- Dr. Strangelove

-

For other uses, see Strangelove (disambiguation).

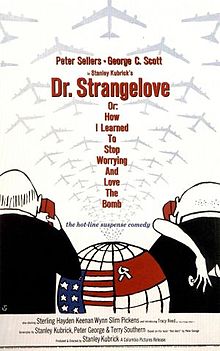

Dr. Strangelove or:

How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb

Original film poster by Tomi UngererDirected by Stanley Kubrick Produced by Stanley Kubrick Written by Stanley Kubrick

Peter George

Terry Southern

Uncredited:

Peter Sellers

James B. HarrisBased on Red Alert by

Peter GeorgeStarring Peter Sellers

George C. Scott

Sterling Hayden

Keenan Wynn

Slim PickensMusic by Laurie Johnson Cinematography Gilbert Taylor Editing by Anthony Harvey Studio Hawk Films Distributed by Columbia Pictures Release date(s) January 29, 1964 Running time 90 minutes Language English Budget US$1.8 million Box office $9,164,370 (US) Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, commonly known as Dr. Strangelove, is a 1964 black comedy film which satirizes the nuclear scare. It was directed, produced, and co-written by Stanley Kubrick, starring Peter Sellers and George C. Scott, and featuring Sterling Hayden, Keenan Wynn, and Slim Pickens. The film is loosely based on Peter George's Cold War thriller novel Red Alert, also known as Two Hours to Doom.

The story concerns an unhinged United States Air Force general who orders a first strike nuclear attack on the Soviet Union. It follows the President of the United States, his advisors, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and a Royal Air Force (RAF) officer as they try to recall the bombers to prevent a nuclear apocalypse. It separately follows the crew of one B-52 as they try to deliver their payload.

In 1989, the United States Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry. It was listed as number three on AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs.

Contents

Plot

United States Air Force Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden), commander of Burpelson Air Force Base, initiates a plan to attack the Soviet Union with nuclear weapons in the paranoid belief that there is a Communist conspiracy involving water fluoridation and contamination of everyone's "precious bodily fluids". Ripper orders his nuclear-armed B-52s, which were holding at their fail-safe points, to move into Soviet airspace. Group Captain Lionel Mandrake (Peter Sellers), a Royal Air Force exchange officer serving as General Ripper's executive officer, issues the command on Ripper's order but later realizes it was not issued in retaliation to a Soviet attack on America. However Ripper refuses to disclose the three-letter recall code and locks the two of them in his office.

In the "War Room" at The Pentagon, General Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott) briefs President Merkin Muffley (Sellers). He reports that Ripper apparently took advantage of "Wing Attack Plan R," a wartime contingency plan which is intended to give Field Commanders authority to retaliate with nuclear weapons in the event that a Soviet first strike obliterates Washington, D.C. and incapacitates U.S. leadership. When President Muffley angrily begins to question the merits of this, the General responds that he does not "think it's quite fair to condemn a whole program because of a single slip-up". When Muffley proposes that troops be sent to the Air Force Base to seize Ripper (and hopefully force the recall code from him), Turgidson warns that General Ripper will have put the security forces there on high alert—ready to repel any outside force.

Turgidson tries to persuade Muffley to seize the moment and eliminate the Soviet Union by launching a full-scale attack on the Soviet Union. The General believes the United States is in a superior strategic position and a first strike would destroy the majority of the Soviets' missiles before they could retaliate. Without such a response, the US would be annihilated. Muffley refuses to have any part of such a scheme, and instead summons the Soviet ambassador, Alexei de Sadeski (Peter Bull). The Ambassador calls Soviet Premier Dimitri Kisov on the "Hot Line" and gives the Soviets information to help them shoot down the American planes, should they cross into Soviet airspace.

The Ambassador reveals that his side has installed a doomsday device that will automatically destroy life on Earth if there is a nuclear attack against the Soviet Union. The American President expresses amazement that anyone would build such a device. But Dr. Strangelove (Sellers), a former Nazi and weapons expert, admits that it would be "an effective deterrent... credible and convincing." However, a recent study by an American think tank had dismissed it as being too dangerous to be practical.

From his wheelchair, Strangelove explains the technology behind the Doomsday Machine and why it is essential that not only should it destroy the world in the event of a nuclear attack but also be fully automated and incapable of being deactivated. He further points out that the "whole point of the Doomsday Machine is lost if you keep it a secret". When asked why the Soviets did not publicize this, Ambassador de Sadeski sheepishly answers it was supposed to be announced the following Monday at the (Communist) Party Congress because "the Premier loves surprises."

U.S. Army forces arrive at Burpelson to arrest General Ripper. Because Ripper has warned his men that the enemy might attack disguised as American soldiers, the base's security forces open fire on them. A pitched battle ensues, which the Army forces finally win and Ripper, fearing torture to extract the recall code shoots himself. Colonel "Bat" Guano (Keenan Wynn) forces his way into Ripper's office and immediately suspects that Mandrake, whose uniform he does not recognize, is leading a mutiny and arrests him. Mandrake convinces Guano he must call the President with the recall code (OPE) which he has deduced from Ripper's desk blotter doodles but has to use a pay phone to do so. Guano has to shoot open a Coca-Cola machine to obtain coins for the phone, which he does reluctantly. Off camera, Mandrake finally contacts the Pentagon and is able to get the code combinations to the President and Strategic Air Command.

The correct recall code is issued to the planes and all those that have not been shot down by the Soviet military turn back toward base, except one. Its radio and fuel tanks were damaged by an anti-aircraft missile, leaving the plane unable either to receive the recall message or reach its primary or secondary targets, where the Soviets have concentrated all available defences at the urging of President Muffley. The pilot heads for the nearest target of opportunity, an ICBM complex. Aircraft commander Major T. J. "King" Kong (Slim Pickens) goes to the bomb bay to open the damaged doors manually, straddling a nuclear bomb as he repairs arcing wires overhead. When he effects his electrical patches, the bomb bay doors suddenly open, the bomb releases and Kong rides it to detonation like a rodeo cowboy, whooping and waving his cowboy hat. The H-bomb explodes and the Doomsday Device's detonation is inevitable.

In the War Room, Ambassador de Sadeski says life on Earth's surface will be extinct in ten months. Dr. Strangelove recommends the President gather several hundred thousand people to be relocated into deep mine shafts, where the radioactivity would never penetrate so the United States can be repopulated. Strangelove suggests a sex ratio of "ten females to each male," with the women selected for their stimulating sexual characteristics and the men selected for youth, health, intellectual capabilities and importance in business and government. He points out that with proper breeding techniques, the survivors could work themselves up to the present Gross National Product in 20 years and emerge after the radioactivity has ceased in about 100 years. At one point, Strangelove's errant right arm tries to give the Nazi salute and then strangle him.

General Turgidson warns of a possible "Mineshaft Gap" that might be a factor when the survivors emerge. De Sadeski walks away from the group and begins taking pictures of the war room's Big Board with a spy camera disguised as a pocketwatch. Just as Dr. Strangelove miraculously gets up from his wheelchair, takes a couple of steps and shouts, "Mein Führer! I can walk!," the Doomsday Machine activates. The film then cuts to a montage of nuclear detonations across the world, accompanied by Vera Lynn's recording of "We'll Meet Again."

Cast

- Peter Sellers as:

- Group Captain Lionel Mandrake, a British exchange officer.

- President Merkin Muffley, the American Commander-in-Chief.

- Dr. Strangelove, the wheelchair-bound nuclear war expert and former Nazi whose uncontrollable hand apparently has a Nazi mind of its own.

- George C. Scott as General Buck Turgidson, an over-the-top and jingoist General who does not trust the Soviet ambassador.

- Sterling Hayden as Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper, a paranoid ultra-nationalist. Jack the Ripper was a serial murderer in 19th century London.

- Keenan Wynn as Colonel Bat Guano, the Army officer who finds Mandrake and the dead Ripper. Bat guano is bat excrement, prized as an agricultural fertilizer.

- Slim Pickens as Major T. J. Kong, the B-52 Stratofortress bomber's commander and pilot.

- Peter Bull as Soviet Ambassador Alexei de Sadeski.

- James Earl Jones as Lieutenant Lothar Zogg, the B-52's bombardier.[1]

- Tracy Reed as Miss Scott, General Turgidson's secretary and mistress, the film's only female character. Reed also appears as "Miss Foreign Affairs," the centerfold in the June 1962 issue[2] of Playboy magazine that Major Kong is shown reading in the cockpit.[3]

- Shane Rimmer as Capt. "Ace" Owens, the B-52 co-pilot.

Peter Sellers's multiple roles

Columbia Pictures agreed to finance the film on condition that Peter Sellers play at least four major roles. This condition stemmed from the studio's impression that much of the success of Lolita (1962), Kubrick's previous film, was based on Sellers's performance in which his single character assumes a number of identities. Sellers had also played three roles in 1959's The Mouse That Roared. Kubrick accepted the demand, considering that "such crass and grotesque stipulations are the sine qua non of the motion-picture business."[4][5]

Sellers ended up playing just three of the four roles written for him. He was expected to play Air Force Major T. J. "King" Kong, the B-52 Stratofortress aircraft commander, but from the beginning Sellers was reluctant. He felt his workload was too heavy and he worried he would not properly portray the character's Texas accent. Kubrick pleaded with him and asked screenwriter Terry Southern (who had been raised in Texas) to record a tape with Kong's lines spoken in the correct accent. Using Southern's tape, Sellers managed to get the accent right, and started shooting the scenes in the airplane. But then Sellers sprained an ankle and could not work in the cramped cockpit set.[4][5][7]

Sellers is said to have improvised much of his dialogue, with Kubrick incorporating the ad-libs into the written screenplay so that the improvised lines became part of the canonical screenplay, a technique known as retroscripting.[8]

- Group Captain Lionel Mandrake

According to film critic Alexander Walker, the author of biographies of both Sellers and Kubrick, the role of Lionel Mandrake was the easiest of the three for Sellers to play, as he was aided by his experience of mimicking his superiors while serving in the RAF during World War II.[8] There is also a heavy resemblance to Sellers's friend and occasional co-star Terry-Thomas and the prosthetic-limbed RAF ace Douglas Bader.

- President Merkin Muffley

For his performance as President Merkin Muffley, Sellers flattened his natural English accent to resemble an American Midwesterner. Sellers drew inspiration for the role from Adlai Stevenson,[8] a former Illinois governor who was the Democratic candidate for the 1952 and 1956 presidential elections and the U.N. ambassador during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

In early takes, Sellers faked cold symptoms to emphasize the character's apparent weakness. This caused frequent laughter among the film crew, ruining several takes. Kubrick ultimately found this comic portrayal inappropriate, feeling that Muffley should be a serious character.[8] In later takes Sellers played the role straight, though the President's cold is still evident in several scenes.

In keeping with Kubrick's satirical character names, a "merkin" is a pubic hair wig. The president is bald, and his last name is "Muffley"; both are additional homages to a merkin.

- Dr. Strangelove

The title character, Dr. Strangelove, who was not in the original book,[9] serves as President Muffley's scientific advisor in the War Room, presumably making use of prior expertise as a Nazi physicist. When General Turgidson wonders aloud what kind of name "Strangelove" is, saying to Mr. Staines (Jack Creley) that it is not a Kraut name, Staines responds that Strangelove's original German surname was "Merkwürdigliebe," without mentioning that "Merkwürdigliebe" translates to "Strangelove" in English. Twice in the film, Strangelove 'accidentally' addresses the President as "Mein Führer."

The character is an amalgamation of RAND Corporation strategist Herman Kahn, mathematician and Manhattan Project principal John von Neumann, German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun and Edward Teller, the "father of the hydrogen bomb."[10] There is a common misconception that the character was based on Henry Kissinger, but Kubrick and Sellers denied this.[11] Kissinger was not a presidential adviser until 1969. The wheelchair-using Strangelove furthers a Kubrick trope of the menacing, seated antagonist, first depicted in Lolita through the character "Dr. Zaempf."[12] Strangelove's accent was influenced by that of Austrian-American photographer Weegee, who worked for Kubrick as a special photographic effects consultant.[8] Strangelove's appearance echoes the mad scientist archetype as seen in the character Rotwang in Fritz Lang's 1927 film Metropolis. Sellers's Strangelove takes from Rotwang the single black gloved hand (which in Rotwang's case is mechanical because of a lab accident), the wild hair and, most importantly, his inability to be completely controlled by political power.[13] According to film critic Alexander Walker, Sellers improvised Dr. Strangelove's lapse into the Nazi salute, borrowing one of Kubrick's black leather gloves for the uncontrollable hand that makes the gesture. Dr. Strangelove apparently suffers from diagonistic apraxia, or alien hand syndrome. Kubrick wore the gloves on the set to avoid being burned when handling hot lights, and Sellers, recognizing the potential connection to Lang's work, found them to be menacing.[8]

Slim Pickens as Major T. J. "King" Kong

Slim Pickens, an established character actor and veteran of many Western films, was eventually chosen to replace Sellers as Major Kong after Sellers's injury. Terry Southern's biographer, Lee Hill, said the part was originally written with John Wayne in mind, and that Wayne was offered the role after Sellers was injured but he immediately turned it down.[14] Dan Blocker of the Bonanza western television series was approached to play the part, but according to Southern, Blocker's agent rejected the script as being "too pinko."[15] Kubrick then recruited Pickens, whom he knew from working on Marlon Brando's One-Eyed Jacks.[14]

Fellow actor James Earl Jones recalls, "He was Major Kong on and off the set—he didn't change a thing—his temperament, his language, his behavior." Pickens was not told that the movie was a comedy and was only given the script for scenes he was in, to get him to play it "straight."[16]

Kubrick biographer John Baxter explained the documentary Inside the Making of Dr. Strangelove:

As it turns out, Slim Pickens had never left the United States. He had to hurry and get his first passport. He arrived on the set, and somebody said, "Gosh, he's arrived in costume!," not realizing that that's how he always dressed… with the cowboy hat and the fringed jacket and the cowboy boots—and that he wasn't putting on the character—that's the way he talked.

Pickens, who had previously played only minor supporting and character roles, said his appearance as Maj. Kong greatly improved his career. He later commented, "After Dr. Strangelove the roles, the dressing rooms and the checks all started getting bigger."[17]

George C. Scott as General Buck Turgidson

Kubrick tricked Scott into playing the role of Gen. Turgidson far more ridiculously than Scott was comfortable doing. Kubrick talked Scott into doing over the top "practice" takes, which Kubrick told Scott would never be used, as a way to warm up for the "real" takes. Kubrick used these takes in the final film, causing Scott to swear never to work with Kubrick again.[18]

During the filming, Kubrick and Scott had different opinions regarding certain scenes, but Kubrick got Scott to conform largely by repeatedly beating Scott at chess, which they played frequently on the set.[19] Scott, a skilled player himself, later said that while he and Kubrick may not have always seen eye to eye, he respected Kubrick immensely for his skill at chess.

Production

Novel and screenplay

Kubrick started with nothing but a vague idea to make a thriller about a nuclear accident, building on the widespread Cold War fear for survival.[20] While doing research, Kubrick gradually became aware of the subtle and unstable "balance of terror" between nuclear powers. At Kubrick's request, Alastair Buchan (the head of the Institute for Strategic Studies), recommended the thriller novel Red Alert by Peter George.[21] Kubrick was impressed with the book, which had also been praised by game theorist and future Nobel Prize in Economics winner Thomas Schelling in an article written for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and reprinted in The Observer,[22] and immediately bought the film rights.[23]

In collaboration with George, Kubrick started writing a screenplay based on the book. While writing the screenplay, they benefited from some brief consultations with Schelling and, later, Herman Kahn.[24] In following the tone of the book, Stanley Kubrick originally intended to film the story as a serious drama. But, as he later explained during interviews, he began to see comedy inherent in the idea of mutual assured destruction as he wrote the first draft. Kubrick said:

My idea of doing it as a nightmare comedy came in the early weeks of working on the screenplay. I found that in trying to put meat on the bones and to imagine the scenes fully, one had to keep leaving out of it things which were either absurd or paradoxical, in order to keep it from being funny; and these things seemed to be close to the heart of the scenes in question.[25]

After deciding to make the film a black comedy, Kubrick brought in Terry Southern as a co-writer. The choice was influenced by reading Southern's comic novel The Magic Christian, which Kubrick had received as a gift from Peter Sellers[4] (which, coincidentally, became a Sellers film in 1969).

Sets and filming

Dr. Strangelove was filmed at Shepperton Studios, in London, as Peter Sellers was in the middle of a divorce at the time, unable to leave England.[26] The sets occupied three main sound stages: the Pentagon War Room, the B-52 Stratofortress bomber and the last one containing both the motel room and General Ripper's office and outside corridor.[4] The studio's buildings were also used as the Air Force base exterior. The film's set design was done by Ken Adam, the production designer of several James Bond films (at the time he had already worked on Dr. No). The black and white cinematography was by Gilbert Taylor, and the film was edited by Anthony Harvey and Stanley Kubrick (uncredited). The original musical score for the film was composed by Laurie Johnson and the special effects were by Wally Veevers. The theme of the chorus from the bomb run scene is a modification of When Johnny Comes Marching Home.

For the War Room, Ken Adam first designed a two-level set which Kubrick initially liked, only to decide later that it was not what he wanted. Adam next began work on the design that was used in the film, an expressionist set that was compared with The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari and Fritz Lang's Metropolis. It was an enormous concrete room (130 feet (40 m) long and 100 feet (30 m) wide, with a 35-foot (11 m)-high ceiling[23]) suggesting a bomb shelter, with a triangular shape (based on Kubrick's idea that this particular shape would prove the most resistant against an explosion). One side of the room was covered with gigantic strategic maps reflecting in a shiny black floor inspired by the dance scenes in old Fred Astaire films. In the middle of the room there was a large circular table lit from above by a circle of lamps, suggesting a poker table. Kubrick insisted that the table be covered with green baize (although this could not be seen in the black and white film) to reinforce the actors' impression that they are playing 'a game of poker for the fate of the world.'[27] Kubrick asked Adam to build the set ceiling in concrete to force the director of photography to use only the on-set lights from the circle of lamps. Moreover, each lamp in the circle of lights was carefully placed and tested until Kubrick was happy with the result.[28]

Lacking cooperation from The Pentagon in the making of the film, the set designers reconstructed the cockpit to the best of their ability by comparing the cockpit of a B-29 Superfortress and a single photograph of the cockpit of a B-52, and relating this to the geometry of the B-52's fuselage. The B-52 was state-of-the-art in the 1960s, and its cockpit was off-limits to the film crew. When some United States Air Force personnel were invited to view the reconstructed B-52 cockpit, they said that "it was absolutely correct, even to the little black box which was the CRM."[8] It was so accurate that Kubrick was concerned whether Ken Adam's production design team had done all of their research legally, fearing a possible investigation by the FBI.[8]

In several shots of the B-52 flying over the polar ice en route to Russia, the shadow of the actual camera plane, a Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, is visible on the snow below. The B-52 was a scale model composited into the arctic footage which was sped up to create a sense of jet speed.[29] Home movie footage included in Inside the Making of Dr. Strangelove on the 2001 Special Edition DVD release of the film shows clips of the Fortress with a cursive "Dr. Strangelove" painted over the rear entry hatch on the right side of the fuselage.

Fail-Safe

Red Alert author Peter George collaborated on the screenplay with Kubrick and satirist Terry Southern. Red Alert was more solemn than its film version and it did not include the character of Dr. Strangelove, though the main plot and technical elements were quite similar. A novelization of the actual film, rather than a re-print of the original novel, was published by George, based on an early draft in which the film was meant to be bookended by aliens trying to understand what happened after arriving at a wrecked Earth.

During the filming of Dr. Strangelove, Stanley Kubrick learned that Fail-Safe, a film with a similar theme, was being produced. Although Fail-Safe was to be an ultra-realistic thriller, Kubrick feared that its plot resemblance would damage his film's box office potential, especially if it were released first. Indeed, the novel Fail-Safe (on which the film of the same name is based) is so similar to Red Alert that Peter George sued on charges of plagiarism and settled out of court.[30] What worried Kubrick most was that Fail-Safe boasted acclaimed director Sidney Lumet and first-rate dramatic actors Henry Fonda as the American President and Walter Matthau as the advisor to the Pentagon, Professor Groeteschele. Kubrick decided to throw a legal wrench into Fail-Safe's production gears. Lumet recalled in the documentary, Inside the Making of Dr. Strangelove: "We started casting. Fonda was already set… which of course meant a big commitment in terms of money. I was set, Walter [Bernstein, the screenwriter] was set… And suddenly, this lawsuit arrived, filed by Stanley Kubrick and Columbia Pictures."

Kubrick argued that Fail Safe's own 1960 source novel of the same name had been plagiarized from Peter George's Red Alert, to which Kubrick owned creative rights, and pointed out unmistakable similarities in intentions between the characters Groeteschele and Strangelove. The plan worked, and Fail-Safe opened eight months behind Dr. Strangelove, to critical acclaim but mediocre ticket sales.

Ending

The end of the film shows Dr. Strangelove exclaiming "Mein Führer, I can walk!" before cutting to footage of nuclear explosions, with Vera Lynn singing "We'll Meet Again." This footage comes from nuclear tests such as shot BAKER of Operation Crossroads at Bikini Atoll, the Trinity test, the bombing of Nagasaki, a test from Operation Sandstone and the great hydrogen bomb tests from Operation Redwing and Operation Ivy. In some shots old warships (such as the German heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen), which were used as targets, are plainly visible. In others the smoke trails of rockets used to create a calibration backdrop can be seen.

Original ending: The Pie Fight

It was originally planned for the film to end with a scene that was filmed, with everyone in the war room involved in a pie fight.

Accounts vary as to why the pie fight was cut. In a 1969 interview, Kubrick said: "I decided it was farce and not consistent with the satiric tone of the rest of the film."[26] Critic Alexander Walker observed that "the cream pies were flying around so thickly that people lost definition, and you couldn't really say whom you were looking at."[8] Nile Southern, son of screenwriter Terry Southern, suggested the fight was intended to be less jovial. "Since they were laughing, it was unusable, because instead of having that totally black, which would have been amazing, like, this blizzard, which in a sense is metaphorical for all of the missiles that are coming, as well, you just have these guys having a good old time. So, as Kubrick later said, 'it was a disaster of Homeric proportions.'"[8]

Former Goon Show writer, and friend of Sellers, Spike Milligan, was credited with suggesting the Vera Lynn music for the ending.

The Kennedy assassination

A first test screening of the film was scheduled for November 22, 1963, the day of the John F. Kennedy assassination. The film was just weeks from its scheduled premiere, but because of the assassination the release was delayed until late January 1964, as it was felt that the public was in no mood for such a film any sooner.

One line by Slim Pickens – "a fella could have a pretty good weekend in Dallas with all that stuff" – was dubbed to change "Dallas" to "Vegas," Dallas being the city where Kennedy was killed. The original reference to Dallas survives in some foreign language-dubbed versions of the film, including the French release.

The assassination also serves as another possible reason why the pie-fight scene was cut. In the scene General Turgidson exclaims, "Gentlemen! Our gallant young president has been struck down in his prime!" after Muffley takes a pie in the face. Editor Anthony Harvey states that "[the scene] would have stayed, except that Columbia Pictures were horrified, and thought it would offend the president's family."[31]

1994 Re-release

In 1994 the film was re-released. While the 1964 release used the 1.85:1 aspect ratio, the new print was in the 1.66:1 ratio, as Kubrick had originally intended.[32]

Themes

Satirizing the Cold War

Dr. Strangelove takes passing shots at numerous Cold War attitudes, such as the "missile gap", but it primarily focuses its satire on the theory of mutual assured destruction (MAD),[33] in which each side is supposed to be deterred from a nuclear war by the prospect of a universal cataclysmic disaster regardless of who "won". Military strategist and former physicist Herman Kahn, in his 1960 On Thermonuclear War, used the theoretical example of a doomsday machine to illustrate the concept of mutual assured destruction (MAD);[34] in effect, Kahn argued, both sides already had a sort of doomsday machine, since their nuclear arsenals were large enough to destroy most life on Earth. Kahn, a leading 1950s critic of American strategy, urged America to plan for a limited nuclear war, and later in the 1960s became one of the architects of the MAD doctrine. Kahn held that a nuclear war was inherently suicidal (because it is unwinnable) thus neither side would be willing to engage in all-out nuclear war. Kahn came off as cold and calculating, for example in his willingness to estimate how many human lives the USA could lose and still rebuild economically.[35] This attitude is reflected in Turgidson's remark to the president about the outcome of a pre-emptive nuclear war: "Mr. President, I'm not saying we wouldn't get our hair mussed. But I do say no more than ten to twenty million killed, tops, uh, depending on the breaks." Turgidson has a binder that is labelled "World Targets in Megadeaths", a term coined in 1953 by Kahn and popularized in his 1960 book On Thermonuclear War.

The plan to regenerate the human race from the people sheltered in mineshafts is a parody of Nelson Rockefeller's, Edward Teller's, Herman Kahn's, and Chet Holifield's 1961 plan to spend billions of dollars on a nationwide network of concrete-lined underground fallout shelters capable of holding millions of people.[36]

To refute early 1960s novels and Hollywood films like Fail-Safe and Dr. Strangelove which raised questions about U.S. control over nuclear weapons, the Air Force produced a documentary film--SAC Strategic Air Command Command Post--to demonstrate its responsiveness to presidential command and its tight control over nuclear weapons[37]

An entire book analyzing how the film reflected Cold War attitudes of the era is Dr. Strangelove's America: society and culture in the atomic age by Margot A. Henriksen (University of California Press, 1997).

Reception

The film is often ranked[by whom?] amongst the greatest[peacock term] of all time, and was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry. In 2000, readers of Total Film magazine voted it the 24th greatest comedy film of all time. It currently holds a 100% "Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 59 reviews.[38] It is ranked number 21 in the All-Time High Scores chart of Metacritic's Video/DVD section with an average score of 96,[39] and is currently ranked the 35th greatest film of all time at the Internet Movie Database.[40] It is also listed as number 26 on Empire's 500 Greatest Movies of All Time.

Roger Ebert has Dr. Strangelove in his list of Great Movies,[41] saying it is "arguably the best political satire of the century." It is also rated as the fifth greatest film in Sight & Sound’s directors’ poll – the only comedy in the top ten.[42]

Awards and honors

The film was nominated for four Academy Awards and also seven BAFTA Awards, of which it won four.

- Academy Awards nominations

- Best Actor in a Leading Role: Peter Sellers

- Best Adapted Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick, Peter George, Terry Southern

- Best Director: Stanley Kubrick

- Best Picture

- BAFTA Awards nominations

- Best British Actor: Peter Sellers

- Best British Screenplay: Stanley Kubrick, Peter George, Terry Southern

- Best Foreign Actor: Sterling Hayden

- BAFTA Awards won

- Best British Art Direction (Black and White): Ken Adam

- Best British Film

- Best Film From Any Source

- UN award.

In addition, the film won the best written American comedy award from the Writers Guild of America and a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation.

Kubrick himself won two awards for best director, from the New York Film Critics Circle and the Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists, and was nominated for one by the Directors Guild of America.

- American Film Institute recognition

- 1998 – AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies – #26

- 2000 – AFI's 100 Years... 100 Laughs – #3

- 2003 – AFI's 100 Years... 100 Heroes and Villains:

- Brigadier General Jack D. Ripper – nominated villain

- Dr. Strangelove – nominated villain

- 2005 – AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movie Quotes:

- "Gentlemen, you can't fight in here! This is the War Room!" – #64

- "Mein Führer! I can walk!" – nominated

- 2007 – AFI's 100 Years... 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) – #39

See also

- CRM 114

- Dead Hand

- Films considered the greatest ever

- Politics in fiction

- Stanley Kubrick Archive

- Operation Paperclip OSS program used to recruit scientists from Nazi Germany

References

Notes

- ^ WSJ.com, Opinion piece by James Earl Jones about Doctor Strangelove.

- ^ The distinctive bikinied torso on the cover dates this as the real June 1962 issue, which features the pictorial "A Toast to Bikinis" (being a play on the testing-site atoll for nukes), shown as the pinups on the inside of the B-52's safe door. Grant B. Stillman, "Last Secrets of Strangelove Revealed", 2008.

- ^ For the pose, Reed lay flat on her chest and had the January 1963 (Vol. 41, No. 2) issue of Foreign Affairs covering her buttocks. Despite this modest pose, her mother was furious. In the novel and advertising posters the Playboy model is referred to as "Miss Foreign Affairs." Brian Siano, "A Commentary on Dr. Strangelove", 1995 and "Inside the Making of Dr. Strangelove," a documentary included with the 40th Anniversary Special Edition DVD of the film.

- ^ a b c d Terry Southern, "Notes from The War Room", Grand Street, issue #49

- ^ a b Lee Hill, "Interview with a Grand Guy": interview with Terry Southern

- ^ Tulsa TV Memories. U.N.C.L.E., SAGE, SABRE, Strangelove & Tulsa: Connections

- ^ In the fictionalized biopic The Life and Death of Peter Sellers, it is suggested that Sellers faked the injury as a way to force Kubrick to release him from the contractual obligation to play this fourth role.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Inside the Making of Dr. Strangelove," a documentary included with the 40th Anniversary Special Edition DVD of the film

- ^ Jeffrey Townsend, et al., 'Red Alert' in John Tibbetts & James Welsh (eds), The Encyclopedia of Novels into Films, New York, 1999, pp. 183-6

- ^ Paul Boyer, 'Dr. Strangelove' in Mark C. Carnes (ed.), Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies, New York, 1996.

- ^ http://www.moviediva.com/MD_root/reviewpages/MDDrStrangelove.htm

- ^ http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/836-lolita

- ^ Frayling, Christopher. Mad, Bad, and Dangerous?: The Scientist and the Cinema. London: Reaktion, 2006. p.26

- ^ a b Lee Hill - A Grand Guy: The Life and Art of Terry Southern (Bloomsbury, 2001), pp.118-119

- ^ Biography for Dan Blocker at Internet Movie Database

- ^ "Movie Night!". Phenry.org. 1999-02-22. http://www.phenry.org/movies/movienight/strangelove.php. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- ^ Slim Pickens biography

- ^ James Earl Jones (2004-11-16). "A Bombardier's Reflection". Opinionjournal.com. http://atomiccafe.tribe.net/thread/f4a9a3d6-0f96-45c5-83f1-62ff060f2375. Retrieved 2010-03-06.

- ^ "Kubrick on The Shining" from Michel Ciment, 'Kubrick', Holt, Rinehart, and Winston; 1st American ed edition (1983), ISBN 0-03-061687-5

- ^ Brian Siano, "A Commentary on Dr. Strangelove", 1995

- ^ Alexander Walker, "Stanley Kubrick Directs," Harcourt Brace Co, 1972, ISBN 0-15-684892-9, cited in Brian Siano, "A Commentary on Dr. Strangelove", 1995

- ^ Phone interview with Thomas Schelling by Sharon Ghamari-Tabrizi, published in her book The Worlds of Herman Kahn; The Intuitive Science of Thermonuclear War (Harvard University Press, 2005) "Dr. Strangelove"

- ^ a b Terry Southern,"Check-up with Dr. Strangelove", article written in 1963 for Esquire but unpublished at the time

- ^ Sharon Ghamari-Tabrizi, "The Worlds of Herman Kahn; The Intuitive Science of Thermonuclear War", Harvard University Press, 2005.

- ^ Macmillan International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers, vol. 1, p. 126

- ^ a b "An Interview with Stanley Kubrick (1969)", published in Joseph Gelmis, The Film Director as Superstar, 1970, Doubleday and Company: Garden City, New York.

- ^ "A Kubrick Masterclass," interview with Sir Ken Adam by Sir Christopher Frayling, 2005; excerpts from the interview were published online at Berlinale talent capus and the Script Factory website

- ^ Interview with Ken Adam by Michel Ciment, published in Michel Ciment, "Kubrick," Holt, Rinehart, and Winston; 1st American ed edition (1983), ISBN 0-03-061687-5

- ^ The camera ship, a former USAAF B-17G-100-VE, serial 44-85643, registered F-BEEA, had been one of four Flying Fortresses purchased from salvage at Altus, Oklahoma in December 1947 by the French Institut géographique national and converted for survey and photo-mapping duty. It was the last active B-17 of a total of fourteen once operated by the IGN, but it was destroyed in a take-off accident at RAF Binbrook in 1989 during filming of the film Memphis Belle. "1944 USAAF Serial Numbers (44-83886 to 44-92098)". USAAS-USAAC-USAAF-USAF Aircraft Serial Numbers—1908 to Present. Joseph F. Baugher. http://home.att.net/~jbaugher/1944_6.html. Retrieved 2007-05-04.

- ^ "Red Alert — Peter Bryant — Microsoft Reader eBook". eBookMall, Inc.. http://www.ebookmall.com/ebook/72987-ebook.htm. Retrieved 2006-11-27.

- ^ "No Fighting in the War Room Or: Dr. Strangelove and the Nuclear Threat," a documentary included with the 40th Anniversary Special Edition DVD of the film

- ^ LoBrutto, Vincent. "Stanley Kubrick: A Biography". Da Capo Press, 1995, p. 250

- ^ King, Mike (2009). The American cinema of excess: extremes of the national mind on film. McFarland. p. 46. ISBN 0786439882, 9780786439881.

- ^ See On Thermonuclear War pp. 144-155

- ^ Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy, Volume 1. Simon and Schuster. 2001. p. 471. ISBN 0684806576, 9780684806570.

- ^ Fortune magazine November 1961 pages 112-115 et al.

- ^ http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/nukevault/ebb304/index.htm

- ^ "Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)". Rotten Tomatoes. http://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/dr_strangelove/. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "DVD/Video: All-Time High Scores". Metacritic. http://www.metacritic.com/video/highscores.shtml. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ^ "IMDb Top 250". Internet Movie Database. http://www.imdb.com/chart/top. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ Roger Ebert, "Dr. Strangelove (1964)", 11 July 1999

- ^ Sight & Sound’s directors’ poll

Bibliography

- Dolan Edward F. Jr. Hollywood Goes to War. London: Bison Books, 1985. ISBN 0-86124-229-7.

- Hardwick, Jack and Schnepf, Ed. "A Viewer's Guide to Aviation Movies." The Making of the Great Aviation Films, General Aviation Series, Volume 2, 1989.

- Henriksen, Margot A. (1987). Dr. Strangelove's America: Society and Culture in the Atomic Age. University of California Press. ISBN 0520083105. http://www.ucpress.edu/books/pages/6232.php.

- Oriss, Bruce. When Hollywood Ruled the Skies: The Aviation Film Classics of World War II. Hawthorne, California: Aero Associates Inc., 1984. ISBN 0-9613088-0-X.

- Rice, Julian (2008). Kubrick's Hope: Discovering Optimism from 2001 to Eyes Wide Shut. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0810862069.

External links

- Dr. Strangelove at the Internet Movie Database

- Dr. Strangelove at the TCM Movie Database

- Dr. Strangelove at AllRovi

- Dr. Strangelove at Rotten Tomatoes

- Checkup with Dr. Strangelove by Terry Southern

- Don't Panic covers Dr. Strangelove

- Continuity transcript

- Commentary on Dr. Strangelove by Brian Siano

- Last Secrets of Strangelove Revealed by Grant B. Stillman

- Study Guide by Dan Lindley. See also: longer version

- Annotated bibliography on Dr. Strangelove from the Alsos Digital Library

Films directed by Stanley Kubrick 1950s 1960s 1970s A Clockwork Orange (1971) · Barry Lyndon (1975)1980s The Shining (1980) · Full Metal Jacket (1987)1990s Eyes Wide Shut (1999)Shorts Related World Assembly of Youth (1952) • The Spy Who Loved Me (1977) • A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001) • Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures (2001) • Colour Me Kubrick (2006) • Stanley Kubrick's Boxes (2008)Other BAFTA Award for Best Film (1961–1980) Best Film from Any Source The Apartment (1961) · Ballad of a Soldier (1962) · The Hustler (1962) · Lawrence of Arabia (1963) · Tom Jones (1964) · Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1965) · My Fair Lady (1966) · Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1967) · A Man for All Seasons (1968)Best British Film Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1961) · A Taste of Honey (1962) · Lawrence of Arabia (1963) · Tom Jones (1964) · Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1965) · The Ipcress File (1966) · The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1967) · A Man for All Seasons (1968)Best Film The Graduate (1969) · Midnight Cowboy (1970) · Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1971) · Sunday Bloody Sunday (1972) · Cabaret (1973) · Day for Night (1974) · Lacombe, Lucien (1975) · Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore (1976) · One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1977) · Annie Hall (1978) · Julia (1979) · Manhattan (1980)Complete list · (1948–1960) · (1961–1980) · (1981–2000) · (2001–2020) The Incredible Shrinking Man (1958) · The Twilight Zone (1959) · The Twilight Zone (1960) · The Twilight Zone (1961) · The Twilight Zone (1962) · Dr. Strangelove (1965) · "The Menagerie" (Star Trek) (1967) · "The City on the Edge of Forever" (Star Trek) (1968) · 2001: A Space Odyssey (1969) · News coverage of Apollo 11 (1970) · A Clockwork Orange (1972) · Slaughterhouse-Five (1973) · Sleeper (1974) · Young Frankenstein (1975) · A Boy and His Dog (1976) · Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (1978) · Superman (1979) · Alien (1980)

Categories:- 1964 films

- English-language films

- American films

- 1960s comedy films

- American aviation films

- American black comedy films

- American political satire films

- Anti-war films

- Black-and-white films

- Cold War films

- Columbia Pictures films

- Fictional American people of German descent

- Films about nuclear war and weapons

- Films based on military novels

- Films directed by Stanley Kubrick

- Films set in the Arctic

- Films set on an airplane

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in Greenland

- Films shot in multiple formats

- Films set within one day

- Hugo Award Winners for Best Dramatic Presentation

- Mad scientist films

- Military humor in film

- United States Air Force in films

- United States National Film Registry films

- World War III speculative fiction

- Peter Sellers as:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.