- Bikini Atoll

-

Bikini Atoll

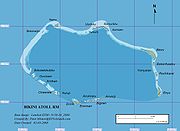

Pikinni Atoll— Atoll — Bikini Atoll, with Bikini Island boxed in the northeast. The crater formed by the Castle Bravo nuclear test can be seen on the northwest cape of the atoll.

FlagMap of the Marshall Islands show Bikini Map of Bikini Atoll Coordinates: 11°35′N 165°23′E / 11.583°N 165.383°ECoordinates: 11°35′N 165°23′E / 11.583°N 165.383°E Country Republic of the Marshall Islands Area – Land 2.3 sq mi (6 km2) Population – Total Uninhabited Official name: Bikini Atoll Nuclear Test Site Type: Cultural Criteria: iv, vi Designated: 2010 (34th session) Reference #: 1339 State Party: Marshall Islands Region: Asia-Pacific Bikini Atoll (pronounced /ˈbɪ.kɨˌni/ or /bɨˈki.ni/; Marshallese: Pikinni, /pʲɨkɨnʲnʲɨɦʲ/ or [pi͡ɯɡɯ͡innij])[1] is an atoll, listed as a World Heritage Site, in the Micronesian Islands of the Pacific Ocean, part of Republic of the Marshall Islands.

It consists of 23 islands surrounding a deep 229.4-square-mile (594.1 km2) central lagoon at the northern end of the Ralik Chain (approximately 87 kilometres (54 mi) northwest of Ailinginae Atoll and 850 kilometres (530 mi) northwest of Majuro), now universally significant to the world[2] as follows:

Bikini Atoll has conserved direct tangible evidence ... conveying the power of ... nuclear tests, i.e. the sunken ships sent to the bottom of the lagoon by the tests in 1946 and the gigantic Bravo crater ... Through its history, the atoll symbolises the dawn of the nuclear age, despite its paradoxical image of peace and of earthly paradise.Within Bikini Atoll, Bikini Island is the northeastern most and largest islet, measuring 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) long. About twelve kilometres to the northwest is the islet of Aomen. As part of the Pacific Proving Grounds it was the site of more than 20 nuclear weapons tests between 1946 and 1958.

The first Westerner to see the atoll, in the mid-1820s, was the Russian captain and explorer Otto von Kotzebue, who named the atoll Eschscholtz Atoll after the Russian scientist Johann Friedrich von Eschscholtz. The atoll, however, has always been called Bikini by the native Marshall Islanders, from Marshallese "Pik" meaning "surface" and "Ni" meaning "coconut". The name was popularized in the United States not only by nuclear bomb tests, but because the bikini swimsuit was named after the island in 1946. The two-piece swimsuit was introduced within days of the first nuclear test on the atoll, when the name of the island was in the news.[3] Introduced just weeks after the one-piece "Atome" was widely advertised as the "smallest bathing suit in the world", it was said that the bikini "split the atom".[4]

Contents

History

Humans have inhabited the atoll for at least 2,000 years.[5] Bikini was visited by only a dozen or so ships before the establishment of the German colony of the Marshall Islands in 1885. Along with the rest of the Marshalls, Bikini was captured by the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1914 during World War I and mandated to the Empire of Japan by the League of Nations in 1920. The Japanese administered the island under the South Pacific Mandate, but mostly left local affairs in hands of traditional local leaders until the start of World War II.

Following the end of World War II, Bikini came under the control of the United States as part of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands until the independence of the Marshall Islands in 1986.

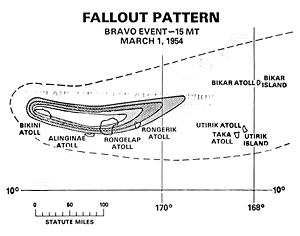

Between 1946 and 1958, twenty-three nuclear devices were detonated at Bikini Atoll, beginning with the Operation Crossroads series in July 1946. Preceding the nuclear tests, the indigenous population was relocated to Rongerik Atoll, though during the Castle Bravo detonation in particular some members of the population were exposed to nuclear fallout (see Project 4.1 for a discussion of the health effects). For examination of the fallout, several sounding rockets of the types Loki and Asp were launched at 11°35′N 165°20′E / 11.583°N 165.333°E.

The March 1, 1954 detonation, codenamed Castle Bravo, was the first test of a practical hydrogen bomb. The largest nuclear explosion ever set off by the United States, it was much more powerful than predicted, and created widespread radioactive contamination.[6][7][8]

Among those contaminated were the 23 crew members of the Japanese fishing boat Daigo Fukuryū Maru.[7] The ensuing scandal in Japan was enormous, and ended up inspiring the 1954 film Godzilla, in which the 1954 U.S. nuclear test awakens and mutates the monster, who then attacks Japan before finally being vanquished by Japanese ingenuity.

The Micronesian inhabitants, who numbered about 200 before the United States relocated them after World War II, ate fish, shellfish, bananas, and coconuts. A large majority of the Bikinians were moved to Kili Island as part of their temporary homestead, but remain there today and receive compensation from the United States government for their survival.[9]

In 1968 the United States declared Bikini habitable and started bringing a small group of Bikinians back to their homes in the early 1970s as a test. In 1978, however, the islanders were removed again when strontium-90 in their bodies reached dangerous levels after a French team of scientists did additional tests on the island.[10] It was not uncommon for women to experience faulty pregnancies, miscarriages, stillbirths, and damage to their offspring as a result of the nuclear testing on Bikini.[11] The United States provided $150 million as a settlement for damages caused by the nuclear testing program.[12]

Since the early 1980s the leaders of the Bikinian community have insisted that, because of what happened in the 1970s with the aborted return to their atoll, they want the entire island of Bikini excavated and the soil removed to a depth of about 15 inches (38 cm). Scientists involved with the Bikinians have stressed that while the excavation method would rid the island of the Cesium-137, the removal of the topsoil would severely damage the environment, turning it into a virtual wasteland of windswept sand. The Council, however, feeling a responsibility toward their people, has repeatedly contended that scraping Bikini is the only way to guarantee safe living conditions on the island for future generations.[citation needed]

Bikini Atoll was entered into the list of UNESCO World Heritage sites in August 2010.

Bikini Lagoon

Prior to the explosion of the first atomic bomb on the island, the lagoon at Bikini was designated as a ship graveyard after World War II by the United States Navy. Today the Bikini Lagoon is still home to a large number of vessels from the United States and other countries. The dangers of the radioactivity and limited services in the area led to divers staying away from one of the most remarkable potential scuba diving sites in the Pacific for many years. The dive spot has become popular among divers since 1996.[13] However, oil prices severely curtailed diving operations to the point of being suspended from August 2008 through 2009, restricted to fully self-contained vessels by prior arrangement.[14] The lagoon contains a larger amount of sea life than usual due to the lack of fishing, including sharks, increasing the fascination with the spot as a diver's adventure spot. Food, including fish, is contaminated so tour boats must bring all their own supplies.

Shipwrecks in the lagoon include:

- USS Saratoga (CV-3)

- USS Apogon (SS-308)

- USS Arkansas (BB-33)

- USS Gilliam (APA-57)

- USS Lamson (DD-367)

- USS Pilotfish (SS-386)

- Japanese battleship Nagato

Cross Spikes Club

The Cross Spikes Club was an improvised bar and hangout created by servicemen on Bikini Island between June and September 1946 during the preparation for Operation Crossroads. The "club" was little more than a small open air building that served alcohol to servicemen and provided outdoor entertainment, including a ping pong table.[16] The Cross Spikes Club has been described as "the only bright spot" in the Operation Crossroads experience. The club, like all military facilities on the island, was abandoned or dismantled following the completion of Operation Crossroads.

The island today

The special International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Bikini Advisory Group determined in 1997 that "It is safe to walk on all of the islands ... although the residual radioactivity on islands in Bikini Atoll is still higher than on other atolls in the Marshall Islands, it is not hazardous to health at the levels measured ... The main radiation risk would be from the food: eating locally grown produce, such as fruit, could add significant radioactivity to the body...Eating coconuts or breadfruit from Bikini Island occasionally would be no cause for concern. Eating many over a long period of time without having taken remedial measures, however, might result in radiation doses higher than internationally agreed safety levels." IAEA estimated that living in the atoll and consuming local food will exceed 15 mSv/year.[17]

The dose received from background radiation on the island was found to be between 2.4 mSv/year and 4.5 mSv/year (the lower rate is the same as natural background radiation), assuming that a diet of imported foods was available.[18] It was because of these food risks that the group eventually did not recommend fully resettling the island.

A 2002 survey found partial recovery of the corals inside The Bravo Crater.[19] Zoe Richards of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies and James Cook University observed matrices of branching Porites coral up to 8 meters high.[20]

See also

- Bikini – a type of swimsuit named after the island

- History of the bikini

- Daigo Fukuryū Maru

- Flag of Bikini Atoll

- Operation Castle

- Operation Ivy

References

Notes

- ^ Marshallese-English Dictionary - Place Name Index

- ^ UNESCO's World Heritage List "Bikini Atoll" entry Accessed 7 August 2010

- ^ "Swimsuit Trivia History of the Bikini". Swimsuit Style. http://www.swimsuit-style.com/bikini.html. Retrieved 2008-07-10.

- ^ Acton; Adams, Tania; Packer, Matt (2007). Origin of Everyday Things. New York: Sterling. p. 31. ISBN 978-1402743023.

- ^ p. 333 archive.org

- ^ Kaleem, Muhammad (2000). "Energy of a Nuclear Explosion". The Physics Factbook. http://hypertextbook.com/facts/2000/MuhammadKaleem.shtml. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- ^ a b Lorna Arnold and Mark Smith. (2006). Britain, Australia and the Bomb, Palgrave Press, p. 77.

- ^ John Bellamy Foster (2009). The Ecological Revolution: Making Peace with the Planet, Monthly Review Press, New York, p. 73.

- ^ "Bikini History". http://www.worldofdiving.com/html/bikinihistory.html. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- ^ "A Short History of the People of Bikini Atoll". http://www.bikiniatoll.com/history.html. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ^ "Victims of the Nuclear Age". http://www.ratical.org/radiation/NAvictims.html. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- ^ "Marshall Islands Nuclear Claims Tribunal". http://www.nuclearclaimstribunal.com/. Retrieved 2007-07-22.

- ^ Scuba Diving in Bikini Lagoon, diveadventures.com.au, accessed 2009-10-30

- ^ Bikini Atoll Dive Tourism Information, bikiniatoll.com, 2008-08-23, accessed 2009-10-30

- ^ "Operation Crossroads: Bikini Atoll". Navy Historical Center. Department of the Navy. http://www.history.navy.mil/ac/bikini/bikini1.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ^ "Article on Operation Crossroads mentioning Cross Spikes Club". Newsletter of American Atomic Veterans 25 (1). http://www.naav.com/newsletters/2006%20Vol%2025%20No%201%20Newsletter.pdf.

- ^ IAEA Bikini Advisory Group Report

- ^ Robison WL, Noshkin VE, Conrado CL, Eagle RJ, Brunk JL, Jokela TA, Mount ME, Phillips WA, Stoker AC, Stuart ML, Wong KM. (1997) The Northern Marshall Islands Radiological Survey: data and dose assessments Health Physics 73(1):37-48

- ^ Bikini Atoll coral biodiversity resilience five decades after nuclear testing

- ^ physorg.com Bikini corals recover from atomic blast

Bibliography

- Niedenthal, Jack, For the Good of Mankind: A History of the People of Bikini and their Islands, Bravo Publishers, (November 2002), ISBN 9829050025

- Wiesgall, Jonathan M, Operation Crossroads: Atomic Tests at Bikini Atoll, Naval Institute Press (21 April 1994), ISBN 1557509190

External links

- A Short History of the People of Bikini Atoll

- What About Radiation on Bikini Atoll?

- Department of Energy Marshall Islands Program: Chronology of nuclear testing, relocation of islanders and results of radiation tests

- Annotated bibliography for Bikini Atoll from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Islanders Want The Truth About Bikini Nuclear Test

- Marshall Islands site

- Entry at Oceandots.com

Marshall Islands - Bold indicates populated islands

- Italics indicate single island

Ratak Chain (Sunrise, Eastern)

Ralik Chain (Sunset, Western) Categories:

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.