- Thraco-Roman

-

The terms Thraco-Roman and Daco-Roman refer to the culture and language of the Thracian and Dacian peoples who were incorporated into the Roman Empire and ultimately fell under the Roman and Latin sphere of influence.

Contents

Meaning and usage

The term was coined in 1901 by Ovid Densusianu,[1] who used it to describe the "oldest epoch of the creation of the Romanian language", when the Vulgar Latin spoken in the Balkans between the 4th and 6th centuries, having its own peculiarities,[2] had evolved into what is known as Proto-Romanian.[3] By extension, historians started to use the term to mean the time period of the history of the Romanian people until the 6th century, which witnessed the cultural and linguistic Romanisation of many Daco-Thracian tribes. The territory where this process took place, consensually agreed to be near the Jireček Line is characterized as having two main peculiarities:

- A Christian space, consisting both of an ancient, sedentary Christianity inherited from the Roman world and a newer Christianity that emerged through the conversion to Christianity of the rest of Daco-Thracian tribes. The Christian spirit shaped the civilization of the people, influencing the inclusion into the Roman (and East Roman) political and state structures.

- A space of Latin language, that emerged from the provincial horizon of Rome. It gave birth to the Romance language and the Roman name, as preserved in the memory of modern Romanians, Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians and Istro-Romanians.

The People

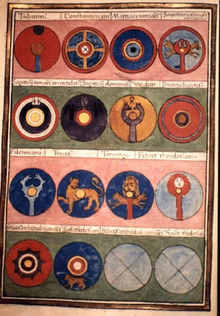

Page from the Notitia Dignitatum, a late Roman register of military commands, depicting shields of the magister militum praesentalis II. An analysis of East Roman army in 350-476 shows that the Danubian regions provided 54% of the total units. It is for this reason that Galerius "avowed himself the enemy of the Roman name and proposed that the empire should be called, not the Roman, but the Dacian empire".

Page from the Notitia Dignitatum, a late Roman register of military commands, depicting shields of the magister militum praesentalis II. An analysis of East Roman army in 350-476 shows that the Danubian regions provided 54% of the total units. It is for this reason that Galerius "avowed himself the enemy of the Roman name and proposed that the empire should be called, not the Roman, but the Dacian empire".

Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BC, is the first to describe the Getae as Thracian tribes. Several other sources from Antiquity claim the ethnic or linguistic identity of the two peoples. In his Geographia, Strabo again identifies the Getae as Thracians: “in the country of the Thracians and of those of their number who are Getae” and wrote about the two tribes (Dacians and Getae) as speaking the same language:[4] “the language of the Daci is the same as that of the Getae”. Justin considers the Dacians to be the successors of the Getae.[5] In his Roman history, Cassius Dio shows the Dacians to live on both sides of the Lower Danube. The ones south of the river (the area of Moesia, today's northern Bulgaria) called Moesians, while the ones north of the river are called Dacians. He argues that the Dacians are "either Getae or Thracians of Dacian race" (51.22)[6] but also stresses the fact that he calls the Dacians with the name used "by the natives themselves and also by the Romans" and that he is "not ignorant that some Greek writers refer to them as Getae, whether that is the right form or not" (67.6).[7]

In accordance with these testimonies some Romanian and Bulgarian scholars[8] developed hypotheses and theories arguing for common cultural, ethnical or linguistical features in the space north of Haemus mountains where both the populations of Dacians and of Getae were located. The linguist Ivan Duridanov identified a "Dacian linguistic area" [9] in Dacia, Scythia Minor, Lower Moesia and Upper Moesia. The archaeologist Mircea Babeş speaks of a "veritable ethno-cultural unity" between the Getae and the Dacians while the historian and archaeologist Alexandru Vulpe finds a remarkable uniformity of the Geto-Dacian culture.[10] There were also studies on Strabo's reliability and sources.[11] Some of these interpretation have echoed in other historiographies.[12]

The Romanian historian of ideas and historiographer Lucian Boia states: "At a certain point, the phrase Geto-Dacian was coined in the Romanian historiography to suggest a unity of Getae and Dacians".[13] Lucian Boia takes a skeptical position and argues the ancient writers distinguished among the two people, treating them as two distinct groups of the Thracian ethnos.[13][14] Boia contends that it would be naive to assume Strabo knew the Thracian dialects so well,[13] alleging that Strabo had "no competence in the field of Thracian dialects".[14] He also stresses that some Romanian authors cited Strabo indiscriminately.[14]

His position was supported by other scholars. The historian and archaeologist G. A. Niculescu also criticized the Romanian historiography and the archaeological interpretation, particularly on the "Geto-Dacian" culture.[15] Even those scholars whom consider Dacian, Getic and Thracian as distinct languages, agree about their descendence from an immediate common ancestor.

The occupied native population began to become more and more involved into the political life of the Empire. The tradition of Roman Emperors of Thracian origin dates back as early as the 3rd century. The first one was Regalianus, kinsman of the Dacian king Decebalus. By the 3rd century, the Thracians became an important part of the Roman army. The army used Latin as its operating language. This continued to be the case well after the 6th century, despite the fact that Greek was the common language of the Eastern empire.[16] This was not simply due to tradition, but also to the fact that about half the Eastern army continued to be recruited in the Latin-speaking Danubian regions of the Eastern empire. An analysis of known origins of comitatenses in the period 350-476 shows that in the Eastern army, the Danubian regions provided 54% of the total sample, despite constituting just 2 of the 7 eastern dioceses: Dacia and Thracia.[17] These regions continued to be the prime recruiting grounds for the East Roman army, e.g. the emperor Justin I (r. 518-27), father of Justinian I, a Latin-speaking Thracian[18][19][20][21][22] peasant from Bederiana (an unlocalized village in an area to this day inhabited by the Vlachs of Serbia), who bore, like his companions and members of his family (Zimarchus, Dityvistus, Boraides, Bigleniza, Sabatius, etc.) a Thracian name,[18][23] and who never learned to speak more than rudimentary Greek.

A number of Roman/East Roman emperors were Thraco-Romans: Regalianus, Galerius, Maximian, Maximinus Daia, Leo I, Aurelius Valerius Valens, Licinius, Constantine I the Great, Constantius III, Marcianus, Justin I, Justinian I, Justin II, Phocas.

The Roman name

Before 212, for the most part only inhabitants of the Italian peninsula (then a multi-ethnic region) held full Roman citizenship. Colonies of Romans established in other provinces, Romans (or their descendants) living in provinces, the inhabitants of various cities throughout the Empire, and small numbers of local nobles (such as client-kings) also held full citizenship. In contrast, the majority of provincials merely held limited Roman citizenship rights (if even that).

In 212, the Constitutio Antoniniana (Latin for "Constitution [or Edict] of Antoninus") was promulgated by the Roman Emperor Caracalla. The law declared that all free-born men of the Roman Empire were to be given full Roman citizenship and all free-born women of the Empire were given the same rights as Roman women. Caracalla passed this law mainly to increase the number of people available to tax and to serve in the legions (only full citizens could serve as legionaries in the Roman Army).

Caracalla's decree had thus effectively raised provincial populations to equal status with the city of Rome itself. The importance of this decree is historical rather than political. It set the basis for integration where the economic and judicial mechanisms of the state could be applied in all provinces, as it had been expanded earlier from Latium to all of Italy. Of course, integration did not take place uniformly. Societies already integrated within the Empire and situated in a central geographic position, such as Dacia, Moesia, Greece, etc., were favored by this decree, compared with those far away, too poor or just too alien such as Britain, Palestine or Egypt.

If, for the first centuries after the Roman conquest of Dacia, the antagonism between the occupied and free Dacian tribes and the Romans was clearly visible, as demonstrated by the episode when Emperor Galerius claimed that the name of the Empire should be changed into the "Dacian Empire"[24], the new law providing Roman citizenship to all Roman subjects was an important factor for complete political and cultural integration into the Roman world, having, as one of its most important results, the adoption of the Roman name as autonym, with its later dialectical variants, either Român, Rumân, Aromân, Rumân or Rëmëri. The last clear anti-Roman stances are from the 4th century, when Constantine the Great defeated the Dacians, assuming the title Dacicus Maximus in 336, and the last Carpian attack in the 5th century.

The Dark Ages

In the 6th century, the Thraco-Roman populations witnessed the invasion of the Avars. Under the dominion of the Avars, the Slavs made their appearance.

From this time, the area experienced a state of cultural regression with the population becoming strongly rural, concentrating on agriculture and animal husbandry, but having thus the opportunity to preserve the unity of the language. The future would see the detachment of a part of this Romance speaking population, called Vlachs, from the main body of this Danubian Romanity, as a result of the historical circumstances created by the Slavic and Bulgar invasions. Although scattered throughout the Peninsula and reduced to more modest, rural life forms, this population preserved its ethnic identity and habits and continued to speak the same language.

The Empire's loss of territory was offset to a degree by consolidation and an increased uniformity of rule. Emperor Heraclius made Greek the official language during his reign, isolating the Latin-speaking populations of the Balkans. Despite its survival in the army and in legal and administrative terms, the use of Latin gradually declined.

Although some Byzantine control remained in cities along the southern coasts, all of the northern and central Balkans were virtually overrun by the Slavs. Nonetheless, in the isolated and ignored lands north of the Danube, the Slavs were gradually absorbed and Romanized, and the Latin character of the language was preserved. The influence of the Slavs was greater on the right bank of the Danube, where attracted by the rich urban areas to the south, overwhelmed the native population by weight of numbers in Dalmatia, Macedonia, Thrace, Moesia and Greece, turning those provinces into so-called “Sklavinias”. The impact of the arrival of the Bulgars in the 7th century, and the sequential establishment in the 9th century of a powerful state, was particularly great, having caused the end of the division of the Romanic population of the Balkan Peninsula started by the Avar-Slavic invasions. This process split the population into two sections: one found shelter in the north and its thick forests (80% of the territory), while the other moved southwards to the valleys of the Pindus and of the Balkan Mountains, causing an "ebb and tide" phenomenon of the native populations.[25]

Christianity

Early history

The Biertan Donarium - an early Christian votive object of early 4th century, unearthed at Biertan, near Sibiu, in Romania

It reads EGO ZENOVIUS VOTUM POSUI

"I, Zenovius, offered this gift"Christianity began gradually to spread as early as late antiquity, moving toward one of the northern borders of the “classical” world, thus making the Carpathian and Danubian territories part of a chain whereby Rome, its provinces, and the missionaries of the Eastern Church preached the word of the new faith from Iberia to the Caucasus.

Christianity was brought to the area by the occupying Romans. The Roman province had traces of all imperial religions, including Mithraism, but Christianity, a religio illicita, existed among some of the Romans.

The earliest evidence of Christianity is a grave inscription from the 2nd century, found in Napoca, bearing the formula Sit tibi terra levis ("Să-ţi fie ţărâna uşoară" in Romanian).[26] The inscription was made by a "college" (a trading association) whose members originated from the Middle East. Among the other persons mentioned in the inscription, most of them bear Roman names, suggesting that Christianity had spread among the ranks of the soldiers as early as the 2nd century AD.

When the Romanians formed as a people, it is clear that they already had the Christian faith, as proved by archeological and linguistic evidence. Basic terms of Christianity are of Latin origin: such as church ("biserică" < basilica), God ("Dumnezeu" < Domine Deus), Easter ("Paşte" < Paschae), Pagan ("Păgân" < Paganus), Angel ("Înger" < Angelus), Cross ("Cruce" < Crux). Some of them, especially "Church" - Biserica are unique to Romanian Orthodoxy.

After Christianity became the official religion, the first bishoprics were created in the area, of which the main archbishoprics were at Singidunum (Belgrade), Viminacium (now Kostolač), Ratiaria (now Arčar, near Vidin), Marcianopolis (now Devnya), and Tomis (now Constanţa).[26]

Very few traces can be found in the Romanian names that are left from the Roman Christianity after the Slavic influence began. All the names of the saints were preserved in Latin form: "Sântămăria" (Mary), "Sâmpietru" (Saint Peter), "Sângiordz" (Saint George) and "Sânmedru" (Saint Demetrius). The non-religious onomastic proof of pre-Christian customs, like "Sânziana" and "Cosânzeana" (Sancta Diana and Qua Sancta Diana) is only of anecdotal value in this context[citation needed]. Yet, the highly spiritualized places in the mountains, the processions, the calendars, and even the physical locations of the early churches were clearly the same with those of the Dacians[citation needed]. Even Saint Andrew is known locally as the Apostle "of the wolves" - with very old and large connotations, whereby the wolf's head was an ethnicon and a symbol of military and spiritual "fire" for Dacians.[citation needed]

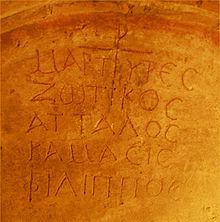

Tomb of the Four Martyrs - Niculiţel, Romania

Tomb of the Four Martyrs - Niculiţel, Romania

Christianity in Scythia Minor

While Dacia was part of the Roman Empire only for a short time, Scythia Minor (nowadays Dobrogea) was part of it much longer and after the breakdown of the Roman Empire, it became part of the Byzantine Empire.

The first legendary encounter of Christianity in Scythia Minor was when Saint Andrew, brother of Saint Peter passed through it in the 1st century with his disciples. Later on, Christianity became the predominant faith of the region, as proven by the large number of remains of early Christian churches. The Roman administration was ruthless with the Christians, as the great number of martyrs demonstrates.

Bishop Ephrem, killed on 7 March 304 in Tomis, was the first Christian martyr of this region and was followed by countless others, especially during the repression ordered by emperors Diocletian, Galerius, Licinius and Julian the Apostate.

An impressive number of dioceses and martyrs are first attested during the times of Ante-Nicene Fathers. The first known Daco-Roman Christian priest Montanus and his wife Maxima were drowned, as martyrs, because of their faith, on March 26, 304.

The 1971 archaeological digs under the paleo-Christian basilica in Niculiţel (near ancient Noviodunum in Scythia Minor) unearthed an even older martyrium. Besides Zoticos, Attalos, Kamasis and Filippos, who suffered martyrdom under Diocletian (304-305), the relics of two previous martyrs, witnessing and dying during the repressions of Emperor Decius (249-251), were unearthed under the crypt.

The names of these martyrs had been placed since their death in church records, and the find of the tomb with the names written inside was astonishing. The fact that the relics of the famous Saint Sava "the Goth" (martyred by drowning in the River Buzău, under Athanaric on 12 April 372) were recovered by Saint Basil the Great conclusively demonstrates that (unlike bishop Wulfila) Saint Sava was a follower of the Nicene faith, not a heresiarch like Arius.

Once the Dacian-born Emperor Galerius proclaimed freedom for Christians all over the Roman Empire in 311,[27] the city of Tomis alone (modern Constanţa) became Metropolitanate with as many as 14 bishoprics.

By the 4th century, a powerful and organised nucleus of Christian monks existed in the area, known as the Scythian monks.

Language

The Roman occupation led to a Roman-Thracian syncretism, and similar to the case of other conquered civilisation (see Gallo-Roman culture developed in Roman Gaul), had as final result the Latinization of many Thracian tribes which were on the edge of the sphere of Latin influence, eventually resulting in the possible extinction of the Daco-Thracian language (unless, of course, Albanian is its descendant), although traces of it are still preserved in the Eastern Romance substratum. Starting from the 2nd century AD, the Latin spoken in the Danubian provinces starts to display its own distinctive features, separate from the rest of the Romance languages, including those of western Balkans (Dalmatian).[28] The Thraco-Roman period of the Romanian language is usually delimited between the 2nd (or earlier, via cultural influence and economic ties) and the 6th or 7th century.[29] It is divided, in turn, into two periods, with the division falling roughly in the 3rd-4th century. The Romanian Academy considers the 5th century as the latest date when the differences between Balkan Latin and western Latin could have appeared,[30] and that between the 5th and 8th centuries, this new language – Romanian - switched from Latin speech, to a neolatine vernacular idiom, called Proto-Romanian.[31][32]

First sample of Romanian language

Referring to this time period, of great debate and interest is the so called "Torna, Torna Fratre" episode. In Theophylactus Simocatta Histories, (c. 630), the author mentions the words "τóρνα, τóρνα". The context of this mention is a Byzantine expedition during Maurice's Balkan campaigns in the year 587, led by general Comentiolus, in the Haemus Mons, against the Avars. The success of the campaign was compromised by an incident: during a night march...

-

- "a beast of burden had shucked off his load. It happened as his master was marching in front of him. But the ones who were coming from behind and saw the animal dragging his burden after him, had shouted to the master to turn around and straighten the burden. Well, this event was the reason for a great agitation in the army, and started a flight to the rear, because the shout was known to the crowd: the same words were also a signal, and it seemed to mean “run”, as if the enemies had appeared nearby more rapidly than could be imagined. There was a great turmoil in the host, and a lot of noise; all were shouting loudly and goading each other to turn back, calling with great unrest in the language of the country "torna, torna", as a battle had suddenly started in the middle of the night."[33]

Nearly two centuries after Theophylactus, the same episode is retold by another Byzantine chronicler, Theophanes Confessor, in his Chronographia (c. 810–814). He mentions the words: "τόρνα, τόρνα, φράτρε" [torna, torna fratre]:

-

- "A beast of burden had thrown off his load, and somebody yelled to his master to reset it, saying in the language of their parents/of the land: "torna, torna, fratre". The master of the animal didn't hear the shout, but the people heard him, and believing that they are attacked by the enemy, started running, shouting loudly: "torna, torna"".[34]

The first to identify the excerpts as examples of early Romanian was Johann Thunmann in 1774.[35] Since then, a debate among scholars had been going on to identify whether the language in question is a sample of early Romanian,[36] or just a Byzantine command [37] (of Latin origin, as it appears as such–torna–in Emperors Mauricius Strategikon), and with “fratre” used as a colloquial form of address between the Byzantine soldiers.[38] The main debate revolved around the expressions πιχώριoς γλσσα (epihorios glossa - Theopylactus) and πάτριoς φωνή (patrios fonē - Theophanes), and what they actually meant.

An important contribution to the debate was Nicolae Iorga's first noticing in 1905 of the duality of the term torna in Theophylactus text: the shouting to get the attention of the master of the animal (in the language of the country), and the misunderstanding of this by the bulk of the army as a military command (due to the resemblance with the Latin military command).[39] Iorga considers the army to have been composed of both auxiliary (τολδον) Romanised Thracians—speaking πιχωρί τε γλώττ (the “language of the country” /”language of their parents/of the natives”) —and of Byzantines (a mélange of ethnicities using Byzantine words of Latin origin as official command terms, as attested in the Strategikon).[40]

This view was later supported by the Greek historian A. Keramopoulos (1939),[41] as well as by Al. Philippide (1925), who considered that the word torna should not be understood a solely military command term, because it was, as supported by chronicles, a word “of the country”,[42] as by the year 600, the bulk of the Byzantine army was raised from barbarian mercenaries and the Romanic population of the Balkan Peninsula.[43]

Starting from the second half of the 20th century, the general view is that it is a sample of early Romanian language, a view with supporters such as Al. Rosetti (1960),[44] Petre Ş. Năsturel (1956)[45] and I. Glodariu (1964).[46]

See also

- History of Romania

- Age of Migrations

- Gallo-Roman

- Culture of Ancient Rome

- Dacian language

- Thracian language

- Eastern Romance substratum

- Romanian language

- Origin of the Romanians

- Romance languages

- Legacy of the Roman Empire

- The Balkan linguistic union

Further reading

Online:

- (Romanian) Sorin Olteanu, The administrative organisation of the Balkan provinces in the 6th century AD

- (English) Stelian Brezeanu: Toponymy and ethnic Realities at the Lower Danube in the 10th Century. “The deserted Cities" in Constantine Porphyrogenitus' De administrando imperio

- (English) Kelley L. Ross The Vlach Connection and Further Reflections on Roman History

Notes

- ^ Ovide Densusianu, Histoire de la langue roumaine, I, Paris, 1901. DLR 1983.

- ^ Ovid Densusianu: "Nu există nici o îndoială că romanica din Peninsula Balcanică a prezentat încă din primele secole ale erei noastre câteva trăsături caracteristice." ("There is no doubt that the Romanic of the Balkan peninsula in the first centuries of our era already presented some characteristic traits.")

- ^ Ovid Densusianu, 1901: "latina vulgară şi-a pierdut unitatea, fărâmiţându-se în limbile ce aveau să devină limbile romanice de astăzi." ("Vulgar Latin had lost its unity, breaking into languages that developed into today's Romance languages."

- ^ LacusCurtius • Strabo's Geography — Book VII Chapter 3

- ^ Justin, Epitome of Pompeius Trogus: "Daci quoque suboles Getarum sunt" (The Dacians as well are a scion of the Getae)

- ^ Cassius Dio — Book 51

- ^ Cassius Dio — Epitome of Book 67

- ^ Giurescu, Constantin C. (1973) (in Romanian). Formarea poporului român. Craiova. p. 23.: "They (Dacians and Getae) are two names for the same people [...] divided in a large number of tribes". See also the hypothesis of a Daco-Moesian language / dialectal area supported by linguists like Ivan Duridanov and Sorin Olteanu.

- ^ Duridanov, Ivan. "The Thracian, Dacian and Paeonian languages". http://www.kroraina.com/thrac_lang/thrac_8.html. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ Petrescu-Dîmboviţa, Mircea; Vulpe, Alexandru (eds), ed (2001) (in Romanian). Istoria Românilor, vol. I. Bucharest. It should be noted Al. Vulpe speaks of Geto-Dacians as a conventional and instrumental concept for the Thracian tribes inhabiting this space, but not meaning an "absolute ethnic, linguistic or historical unity".

- ^ Janakieva, Svetlana (2002). "La notion de ΟΜΟΓΛΩΤΤΟΙ chez Strabon et la situation ethno-linguistique sur les territoires thraces" (in French). Études Balkaniques (4): 75–79. The author concludes Strabo's claim sums an experience following of many centuries of neighbourhood and cultural interferences between the Greeks and the Thracian tribes

- ^ The Cambridge Ancient History vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. 1982. In chapter "20c Linguistic problems of the Balkan area", at page 838, Ronald Arthur Crossland argues "it may be the distinction made by Greeks and Romans between the Getae and Daci, for example, reflected the importance of different sections of a linguistically homogenous people at different times". He furthermore recalls Strabo's testimony and Georgiev's hypothesis for a 'Thraco-Dacian' language.

- ^ a b c Boia, Lucian (2004). Romania: Borderland of Europe. Reaktion Books. p. 43. ISBN 1-86189-103-2.

- ^ a b c Boia, Lucian (2001). History and Myth in Romanian Consciousness. Central European University Press. p. 14. ISBN 9639116971.

- ^ Niculescu, Gheorghe Alexandru (2004–2005). "Archaeology, Nationalism and "The History of the Romanians" (2001)". Dacia - Revue d'archéologie et d'histoire ancienne (48–49): 99–124. He dedicates a large part of his assessment to the archaeology of "Geto-Dacians" and he concludes that with few exceptions "the archaeological interpretations [...] are following G. Kossinna's concepts of culture, archaeology and ethnicity".

- ^ Maurice Strategikon

- ^ Elton (1996) 134

- ^ a b Ion I. Russu, Elementele traco-getice în Imperiul Roman și în Byzantium (veacurile III-VII), Editura Academiei R. S. România, 1976, pag.95

- ^ Velizar Iv Velkov, Cities in Thrace and Dacia in Late Antiquity: (studies and Materials), University of Michigan, 1977, pag.47

- ^ Robert Browning, Justinian and Theodora, Gorgias Press LLC, 2003, ISBN 1-59333-053-7, pag.23

- ^ Scott Fitzgerald Johnson, Greek Literature in Late Antiquity, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd, 2006, ISBN 0-7546-5683-7, pag.166

- ^ John Julius Norwich, A Short History of Byzantium, Vintage Books, 1997, ISBN 0-679-77269-3, pag.59

- ^ James Allan Stewart Evans, The Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial Power, Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-23726-2, pag. 96

- ^ Lactanius, "Of the manner in which the persecutors died"[1]: "Whatever, by the laws of war, conquerors had done to the conquered, the like did this man presume to perpetrate against Romans and the subjects of Rome, because his forefathers had been made liable to a like tax imposed by the victorious Trajan, as a penalty on the Dacians for their frequent rebellions." [...] "Long ago, indeed, and at the very time of his obtaining sovereign power, he had avowed himself the enemy of the Roman name; and he proposed that the empire should be called, not the Roman, but the Dacian empire."

- ^ Matyla Ghyka: A documented chronology of Roumanian history

- ^ a b Petre P. Panaitescu, Istoria Românilor ("History of the Romanians"), Bucharest, 1942

- ^ See Galerius and Constantines edicts of Toleration from 311 and 313, at Medieval Sourcebook

- ^ Al. Rosetti: "Istoria limbii române" ("History of the Romanian Language"), Bucharest, 1986

- ^ Dicţionarul limbii române (DLR), serie nouă ("Dictionary of the Romanian Language, new series"), Academia Română, responsible editors: Iorgu Iordan, Alexandru Graur, Ion Coteanu, Bucharest, 1983;

- ^ “Istoria limbii române” ("History of the Romanian Language"), II, Academia Română, Bucharest, 1969;

- ^ I. Fischer, "Latina dunăreană" ("Danubian Latin"), Bucharest, 1985.

- ^ A. B. Černjak "Vizantijskie svidetel'stva o romanskom (romanizirovannom) naselenii Balkan V–VII vv; “Vizantinskij vremmenik", LIII, Moscova, 1992

- ^ Theophylacti Simocattae Historiae, II, 15, 6–9, ed. De Boor, Leipzig, 1887; cf. FHDR 1970

- ^ Theophanis Chronographia, I, Anno 6079 (587), 14–19, ed. De Boor, Leipzig, 1883; cf. FHDR 1970: 604.

- ^ Johann Thunmann: “Untersuchungen über die Geschichte der östlichen europäischen Völker” ("Investigations into the histories of eastern European peoples"), 1. Theil, Leipzig, 1774, p. 169–366.: "Gegen das Ende des sechsten Jahrhunderts sprach man schon in Thracien Wlachisch" ("Towards the end of the sixth century, someone already spoke in Tracian Vlachish")

- ^ This view, which suggested that the expression should be taken as such: the language of the country and the language of their fathers/of the natives, thus being a sample of Romanian was supported by historians and philologists such as F. J. Sulzer in “Geschichte des transalpinischen Daciens” ("History of the Transalpine Dacians"), II, Vienna, 1781; G. Şincai in “Hronica românilor şi a mai multor neamuri” ("Chronicle of the Romanians and of many more peoples", I, Iaşi, 1853; C.Tagliavini in ”Le origini delle lingue neolatine” ("The origins of the Neo-Latin languages"), Bologna, 1952; W. Tomaschek in “Über Brumalia und Rosalia” ("Of Brumalia and Rosalia", Sitzungsberichte der Wiener Akademie der Wissenschaften, LX, Viena, 1869; R. Roesler in “Romänische Studien” ("Romanian Studies"), Leipzig, 1871; Al. Rosetti in “Istoria limbii române” ("History of the Romanian Language", Bucharest, 1986; D. Russo in “Elenismul în România” ("Hellenism in Romania"), Bucharest, 1912.; B. P. Hasdeu in “Strat şi substrat. Genealogia popoarelor balcanice” ("Stratum and Substratum: Genealogy of the Balkan Peoples"), Analele Academiei Române, Memoriile secţiunii literare, XIV, Bucharest, 1892; A. D. Xenopol in “Une énigme historique. Les Roumains au Moyen Âge” ("An historic enigma: the Romanians of the Middle Ages"), Paris, 1885 and “Istoria românilor” ("History of the Romanians"), I, Iaşi, 1888; H. Zilliacus in “Zum Kampf der Weltsprachen im oströmischen Reich” ("To the struggle of world languages in the Eastern Roman Empire"), Helsinki, 1935; R. Vulpe in “Histoire ancienne de la Dobroudja” ("Ancient history of Dobrugea"), Bucharest, 1938; C. Popa-Lisseanu in “Limba română în izvoarele istorice medievale” ("The Romanian language in the sources of medieval history"), Analele Academiei Române. Memoriile secţiunii literare, 3rd series, IX, 1940. Lot 1946; G. I. Brătianu in “Une énigme et un miracle historique: le peuple roumain” ("An enigma and an historic miracle: the Romanian people"), Bucharest, 1942; etc.

- ^ This view had proponents such as J. L. Pić in “Über die Abstammung den Rumänen” ("On the descent of the Romanians"), Leipzig, 1880; J. Jung in “Die romanischen Landschaften des römischen Reiches” ("Romanian landscapes of the Roman Empire") , Innsbruck, 1881; A. Budinszky in “Die Ausbreitung der lateinischen Sprache über Italien und Provinzen des Römischen Reiches” ("The propagation of the Latin language in Italy and the provinces of the Roman Empire"), Berlin, 1881; D. Onciul: “Teoria lui Roesler” ("Rosler's Theory") in “Convorbiri literare”, XIX, Bucharest, 1885; C. Jireček in “Geschichte der Bulgaren” ("History of the Bulgarians"), Prague, 1876; Ovide Densusianu: “Histoire de la langue roumaine” ("History of the Romanian language"), I, Paris, 1901; P. Mutafčief: “Bulgares et Roumains dans l'histoire des pays danubiens” ("Bulgarians and Romanians in the history of the Danubian lands"), Sofia, 1932; F. Lot: “La langue de commandement dans les armées romaines et le cri de guerre français au Moyen Âge” ("The language of command in the Romanian armies and the French war cry in the Middle Ages") in volume “Mémoires dédiés à la mémoire de Félix Grat” ("Memoirs dedicated to the memory of Félix Grat"), I, Paris, 1946;

- ^ Idea supported by Franz Dölger in “Die „Familie” der Könige im Mittelalter” ("The 'family' of the king in the Middle Ages"), „Historisches Jahrbuch” ("Historical Yearbook"), 1940, p. 397–420; and M. Gyóni in “Az állitólagos legrégibb román nyelvemlék (= "Das angeblich älteste rumänische Sprachdenkmal", "The allegedly oldest spoken evidence of the Romanian language")”, „Egyetemes Philologiai Közlöny (Archivum Philologicum)”, LXVI, 1942, p. 1–11

- ^ Nicolae Iorga, Istoria românilor ("History of the Romanians"), II, Bucharest, 1936, p. 249.

- ^ “Într-o regiune foarte aproape de Haemus, unde se găsesc nume romanice precum Kalvumuntis (calvos montes), unul dintre soldaţii retraşi din cel mai apropiat ţinut primejduit strigă «în limba locului» ( πιχωρί τε γλώττ ) unui camarad care-şi pierduse bagajul «retorna» sau «torna, fratre»; datorită asemănării cu unul din termenii latineşti obişnuiţi de comandă, strigătul e înţeles greşit şi oastea, de teama unui duşman ivit pe neaşteptate, se risipeşte prin văi”. ("In a region very close to Haemus, where one finds Romanic names such as Kalvumuntis (calvos montes), one of the soldiers retreated from the nearest endangered land shouts «in the local language« (πιχωρί τε γλώττ) to a comrade who had lost his baggage retorna or torna, fratre ("turn back" or "turn, brother"); given the similarity to one of the customary Latin terms of command, the shout is understood heavily (?) and the host, fearing that an enemy had unexpectedly appeared, disperses through the haze." Nicolae Iorga, Istoria românilor ("History of the Romanians"), II, Bucharest, 1936.

- ^ A. Keramopoullos (A. Κεραµóπουλλου): “Τ ε ναι ο Kουτσóβλαχ” ("Who are the Aromanians"), Athens, 1939: “moreover, the term fratre, betraying the familiarity of the comrades, dismissed the possibility of a military term”

- ^ Al. Philippide, Originea românilor ("Origin of the Romanians"), I, Iaşi, 1925: „Armata, dacă a înţeles rău cuvântul torna, ca şi cum ar fi fost vorba că trebuie să se întoarcă cineva să fugă, l-a înţeles ca un cuvânt din limba ţării, din limba locului, căci doar Theophylactos spune lămurit că «toţi strigau cât îi ţinea gura şi se îndemnau unul pe altul să se întoarcă, răcnind cu mare tulburare în limba ţării: retorna»” ("The army, if it understood badly the word torna, which also could have been the word that turned back someone who ran away, understood it as a word of the language of the country, of the language of the place, because only Theophylactos says clearly that 'everyone shouted it from mouth to mouth the gave one another the impetus to turn around, yelling with great concern in the language of the country: turn back'")

- ^ „Dar se pare că Jireček n-a cetit pagina întreagă a descripţiei din Theophylactos şi Theophanes. Acolo se vede lămurit că n-avem a face cu un termin de comandă, căci un soldat s-a adresat unui camarad al său cu vorbele retorna ori torna, torna, fratre, pentru a-l face atent asupra faptului că s-a deranjat sarcina de pe spatele unui animal” ("But it seems that Jireček hadn't read the whole page of description by Theophylactos and Theophanes." There one sees clearly that they it wasn't made as a term of command, because a soldier addressed a comrade of his with the words "turn back" or "turn, turn, brother" to draw his attention to the fact that the burden was disturbed on the back of an animal") […] “Grosul armatelor bizantine era format din barbari mercenari şi din populaţia romanică a Peninsulei Balcanice” ("The bulk of the Byzantine army was formed of mercenary barbarians and of the Romanic population of the Balkan Peninsula") […] „armata despre care se vorbeşte în aceste pasaje [din Theophylactus şi Theophanes] opera în părţile de răsărit ale muntelui Haemus pe teritoriu thrac romanizat” ("The army about which they are speaking in these passages [of Theophylactus and Theophanes] was raised in part in the Haemus mountains in the Romanized Thracian territory.")[…] „Ca să ne rezumăm părerea, cuvântul spus catârgiului era un termen viu, din graiul însoţitorilor lui, sunând aproape la fel cu cuvântul torna din terminologia de comandă a armatei bizantine” ("To sum up the opinion, the word spoken catârgiului (? - word somehow related to catâr = "mule") was a live term, from the dialect [here and below, we render grai as "dialect"; the term falls between "accent" and "dialect" - ed.] of their guide, being almost the same as the word torna from the terminology of command of the Byzantine army.") „nimic nu este mai natural decât a conchide, cum au făcut toţi înainte de Jireček, că vorbele torna, retorna, fratre sunt cuvinte româneşti din veacul al şaselea” ("Nothing is more natural than to conclude, as did everyone since Jireček, that the words torna, retorna, fratre are Romanian words from the 6th century.") […] „Preciziunea povestirii lui Teofilact nu a fost până acum luată în seamă aşa cum trebuie. Totuşi reiese clar din aceste rânduri: 1) că cuvântul întrebuinţat de însoţitorii stăpânului catârului nu era chiar acelaşi cu cuvântul pe care oştenii şi-au închipuit că-l aud şi 2) că, pe când în gura tovarăşilor lui cuvântul însemna doar «întoarce-te», ε ς τo πίσω τραπέσθαι, aşa cum susţin cu bună dreptate mai toţi cercetătorii români, în schimb cuvântul aşa cum l-au înţeles ostaşii însemna «înapoi, la stânga împrejur», precum şi-au dat seama tot cu bună dreptate Jireček şi alţi învăţaţi, fiind, prin urmare, după chiar mărturia Strategikon-ului aşa-zis al împăratului Mauriciu, un cuvânt din graiul oştirilor bizantine” ("The precision of Theophylactus' story has still not been given the account it deserves. Everything follows clearly from these lines: 1) that the word employed the guides of the master of the mules was not even the same as the word the soldiers thought they heard and 2) that, although in the mouth of their comrade the word meant merely "turn around, ε ς τo πίσω τραπέσθαι, just as all the Romanian researchers still sustain, instead the word as understood by the soldeirs meant "turn back, left about!", according to what Jireček and other scholars have correctly understood, being, through its consequences, after even the witness of the Strategikon so in this manner by the emperor Maurice, a word in the dialect of the Byzantine army.")

- ^ Al. Rosetti, “Despre torna, torna, fratre” ("About torna, torna, fratre"), Bucharest, 1960, p. 467–468.: „Aşadar, termenii de mai sus aparţineau limbii populaţiei romanizate, adică limbii române în devenire, după cum au susţinut mai demult unii cercetători şi, printre ei, A. Philippide, care a dat traducerea românească a pasajelor respective, însoţită de un comentariu convingător. Termenii coincid cu termenii omonimi sau foarte apropiaţi din limba latină, şi de aceea ei au provocat panică în împrejurarea amintită.” ("Thus, the terms from above belong to the language of the romanized population, that is, the Romanian language in the process of development, as has long been sustained by some scholars and, among them, A. Philippide, who gave the Romanian translation to the respective passages, guided by a convincing commentary. The terms coincide with homonymic terms or very close from the Latin language, and from that caused panic in those nearby who heard it.")

- ^ Petre Ş. Năsturel, “Quelques mots de plus à propos de «torna, torna» de Théophylacte et de «torna, torna, fratre» de Théophane” ("Those words more appropriate than Theophylactus' torna, torna and Theophanus' torna, torna, fratre"), in Byzantinobulgarica, II, Sofia, 1966: Petre Ş. Năsturel “Torna, torna, fratre. O problemă de istorie şi de lingvistică” ("Torna, torna, fratre: a problem in the history of linguistics") in Studii de cercetări şi istorie veche, VII, Bucharest, 1956: “era un cuvânt viu din graiul populaţiei romanice răsăritene şi poate fi socotit ca cea mai veche urmă de limbă străromână; la fel ca şi φράτρε ['fratre']. Dar tot atunci se păstra în armata bizantină acelaşi cuvânt cu înţelesul de «înapoi», «stânga împrejur», ceea ce a amăgit pe oştenii lui Comentiolus, punându-i pe fugă” ("was a live word in the Eastern Romanic population and could have been reckoned as the oldest utterance of the Old Romanian language; the same also for φράτρε ['fratre']. But still, the Byzantine army retained this word with the sense of "turn back", "left about", as had deluded the soldiers of Comentiolus, putting them to flight") […] “făceau parte din aşa-zisul το⋅λδον, care cuprindea samarele, slugile şi vitele de povară. Măcar ei erau băştinaşi, în sensul larg al cuvântului [...]; ei făceau parte din latinitatea răsăriteană din veacul al VI-lea” ("made up part of the so-called το⋅λδον ['the auxiliary troops'], which includes pack-saddles, servants and draft cattle. Even those were natives, in the broad sense of the word [...]; they formed part of the Eastern Latinity of the 6th century") […] “Reieşe din aceasta în chip limpede şi cu totul neîndoielnic că cel puţin pentru catârgiu şi pentru tovarăşii lui vorba torna era un cuvânt din graiul lor – la fel cu siguranţă şi φράτρε – pe când la urechile şi în gura oştenilor apărea, cum dovedeşte Strategikon-ul, ca un cuvânt ostăşesc de poruncă. [...]. Cu alte cuvinte, chiar dacă oastea nu a fost alcătuită din băştinaşi, se aflau împreună cu ea oameni care vorbeau o limbă romanică” ("The result of this clearly and without the least doubt, is that for the muleteer and for his comrades, the word torna was a word in their own dialect – as certainly was φράτρε ['fratre'] – which when it appeared in the ears and mouths of the soldiers, as the Strategikon proves, was a was a soldiers word of command. [...]. In other words, even if the army had not been made up of natives, it would turn out that those men spoke a Romanic language") […]„torna era un cuvânt din graiul lor” ("torna was a word of their dialect".)

- ^ I. Glodariu: “În legatura cu «torna, torna, fratre»” in „Acta Musei Napocensis”, I, Cluj, 1964: „din oameni care transportau bagajele armatei, rechiziţionaţi cu acest scop şi, în sens[ul] larg al cuvântului, erau localnici” ("among the men who transported the army's baggage, requisitioned with such a scope and, in the broad sense of the word, they were locals") […] „torna era un cuvânt din graiul viu al populaţiei băştinaşe” ("torna was a word in the live dialect of the local population") […] “e cert că cei din jur l-au interpretat ca «întoarce-te», dacă nu erau soldaţi (şi termenul folosit de Theophanes ne face să credem că nu erau), sau ca «stânga-mprejur», dacă erau ostaşi” ("It is certain the those nearby interpreted it as "turn around", if they weren't soldiers (and the term used by Theophanes does not make us believe they were), or as "left about!", if they were soldiers")[…] „exista o verigă sigură între lat. frater şi rom. frate” ("there is a sure link between Latin frater and Romanian frate").

References

- Nicolae Saramandru: “Torna, Torna Fratre”; Bucharest, 2001–2002; Online: .pdf.

- Nicolae-Şerban Tanaşoca: “«Torna, torna, fratre» et la romanité balkanique au VI e siècle” ("Torna, torna, fratre, and Balkan Romanity in the 6th century") Revue roumaine de linguistique, XXXVIII, Bucharest, 1993.

- Nicolae Iorga: “Geschichte des rumänischen Volkes im Rahmen seiner Staatsbildungen” ("History of the Romanian people in the context of its statal formation"), I, Gotha, 1905; “Istoria românilor” ("History of the Romanians"), II, Bucharest, 1936. Istoria României ("History of Romania"), I, Bucharest, 1960.

- Elton, Hugh (1996). Warfare in Roman Europe, AD 350-425. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198152415.

Categories:- Ancient Roman culture

- Romanization of Southeastern Europe

- Eastern Romance people

- History of the Romanian language

- History of religion in Moldova

- History of religion in Romania

- Dacia

- Roman Dacia

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.