- Dacian bracelets

-

The Dacian bracelets are bracelets associated with the ancient peoples known as the Dacians, a particularly individualized branch of the Thracians. These bracelets were used as ornaments, currency, high rank insignia and votive offerings[5] Their ornamentations consist of many elaborate regionally distinct styles.[6] Bracelets of various types were worn by Dacians, but the most characteristic piece of their jewelry was the large multi-spiral bracelets; engraved with palmettes towards the ends and terminating in the shape of an animal head, usually that of a snake.[7]

Dacians background

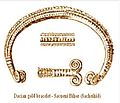

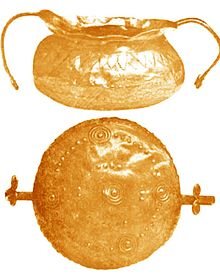

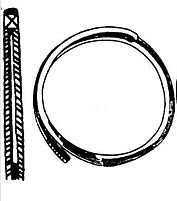

Spiral motif with gold bracelet found in Romania (dated to Bronze IV = Hallstatt A)[8]) repository Kunsthistorisches Museum[9] Horn motif with gold bracelet from Pipea (Mureș County) dated to Hallstatt period [10] or to Bronze Age [11]

Horn motif with gold bracelet from Pipea (Mureș County) dated to Hallstatt period [10] or to Bronze Age [11]

The Dacians lived in a very large territory, stretching from the Balkans to the northern Carpathians and from the Black Sea and the Tyras River (Dniester) to the Tisa plain, and at times as far as the Middle Danube.[12]

Dacian civilization went through several stages of development, from the Thracian stage in the Bronze Age to the Geto-Dacian stage in the classical period that lasted from the 1st century BC to the 1st century AD.[13] The Thracian stage is associated with the emergence of Thracian populations from the fusion of the local Chalcolithic stock with the incoming peoples of the transitional Indo-Europeanization Period.[14][15] By the time of Bronze Age, and during the transitional period to the Iron Age, the cultures of this Carpathian area may be attributed to proto-Thracian and even Thracian populations—ancestors of the peoples known to Herodotus as the Agathyrsae and the Getae, and to the Romans as the Dacians (by Iron Age II).[16][17] The culture of these nuclear groups were typified by military aristocracies.[18]

In these early times the most specific motifs of the bracelets are the spiral and the horn, used to provide the warrior with both physical and deistic protection.[19]

- The spiral motif (i.e. bracelets from Sacosu Mare, Firighiaz (now Firiteaz), Săcueni) is associated with solar cults.[20][9] It might have been an inheritance of the local Chalcolithic culture,[19] or an accentuated Mycenian influence to the north of the Danube.[21]

- The horn motifs (i.e. bracelets from Pipea, Biia (Şona), Boarta (Şeica Mare)) might have been brought by the intrusive stockbreeders (Proto-Indo-Europeans).[19]

The 5th century BC is associated with the Dacian stage of art[22][23] and it is the time of the La Tène period (Iron Age II) when Dacian culture flourished, especially in Transylvanian citadels.[24] The Dacian art of Iron Age II has all the characteristics of a mixed style, with its roots in the Hallstatt culture (1200–500 BC).[25][24] It is characterized by an accentuated geometry, a curvilinear style and plant-based motifs.[6] At this time, besides their older local types, Dacians made all kind of bracelets that were common in the Roman Empire.[26] But, there was a constant preference of Dacians for decorating the silver spiral bracelets with animals protome such as snakes and wolves.[27]

The period of time between the 2nd century BC and 1st century AD is termed "Classic Dacian".[28] At this time the Dacians developed the art of silverworking, and a style which may be described specifically as the Dacian style. It consists of older traditional local elements, dating back to Iron Age I, but also of elements of Celtic, Scythian, Thracian, and especially Greek origins.[29][25] The bracelets of this art-form include silver arm rings, with ends in the shape of stylized heads of animals, and heavy spiral-shaped armlets with gilded ends adorned with palm-leaves, and ending in animal-heads.[29]

The Classic Dacian period ends when parts of the Dacian State were reduced to a Roman province by the Roman Empire under Trajan, partly in order to seize its gold mines. After the Second Dacian War (105–106 AD) Romans claimed they had looted 165,000 kilograms (363,762 pounds) of gold and 300,000 kilograms (661,386 pounds) of silver in a single haul, as estimated by modern historians. This amount seems credible in terms of the Dacian exploitation of precious metals in the Apuseni Mountains along with trade payments and tributes from abroad. Its existence in only one spot (at Sarmizegethusa), suggests that there was a central control of precious metal circulation.[30] According to the majority of historians this sort of monopoly of precious metals, and the Roman's forcible collection of Dacian gold objects, explains the scarcity of archaeological discoveries consisting of golden ornaments for the period between the 3rd century BC – 1st century AD;[31][32] however, the existence of the "Treasures of Dacian kings" has been confirmed by the latest archaeological finds of large gold spiral-shaped bracelets from Sarmizegetusa. It seems that the Romans did not find the entire royal treasure.[33][34]

Bracelets in the transition period North Thracian and proto-Dacian

Types of bracelets in the Bronze Age and First Iron Age

Numerous bracelets were made of bronze and gold and many of them have been found in Transylvania, near the sources of the ores used in their manufacture.[35] They include the following types:

- unequally spiraled armlet made of bronze, worn on the forearm that is also called “arm guard” i.e. those found at Apa (Satu Mare County)[36]

- equally spiraled bracelet, used frequently in the early Hallstatt i.e. Pecica.[36]

- open bracelet with widened ends, made of double gold wire i.e. Ostrovu Mare (Gogoşu).[36]

- bracelet with spiralled or volutes endings i.e. Firighiaz/Firiteaz,[36] Sacoșu Mare.[37]

- open bracelet decorated with incisions, with each end coiled in double opposed volutes i.e. Sacoșu Mare and Hodiş (Bihor County).[36]

- overlapped ends, rhombic cross section i.e. Sacoșu Mare and Şmig.[36] The treasures from Şmig Sibiu County and from Ţufalău (Boroşneu Mare) contained also raw gold, thus suggesting the bracelets had been locally made.[38]

Some bronze bracelet types of the Bronze Age (i.e. incised solid bracelets) continue throughout all the Late Bronze Age and Hallstatt phases.[39]

-

Bronze bracelet dated to Bronze Age - found at Gusterita [40]

-

12th c. BC (Hallstatt A1) Bronze Age bracelets from Gusterita Sibiu County[39]

-

Spiral Bronze Age Dacia found at Gusterita [40]

Various bracelets

Archaeological finds include two gold cylindrical muffs, a characteristic type of the middle and late Bronze Age and widespread throughout Central Europe. Two bronze specimens, both similar to the gold ones, have been discovered at Cehăluţ.[43] The open cuff found at Hinova, and dated to the 12th century BC, is one of the largest gold bracelets of the proto-Dacians found to date. It is made of large gold sheet of 580 grams (1.27 pounds) in weight and decorated with ten buttons fixed into holes, five on each end.[44][45]

Bracelets from Băleni, Galaţi (Late Romanian Bronze Age, Noua Culture) are particularly interesting because of their geometric décor, bands of right or oblique lines. They all have a green patina ranging from dark green to dull green, bluish green, bluish gloss.[46]

The fragmentary iron bracelet from the cremation cemetery found at Bobda is among the few unequivocally dated iron objects equivalent to Hallstatt A 1–2 in this region.[47][48]

A bracelet with snake-shape endings had been found at the Hallstattian necropolis in Ferigile (Vâlcea County).[49]

Spălnaca (Hopârta)

The bracelets from Spălnaca (Hopârta) are dated to Bronze Age IV (Iron Age I)[39] and have decorations of geometric characters. Although not directly influenced by the Hallstatt styles, the objects from Spalnaca pre-date the later tendencies for geometric surface decoration of chiseled or engraved lines.[50] Such discoveries at Spalnaca, Guterita and Dipsa show that bronze craftsmanship still flourished in the North Thracians from the Carpathian-Black Sea and Danube areas at the beginning of the Iron Age.[51][52]

Multi-spiral types

This type of Dacian bracelet originated in the Bronze Age.[43] The hoard found in 1980 at Hinova includes two such bracelets.[43] Multi-spiral types can be dated to the early Hallstatt periodand comprises also open and closed-end bracelets.[42] One of the spiral bracelets from Hinova weighed 261.55 grams and the other 497.13 grams.[43] The former, made of a thinner and narrower gold leaf, had a decoration consisting of two furrows cut along the edges and separated by a median crest.[43] A similar decoration, of a furrow along the median line, decorates a metal bracelet from the deposit found at Sânnicolau Român, dated to the second period of the Bronze Age.[43]

Finds from Dacia include spiral bracelets made of double gold wire, the largest of which weighed nearly a hundred grams. Gold spiral bracelets of this type have been discovered in Transylvania and Banat, spanning a long period which begins with the very late phase of the Bronze Age and ends with the middle Hallstatt. Similar pieces made of bronze were discovered in the deposit of bronze objects at Sacot-Slatioara.[54]

The multi-spiral bracelet type spans a long period of time that includes all Hallstattian stages.[55]

Spiral motif

The traditional ornamental motifs of bracelets, the meander and the "whirling" spiral (i.e. Oradea, Firiteaz and Sacosul mare), are thought to follow the spread of a cult of the sun, their decorations suggesting the rotation of the sun on the heavenly vault.[57] This motif is recognized as one of the parallels between the artifact decorations of this North Thracian group and the ornamentations from the Mycenaean Shaft Graves. It is found in both the Aegean and east-central Europe from the Neolithic onwards.[20]

Scholars opinions are divided on the source of these comparable traits. One opinion states that the North Thracian spiral motifs originate from the local Eneolithic (Chalcolithic) antecedents rather than from any imported influence.[19] There are specific forms widespread in northern Thrace that are unlikely inspired by the Mycenaeans.[19] It is also argued that these motifs apparently did not appear in the intervening territory of South Thrace.[20] With North Thracians, the spiral motif appears prominently in the form of massive armguard (armlet) terminals, offering physical as well as apotropaic protection.[20] Hoddinott states that the twin spiral terminals, as on the bowl from Biia, would have been a natural development; either from a local single armlet type or from an Unetice spectacle pendant.[20]

The other opinion attributes the spiral motif to a northward spread of Mycenaean influence.[21] It is argued that the spiral of the Neolithic period disappeared during the transitional period towards the Bronze Age, and even during the Early Bronze Age; therefore, starting from the Middle Bronze Age the spiral would occur because of a Mycenaean sway to the north of the Danube.[21] These comparable features might have been occurred because of commercial relations between the Mycenaeans and Dacians relating to the gold mines of Transylvania.[58]

Spiral ending types

Sacoşu Mare

Whatever may have been the origin of the spiral motif, the craftsmen of the late Carpatho-Danubian Bronze Age IV and Hallstatt A had a marked preference for bracelets with a spiral ending, as found at Sacosu Mare.[54] The same décor featuring the coiled disk endings of the single- or double-spiral bracelets is found on contemporary ceramics.[9] There is also a striking resemblance between the gold bracelets from Sacoșu Mare, from Firighiaz (or Firiteaz), and from other locations in Transylvania that suggest a spiritual affinity in the proto-Dacian world.[9]

The hoard from Sacoşu Mare consists of bracelets and jewelry dated to the 13th – 12th century BC (Late Bronze Age and Hallstatt I).[37] The golden bracelets, around 74.15 grams (2.6 ounces), have open ends of approximately 6.6 cm (2.6 inches) in diameter. Some terminate with convex volute ends,[37] while others have double convex volute ends.[59] The bracelet's bar is decorated with engraved rows of diamonds flanked by dotted lines.[59]

-

Gold bracelet convex double volute-ends Sacosu Mare, Timis County, Romania [36]

-

Sacosu Mare, 13th–12th century BC. NMIR Museum Romania[37]

-

Double-volute ends Sacosu Mare type. NMIR Museum Romania[59]

Firighiaz (Firiteaz)

The finds from Firighiaz (Firiteaz), Timiş County, on left bank of the Lower Mureş River, are representative of the spiral motif bracelets of this period.[8] [60] The Firiteaz's treasure contains twenty-three bracelets made of gold bar, each weighing 0.2 kg (0.44 pounds), and the hoard is housed in the Vienna Museum.[9] Bracelets made of bronze, similar to the Firiteaz ones made of gold, had been found in Transylvanian deposits dated to the Early Iron Age.[61]

The Firighiaz treasure comprises three types of bracelets:

- made of quadrangular cross-section bar; they are tapered at both ends (Type 1, dated to Late Bronze Age)[62]

- made of quadrangular cross-section bar; inverted spirals ends (Type 2)[60]

- made of semi-round cross section bar; these terminate with double volute spirals at each end (Type 3, dated to the 8th–7th c. BC)[60]

-

Firighiaz type 1, Late Bronze Age (Kunsthistorisches Museum – Vienna).[63]

-

Firighiaz type 2, 9th–8th century BC (Timis County).[63]

-

Firighiaz type 3 dated to 9th–8th c. BC. Kunsthistorisches Museum[63]

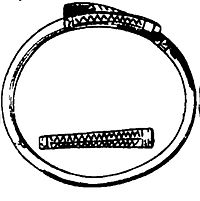

The earliest type one bracelets did not have ornamentations, while the later ones are engraved with groups of lines and angles or group of lines that alternate with lozenges (i.e. those from Sălaj).[64] This type is also common to the sites in: Domanesti (Sălaj County), Tăuteni (Bihor County) and Şpălnaca (Alba County).[62] Bracelets with quadrangular cross-section had previously been made of bronze, such as those at the beginning of the Hallstatt period. The gold ones are numerous, but are mostly of small dimensions; these smaller ones are considered to have been used as currency.[56]

The type two bracelets coil into spiral discs at only one end (terminal). At a later time, between the 8th and 7th century BC, they coiled at both terminals similar to the type three bracelets.[60]

The designs in type 3 bracelets, double-coiled (one at each of the two terminals), have also been found in bracelets from Biia (Alba County Romania), Fokoru (Heves, Hungary) and Bilje (Croatia).[60]

Spiral types similar to the Firighiaz type two have been found in a large area of Central and North-Western Europe: Bohemia, North-East Hungary, Moravia, Silesia, Poznan, West Poland, Pomerania, Lithuania, North Galicia, Germany (Bavaria, Wurttemberg, Turing, Mecklenburg) and Romania. Their prototypes may have been provided by the Lusatian Culture.[65] Some scholars believe that these bracelets were a kind of defensive weapon. This view is supported by the fact that this type was found usually on weapons deposits in Germany,[66] and that they appear to have been worn on the upper arm, as the traces of wear indicate.[67][66]

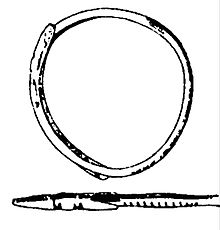

These locally-made bracelets from Firighiaz (Firiteaz), and from other Transylvanian finds, are half the size of the armlets of the similar style found in Germany and they could not be worn. It seems they were simple ornamental objects, a common trait to many similar items found in Romania.[66] Transylvanian bracelets of this type are described as nearly circular with 57 and 63 mm diameter. Their rods are of a circular cross-section (max. 10 mm thickness) gradually tapering towards the ends, where the cross-section becomes quadrangular and begins to curl in a spiral. The diameter of the spiral discs is 30–35 mm. Each of these discs are made from four spirals.[66]

Acâş and Săcueni

According to Pârvan (1928), the style of Firighiaz artifacts evolved over a considerable period of time into the later form styles of the Dacian Hallstattian bracelets as found at Săcueni (Bihor County), Pipea (Mureș County) and Biia (Alba County).[8]

Bracelets with double-volute ends like with Firighiaz type two, but with a different style, have been found at Acâş and Săcueni.[61] These are made of lozenge bar with a décor made of relief globule (similar to bracelets found at Saint-Babel) with double-coiled terminals.[68] The gold bracelets from Săcueni, as well as those from Acâş (Satu Mare County) and Hajdúszoboszló (Hungary) are typical Dacian bracelets of the Hallstatt period.[69]

-

Acâş- Săcueni are typical Dacian bracelet of Hallstatt Age[70]

-

Dacian gold bracelet Simleul Silvaniei (Crasna River (Tisza)) [71]

-

Gold bracelet Săcueni (Bihor County) Dacian-Hallstattian[70]

-

Dacian bracelet from North of Danube (unknown find spot).[72]

Bronze bracelets of this type had previously been found in deposits belonging to the first Hallstatt period. Their ornamentation and groups of motifs is similar to the Firighiaz (Firiteaz) type. Analogous bracelets had also been found at Oradea.[61] Two bracelets with spiral ends, dated to the Iron Age, have also been found in Dacian tombs of the Lower Danube.[73]

"Horn motif" from Pipea, Biia and Boarta

Bracelets from Biia and Pipea, found in 19th century, have an unclear chronology.[74] This series comprises a find from Abrud and another from an unknown Transylvanian location.[75] Some archaeologists are reporting them as dating to the Hallstatt,[76][10] though Márton (1933) dated them to the early La Tene period.[77] Popescu (1956) estimates these can be dated to the Hallstat phase B (1000–800 BC), but no later than C (800–650 BC).[74] whereas Mozsolics (1970) dates them to 1,500 BC.[11] The so-called Biia bracelet was found with the Biia gold "kantharos" that can be dated between 1,500 and 1,000 BC.[78] The handles of this goblet are also coiled into a double-spiral motif similar to other types of bracelets from the Carpathian area (i.e. Firigiaz 3, or Acas-Sacueni).[79]

There, specimens are made of bronze and are prototypes of the Pipea–Biia–Boarta series of bracelets; therefore, scholars agree these bracelets had been made locally, in the Transylvanian goldsmith workshops. This opinion is supported by metal analysis.[80]

These types of bracelets are possibly votive offerings, reminiscent of the cult of the bull.[81] Their common trait is the stylized motif of "horns". All of them have large C-shaped "horns" as terminals.[75] As with the spiral, Hoddinott purports that the east-central European bronzesmiths used this horn symbol to provide the warrior with both physical and deistic protection.[82] In the Aegean Shaft Graves it occurs only on a stele, a gold bowl and three pairs of gold earrings, which Hoddinott considers to be possibly of central European origin.[75] This thematic motif of the Carpathian peoples is confirmed by other archaeological finds from Transylvania that include three large rings weighing between 0.20 kilograms (0.44 pounds) and 0.60 kilograms (1.32 pounds). Their terminals are animal heads facing each other, depicting the heads of horses in two cases and bulls-heads in the third.[83] Eluere (1987) identifies the endings of the Pipea-Biia bracelets with the cultic and religious powerful horns of the bull, and estimates that this myth was perpetuated for centuries.[83]

-

Gold bracelet found at Biia Romania; dated to Hallstatt; National Museum, Budapest Hungary[84]

-

Bracelet from unknown Transylvania findspot[84] It belongs to the series of bracelets from Pipea – Biia – Boarta

-

Solid gold bracelet from Pipea Romania, dated to Hallstatt[10]

-

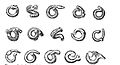

Decorative motifs of bracelets from Biia-Pipea[85]

-

Dacian bracelets found in Transylvania Romania – reposited by Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

According to Hoddinott (1989), the horned animal cults that are attested with these horns motifs were brought by the transitional Indo-Europeanization period immigrants who adopted these stylized motifs as their main apotropaic symbol;[19] however, the symbols of the horned animal replaced the local ones but were later associated with the sun-fire symbols of the earlier culture.[86]

The bracelet from Bilje (Croatia) belongs to the same Biia-Pipea type.[81] Hartmann noted that the percentage of silver and tin in the bracelets from Belly (Croatia) and Pipea (Romania) is almost identical. This suggests both bracelets had been made in the same region.[80] According to Marton, the armlets with semi-moon ends are part of an evolutionary series that terminates with the later silver snake-headed bracelets of the Classical Dacian times.[77]

Boarta type

The bracelet from Boarta (Şeica Mare-Sibiu County) was discovered in 1891 and is dated to 600 BC. It might be an example of the last phases in the evolution of the Biia-Pipea gold artifacts (For the photo of Boarta bracelet see the gallery of links [87]) A very similar copy of the Boarta type has been found with the treasure from Dalj, Slavonia.[88]

Unlike the Biia-Pipe type bracelets, the Boarta bracelet is flat, band-shaped, and has three raised ribs resembling the body of two other bracelets from Oradea. Its semi moon-shape terminals are smaller than the Biia-Pipea terminals;[88] thus, some scholars derive the type of the Boarta bracelet to be from some earlier bronze bracelets whose ends widen and whose bodies have more ridges.[89]

It seems that some other bracelets found at Bihor, Oradea, Targu Mures and Faget could possibly belong to the Boarta type, and not to the Biia-Pipea type.[88]

-

Mosna 1 – A Dacian gold bracelet dated to the Hallstatt period. Mosna, Sibiu County[91]

Mosna, Sibiu County

The terminal adornments of this gold bracelet look like animals' heads, but the zoomorphic motif almost disappeared because of the geometric stylization (see picture Mosna 1 above). It is dated to the Hallstatt period. This is not an isolated item, since it is stylistically connected to the geometric and zoomorphism of a collar and two bracelets from Veliki Gaj (Hungarian Nagygáj, Romanian Gaiu Mare) in Serbia.[92]

Zoomorphic bracelets

In the past, on the basis of a relatively small selection of archaeological finds, some scholars considered that the art of Geto-Dacians was geometrical and non-iconic. This led to the zoomorphic representations of Dacian bracelets being seen as an expression of the art of the steppes people, and Scythian art in particular. The majority of archaeological finds to date show that the main aspect of Geto-Dacian toreutics is in fact a zoomorphic motif style of its own.[94] This Dacian style of animal art occurs at the time when various ancient historical sources begin to record the Geto-Dacians as an ethnic entity of the larger Thracian family; therefore, this artistic expression might be considered as specific to the Dacian society of the last centuries BC.[94]

Some scholars sustain that the zoomorphic motifs of that particular time do not represent any kind of zoolatry of the Geto-Dacians. These would be iconographic motifs highlighting and multiplying certain attributes of the deities or of the kings.[95]

Ox-headed bracelets (Târgu Mureş, Apoldu de Sus, Vad)

The tendency towards the apotropaic zoomorphism that crystallized at the end of the Iron Age I (i.e. bracelets from Biia, Pipea, Boarta etc.) is clearly manifested with the bracelets possessing ornamented ox heads of the Iron Age II (La Tene) from Târgu Mureş (Mureş County), Apoldu de Sus (Sibiu County), Vad (Braşov County) and one from an unknown Transylvanian find.[96] The bracelet from Apoldu de Sus seems to have an ox head at one terminus and a ram's head at the other end.[97]

The ox-head bracelets have been associated with the clay Hallstatian’s Moon idol, with which they undoubtedly share a similarity.[89]

The wires of these series of bracelets are thick, and decorated with ornamental protrusions.[97] Their characteristic decor consists of relief or incised circles, while there are also those with cuts or incisions that form a fir-tree motif.[96]

A bracelet with ox-heads discovered in 19th century at Târgu Mureş (see picture) had been dated by some scholars to La Tene.[98] Others such as Popescu (1956) dated this particular one to the last period of the Hallstatt, since it might have been deposited together with a semi-moon type bracelet of that period.[74] As for the technique, it is noted that the bracelet from Targu Mures show a control of three-dimensional modeling,[99] with silver inlays.[100] There are two other bracelets of a similar type in the Transylvania Museum, though they are known to be discovered in Transylvania the original site is unknown.[88]

The religious meaning of the sacred horn had been lost over time, the circlets keeping this shape can only be described as decorative ornamentation.[89] The bracelet found in 1817 at Vad–Fagaras (Brasov County) terminating with horse heads depicted as wearing a bridle, is part of the general trend of bracelets replacing the sacred horn as a motif.[89][101]

Băiceni bracelets

In 1959 two bracelets terminating with "horned-horses", were found at Băiceni (Cucuteni).[103] They are dated to the end of the Iron Age I[36] and are found in the context of a hidden treasure of a Dacian nobleman.[104] The treasure comprised 2 kilograms of gold ornaments; a helmet, necklace, appliqués, harness, and buttons for vestments. They were ceremonial ensemble for kings or noblemen and their horses.[105] The bracelets and necklace terminate with protomes of horse heads and exhibit strong Thracian roots.[106]

The heads have also been interpreted as goat-heads (ibex).[36] Each head is very made of embossed gold foil with a filigree composition,[107] and had sun-symbols on the middle of the forehead. They also have what may be seen as ram's- or goats-horns (see picture "Head 1" on the right).[103] These Băiceni gold artworks of the 4th century BC are viewed as one of the links transferring the Thracian and North Thracian Art forms and motifs across to the Dacian silversmiths.[108]

Iron Age II (La Tene)

Dacians replaced gold, the popular Transylvanian metal during the Iron Age I period, with silver during Iron Age II.[109] The types of ornaments also changed, perhaps due to new social structures and hierarchy or due to changes of the preferences of the populous and sacerdotal aristocracy.[110]

Dacians absorbed influences from the western Celts and eastern Scythians, but also proved their artistic originality.[111] The bracelet style of the former is more individual, as they synthesized the older local elements originating from the Bronze Age into a new combination adapted to include the contemporary decorative forms and motifs.[111]

Objects specific to warriors (armors, harnesses etc.) became preponderant from the 5th century BC onwards, in contrast to the decorative objects (bracelets, torques and pendants) that predominated in the Bronze Age, and in the transition period leading up to the Iron Age.[94] In the 2nd and 1st century BC gold and silver military objects are replaced so that the treasures of the late Dacian La Tene comprise ceremonial ensembles of silver ornaments and clothing accessories, bracelets along with some mastos or footed cup vases .[112][110]

The geometrical and spiral motif ornamentation of earlier bracelets is more often replaced with zoomorphic and vegetal representations.[94] The decorations of bracelets that have been found, across the whole territory inhabited by Dacians, consist of lines cut into fir-tree shapes, dots, circlets, palmettes, waves, and bead motifs.[113]

Toteşti bracelet

Various single-spiral bracelets made of solid quadrangular (rhombic) gold bars, whose overlapping ends represent the head of a snake, were found in 1889 at Toteşti in Hunedoara County.[115][116] The head is geometrically stylized but clearly defined by decorative details. This artifact belongs to the so-called "Classic Dacian" period[116] and described as a "primitive work done by a not skilful hand".[citation needed] It was noted that the snake head is realistically depicted by the representation of the eyes, ears and other elements of the vipera ammodytes that is so commonly found in the area. The same scholars related these gold circlets to the later silver multi-spirals snake protome and palmette bracelets from Vaidei-Romos, Senereuş, Hetur, Marca and Oradea Mare.[115] Other scholars consider that Toteşti snake-headed ornaments should be interpreted on the basis of an abstract contemporary stylistic type, and not as an imitation of reality. In this interpretation Toteşti bracelets are not connected with the snakes from the region of Deva, but they are a tradition that began in Hallstatt times with the "Scythian rings" and continued into the La Tène period.[114]

In the Scythian tombs of Northern Hungary that are related to the Scythian invasions from around 700 BC, as well as in those of central Romania, spiral-shaped rings known as the "Scythian rings" have been found; with one end forming a fantastic animal, such as a dragon or serpent. These apotropaic creatures, themselves Turano-Siberian varieties of old Mesopotamian monsters, might have provided the model for the Dacian protome bracelet from Toteşti[117]—but neither the Scythian animals nor the Greek decorations appear to have had great success in Dacia, since the native geometric style continued to predominate.[118]

Analogies to the Totesti bracelets can be found not only to the multi-spiral bracelets, but also in the overlapping-end bracelets whose ends sometimes terminate with stylized animal heads.[38]

Common Dacian types of the La Tene IB (250–150 BC)

The archaeological findings dated to this period of time comprise the following types:

- One-spiral bracelet made of bar with engraved ends (mostly Hatching and Zigzag)[120]

- Bracelets with non-joined ends. It originates from Bronze Age i.e. from Spalnaca type [119] [121]

- Bracelet made of bar having a plastic decoration of a Celtic type "S", i.e. Gyoma[120]

- Bracelets with overlapped ends (i.e. Slimnic (Sibiu County) and Sâncrăieni (Harghita County).[119] [121] These are artifacts of local Hallstattian tradition originating from the first period of the Iron Age, and preserved until the late La Tene period.[122][121] Analogous models dated to the late Hallstatt period have been found at Balta Verde and Gogosu (both in Mehedinti County).[122]

- Bracelets with slightly widened or thickened ends.[123]

- Multi-spirals bracelet found with Slimnic treasure.[46] This is a re-adaptation of the older Carpathian spiral bracelet, earlier forms of it have been found in Bronze Age deposits at Balta Verde and Gogoşu (Mehedinti County).[121] This type could be considered as being just a simple form of the multi-spiral with protomes and palmettes.[122]

Bracelets in the "Classical Dacian" period of the Dacian State

The Dacian silver bracelet is one of the characteristic artworks of this period, and the most representative ornament on them is the snake protome.[124][29] Dacian bracelets have mainly been thought of as women's adornments but it can not be excluded that some types of bracelets, especially the multi-spirals ones, represented insignia of politico-military and sacerdotal functions and therefore worn by men.[125]

Bracelets became part of the objects that Dacians selected as votive offerings deposited outside settlements. Such offerings have been found in a fountain at Ciolanestii din Deal, Teleorman County, where silver bracelets and vases dated to 2nd–1st century BC were found, and finds beside a lake in a forest at Contesti, Argeş County, where bracelets, pearls, and a drachma were found.[126]

Types of the La Tene II period (150 BC – 100 AD) include:

- Bracelets with the ends curled back around the bracelet's wire i.e. Cerbal (Hunedoara County) and Remetea (Timis County)[119] [121]

- Bracelets made of multiple twisted wires i.e. at Cerbăl[120] In the La Tène Age, this type appears to have been developed from the twisted types of the Bronze Age IV from Spalnaca.[127]

- Bracelets with double torsade i.e. Cerbăl[128]

- Bracelets made of decorated band with circles and dotted lines i.e. Cerbăl[120]

- Bracelets made of ribbed bar[120]

- Bracelets with single- or multi-spirals terminating with snake heads[124]

-

Dacian bracelet from Transylvania; each end is coiled on the circlet's wire itself La Tène III [129])

Regional finds

According to Horedt (1973), silver Dacian treasure finds can be typologically categorized into north and south groups, divided by the Târnava River. In the contact zone between them the artifacts are common to both zones.[131] In this classification the silver multi-spiral bracelets that are ornamented with palmettes and snake protomes would belong to the southern group.[131]

East of the Carpathian Mountains

The Dacian bracelets that have been found East of the Carpathians can be categorized into two main types:

- Non-joined ends i.e. those found at Poiana (Galati County) and Gradistea (Brăila County). Numerous specimens are made of bronze, such as those found at Brad, Racatau and Poiana.[132][133]

- Overlapped ends that are coiled onto the wire itself.[132] [133] This type has ornamentation consisting of geometrical motifs and sometimes of snake protomes.[133]

The characteristic metals used for bracelets found in the area of the Siret River valley are bronze and iron,[132] though silver was also probably used; a silver bracelet was found with a treasure of coins buried after 119–122 AD.[131]

In the Prut-Dniester region sub-types have been identified such as:

- Bronze bracelets such as those found at Trebujeni, Maşcăuţi and Hansca

- Non-joined ends, bar with vegetal décor such as those from Palanca-Tudora

- Bracelets made of 3–6 twisted bronze wires with flattened ornaments in the middle.[134]

- Multi-spiral types, such as the bracelets from the treasure found at Mateuţi (Rezina District) dated to the 4th century BC. This treasure includes two silver bracelets, one with five spirals and one with three.[135]

Moesia Superior

Dacian bracelets have been found in deposits from Tekija, Bare (Serbia)[136], Veliko Središte[137] and Paraćin.[138]

The style and type of the bracelets from Tekija and Bare are similar to the Dacian silver types; i.e. bracelets made of twisted wire and bracelets with overlapped ends that are coiled around the wire itself.[136] Even though the origins of this type should not necessarily be located in Dacia itself, since bracelets of this type are scattered throughout the entire Balkan-Danube area, the earliest dated bracelets from Tekija and Bare are very large, as were those typical of the Dacian cultural complex.[139] Bracelets with ends shaped as a head of, or tail of, a serpent are well represented in the Dacian deposits that are found at the Bare.[139]

The Dacian bracelets that are decorated with spiral end-pieces, i.e. Belgrad—Guberevac (Leskovac), along with thin Dacian silver necklaces found in East Serbia, characterize the presence of a Dacian La Tene culture at Paraćin in Serbia.[138]

-

Silver bracelet - Transylvania (Iron Age II) [140]

Bracelets with cord ornaments

An important category of the jewelry in the Daco-Getic environment are bronze bracelets with cord ornaments, whose typology consists of three types held in the Blaj Museum and in Simleul Silvaniei. Such circlets had been discovered at Ardeu, Cuciulata (Brasov), Costesti (Hunedoara), Ocnita (Valcea), Pecica (Arad), Simleul Silvaniei (Sălaj), Tilisca (Sibiu) and in the Orăstie Mountains.[141] These ornaments do not seem to be specific to pre-Roman Dacia, as they were widely spread in contemporary Germany, Poland, Czech, Slovakia, Hungary and Slovenia—all during the La Tene period.[142] Since their diameter is around 10 cm, apart from those found in Simleul Silvaniei and Orăstie which are 6 cm and 7.5 cm, they were probably worn on the arm or as anklets.[143] They have been found mainly in fortresses or important centers of pre-Roman Dacia, and appear to have been prestige items of the local aristocracy.[143]

Bracelets with a double torsade

This type have been found with treasures from Cerbăl (Hunedoara County), Bistrita (Bistriţa-Năsăud County), Drăgeşti (Bihor County), Oradea-Sere (Bihor County), Saracsău (Alba County), and Tilişca (Sibiu County). The bracelets are made of wire turned two or three times to form a semicircular terminal. The three-turns style is seen only with a single bracelet from Cerbăl. These terminals are always decorated with stamped-dotted lines and are dated to the 1st century BC.[128]

This type was designed and preferred by the intra-Carpathian regions. Only one presence occurs in the Danube area, at Iron Gates.[144] Since this bracelet appears to have been a prestige ornament, its presence south of the Carpathians is seen as a component of the relationships between the elites of the two neighboring regions.[144]

The material of bracelets

In the Bronze Age IV and Hallstatt periods Dacia was characterized by gold treasures and by a particular gold art, whereas archaeological finds dated to the La Tene period are mostly made of silver.[145][34] This is a common characteristic of the Illyrian and Eastern Alps regions of the time, and not limited to the Dacian area.[145] Some scholars, such as Glodariu, explain the scarcity of gold ornaments and bracelets in Dacian treasures by a custom of the Dacians, Celts, Germans and Romans in reserving golden ornaments for the king alone.[34] Other scholars, such as Florescu, put forth the hypothesis of religious restrictions regarding the use of gold in the period of the Dacian state.[146]

The golden Dacian bracelets, and indeed most of the jewelry, that has been found so far are made of unrefined gold from the Apuseni Mountains.[147]

The silver of the Dacian bracelets and other ornaments of the time always contain between 0.63 and 6.35 % gold.[148] In some scholars opinions, such as Oberländer-Târnoveanu, it was obtained by melting Greek and Roman coins as well as importing from Balkan sources.[147] Others, Popescu for example, support the thesis of a local extraction of silver from the Apuseni Mountains.[149]

The work and typology of the silver multi-spirals snake-headed bracelets suggests the existence of a large manufacturing center, located most probably near the Dacian cites of the Orastie Mountains.[150] From there silver artifacts spread throughout the entire area of modern-day Transylvania; and, as archaeological finds prove, these art works become later known in areas that encompass the modern regions of Moldavia, Muntenia and Oltenia.[150]

In the second phase of La Tène, reasoned on the basis of finds, Dacia appears to have experienced a temporary "silver crisis", probably related to an increase in the minting of silver denarii; therefore, bracelets dated to that time had been made of mild alloy and only plated with a silver layer about 0.1 mm (0.004 inch) thick. The layer was so well welded that the welding can not be identified by the naked eye, even in cross sections.[26] Specimens of the group include finds from Sarmasag (Salaj County) and Dersca (Botosani County). Ther were also similar finds at Slimnic (Sibiu County) and Herastrau Bucuresti.[151]

A gilded silver belt fragment Cioara – Alba County dated La Tene depicts warriors wearing bracelets[152]

A gilded silver belt fragment Cioara – Alba County dated La Tene depicts warriors wearing bracelets[152]

Representations depicting the wearing of Dacian bracelets

The Dacian phalera from Lupu-Cergău, Alba County, depicts a feminine divinity wearing some circlets on her arms. Some scholars identified these with a representation of the Dacian bracelet types.[153][154]

In 1820 at Cioara (today Săliştea a fragmentary gilded silver plaque was discovered, dated to La Tène III, and primitively decorated au repousse ("by embossing"), with representations of two human characters, probably warriors.[155] Hatched bands are visible on the arms and wrists that resemble regular bracelets.[156] Even though the motifs of the plaque do not seem to be local, since it differs in some respects from those depicted on Trajan's Column, the silver-work itself seems to be Dacian. Other than the Dacians, no-one was working in this style at that time. The silversmith who made it is probably the same one who made the well known Dacian snake-headed bracelets from Hunedoara County.[157]

A fragment from the Forum of Roman Emperor Trajan (2nd century AD) in Rome has a relief of a seated female, probably a Dacian (Dacia Capta – "the conquered Dacia"). She is depicted wearing a bracelet on each arm below the shoulder.[158]

Bracelets with a snake-motif

This motif is found with both the multi-spiral bracelets and also with the simple bracelets.[159]

- Multi-spiral silver bracelets terminating with portions of palmettes and snake protome terminals at each end, i.e. those found at Cojocna, Bălăneşti (Mărunţei), Rociu, Coada Malului[123][160] Drauseni (Caţa) (destroyed by 1941),[161] Feldioara and Orastie.[162] The endings of some of the bracelets were gilded: i.e. Coada Malului [163] and Orastie.[162]

- Multi-spiral bracelets with snake-heads at each terminal, but whose terminals do not have the palmettes, that are plaques decorated with large scales, i.e. those from Herastrau (Bucuresti) dated to the 1st century BC.[160] A bracelet from Bunesti (Vaslui County) is similar to the one from Herastrau, but it is dated earlier than the 1st century BC.[164]

- Simple bracelets, where stylized snake heads terminate the ends.[123] The ends are either in the shape of an animal’s head summarily but adroitly stylized, as in the case of the Slimnic bracelets, or in other cases the animal's head is suggested by a few engraved lines, and the decorated ends were gilded.[7] Finds include those from: Ocnita (Valcea County),[165] Poiana (Tecuci),[166] Săcălăsău Nou (Bihor County),[167] in Romania; and also from Jakabszállás in Hungary.[168]

- Bronze bracelets cast and incised with snake protomes, i.e. those found in Râşnov, Braşov County, and dated to the 2nd–1st century AD.[169]

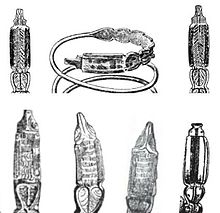

Description of the silver multi-spiral bracelets with palmettes and protomes at both terminals

There are about 27 known Dacian silver or silver-gilt multi-spiral bracelets terminating with rectangular plaques and snake head protomes. They are exhibited or kept in repositories and museums in Bucharest (Romania), Budapest (Hungary) and Belgrade (Serbia).[170] Additionally the Kunsthistorisches Museum holds Dacian silver bracelets such as the one found at Orastie (Hunedoara County)[171] and the one from Feldioara (Brasov County).[171][172]

All of these silver works are characterized by their large size. For example, the one found at Senereuş, now in the Brukenthal Museum weights aropund 0.4 kilograms (0.88 pounds). The wire used is 206 cm (6 feet 9 inches) long and 0.4 cm (0.157 inches) thick, while the heads are 21 cm each (8.26 inches). The inside diameter of the coils is 12.5 cm (4.92 inches) with an outside diamter of 13.3 cm (5.2 inches). These large diameters and the heavy weight of these armlets would suggest wearing them on the upper arm or on the leg.[173][174] The coils of the specimen from Cluj Napoca have an even bigger outside diameter at 16 cm (6.3 inches);[162] therefore, it is supposed that it was worn on the thigh or forearm over clothes[7]

The specimen from the Transylvanian Museum at Cluj weighs 0.358 kilograms (0.79 pounds). It has been made by hammering a silver bar of a circular cross-section. It has 4 spirals and the ends are flattened, decorated with seven palmettes made by punching. The surfaces of the palmettes, and their extremities, are decorated with the "fir-tree" motif and incised circles.[175]

The multi-spiral from Belgrad Museum has an interesting particularity in that the impression of the palmette motif has two puncheons of different dimensions. This might have been done in order to avoid the stereotypy of models.[137]

Origins

Snakes are depicted in Dacian toreutics from the 6th–5th century BC, and also in the later period.[176] Both types of bracelets with snake protomes, those of simple and multiple spirals, show an ancient Thracian tradition from the Hallstatt period (the Geto-Thracian period) of Geto-Dacian art evolution.[177] Snake-shaped bracelets, and other ornaments of the same kind, speak not only of the spread of the decorative motif but also of a symbol and significance of this motif in the Dacian period.[178]

Some scholars suppose that the Scythians provided the model of the snake décor found in the Classical Dacian bracelets, on the basis that the semi-spiraled Scythian snake type rings, were common in Dacia after the Hallstatt period. Those rings might have been continuously used until the La Tène period, or perhaps until the Roman era, as can be seen with a necropolis from Caşolţ, Sibiu County.[159][179]. If this was the case, Shchukin suggests it was a matter of transferred ideas rather than of imports.[180]

These bracelets types can be explained by the typology of the local tradition of the Hallstattian period; and there were similar bracelets in the Thracian world of today's Romania and Bulgaria.[177][108] Such examples include a mid 3rd century BC spiral dragon-headed ring; a spiral snake-headed ring from Nesebar (Messembria); 4th century BC spiraled bracelets from Aitos; and a 3rd century BC snake-headed ring of unknown origin in the British Museum.[108]

The manufacture of the spirals, by wrapping the silver wire several times, belongs to the traditions of the Bronze Age;[181] but those with their ends flattened, and decorated on the outside with intaglio palmettes, belong to a more modern style according to Popescu.[182] The way in which these dragon patterned bracelets were developed by the Dacians was new, while its resemblance to the workmanship and style of other countries are so few, that these bracelets might very well be considered as specifically Dacian. It can be distinguished as a Dacian style since they remained faithful to their own geometric representations,[183] and the palmette motif is not found in the neighboring areas.[137]

-

Dacian silver bracelet dated 1st c. BC; Museum of Transylvania Cluj-Napoca.[184]

-

Scythian Hallstatt Scythian type rings from Dacia, believed to be a "source" for Dacian snake-headed bracelets.[185]

-

Silver ornament found at Dârlos (Sibiu County)[186]

-

Bracelets Vaidei (Hunedoara County) and Hetiur (Mures County).[187]

-

Detail, snake-head and rectangular plaque 'mane' of the gold bracelets 1st c. BC [2]

-

Protoma head and mane of a gold bracelets 1st c. BC Sarmizegetusa [2]

-

Silver Dacian bracelet from Transylvania (La Tene age) National Museum – Budapest.[140]

The dragon and snake-head motif

Within the multi-spiral group of bracelets with palmette scales, two sub-groups can be stylistically identified – one represented by the Feldioara find and the other by the Orastie find. These sub-groups show that the snake and dragon types were not absolutely immutable in the imagination of the Dacian silversmiths. Two variants were introduced: mammal head – snake head and crest – mane,[108] as well as some transitional versions.[188]

Details of the "dragon" head of both ends; Silver bracelets from Hetur, Vaidei (Romos) and Darlos Romania[189]

Details of the "dragon" head of both ends; Silver bracelets from Hetur, Vaidei (Romos) and Darlos Romania[189]

The bracelet discovered around 1856 at Orăștie consists of a single silver wire, with a circular cross-section, coiled into eight equal spirals terminating in a dragon head at both ends. It is analogous to the bracelet from Feldioara but its head is different in that the head is almost triangular.[190] It has been made in a richer figurative manner than others.[191]

The multi-spiral bracelet with zoomorphic (snake?) ends, found in 1859 with a treasure from Feldioara, is different because of the widened muzzle of the protome terminals. In the middle of the snake head the Dacian silversmith engraved braids, by the use of puncheons, consisting of two rows of small, oblique, divergent traits. The snake's eyes are depicted as two circles. A strong profile separates the head from a relatively rectangular plaque with rounded corners, and slightly arched edges representing the mane of the Dacian dragon. The profiled relief edges of the bracelet's rectangular plaque and its decoration with two rows of divergent slashes are suggestive of the mane of a dragon or wolf.[192]

The bracelets from the Museum of Transylvania found in Cluj, Hetiur (Mureș County) and Ghelința are characterized by a more trenchant cutting and a more prominent relief for modeling the head. These traits are unlikely to represent a specific ophidian form and the longitudinal axis is marked by a stylistically different means.[188]

The zoomorphic motif of the bracelets depicts a fantastic animal with the head and body of a serpent but the muzzle of a mammal, pointed or square, with a thick mane flowing on its back prolonged by a poly-lobed (multiple palmettes) body. [192][183] The analysis of these Dacian symbols, performed by scholars—such as Florescu (1979), Parvan (1926), and Bichir (1984)—conclude that the symbol of the snake or dragon appears on the Geto-Dacian La Tene bracelets and on the Dacian standard (flag) that can be seen on Trajan's Column.[192][183][193] The Dacians dragon probably combines two meanings: the agility and redoubtable ferocity of the wolf with the protective role of the snake.[194] It was supposed to encourage the Getae and to scare their enemies.[195] It also appeared to have been the only one known representation of the religious character of the Dacians of the time.[196] Scholastic interpretations vary between considering this a representation of a "flying dragon", related to a Sky God,[197] or a chthonic symbol.[198]

Some bracelets from south of the Carpathians, such as those from Coada Malului, Bălăneşti and Rociu; and some from north of the Carpathians such as those from Dârlos and Vaidei (Romos)) do not have decorative elements to mark the median line on the rectangular plaque (the wider and flat portion coming next to the head). They instead have wavy lines, finely engraved, suggesting a mane or ridge.[199] A similar style is seen in specimens from Senereuş, Dupuş (Sibiu County) and from the unknown Transylvanian site, the fragment of which is kept at the Budapest Museum. On the latter, the beam of wavy lines has been replaced by horizontal, short and dense, finely engraved lines.[199]

The rectangular portion of the bracelets from Bălăneşti and Transylvania show a tendency to split into two teardrop-shaped lobes.[199] On the subgroup of bracelets from Coada Malului, the fir-tree is depicted only schematically.[199]

It was also noted that the snakes from the Agighiol artifacts of the 4th century BC, especially the depicted heads of snakes, have a stylization similar to that of the Dacian bracelet protomes; they have the same triangular form, and the same distribution of the decorations that mark the eye of the snake.[177]

The leaf motifs of the multi-spiral bracelets

Detail: the fir-tree motif and the rectangular portion of the silver bracelet (1st centuryBC) repository Cluj-Napoca Museum[184]

Detail: the fir-tree motif and the rectangular portion of the silver bracelet (1st centuryBC) repository Cluj-Napoca Museum[184]

The flattened bands of the bracelets are decorated externally with a chain of geometrized palmettes that have been struck in much the same way as coins.[183] It seems that the leaf-like ornaments have been made by impression, using ready-made moulds, as used in the manufacture of Dacian cups from the La Tène Crasani (com. Balaciu) site. Scholars, such as Popescu, related the chain of successive palmettes of the Dacian bracelets to the decoration of the borders on the Scythian Melgunov dagger sheath from the 6th century BC.[182] Others consider that several multi-spiral bracelets, i.e. from Balanesti (Olt), have the same palmette motif as the typical decorations of the 4th century BC Thracian-Getic helmet from Agighiol (com. Valea Nucarilor), Tulcea.[200] In the opinion of Berciu, the palmette motif was adopted from the Greeks of the Black Sea coast during the Geto-Thracian Art period.[177]

Dacian bracelets exhibit four decorative types of leaf-like triangular lobes: first is the most complex is of oval or triangular palmettes; the second is interpreted as representing fern leaves (e.g. the Orastie bracelet); the third is the fir-tree motif, where the rounded lobes become straight lines resembling a fir-tree branch; and the fourth whose shape preserves only the medial vein and the circles, suggesting the spiral arching of the lobes (e.g. the Feldioara bracelet).[192]

The palmettes are more precisely outlined and more faithfully preserve the original lobes and palmette character, with several bracelets such as those from the Cluj Museum, Hetiur and Ghelinta. They are farthest away from a schematic fir-tree motif.[188] A stylized ivy leaf-like style is common to the group of bracelets from Coada Malului, Rociu and Bălăneşti (Arges County), and Dupuş. It is formed using carved lines doubled with a fine series of dots.[108]

The same motif seen in other ornaments

The decorative snake style has been adopted in other types of ornaments, such as earrings from Răcătău and spiral rings from Sprâncenata and Popeşti-Novaci.[201]

The silver ring from Măgura, Teleorman has four-and-a-half multi-spirals with snake-head terminals and a chain of five palmettes.[202] It belongs to a small silver treasure—comprising three denarii that could be dated between 148–106 BC, and one ornament (the ring)—fortuitously discovered in 2005 and 2006 in a spot 330 m from Măgura village.[203] The ring is considered by some, e.g. Mirea (2009), to be a miniaturized representation of the typical multi-spiral bracelets terminating with palmettes and snake protomes.[204] There are particular analogies with the bracelets from Bălăneşti–Olt and Rociu–Argeş; as well as analogies with the spiral rings from Sprâncenata and Popeşti.[204] The decorations are similar to a motif of the gold multi-spiral bracelets discovered in 1999–2001 at Sarmizegetusa Regia.[204]

Significance and archaeology of the silver multi-spiral bracelets with palmettes and protomes

The multi-spiral bracelets made of plates with zoomorphic extremities, all of them made of silver and sometimes gilded, are characteristic of the north-Danubian Dacian elite, in particular ones from Transylvania.[206] Also, according to Medelet (1976), one Dacian silver bracelet from Malak Porovets (Isperih Municipality Bulgaria) and one Dacian silver bracelet from Velika Vrbica (Serbia), belong to the same typology.[205] Some of this type of bracelets, such as the one in the Cluj-Napoca Transilvanias History Museum and the two others in the National Museum Budapet (Hungary), are from unknown Transylvanian sites.[108]

It is possible the big silver multi-spirals were used with clothes worn for special celebrations,[201] though they do not seem to have a simply decorative use.[207] [208] The context of burying these prestige aristocratic insignia suggests that the treasures they compound were rather votive deposits than funeral offerings (cenotaph?).[209]

The silver snake-headed multi-spiral bracelets are found in the context of the so-called Dacian silver treasures.[210] A significant fact regarding these treasures is the specificity of the time frame, from around 125 BC – 25 AD (one century).[211] In historical terms, they are contemporary to the reigns of Burebista, Deceneus and Comosicus. It is probable that the hoards of silver bracelets and ornaments of the late Geto-Dacian began to be produced just prior to the reign of Burebista, a possible example being the one from Sâncrăieni. The manufacturing of silver ornaments continued during his reign, although to a lesser extent (perhaps due to his authoritarian, despotic and purist nature), and mostly after his suppression of the manufacture (44 BC – 46 AD); therefore the silver hoard production lasted almost a century.[212] The burying of these Dacian silver jewelry items and bracelets (those made between 44 BC and 46 AD) occurred in the same period of time that was characterized by a scarcity of silver due to the turbulent situation in Dacia.[212]

This particular type of design has an unitary typology and a highly standardized character. It does not contain goods that had been accumulated over years, but only sets of certain objects.[211] Also, they have not been found in the context of settlements but outside them, on carefully prepared deposits.[213] These objects had not been temporarily concealed or hidden, because of some exposure to dangerous situations, but they were rather supposed to preserve the symbolic attributes of the social status in the afterlife.[153]

Several Dacian bracelets reached the collections of the Kunsthistorisches Vienna Museum through various channels: administrative, auctions, purchases, and donations. Though they were found in Transylvania, and belong to the similar archaeological context of the other Dacian silver treasures, they are rather accidental discoveries from the west and south of the Transylvanian plateau—both in the areas of the greatest concentration of Dacian culture in the Orăştie and Apuseni Mountains, where precious metal mineral deposits were, and are, to be found.[214]

Gold multi-spiraled dragon-headed and animal protome bracelets

Gold artifacts in general, and gold bracelets in particular, have been scarce archaeological finds during excavations. An explanation could be that the Romans collected all gold objects by force after conquering Dacia.[32] Some, including Manaila, explained the scarcity of these kinds of archaeological finds as due to Dacian religious reasons, all gold being collected by the priests and given to the Dacian king.[32] Numerous researchers, including Rustoiu, argued the existence of a royal monopoly of the gold and silver exploitation in Dacia;[215] and that after the Roman conquest, this monopoly passed to the Roman Emperor.[216]

Description

These gold bracelets, adorned with leaves and snake heads, weigh around 2.2 pounds (1 kilogram) each.[217] There are remarkable analogies between the gold armlets and those made of silver from Coada Malului (Prahova County), Senereuş (Hunedoara County), Orăştie (Hunedoara County) and Herăstrău-Bucureşti.[218] Most of them exhibit similar design and artistic themes, but there are no two identical bracelets.[219] The decorations on these bracelets is similar to the style of the ring from Magura (Teleorman County).[204]

One such bracelet recovered in 2007 has both terminals depicting a stylized animal head, which represents a snake with a long muzzle, and is decorated with arched lines. The rectangular plaque's surface is decorated with transverse rows of arched incisions, grouped in four and a half metopes. The body is composed of seven palmettes, consisting of a fir tree-shape, and a dotted line in the middle, while the terminals oppose each other.[3]

The number of spirals varies from six to eight. When uncoiled, some bracelets measure 2.30 m and others 2.80 m. The outside diameters range from 91 to 123 mm. The spirals consist of flat rectangular strips with richly incised decorations and stylized palmettes. In most of them, seven palmettes decorate both ends of the bracelets.[170] The bracelets terminate with a decorative protoma, a beast-head motif which looks like the head of an animal (a wolf, a snake or a dog).[219] The goldsmith technique, used for manufacturing all of these gold armlets, was the cold hammering of a rectangular-shaped gold ingot, followed by punching and engraving for their decorations. This was a typical method used by Dacians from the 4th century BC – 1st century AD.[170]

A bracelet recovered in 2009 has ten spirals. The terminals depict a stylized snake protome. The long muzzle is straight cut and the eyes and eyebrows are represented by curved lines. The head continues onto a rectangular plaque of 3.4 cm in length whose relief edges are decorated with incised oblique lines in a "V" shape, separated by a medial line. This is followed by a series of six triangular-oval palmettes, made by three puncheons, and with a length of 14.3 cm. The first puncheon made the first two palmettes, the second made the next two palmettes, and the third was used for the last—which is also the smallest palmette. The palmettes have a foliage design and their edges are raised and decorated with small incised oblique lines.[220]

Context

Some two dozen of the gold multi-spiral zoomorphic-headed bracelets were discovered by archaeological looting in different spots in the area of Sarmisegetusa Regia, in the Orăștie Mountains.[221] By 2011, twelve out of the twenty-four looted gold bracelets had been recovered and are housed at the Romanian National History Museum in Bucharest.[217]

An archaeological context has been reconstituted on the basis of a forensic science approach, technical description, and archaeological interpretation. The multi-spiral bracelets had been uncovered from pits near to the "Sacred area" of the Dacian capital at Sarmizegetusa Regia (Hunedoara County), around 600 m from the sacred enclosure. The pits are located on the steep rocky slopes outside the ancient settlements, in a narrow valley.[222] The bracelets site is located on a very steep and rocky area that involves a difficult climb and hinders "classical" archaeological approaches and research.[222]

The treasure hunters discovered a spot where they found ten golden bracelets in a pit dug into natural rock on a 70° slope.[223] The pit had two distinct overlapped cavities of triangular shape made of slabs, one containing six gold multi-spiral bracelets and the other four, that had each been deposited in pairs; the smaller bracelets were inserted into the larger ones.[224] The finding of bracelets on such steep sloping cliffs, and at the outer limits (eastern) of the settlements, provides a new perspective regarding the ancient sites used for depositing artifacts with special religious significance.[222] These deposits are composed of the same type of ornaments that have identical function and significance.[222]

The general circumstances of the placement of these bracelets, deposited by the ancient populous, in these specially constructed pits and covered with uncut slabs imply that these artifacts were components of votive offerings.[225][2] It seems as if these bracelets were used during initiations, or occult ceremonies, restricted to a certain category of people that had very important positions in the state: the king; the leaders of cities; the nobles from the royal entourage; and the priests.[225] This explains the existence of similar pieces made of silver for the leading nobles and rulers of the cities, and the lack of similar specimens made of bronze, iron or other metals. It also explains why these types of bracelet do not appear in written sources, nor the figurative representations of the time.[225]

Chronology and authentication

Based on typological analogy and stylistic analysis, historians believe that these bracelets are authentic Dacian artifacts.[226] Some chronological evidence is provided by dark blotches that indicate a long period of time underground, and also by the ancient coins that were found along with bracelets. These coins point to the late 2nd century BC and the first decades of the 1st century BC. It appears that the bracelets were buried, if not necessarily crafted, during a time frame between 100–70 BC.[2]

The chronology of these bracelets corresponds to the emergence of the building of religious sanctuaries, digging and arranging pits with a religious purpose where deposits of offerings to the chthonian gods had been made.[227]

In 2007 a compositional analysis of these gold objects was performed using a non-destructive method, particle-induced X-ray emission (micro-PIXE measurements) and synchrotron X-Ray fluorescence (SR-XRF) analysis.[228] More studies were performed in 2008 and 2009 by a team consisting of members from the National Institute for Nuclear Physics and Engineering, Romania, the National History Museum of Romania, and the BAM Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing, Germany. Researchers compared the gold composition, examining the trace platinum group elements, Tin, Tellurium, Antimony, Mercury, and Lead and comparing them with the corresponding elements of natural gold from Transylvania. This was done since these trace-elements are more significant for provenancing archaeological metallic-artifacts than the main element components.[219] For these studies, several small fragments of natural Transylvanian gold – placer and primary – were analyzed using: the micro-PIXE technique at the Legnaro National Laboratory AN2000 micro-beam facility, Italy, and at the AGLAE accelerator, C2RMF, Paris, France; and by using micro-synchrotron radiation X-ray fluorescence (micro-SR-XRF) at the BESSY synchrotron, Berlin, Germany.[219] The studies of the teams concluded that the gold multi-spiral bracelets found between 1999–2001 at Sarmizegethusa had been made of native Transylvanian gold and not refined gold.[228][229]

Because of the adverse conditions surrounding the hoard's discovery, their origins may never be authenticated to the full satisfaction of archaeologists and scientists.[217] Sceptics suggest that the bracelets could have been produced in modern times from metal obtained by melting ancient gold coins, Dacian coins of the KOSON type or Greek Lysimachus coins; however, the analyses performed so far do not confirm the use of gold from these coins in the bracelets' manufacture.[230]

It is most likely that no other group of ancient goldwork has been more thoroughly examined by scientists, technologists and scholars in various countries and various institutions than the Dacian gold spirals with dragon terminals found between 1999–2001 at Sarmizegethusa. In each case-study, and completely independent from each other, their examinations led to the same conclusion.[231]

Gallery – Iron Age II (La Tene) Gold bracelets

Notes

- ^ a b Trohani 2007, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Constantinescu 2010, p. 1040.

- ^ a b c Trohani 2007, p. 1.

- ^ a b Arbunescu 2011, p. 1.

- ^

For the various functions of bracelets with Dacians see Florescu et. al (1980) p.68

- For the high rank insignia, see Sîrbu and Florea (2000) p.13

- For the bracelets used as ornaments, see Dumitrescu H (1941), p.137

- For the votive offerings see Spânu (1998) p.49

- For the bracelet-currency see Popescu (1956) p.212

- For the North Thracians see McHenry Encyclopaedia Britannica (1993) p.602

- ^ a b Taylor 2001, p. 212.

- ^ a b c Popescu 1971, p. 45.

- ^ a b c d Pârvan 1928, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e f Burda 1979, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Şandric 2008, p. 2.

- ^ a b Mozsolics 1970, p. 143.

- ^ MacKenzie 1986, p. 25.

- ^ Giurescu & Nestorescu 1981, p. 47.

- ^ Dumitrescu & Boardman 1982, p. 53.

- ^ Hoddinott 1989, p. 52.

- ^ Cunliffe 1987, p. 59.

- ^ Dumitrescu 1972, p. 259.

- ^ McHenry & Encyclopaedia Britannica 1993, p. 602.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoddinott 1989, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d e f Hoddinott 1989, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Dumitrescu 1972, p. 258.

- ^ Megaw 1970, p. 32.

- ^ Sandars 1976, p. 51.

- ^ a b McKendrick 1975, p. 19.

- ^ a b Halbertsma 1994, p. 26.

- ^ a b Glodariu 1997, p. 25.

- ^ Sîrbu & Florea 2000, p. 69.

- ^ Oltean 2007, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Popescu 1959, p. 22.

- ^ Taylor 1994, p. 406.

- ^ Seculici 2008, p. 67.

- ^ a b c Manaila 1976, p. 90.

- ^ Constantinescu 2007, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Glodariu & et. al 2008, p. 146.

- ^ Coles & Harding 1979, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Florescu & et. al 1980, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d Leahu 2004, p. 1.

- ^ a b Popescu 1956, p. 227.

- ^ a b c d e Coles & Harding 1979, p. 409.

- ^ a b Tocilescu 1877.

- ^ Leahu 2003, p. =134.

- ^ a b c Laszlo 2001, p. 350.

- ^ a b c d e f MacKenzie 1986, p. 93.

- ^ Hagioglu & Gheorghies 2010, p. 117.

- ^ Leahu 2003, p. 1 poz. 134.

- ^ a b Vauthey P & Vauthey M 1968, p. 345.

- ^ Stoia 1989, p. 77.

- ^ Pleiner 1982, p. 168.

- ^ Vulpe 1967, p. 73.

- ^ Pârvan 1928, p. 12.

- ^ Popescu 1971, p. 37.

- ^ Petrescu-Dâmbovita 1996, p. 597.

- ^ Leahu 2003, p. 136.

- ^ a b MacKenzie 1986, p. 94.

- ^ Popa & Berciu 1965, p. 63.

- ^ a b Popescu 1956, p. 212.

- ^ Dragut & Florea 1984, p. 31.

- ^ Samsaris 1989, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Leahu 2011, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Dumitrescu H 1941, p. 141.

- ^ a b c Popescu 1956, p. 215.

- ^ a b Hortensia H 1941, p. 136.

- ^ a b c Parvan 1926, p. 326.

- ^ Hortensia H 1941, p. 133.

- ^ Hortensia H 1941, p. 140.

- ^ a b c d Hortensia H 1941, p. 137.

- ^ Childe 1930, p. 120.

- ^ Éluère 1982, p. 163.

- ^ Parvan 1926, p. 330.

- ^ a b Parvan 1926, p. 331.

- ^ cIMeC & 2011 Punct 19.

- ^ Linas 1888, p. 288.

- ^ Linas 1887, p. 288.

- ^ a b c Popescu 1956, p. 239.

- ^ a b c Hoddinott 1989, p. 59.

- ^ Şandric 2003, p. 2.

- ^ a b Popescu 1956, p. 222.

- ^ Eluère 1991, p. 7o.

- ^ Bouzek 1985, p. 52.

- ^ a b Kovacs 2001, p. 48.

- ^ a b Eluère 1987, p. 76.

- ^ Hoddinott 1989, p. 58.

- ^ a b Eluère 1987, p. 58.

- ^ a b Hampel 1881, p. 214-216.

- ^ Hampel 1881, pp. 214–216.

- ^ Hoddinott 1981, p. 165.

- ^ Wittenberger 2010, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Popescu 1956, p. 217.

- ^ a b c d e Popescu 1956, p. 221.

- ^ Eluère 1991, p. 76.

- ^ Pârvan 1926, p. 345.

- ^ Parvan 1926, p. 345.

- ^ Coles & Harding 1979, p. 366.

- ^ a b c d Gramatopol 1992, p. 1.

- ^ Sarbu & Florea 2000, p. 152.

- ^ a b Sanie 1995, p. 24.

- ^ a b Popescu 1956, p. 218.

- ^ Parvan 1926.

- ^ Sherratt 1984, p. 23 (picture at page 22.

- ^ Popescu 1950, p. 28.

- ^ Macrea 1978, p. 197.

- ^ Sîrbu 2004, p. 150.

- ^ a b Sanie 1995, p. 151.

- ^ Makkay 1995, p. 341.

- ^ Sîrbu 2004, p. 46 and p=47.

- ^ Sîrbu 2004, p. 47.

- ^ Burda 1979, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e f Florescu & Miclea 1979, p. 27.

- ^ Popescu 1941, p. 187.

- ^ a b Sîrbu 2004, p. 54.

- ^ a b Pârvan 1926, p. 540.

- ^ Sîrbu 2007, p. 864.

- ^ Daicoviciu 1971, p. 63.

- ^ a b Pârvan & 1926 546.

- ^ a b Pârvan 1926, p. 545.

- ^ a b Florescu & et. al 1980, p. 339.

- ^ Pârvan 1928, p. 58.

- ^ Henry 1928, p. 288.

- ^ a b c d e f g Popescu 1948, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e Parvan 1926, p. 542-543.

- ^ a b c d e Turcu 1979, p. 153.

- ^ a b c Szekely 1965, p. 57.

- ^ a b c Florescu & et. al. 1980, p. 68.

- ^ a b MacKenzie 1986, p. 87.

- ^ Berindei & Candea 2001, p. 749.

- ^ Sârbu 2007, p. 862.

- ^ a b Pârvan 1926, p. 550.

- ^ a b Spanu 2003, p. 11.

- ^ Parvan 1926, p. 542.

- ^ a b c Ortvay 1875, p. 216.

- ^ a b c Rustoiu 2002, p. 97.

- ^ a b c Rustoiu 2002, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Condraticova 2010, p. 117.

- ^ Condraticova 2010, p. 118.

- ^ Arnăut & Naniu 1996, p. 44.

- ^ a b Popović 2004, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Mărghitan 1979, p. 164.

- ^ a b Kolaric 1970, p. 22.

- ^ a b Popović 2004, p. 42.

- ^ a b Romer 1886, p. 391.

- ^ Plantos 2005, p. 77.

- ^ Plantos 2005, p. 78.

- ^ a b Plantos 2005, p. 79.

- ^ a b Spanu 2003, p. 12.

- ^ a b Popescu 1956, p. 244.

- ^ Florescu 1970, p. 135.

- ^ a b Oberländer-Târnoveanu & et.al. 2010, p. 9.

- ^ Seculici 2008, p. 69.

- ^ Popescu 1941, p. 197.

- ^ a b Popescu 1941, p. 188.

- ^ Rustoiu 1996, p. 47.

- ^ Parvan 1926, p. 532.

- ^ a b Spânu 1998, p. 49.

- ^ Crisan 1993, p. 45.

- ^ Oltean 2007, p. 106.

- ^ Florescu & Miclea 1979, p. 16.

- ^ Pârvan 1926, p. 534.

- ^ Packer & Sarring 1997, p. 377.

- ^ a b Pârvan 1928, p. 641.

- ^ a b Spanu & Cojocaru 2009, p. 99.

- ^ Popescu 1941, p. 198.

- ^ a b c Popescu 1941, p. 196.

- ^ Vauthey P & Vauthey M 1968, p. 346.

- ^ Bazarciuc 1983, p. 264.

- ^ Rustoiu 1996, p. 46.

- ^ Popescu 1941, p. 201.

- ^ Gorun & et. al. 1988, p. 116.

- ^ Toma 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Costea 2008, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Constantinescu 2009, p. 1031.

- ^ a b c Candea 2010, p. 52.

- ^ a b Florescu & Miclea 1979, p. 21.

- ^ Pârvan 1928, p. 548.

- ^ Oberländer-Târnoveanu 2011.

- ^ Pupaza 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Sanie 1995, p. 145.

- ^ a b c d Berciu 1974, p. 217.

- ^ Ispas 1980, p. 279.

- ^ Banateanu 1971, p. 38.

- ^ Shchukin 1989, p. 89.

- ^ Henry 1928, p. 290.

- ^ a b Popescu 1941, p. 193.

- ^ a b c d Pârvan 1928, p. 141.

- ^ a b Pupeză 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Pârvan 1928, p. 544.

- ^ Parvan 1926, p. 548.

- ^ Romer 1886, p. 390.

- ^ a b c Florescu & Miclea 1979, p. 22.

- ^ a b Hampel 1888, p. 278.

- ^ Florescu & Miclea 1979, p. 25.

- ^ Florescu & Miclea 1979, p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Florescu & Miclea 1979, p. 87.

- ^ Bichir 1984, p. 54.

- ^ Sârbu 2000, p. 170.

- ^ Sirbu 1997, p. 89.

- ^ Pârvan 1926, p. 641.

- ^ Pârvan 1926, p. 520.

- ^ Tutila 2004, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d Florescu & Miclea 1979, p. 26.

- ^ a b Berciu 1974, p. 210.

- ^ a b Sîrbu & Florea 2000, p. 169.

- ^ Mirea 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Mirea 2009, p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e Mirea 2009, p. 100.

- ^ a b Spânu & Cojocaru 2009, p. 111.

- ^ Arsenescu & Sirbu 2006, p. 170.

- ^ Crisan 1986, p. 26.

- ^ Sârbu 2007, p. 864.

- ^ Spânu 1998, p. 52.

- ^ Sârbu & Florea 1997, p. 32.

- ^ a b Spânu 1998, p. 46.

- ^ a b Gramatopol 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Spânu 1998, p. 47.

- ^ Florescu & Miclea 1979, p. 85.

- ^ Rustoiu 1996, p. 51.

- ^ Popescu 1971, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Watson 2011, p. 1.

- ^ Constantinescu 2007, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Constantinescu 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Trohani 2009, p. 1.

- ^ Constantinescu 2009, p. 1028.

- ^ a b c d Ciuta & Rustoiu 2007, p. 109.

- ^ Glodariu & et. al. 2008, p. 146.

- ^ Ciuta & Rustoiu 2007, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Ciuta & Rustoiu 2007, p. 110.

- ^ Constantinescu 2007, p. 11.

- ^ Ciuta & Rustoiu 2010, p. 110.

- ^ a b Constantinescu 2007, p. 26.

- ^ Constantinescu 2010, p. 1041.

- ^ Constantinescu 2010, p. 1038.

- ^ Depper-Lippitz 2008, p. 1.

References

- Arbunescu, Alexandru (2011). "Brăţară spiralică, tubulară cu protome de cai cu coarne (Tez. Cucuteni-Băiceni)". cIMeC; Muzeul Naţional de Istorie a României, București, Bunuri culturale mobile clasate în Patrimoniul Cultural Naţional 'Mobile Cultural Objects Classified in the National Cultural Heritage. http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=http%3A%2F%2Fclasate.cimec.ro%2Fdetaliu.asp%3Fk%3D34B70B9.

- Arnăut, Tudor; Naniu, Rodica Ursu (1996) (in Romanian). Vestigii getice din a doua epocă a fierului în interfluviul pruto-nistrean. Ed. Helios, Iasi. ISSN 9789739801133.

- Arsenescu, Margareta; Sirbu, Valeriu (2006). Dacian Settlements and Necropolis in Southwestern Romania (2nd century BC-1st century AD). V. ACTA TERRAE SEPTEMCASTRENSIS. pp. 163–188. ISSN 1583-1817.

- Banateanu, Tancred (1971). "Les Nagas dans les mythes populaires roumains pp.17–40" (in French). Mélanges de préhistoire d'archéocivilisation, et d'ethnologie offerts à André Varagnac. École Pratique des Hautes Études, VIe section. Centre de Recherches Historiques. http://books.google.ca/books?id=JdUDAAAAMAAJ&q.

- Bazarciuc, Violeta Veturia (1983). (Google books) "Cetatea Geto-Dacica de la Bunesti, Vaslui" (in Romanian). Studii și cercetări de istorie veche și arheologie: Volumes 34–35. Institutul de Arheologie. http://books.google.ca/books?id=IkppAAAAMAAJ&q (Google books).

- Berciu, Dumitru (1974) (in French). (Google books) Contribution à l'étude de l'art thraco gète. Editura Academiei, Romania. http://books.google.ca/books?id=DqDiAAAAMAAJ&q=Contribution+%C3%A0+l'%C3%A9tude+de+l'art+thraco+g%C3%A8te&dq=Contribution+%C3%A0+l'%C3%A9tude+de+l'art+thraco+g%C3%A8te&ei=To9AToevLZPYM5vdtOYC&cd=1 (Google books).

- Candea, Virgil (2001). (Google books) Istoria romanilor: Mostenirea timpurilor indepartate. Editura Enciclopedica, Bucuresti. ISBN 978-9734504312. http://books.google.ca/books?id=J2UsAQAAIAAJ&q=Istoria+romanilor:+Mostenirea+timpurilor+indepartate&dq=Istoria+romanilor:+Mostenirea+timpurilor+indepartate&hl=en&ei=2I9ATva_IMvdgQeNsci1Bw&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CDAQ6AEwAQ (Google books).

- Bichir, Gheorghe (1976). BAR supplementary series. British Archaeological Reports. http://books.google.ca/books?id=bCVmAAAAMAAJ&q.

- Bichir, Gheorghe (1984) (in Romanian). Geto-Dacii din Muntenia in epoca romana. Editura Academiei Romania. http://books.google.ca/books?id=B3geAAAAMAAJ&q.

- Burda, Stefan (1979) (in Romanian). Tezaure de aur din România. Editura Meridiane. http://books.google.ca/books?id=PJgrAAAAMAAJ&q.

- Candea, Virgil (2010) (in Romanian). MĂRTURII ROMÂNEŞTI PESTE HOTARE. Editura Biblioteca Bucureştilor. ISBN 978-973-8369-69-6.

- Childe, V. Gordon (1930). THE BRONZE AGE. Cambridge University Press, London. http://books.google.ca/books?id=Fxb9brYSPVYC&printsec.

- cIMeC, The Institute for Cultural Memory (2011). "Şimleu Silvaniei (denumire repertoriu: Şimleu Silvaniei sau Şimleul, Szilágysomlyó, jud. Sălaj) in 'ARCHAEOLOGICAL REPERTORY OF ROMANIA' Archive Of The 'Vasile Parvan' Institute Of Archaeology edited by Şandric Bogdan (Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/60Xzsl3kA)" (in Romanian). 'Vasile Parvan' Institute Of Archaeology. http://www.webcitation.org/60Xzsl3kA.