- Crimean Tatars

-

Crimean Tatars

(Qırımtatarlar)

Amet-khan Sultan • Toğay Bey

I. Gasprinski • N. Çelebicihan • M. A. QırımoğluTotal population 500,000[citation needed] Regions with significant populations  Crimea: 243,400[1]

Crimea: 243,400[1]

(out of 248,200[2] in Ukraine)

Ukraine) Turkey

Turkeyup to 500,000[citation needed]  Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan10,046[3], 90,000[4], 188,772[5]  Romania

Romania24,137[6]  Russia

Russia4,131[7]  Bulgaria

Bulgaria1,803[8]  Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan1,532[9] Languages Religion Related ethnic groups other Turkic peoples

Crimean Tatars (sg. Qırımtatar, pl. Qırımtatarlar) or Crimeans (sg. Qırım, Qırımlı, pl. Qırımlar, Qırımlılar) are a Turkic ethnic group that originally resided in Crimea. They speak the Crimean Tatar language. They are not to be confused with the Volga Tatars.

In modern times, in addition to living in Crimea, Ukraine, there is a large diaspora of Crimean Tatars in Turkey, Romania, Bulgaria, Uzbekistan, Western Europe, the Middle East and North America, as well as small communities in Finland, Lithuania, Russia, Belarus and Poland. (See Crimean Tatar diaspora)

Contents

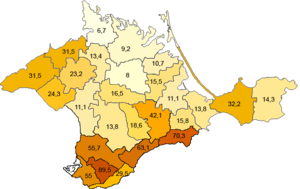

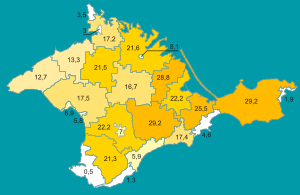

Distribution

Today, more than 240,000 Crimean Tatars live in Crimea and about 150,000 remain in exile in Central Asia, mainly in Uzbekistan. There is an unspecified number of people of Crimean Tatar origin living in Turkey, descendants of those who emigrated in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the Dobruja region straddling Romania and Bulgaria, there are more than 27,000 Crimean Tatars: 24,000 on the Romanian side, and 3,000 on the Bulgarian side[citation needed].

Subethnic groups

The Crimean Tatars are subdivided into three sub-ethnic groups:

- the Tats (not to be confused with Tat people, living in the Caucasus region) who used to inhabit the mountainous Crimea before 1944 (about 55%),

- the Yalıboyu who lived on the southern coast of the peninsula (about 30%),

- the Noğay (not to be confused with Nogai people, living now in Southern Russia) - former inhabitants of the Crimean steppe (about 15%).

The Tats and Yalıboyus have a Caucasoid physical appearance, while the Noğays retain some Mongoloid physical appearance.

History

See also: Demographic history of CrimeaCrimean Khanate

The Crimean Tatars emerged as a nation at the time of the Crimean Khanate. The Crimean Khanate was a Turkic-speaking Muslim state which was among the strongest powers in Eastern Europe until the beginning of the 18th century.[10] The Crimean Tatars adopted Islam in the 13th century and thereafter Crimea became one of the centers of Islamic civilization. According to Baron Iosif Igelström, in 1783 there were close to 1600 mosques and religious schools in Crimea. In Bakhchisaray, the khan Meñli I Giray built Zıncırlı Medrese (literally "Chain Madrassah"), an Islamic seminary where one has to bow while entering from its door because of the chain hanging over. This symbolized the Crimean society's respect for learning. Meñli I Giray also constructed a large mosque on the model of Hagia Sophia (which was ruined in 1850s). Later, the khans built a greater palace, Hansaray in Bakhchisaray, which survives to this day. Sahib I Giray patronized many scholars and artists in this palace. During the reign of Devlet I Giray the architect Mimar Sinan built a mosque, Cuma Cami, in Kezlev. The Crimean Khanate became a protectorate of the Ottoman Empire in 1475, when the Ottoman general Gedik Ahmed Pasha conquered the southern coast of Crimea. The alliance with the Ottomans became an important factor in the survival of the khanate until the 18th century.

Slave trade

Until the beginning of the 18th century, Crimean Tatars were known for frequent, at some periods almost annual, devastating raids into Ukraine and Russia.[11] For a long time, until the early 18th century, the Crimean Khanate maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East which was the most important basis of its economy.[11] One of the most important trading ports and slave markets was Kefe.[11] Some researchers estimate that altogether more than 3 million people, predominantly Ukrainians but also Russians, Belarusians and Poles, were captured and enslaved during the time of the Crimean Khanate in what was called "the harvest of the steppe".[12][13] On the other hand, lands of Crimean Tatars were also being raided by Cossacks.[14] A constant threat from Crimean Tatars was one of the reasons for the formation of Cossacks, armed Slavic horsemen, who often repelled attacks and liberated captives from Crimean Tatars.[citation needed] The Don and Zaporozhian Cossacks also managed to raid Crimean Tatars land.[citation needed] The last recorded major Crimean raid, before those in the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774) took place during the reign of Peter I (1682–1725)[14] However, Cossack raids continued during that time, Ottoman Grand Vizier complained to the Russian consul about raids to Crimea and Özi in 1761.[14]

In the Russian Empire

The Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774 resulted in the defeat of the Ottomans by the Russians, and according to the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774) signed after the war, Crimea became independent and Ottomans renounced their political right to protect the Crimean Khanate. After a period of political unrest in Crimea and a number of violations of the treaty by Crimeans and Ottomans, Russia also violated the treaty and annexed the Crimean Khanate in 1783. After the annexation, under pressure of Slavic colonization, Crimean Tatars began to abandon their homes and move to the Ottoman Empire in continuing waves of emigration. Particularly, the Crimean War of 1853-1856, the laws of 1860-63 and the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878 caused an exodus of the Crimean Tatars. Of total Tatar population 300,000 of the Tauride Province about 200,000 Crimean Tatars emigrated.[15] Many Crimean Tatars perished in the process of emigration, including those who drowned while crossing the Black Sea. Today the descendants of these Crimeans form the Crimean Tatar diaspora in Bulgaria, Romania and Turkey.

Ismail Gasprinski (1851–1914) was a renowned Crimean Tatar intellectual, whose efforts laid the foundation for the modernization of Muslim culture and the emergence of the Crimean Tatar national identity[citation needed]. The bilingual Crimean Tatar-Russian newspaper Terciman-Perevodchik he published in 1883-1914, functioned as an educational tool through which a national consciousness and modern thinking emerged among the entire Turkic-speaking population of the Russian Empire[citation needed]. His New Method (Usul-i Cedid) schools, numbered 350 across the Crimean peninsula helped create a new Crimean Tatar elite[citation needed]. After the Russian Revolution of 1917 this new elite, which included Noman Çelebicihan and Cafer Seydamet proclaimed the first democratic republic in the Islamic world, named the Crimean People's Republic on December 26, 1917. However, this republic was short-lived and destroyed by the Bolshevik uprising in January 1918[citation needed].

In the Soviet Union: 1917-1991

During Stalin's Great Purge, statesmen and intellectuals such as Veli Ibraimov and Bekir Çoban-zade (1893–1937), were imprisoned or executed on various charges.

Soviet collectivization of the peninsula led to widespread starvation in 1921. Food was confiscated for shipment to central Russia, while more than 100,000 Tatars starved to death, and tens of thousands fled to Turkey or Romania.[16] Thousands more were deported or slaughtered during the collectivization in 1928-29.[16] The government campaign led to another famine in 1931-33. No other Soviet nationality suffered the decline imposed on the Crimean Tatars; between 1917 and 1933 half the Crimean Tatar population had been killed or deported.[16]

During World War II, the entire Crimean Tatar population in Crimea fell victim to Soviet policies. Although a great number of Crimean Tatar men served in the Red Army and took part in the partisan movement in Crimea during the war, the existence of the Tatar Legion in the Nazi army and the collaboration of Crimean Tatar religious and political leaders with Hitler during the German occupation of Crimea provided the Soviets with a pretext for accusing the whole Crimean Tatar population of being Nazi collaborators. Modern researchers[who?] also point to the fact that a further reason was the geopolitical position of Crimea where Crimean Tatars were perceived as a threat. This belief is based in part on an analogy with numerous other cases of deportations of non-Russians from boundary territories (see, e.g., Involuntary settlements in the Soviet Union), as well as the fact that other non-Russian populations, such as Greeks, Armenians and Bulgarians were also been removed from Crimea[citation needed].

All Crimean Tatars were deported en masse, in a form of collective punishment, on 18 May 1944 as special settlers to Uzbek SSR and other distant parts of the Soviet Union.[17] The decree "On Crimean Tatars" describes the resettlement as a very humane procedure. The reality described by the victims in their memoirs was different. 46.3% of the resettled population died of diseases and malnutrition.[citation needed] This event is called Sürgün in the Crimean Tatar language. Many of them were re-located to toil as indentured workers in the Soviet GULAG system.[18]

Although a 1967 Soviet decree removed the charges against Crimean Tatars, the Soviet government did nothing to facilitate their resettlement in Crimea and to make reparations for lost lives and confiscated property. Crimean Tatars, differing from other Soviet nations like Ukrainians, having definite tradition of non-communist political dissent, succeeded in creating a truly independent network of activists, values and political experience.[19] Crimean Tatars, led by Crimean Tatar National Movement Organization,[20] were not allowed to return to Crimea from exile until the beginning of the Perestroika in the mid 1980s.

After Ukrainian independence

Today, more than 250,000 Crimean Tatars have returned to their homeland, struggling to re-establish their lives and reclaim their national and cultural rights against many social and economic obstacles. In 1991, the Crimean Tatar leadership founded the Qurultay, or Parliament, to act as a representative body for the Crimean Tatars which could address grievances to the Ukrainian central government, the Crimean government, and international bodies.[21] Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People is the executive body of the Qurultay.

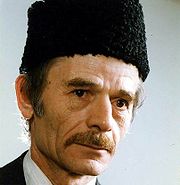

Since the 1990s, the political leader of the Crimean Tatars and the chairman of the Mejlis of the Crimean Tatar People is a former Soviet dissident Mustafa Abdülcemil Qırımoğlu.

See also

Part of a series on Crimean Tatars

By region or country Bulgaria · Romania · Turkey

United States · UzbekistanReligion Sunni Islam Languages and dialects Crimean Tatar · History Khanate (1441–1783)

Taurida Oblast (1783–1796)

Taurida Governorate (1802–1917)

People's Republic (1917–1918)

Crimean ASSR (1921–1945)

Sürgün (1944)

Crimean Oblast (1945–1991)

Autonomous Republic (since 1992)People and groups Famous Crimean Tatars

Khans · Mejlis · Milliy Firqa- Index of Crimean Tatars related articles

- Crimean Karaites

- Giray dynasty

- Baibars

- Krymchaks

- Lipka Tatars

- Mustafa Edige Kirimal

- Nogay

- Tatars

- Volga Tatars

References

- ^ AUTONOMOUS REPUBLIC OF CRIMEA: All-Ukrainian Population Census 2001 - National structure

- ^ All-Ukrainian Population Census 2001 - National structure

- ^ (Russian) Этноатлас Узбекистана

- ^ (Russian) О миграционном потенциале крымских татар из Узбекистана и др. к 2000 г.

- ^ (Russian) 1989 Soviet census - Uzbekistan

- ^ "Recensamant Romania 2002" (in Romanian). Agentia Nationala pentru Intreprinderi Mici si Mijlocii. 2002. http://mimmc.ro/info_util/formulare_1294/. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ^ (Russian) "Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года". Archived from the original on 2011-08-21. http://www.webcitation.org/616BvJEEv. Retrieved 2009-12-24.

- ^ Bulgaria Population census 2001

- ^ (Russian) Агентство Республики Казахстан по статистике. Перепись 2009. (Национальный состав населения.rar)

- ^ Halil İnalcik, 1942[page needed]

- ^ a b c "The Crimean Tatars and their Russian-Captive Slaves" (PDF). Eizo Matsuki, Mediterranean Studies Group at Hitotsubashi University.

- ^ Andrew G. Boston (18. April 2005). "Black Slaves, Arab Masters". Frontpage Magazine. http://www.frontpagemag.com/Articles/ReadArticle.asp?ID=17747. Retrieved 2011-01-08.

- ^ Alan Fisher, Muscovy and the Black Sea Slave Trade - Canadian American Slavic Studies, 1972, Vol. 6, pp. 575-594

- ^ a b c Alan W. Fisher, The Russian Annexation of the Crimea 1772-1783, Cambridge University Press, p. 26.

- ^ "Hijra and Forced Migration from Nineteenth-Century Russia to the Ottoman Empire", by Bryan Glynn Williams, Cahiers du Monde russe, 41/1, 2000, pp. 79-108.

- ^ a b c One Europe, many nations: a historical dictionary of European national groups, James Minahan, page 189, 2000

- ^ Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 483. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- ^ The Muzhik & the Commissar, TIME Magazine, November 30, 1953

- ^ Buttino, Marco (1993). In a Collapsing Empire: Underdevelopment, Ethnic Conflicts and Nationalisms in the Soviet Union, p.68 ISBN 88-07-99048-2

- ^ Abdulganiyev, Kurtmolla (2002). Institutional Development of the Crimean Tatar National Movement, ICC. Retrieved on 2008-03-22

- ^ Ziad, Waleed; Laryssa Chomiak (February 20 2007). "A Lesson in Stifling Violent Extremism: Crimea's Tatars have created a promising model to lessen ethnoreligious conflict". CS Monitor. http://www.csmonitor.com/2007/0220/p09s02-coop.html. Retrieved 2007-08-06.

Literature

- Conquest, Robert. 1970. The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities (London: Macmillan). (ISBN 0-333-10575-3)

- Fisher, Alan W. 1978. The Crimean Tatars. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. (ISBN 0-8179-6661-7)

- Fisher, Alan W. 1998. Between Russians, Ottomans and Turks: Crimea and Crimean Tatars (Istanbul: Isis Press, 1998). (ISBN 975-428-126-2)

- Nekrich, Alexander. 1978. The Punished Peoples: The Deportation and Fate of Soviet Minorities at the End of the Second World War (New Yk: W. W. Norton). (ISBN 0-393-00068-0)

- (Russian) Valery Vozgrin "Исторические судьбы крымских татар"

- Uehling, Greta (June 2000). "Squatting, self-immolation, and the repatriation of Crimean Tatars". Nationalities Papers 28 (2): 317–341. doi:10.1080/713687470.

External links

- Official web-site of Qirim Tatar Cultural Association of Canada

- Official web-site of Bizim QIRIM International Nongovernmental Organization

- International Committee for Crimea

- UNDP Crimea Integration and Development Programme

- Crimean Tatar Home Page

- Crimean Tatars

- Crimean Tatar words (Turkish)

- Crimean Tatar words (English)

- State Defense Committee Decree No. 5859ss: On Crimean Tatars (See also Three answers to the Decree No. 5859ss)

Crimea topics History Bosporan Kingdom · Scythia · Kipchaks · Goths · Khazars · Crimean campaigns · Crimean Khanate · Crimean War · Anti-NATO protests · morePolitics Religion History of Christianity · Moscow Patriarchate · Islam · Protestantism · Kiev Patriarchate · Roman Catholicism · Autocephalous (UAOC) · Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church · Judaism · moreAdministrative

divisionsGeography Economy Demographics Armenians in Crimea · Crimean Tatar language · Krymchak language · Crimean Tatars (List) · Krymchaks · Crimean Karaites · Crimean Germans · Crimean Goths · moreCulture and identity Majority CaucasianMinority Abkhazians · Bulgarian (Pomaks) · Georgians · Greek · Macedonian · Ossetians · Romanis

Categories:- Crimean Tatar people

- Ethnic groups in Ukraine

- Ethnic groups in Europe

- Indigenous peoples of Europe

- Turkic peoples

- Muslim communities

- Islam in Ukraine

- Muslim communities in Europe

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.