer to the cooperative group sharing the leased land.

Their life centers year-round on the needs of their flocks. Men and boys are usually responsible for the protection and general care of the flocks, like shearing and milking, while the women occupy with the building of the dwellings, sheepfolds and goat pens, child care, the domestic tasks, preparing, spinning and dying the shorn wool, and additionally they try to keep chickens, the eggs of which provide them with their only personal source of income. Women also keep household vegetable gardens, with some wild herbs used to supplement the family diet. When children are very young, child care is the province of the mother. When boys are old enough to help with the flocks, they accompany their fathers and are taught the skills they will someday need. Similarly, girls learn through observing and assisting their mothers.

The pasturage used by a stani is leased, with the head of each participating family paying a share at the end of each season to tselingas, the stani leader, in whose name the lease was originally taken. Inheritance of an individual's property and wealth at the time of his death is largely passed through males: sons inherit a share of the flocks and property owned by their fathers and mothers. However, household goods may pass to daughters, and prestige of the family is visited on all surviving offspring, regardless of gender.

Demographics

Until the mid-20th century, the Sarakatsani were scattered in many parts of the Balkan Peninsula, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey, Yugoslavia, but today they live mainly in Greece, with only some populations left in Bulgaria. It is difficult to establish the exact number of the Sarakatsani over the years, since they were dispersed and migrated in summer and winter, while they were not considered a discreet group in order that census data specify figures for them. Besides, they are often confused with other population groups, especially with the Vlachs, who are also nomadic shepherds. However, in the mid-1950s their number was estimated to be approximately 80,000 throughout Greece, when the process of urbanization had already started for large masses of Greeks.[23]

In Greece, the Sarakatsani populations can be primarily found in Central Greece on the mountain ranges of Giona, Parnassus and Panaitoliko, in Epirus on Pindus mountains, on Rhodope in Thrace, in Central Euboea, on the mountains Olympus and Ossa, and in other parts of Thessaly and Macedonia. The great percentage of them have abandoned the nomadic way of life and live in their villages, while their descendants have largely populated the principal Greek cities.

Bulgaria

In Bulgaria, according to the 2001 census, 4,107 individuals identified as Sarakatsani (Bulgarian: каракачани, karakachani).[24] In the census, this identification is considered separate from the identity of the Greeks in Bulgaria.[24] Local organizations, however, estimate the number of Sarakatsani at up to 20,000.[25] An alternative Bulgarian theory claims that the Sarakatsani are descendants of Hellenized Thracians who, because of their isolation in the mountains, were not Slavicised.[26] A 2006 Bulgarian government publication regards them as a distinct group of possible Vlach or Slavic origin, which later adopted the Greek language.[24] Most live in the vicinity of Sliven where their headquarters are located, but also along the Stara Planina range.

Contrary to these views, the Sarakatsani self-identify as Greeks because Greek is their mother tongue and they consider themselves "the purest of Greeks". Finally, they add that they are Bulgarian Karakachans because they live in Bulgaria where they, their children and, in quite a few cases, their ancestors were born.[27] The Federation of the Cultural and Educational Associations of Karakachans in Bulgaria maintains that the Karakachans are descended from sedentary Greeks, forced to switch to a nomadic lifestyle around the 14th century.[28]

Rootlesness and ritualization

In her book An Island Apart, the travel writer Sarah Wheeler traces scions of the Sarakatsani in Euboea. They can also be found in the island of Poros. She writes:

“ I was fascinated by this elusive, aloof transhumant tribe with beguilingly mysterious origin. They fanned out all over the Balkans and have most closely associated with the Pindus and the Rodopi mountains in the northern mainland: in the fifties there were about 80.000 of them. They spent half of the year in their mountain pastures and the other half in their lowlands. Their rootlesness was balanced by an elaborate ritualization of almost every aspect of their lives, from costume to the moral code. Evia was the only island used by the Sarakatsani except Poros which was the furthest south they ever got (and perhaps Aegina too). In Evia they were, until this century, only found in the chunk of the island from the Chalcis-Kymi axis northwards about as far an Ayianna, and the cluster of villages around Skiloyanni constituted the most heavily settled Sarakatsani region on the island. There were 50 Sarakatsani families living on Mount Kandili, working as resin-gatherers encased in layers of elaborate costume. Photographs taken only few decades ago of Sarakatsani women in traditional costume sitting outside their wigwam-shaped branch woven huts. Many of them had quite an un-Greek looks, and were fair; perhaps that explains the blond heads you see now. The Sarkatsanoi were known by various names by the indigenous population, usually based on where they were perceived to have come from, and in Evia they were generally called Roumi, Romi or Roumeliotes after the Roumeli region. People often spoke of them misleadingly as Vlachs. They are settled now, mainly as farmers, with their own permanent pasture land. Their story is one of total assimilation. ” Notable Sarakatsani

- Military figures

- Antonis Katsantonis (1775–1809), famous klepht leader in the pre-revolutionary period.

- Kostas Lepeniotis, Antonis Katsantonis' brother, also a klepht.

- Georgios Karaiskakis, famous klepht of the Greek War of Independence

- Anastasios Karatasos, famous klepht of the Greek War of Independence

- Dimitrios Karatasos, famous klepht of the Greek War of Independence

- Elected officials

- Alexandros Karathodoros, (1908–1981), member of parliament (1946–1967), Minister for Transport and Communications (1952–1954)

- Lefteris Zagoritis, Member of Parliament since 2004, Secretary of the New Democracy party.

- Georgios Souflias, Member of Parliament 1974-2000 and 2004–2009, minister in various cabinets since 1977.

- Georgios Sourlas, Member of Parliament 1981-2000 and since 2004, formerly Minister for Health, currently Vice-President of the Parliament.

- Nikolaos Katsaros - Member of Parliament 1981-2004, formerly Vice-President of the Parliament (1989–2000), author of the book «Αρχαιοελληνικές ρίζες του Σαρακατσιάνικου λόγου» ("Ancient Greek roots of the speech of the Sarakatsani").

- Ioannis Printzos, Prefect of Magnisia 2002-2006.

- Loukas Katsaros, Prefect of Larisa since 2002, formerly appointed Prefect of Kozani.

Gallery

-

Sarakatsani children in fustanella.

-

Sarakatsani woman wearing traditional clothing; Pindos, Greece.

References

- ^ "6. Who Plays/Makes the Kaval?". UMBC. http://www.umbc.edu/eol/4/tammer/tammer6.html. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ^ Bulgarian 2011 census; Population by ethnic group

- ^ "Каракачаните.". www.bnr.bg. http://www.bnr.bg/print.htm?id={F24B3D4C-858A-4B55-91A0-438453E8F8B4}&lng=bg. Retrieved 2009-07-16. "translated: Karakachani are one of the smallest ethnic groups in Bulgaria. According to the Federation of culturally-enlightened companies karakachani in Bulgaria, they number around 25,000 people. Most live in the community yuzhnobalgarskiya city Sliven. More significant groups have bases in the villages in Stara Planina, Rila, Pirin and Rhodopes. (original) Каракачаните са един от най-малките етноси в България. По данни от Федерацията на културно-просветите дружества на каракачаните в България те наброяват около 25000 души. Най-голяма общност живее в южнобългарския град град Сливен. По-значителни групи има и в селища по подножията на Стара планина, Рила, Пирин и Родопите"[dead link]

- ^ "Karakachani.". http://news.ibox.bg. http://news.ibox.bg/news/id_1628129467. Retrieved 2009-07-16. "In Bulgaria the community of Karakachani are about 25,000 people, only about 6,000 live in sliven region. (original) България общността на каракачаните е от около 25 000 души , като само 6 000 живеят в Сливенска област"

- ^ "Etnicheski maltsinstveni obshtnosti" (in Bulgarian). Natsionalen savet za satrudnichestvo po etnicheskite i demografskite vaprosi. http://www.nccedi.government.bg/save_pdf.php?id=247. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- ^ Ethnic groups worldwide: a ready reference handbook By David Levinson page 41 :” Sarakatsani are Greek-speaking people in northwestern Greece and southern Bulgaria. They number less than 100 thousand , are ethnically Greek, speak Greek, and are Greek orthodox.”

- ^ .K Campbel Honour, Family and Patronage: A Study of Institutions and Moral Values in a Greek Mountain Community page 3 till page 6: “ In these debates the Greeks and their supporters present the more convincing argument......As is proper for a social anthropologist not concerned with the problem of origins, my own more limited conclusion is that in their social values and institutions, the Sarakatsani as they exist today provide no evidence of a past history that was ever anything but Greek.”

- ^ John Campbell, "The Sarakatsani and the Klephtic Tradition" in Richard Clogg's Minorities in Greece: Aspects of a Plural Society.

- ^ P. Horden, N. Purcell. The corrupting sea: A study of Mediterranean history. Wiley-Blackwell, 2000. p. 493 [1]

- ^ Aravantinos, Μονογραφία περι Κουτσόβλαχων. "Τοιούτους Αρβανιτόβλαχους φερεωίκους ποιμενόβιους ολίγιστους απαντώμεν εν Θεσσαλία και Μακεδονία, Σαρακατσάνους καλουμένους καταχρηστίκους διότι οι Σαρακατσάνοι ορμόνται εξελλήνων και αυτόχρημα Έλληνες εισί."

- ^ Aravantinos. Χρονογραφία. "Σαρακατσιάνοι ή Σακαρετσάνοι έχοντες την καταγωγή εκ Σαρακέτσιου ... Οι Σαρακατσάνοι, οι Πεστανιάνοι, και οι Βλάχοι οι εκ του Σύρρακου εκπατρίσθεντες, οιτίνες και ολιγότερων των άλλων σκηνιτών βαρβαριζούσι. Διάφοροι δε των τριών είσιν οι Αρβανιτόβλαχοι λεγόμενοι Γκαραγκούνιδες ή Κορακούνιδες."

- ^ Poulianos,, Aris Ν. (1993). SARAKATSANI - THE MOST ANCIENT PEOPLE OF EUROPE.

- ^ {"Revival of Sarakatsani Caravan at the 22nd Panhellenic Sarakatsani Conference Thessaloniki, 28.03.2011" by Demetris Tangas, the Secretary of the Sarakatsani Brotherhood in Athens

- ^ Clogg 2002, p. 167

- ^ a b "American Journal of Philology". JSTOR. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0002-9475%28197822%2999%3A2%3C263%3AMAIIGA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-1&size=LARGE&origin=JSTOR-enlargePage. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ "Aromanian elements in Sarakatsan Greek" by Thede Kahl (Austrian Academy of Sciences, Balkan Commission)

- ^ a b c Clogg 2002, p. 166

- ^ Γεώργιος Δ. Μπαμπινιώτης (Babiniotis), Λεξικό της νέας Ελληνικής Γλώσσας Dictionary of the Modern Greek Language, Athens, 1998.

- ^ a b Σαρακατσάνικα στη Bουλγαρία

- ^ Νικόλαος Κατσαρός. Οι αρχαιοελληνικές ρίζες του Σαρακατσάνικου λόγου. Ετυμολογική προσέγγιση, Ι. Σιδέρης, Αθήνα 1995.

- ^ «Σαρακατσάνοι οι σταυραετοί της Πίνδου» ("Sarakatsani, the booted eagles of Pindos") - Vasilis Tsaousis, President of the Folklore Museum of the Sarakatsani.(Greek)

- ^ Hellenic Times, 18 January 2007.(Greek)

- ^ Clogg 2002, p. 165

- ^ a b c "Etnicheski maltsinstveni obshtnosti" (in Bulgarian). Natsionalen savet za satrudnichestvo po etnicheskite i demografskite vaprosi. http://www.nccedi.government.bg/save_pdf.php?id=247. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- ^ Balezdrov, Petar (1997-09-10) (in Bulgarian). Interview with Tanya Varbanova. Makedoniya Newspaper.

- ^ Karakachanite v Balgariya, Zh. Pimpireva, 1995, Bulgarian language, p. 20

- ^ "Karakachans in Bulgaria" (PDF). imir-bg.org. http://www.imir-bg.org/imir/books/karakachans.pdf. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ Karakachani

Bibliograpgy

- Campbell, John K. (1964). Honour, Family, and Patronage: A Study of Institutions and Moral Values in a Greek Mountain Community. Clarendon Press, Oxford. ISBN 1417915595.

- Clogg, Richard (2002). Minorities in Greece: Aspects of a Plural Society. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. pp. 165–178. ISBN 1850657068. http://books.google.com/books?id=231XALxmFFsC&dq.

- Kabbadias, Georgios B. (1965). Nomadic Shepherds of the Mediterranean: The Sarakatsani of Greece. Gauthier-Villars, Paris.

External links

- World Culture Encyclopedia

- Sarakatsani Folklore Museum (Greek)

- The Sarakatsan of Epirus in Athens (Greek)

- The Sarakatsan Organization of Evros Prefecture (Greek)

- The Sarakatsan Association of Drama Prefecture (Greek)

- "Greek Folk Dance Regions: Sarakatsani". Folk with Dunav. Archived from the original on May 24, 2008. http://web.archive.org/web/20080524210727/http://www.dunav.org.il/dance_regions/greece_sarakatsani.html. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

- "Sarakatsani - The Most Ancient People of Europe". Anthropological Association of Greece. http://www.aee.gr/english/5sarakatsani/sarakatsani.html. Retrieved October 28, 2008.

Categories:- Greek people

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- Ethnic groups in Bulgaria

- Ethnic groups in Greece

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.