- DNA ligase

-

DNA ligase

DNA ligase repairing chromosomal damage Identifiers EC number 6.5.1.1 CAS number 9015-85-4 Databases IntEnz IntEnz view BRENDA BRENDA entry ExPASy NiceZyme view KEGG KEGG entry MetaCyc metabolic pathway PRIAM profile PDB structures RCSB PDB PDBe PDBsum Gene Ontology AmiGO / EGO Search PMC articles PubMed articles ligase I, DNA, ATP-dependent

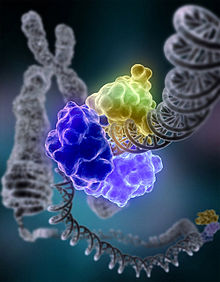

Identifiers Symbol LIG1 Entrez 3978 HUGO 6598 OMIM 126391 RefSeq NM_000234 UniProt P18858 Other data Locus Chr. 19 [1] ligase III, DNA, ATP-dependent Identifiers Symbol LIG3 Entrez 3980 HUGO 6600 OMIM 600940 RefSeq NM_002311 UniProt P49916 Other data Locus Chr. 17 q11.2-q12 ligase IV, DNA, ATP-dependent Identifiers Symbol LIG4 Entrez 3981 HUGO 6601 OMIM 601837 RefSeq NM_002312 UniProt P49917 Other data Locus Chr. 13 q33-q34 In molecular biology, DNA ligase is a specific type of enzyme, a ligase, (EC 6.5.1.1) that repairs single-stranded discontinuities in double stranded DNA molecules, in simple words strands that have double-strand break (a break in both complementary strands of DNA). Purified DNA ligase is used in gene cloning to join DNA molecules together. The alternative, a single-strand break, is fixed by a different type of DNA ligase using the complementary strand as a template,[1] but still requires DNA ligase to create the final phosphodiester bond to fully repair the DNA.

DNA ligase has applications in both DNA repair and DNA replication (see Mammalian ligases). In addition, DNA ligase has extensive use in molecular biology laboratories for Genetic recombination experiments (see Applications in molecular biology research).

Contents

Ligase mechanism

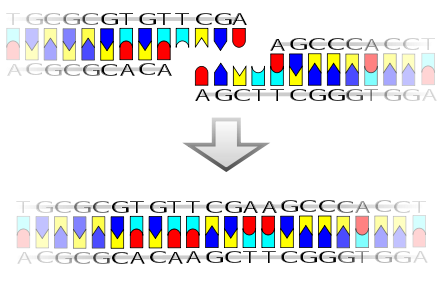

The mechanism of DNA ligase is to form two covalent phosphodiester bonds between 3' hydroxyl ends of one nucleotide, ("acceptor") with the 5' phosphate end of another ("donor"). ATP is required for the ligase reaction, which proceeds in three steps: (1) adenylation (addition of AMP) of a residue in the active center of the enzyme, pyrophosphate is released; (2) transfer of the AMP to the 5' phosphate of the so-called donor, formation of a pyrophosphate bond; (3) formation of a phosphodiester bond between the 5' phosphate of the donor and the 3' hydroxyl of the acceptor.[2]

Ligase will also work with blunt ends, although higher enzyme concentrations and different reaction conditions are required.

Mammalian ligases

In mammals, there are four specific types of ligase.

- DNA ligase I: ligates the nascent DNA of the lagging strand after the Ribonuclease H has removed the RNA primer from the Okazaki fragments.

- DNA ligase II: alternatively spliced form of DNA ligase III found in non-dividing cells.

- DNA ligase III: complexes with DNA repair protein XRCC1 to aid in sealing DNA during the process of nucleotide excision repair and recombinant fragments.

- DNA ligase IV: complexes with XRCC4. It catalyzes the final step in the non-homologous end joining DNA double-strand break repair pathway. It is also required for V(D)J recombination, the process that generates diversity in immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor loci during immune system development.

Some forms of DNA ligase present in bacteria (usually larger) may require NAD to act as a co-factor, whereas other forms of DNA ligases (usually present in E.coli, and usually smaller) may require ATP to react. Also, a number of other structures present in the DNA ligase are the AMP and lysine, both of which are important in the ligation process since they create an intermediate enzyme.

Applications in molecular biology research

DNA ligases have become an indispensable tool in modern molecular biology research for generating recombinant DNA sequences. For example, DNA ligases are used with restriction enzymes to insert DNA fragments, often genes, into plasmids.

One vital aspect to performing efficient recombination experiments involving the ligation of cohesive-ended fragments is controlling the optimal temperature. Most experiments use T4 DNA Ligase (isolated from bacteriophage T4), which is most active at 25°C. However, for optimal ligation efficiency with cohesive-ended fragments ("sticky ends"), the optimal enzyme temperature needs to be balanced with the melting temperature Tm (also the annealing temperature) of the sticky ends being ligated.[3] If the ambient temperature exceeds Tm, the homologous pairing of the sticky ends would not be stable because the high temperature disrupts hydrogen bonding.[4] Ligation reaction is most efficient when the sticky ends are already stably annealed, disruption of the annealing ends would therefore results in low ligation efficiency. The shorter the overhang, the lower the Tm, typically a 4-base overhang has a Tm of 12-16°C.

Since blunt-ended DNA fragments have no cohesive ends to anneal, the melting temperature is not a factor to consider within the normal temperature range of the ligation reaction. However, the higher the temperature, the less chance that the ends to be joined will be aligned to allow ligation (molecules move around the solution more at higher temperatures). The limiting factor in blunt end ligation is not the activity of the ligase but rather the number of alignments between DNA fragment ends that occur. The most efficient ligation temperature for blunt-ended DNA would therefore be the temperature at which the greatest number of alignments can occur. Therefore, the majority of blunt-ended ligations are carried out at 14-16°C overnight. The absence of a stably annealed ends also means that the ligation efficiency is lowered, requiring a higher ligase concentration to be used.(T4 DNA ligase is the only commercially-available DNA ligase to anneal blunt ends).[3]

History

The first DNA ligase was purified and characterized in 1967. The common commercially available DNA ligases were originally discovered in bacteriophage T4, E. coli and other bacteria.[5]

See also

- DNA end

- Lagging strand

- DNA replication

- Okazaki fragment

- DNA Polymerase

References

- "RCSB Protein Data Bank - Structure Summary for 1X9N - Crystal Structure of Human DNA Ligase I bound to 5'-adenylated, nicked DNA". http://www.rcsb.org/pdb/explore/explore.do?structureId=1X9N.

- ^ Pascal, John M.; O'Brien, Patrick J.; Tomkinson, Alan E.; Ellenberger, Tom (2004). "Human DNA ligase I completely encircles and partially unwinds nicked DNA". Nature 432 (7016): 473–8. doi:10.1038/nature03082. PMID 15565146.

- ^ Lehnman, I. R. (1974). "DNA Ligase: Structure, Mechanism, and Function". Science 186 (4166): 790–7. doi:10.1126/science.186.4166.790. PMID 4377758.

- ^ a b Tabor, Stanley. DNA ligases. Chapter in: Current Protocols in Molecular Biology, Book 1. 2001: Wiley Interscience.[page needed]

- ^ Law-breaking liquid defies the rules at physicsworld.com

- ^ Weiss, B.; Richardson, CC (1967). "Enzymatic Breakage and Joining of Deoxyribonucleic Acid, I. Repair of Single-Strand Breaks in DNA by an Enzyme System from Escherichia coli Infected with T4 Bacteriophage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 57 (4): 1021–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.57.4.1021. PMC 224649. PMID 5340583. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=224649.

External links

- DNA Ligase: PDB molecule of the month

- Davidson College General Information on Ligase

- OpenWetWare DNA Ligation Protocol

6.5: Phosphoric Ester DNA ligase6.6: Nitrogen-Metal DNA replication (Prokaryotic, Eukaryotic) Separation

and initiationPre-replication complex: Origin recognition complex (ORC1, ORC2, ORC3, ORC4, ORC5, ORC6) · Minichromosome maintenance (MCM2 · MCM3 · MCM4 · MCM5 · MCM6 · MCM7) · CDC6

Autonomously replicating sequence

Single-strand binding protein (SSBP2, SSBP3, SSBP4)

RNase H (RNASEH1, RNASEH2A)

Helicase: HFM1

Primase: PRIM1 · PRIM2BothOrigin of replication/Ori/Replicon

Replication fork (Lagging and leading strands) · Okazaki fragment · PrimerReplication DNA polymerase III holoenzyme (dnaC, dnaE, dnaH, dnaN, dnaQ, dnaT, dnaX) · Replisome · DNA ligase · DNA clamp · Topoisomerase (DNA gyrase)

Prokaryotic DNA polymerase: DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment)Replication factor C (RFC1) · Flap endonuclease (FEN1) · Topoisomerase · Replication protein A (RPA1)

Eukaryotic DNA polymerase: delta (POLD1, POLD2, POLD3, POLD4)

DNA clamp (PCNA)BothTermination Categories:- Genes on chromosome 19

- Genes on chromosome 17

- Genes on chromosome 13

- EC 6.5

- Molecular biology

- DNA replication

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.