- Operation Castle

-

Operation Castle

Castle RomeoInformation Country United States Test site Pacific Proving Grounds Period March - May 1954 Number of tests 6 Test type Atmospheric Device type Thermonuclear Max. yield 15 megatons of TNT (63 PJ) Navigation Previous test Operation Upshot-Knothole Next test Operation Teapot Operation Castle test video

Operation Castle was a United States series of high-energy (high-yield) nuclear tests by Joint Task Force SEVEN (JTF-7) at Bikini Atoll beginning in March 1954. It followed Operation Upshot-Knothole and preceded Operation Teapot.

Conducted as a joint venture between the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) and the Department of Defense (DoD), the ultimate objective of the operation was to test designs for an aircraft-deliverable thermonuclear weapon.

Operation Castle was considered by government officials to be a success as it proved the feasibility of deployable "dry fuel" designs for thermonuclear weapons. There were technical difficulties with some of the tests: one device had a yield much lower than its predicted yield (a "fizzle"), while two other devices detonated with over twice their predicted yields. One test in particular, Castle Bravo, resulted in extensive radiological contamination of nearby islands (including inhabitants and U.S. soldiers stationed there), as well as a nearby Japanese fishing boat (Daigo Fukuryū Maru), resulting in one direct fatality and continued health problems for many of those exposed. Public reaction to the tests and an awareness of the long-range effects of nuclear fallout has been attributed as being part of the motivation for the Partial Test Ban Treaty of 1963.

Contents

Background

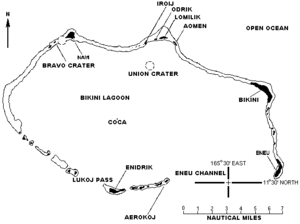

Bikini Atoll had previously hosted nuclear testing in 1946 as part of Operation Crossroads where the world’s fourth and fifth atomic weapons were detonated in Bikini Lagoon. Since then, US nuclear weapons testing had moved to Eniwetok Atoll to take advantage of generally larger islands and deeper water. Both Atolls were part of the US Pacific Proving Grounds.

The extremely high yields of the Castle weapons caused concern within the AEC that potential damage to the limited infrastructure already established at Eniwetok would delay other operations. Additionally, the cratering from the Castle weapons was expected to be comparable to that of Ivy Mike, a 10.4 megaton device tested at Eniwetok in 1952 leaving a crater approximately 1 mile (1.6 km) in diameter marking the location of the obliterated test island Elugelab.[1]

The Ivy 'Mike' test was the world's first "hydrogen bomb", producing a full-scale thermonuclear or fusion explosion. The 'Mike' device used liquid deuterium, an isotope of hydrogen, making it a "wet bomb." The complex dewar mechanisms needed to store the liquid deuterium at cryogenic temperatures made the device three stories tall and 82 tons in total weight, far from being a deliverable weapon.[2] With the success of Ivy 'Mike' as proof of the Teller-Ulam bomb concept, research began on using a “dry" fuel to make a practical fusion weapon so that the United States could begin production and deployment of thermonuclear weapons in quantity. The final result incorporated lithium deuteride as the fusion fuel in the Teller-Ulam design, vastly reducing size and weight and simplifying the overall design. Operation Castle was charted to test four dry fuel designs, two wet bombs, and one smaller device. Approval for Operation Castle was communicated to JTF-7 by Major General Kenneth D. Nichols, General Manager of the AEC, on 21 January 1954.

Experiments

Operation Castle was organized into seven experiments, all but one of which were to take place at Bikini Atoll. Below is the original test schedule (as of February 1954).[3]

Operation Castle Schedule Experiment Device Prototype Fuel Date Predicted yield Manufacturer Test location BRAVO Shrimp TX-21 40% Li-6 D (dry) 1 March 1954 6 Mt Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory Reef off Nam Is, Bikini UNION Alarm Clock EC-14 95% Li-6 D (dry) 11 March 1954 3-4 Mt Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory Barge off Iroij, Bikini YANKEE Jughead / Runt-II TX/EC-16 / TX/EC-24 Cryo H-2 (wet) / 40% Li-6 D (dry) 22 March 1954 8 Mt Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory Barge off Iroij, Bikini ECHO Ramrod N/A Cryo H-2 (wet) 29 March 1954 65-275 Kt University of California Radiation Laboratory (Livermore) Eleleron, Enewetak NECTAR Zombie TX-15 Boosted fission 5 April 1954 1.8 Mt Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory Barge off Iroij, Bikini ROMEO Runt TX/EC-17A 7.5% Li-6 D (natural) 15 April 1954 4 Mt Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory Barge off Iroij, Bikini KOON Morgenstern N/A 7.6% Li-6 D (natural) 22 April 1954 1 Mt University of California Radiation Laboratory (Livermore) Eneman, Bikini Operation Castle was intended to test lithium deuteride (LiD) as a thermonuclear fusion fuel. A solid at room temperature, "dry" LiD, if it worked, would be far more practical than the cryogenic liquid deuterium fuel in the Ivy Mike device. The same Teller-Ulam principle would be used as in the Ivy Mike "Sausage" device, but the fusion reactions were different. Mike fused deuterium with deuterium, but the LiD devices would fuse deuterium with tritium. The tritium was produced during the explosion by irradiating the lithium with fast neutrons.

Bravo and Union used lithium enriched in the Li-6 isotope while Romeo and Koon were fueled with natural lithium (92% Li-7, 7.5% Li-6). The use of natural lithium would be important to the ability of the US to rapidly expand its nuclear stockpile during the Cold War arms race.

As a hedge, development of liquid deuterium weapons continued in parallel. Even though they were much less practical because of the logistical problems dealing with the transport, handling, and storage of a cryogenic device, the cold war arms race drove the demand for a viable fusion weapon. The Ramrod and Jughead devices were liquid fuel designs greatly reduced in size and weight from their Ivy Mike "Sausage" predecessor. The Jughead device was ultimately weaponized and saw limited fielding in the inventory until the dry fuel weapons were common.

Nectar was not a fusion weapon in the same sense as the rest of the Castle series. Even though it used a dry lithium fuel for fission boosting, the principal reaction material in the second stage was uranium and plutonium. Similar to the Teller-Ulam configuration, a fission device was used to create high temperatures and pressures in order to compress a second fissionable mass that would have otherwise been too large to sustain an efficient reaction if it were triggered with conventional explosives. This experiment was intended to develop intermediate yield weapons for expanding the inventory (around 1-2 Mt vs. 4-8).

Many "fusion" or "thermonuclear" weapons generate much, or even most, of their yields from fission. Although the U-238 isotope of uranium will not sustain a chain reaction, it still fissions when irradiated by the intense fast neutron flux of a fusion explosion. Because U-238 is plentiful and has no critical mass, it can be added in almost unlimited quantities as a "tamper" around a fusion bomb, helping to contain the fusion reaction and contributing its own fission energy. Fission of the U-238 tamper contributed 77% (8 megatons) to the yield of the 10.4 Mt Ivy Mike explosion.

Test execution

The most notable event of Operation Castle was the 'Castle Bravo' test. The dry fuel for 'Bravo' was 40% Li-6 and 60% Li-7. Only the Li-6 was expected to breed tritium for the deuterium-tritium fusion reaction; the Li-7 was expected to be inert. Yet J. Carson Mark, head of the Los Alamos Theoretical Design Division, had speculated that 'Bravo' could "go big", estimating that the device could produce an explosive yield as much as 20% more than had been originally calculated.[4] Consequently, the Li-7 component turned out to be an excellent source of tritium through a previously unquantified reaction. In actuality, 'Bravo' exceeded expectations by 250%, yielding 15 Mt -- 1,000 times more powerful than the Little Boy weapon used on Hiroshima. Castle 'Bravo' remains to this day the largest atmospheric detonation ever conducted by the United States, and the seventh largest ever detonated in the world.

Because Castle 'Bravo' greatly exceeded its expected yield, JTF-7 was caught unprepared. Much of the permanent infrastructure on Bikini Atoll was heavily damaged. The intense thermal flash ignited a fire at a distance of 20 nautical miles (37 km) on the island of Eneu (base island of Bikini Atoll).[5] The ensuing fallout contaminated all of the atoll, so much so, that it could not be approached by JTF-7 for 24 hours after the test, and even then exposure times were limited.[6] As the fallout spread downwind to the east, more atolls were contaminated by radioactive calcium ash from the incinerated underwater coral banks. Although the atolls were evacuated soon after the test, 239 Marshallese on the Utirik, Rongelap, and Ailinginae Atolls were subjected to significant levels of radiation. 28 Americans stationed on the Rongerik Atoll were also exposed. Follow-up studies of the contaminated individuals began soon after the blast as Project 4.1, and though the short-term effects of the radiation exposure for most of the Marshallese were mild and/or hard to correlate, the long-term effects were pronounced. Additionally, 23 Japanese fishermen aboard Lucky Dragon No. 5 were also exposed to high levels of radiation. They suffered symptoms of radiation poisoning, and one crew member died in September 1954.

The heavy contamination and extensive damage from 'Bravo' significantly delayed the rest of the series. The post-'Bravo' schedule was revised on 14 April 1954.[7]

Operation Castle Schedule (Post BRAVO) Experiment Original date Revised date Original yield Revised yield UNION 11 March 1954 22 April 1954 3-4 Mt 5-10 Mt YANKEE 22 March 1954 27 April 1954 8 Mt 9.5 Mt NECTAR 5 April 1954 20 April 1.8 Mt 1-3 Mt ROMEO 15 April 1954 27 March 1954 4 Mt 8 Mt KOON 22 April 1954 7 April 1954 1 Mt 1.5 Mt The 'Romeo' and 'Koon' tests were complete by the time of this revision. The 'Echo' test was canceled due to the liquid fuel design becoming obsolete with the success of dry-fueled 'Bravo'. 'Yankee' was similarly considered obsolete and so was conducted using a Runt II device (similar to the 'Union' device) hastily completed at Los Alamos and flown to Bikini. With this revision, both of the "wet" fuel devices were removed from the test schedule.

As Operation Castle continued, the increased yields and fallout caused test locations to be re-evaluated. While the majority of the tests were planned for barges near the sand spit of Iroij, some were moved to the 'Bravo' and 'Union' craters. Additionally, Castle 'Nectar' was moved from Bikini Atoll to the Ivy 'Mike' crater at Eniwetok for expediency since Bikini was still heavily contaminated from the previous tests.[8]

The final test in Operation Castle took place on 14 May 1954.

Operation Castle (Actual) Experiment Date Yield Location BRAVO 1 March 1954 15Mt Reef off Nam Is, Bikini ROMEO 27 March 1954 11 Mt Barge in BRAVO crater, Bikini KOON 7 April 1954 110 kt Eneman, Bikini UNION 26 April 1954 6.9 Mt Barge off Iroij, Bikini YANKEE 5 May 1954 13.5 Mt Barge in UNION, Bikini NECTAR 14 May 1954 1.69 Mt Barge Ivy-MIKE crater, Enewetak Results

Operation Castle was an unqualified success for the implementation of dry fuel devices. The Bravo design was quickly weaponized and is suspected to be the progenitor of the Mk-21 gravity bomb. The Mk-21 design project began on 26 March 1954 (just three weeks after Bravo) with production of 275 weapons beginning in late 1955. Romeo, relying on natural lithium, was rapidly turned into the Mk-17 bomb, the US first deployable H bomb,[9] and was available to strategic forces as an Emergency Capability by mid-1954. Most of the Castle dry fuel devices eventually appeared in the inventory and ultimately grandfathered the majority of thermonuclear configurations.

In contrast, the Livermore-designed Koon design was a failure. Using natural lithium and a heavily modified Teller-Ulam configuration, the test produced only 110 Kt of an expected 1.5 Mt. While engineers at the Radiation Laboratory had hoped it would lead to a promising new field of weapons, it was eventually determined that the design allowed premature heating of the lithium fuel, thereby disrupting the delicate fusion conditions.

See also

References

- ^ Operation Ivy, pg 192

- ^ Dark Sun, pg 495.

- ^ Castle Series, pg 247

- ^ O'Keefe, page 179

- ^ Castle Series, pg 209

- ^ Hacker, pg 140

- ^ Castle Series pg 268

- ^ Castle Series pg 248.

- ^ Development of the Mk 17 bomb, Atomic Museum.com

Bibliography

- The United States Department of Defense; Defense Nuclear Agency (1982). Castle Series. Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office.

- The United States Department of Defense; Defense Nuclear Agency (1983). Operation Ivy--1952. Washington DC: United States Government Printing Office.

- Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster.

- O'Keefe, Bernard J. (1983). Nuclear Hostages. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Hacker, Barton C (1994). Elements of Controversy: The Atomic Energy Commission and Radiation Safety in Nuclear Weapons Testing. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

External links

- Downloadable/Streamable Declassified Film: Operation Castle Commanders Report, at the Internet Archive

- Downloadable/Streamable Declassified Film: Military Effects Studies Operation Castle, at the Internet Archive

- Operation Castle

Coordinates: 11°41′50″N 165°16′19″E / 11.69722°N 165.27194°E

Categories:- American nuclear explosive tests

- 1954

- Bikini Atoll

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.