- Potash

-

For other uses, see Potash (disambiguation).

Potash /ˈpɒtæʃ/ is the common name for various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water-soluble form.[1] In some rare cases, potash can be formed with traces of organic materials such as plant remains, and this was the major historical source for it before the industrial era. The name derives from "pot ash," which refers to plant ashes soaked in water in a pot.

Today, potash is produced worldwide at amounts exceeding 30 million tonnes per year, mostly for use in fertilizers. Various types of fertilizer-potash thus comprise the single largest global industrial use of the element potassium. Potassium derives its name from potash, from which it was first derived by electrolysis of caustic potash, in 1808.

Contents

Terminology

Potash refers to potassium compounds and potassium-bearing materials, the most common being potassium chloride (KCl). The term "potash" comes from the Old Dutch word potaschen. The old method of making potassium carbonate (K2CO3) was by leaching of wood ashes and then evaporating the resulting solution in large iron pots, leaving a white residue called "pot ash". Approximately 10% by weight of common wood ash can be recovered as pot ash.[2][3] Later, "potash" became the term widely applied to naturally occurring potassium salts and the commercial product derived from them.[4]

The following table lists a number of potassium compounds which use the word potash in their traditional names:

Common name Chemical name Formula Potash fertilizer c.1942 potassium carbonate; c.1950 any one or more of potassium chloride, potassium sulfate (K2SO4), potassium magnesium sulfate (K2SO4·2MgSO4), langbeinite (K2Mg2(SO4)3) or potassium nitrate.[5][6] Does not contain potassium oxide, which plants do not take up.[7] Caustic potash or potash lye potassium hydroxide KOH Carbonate of potash, salts of tartar, or pearlash potassium carbonate K2CO3 Chlorate of potash potassium chlorate KClO3 Muriate of potash potassium chloride KCl:NaCl (95:5 or higher)[1] Nitrate of potash or saltpeter potassium nitrate KNO3 Sulfate of potash potassium sulfate K2SO4 Permanganate of potash potassium permanganate KMnO4 History of production

Potash (especially potassium carbonate) has been used from the dawn of history in bleaching textiles, making glass, and, from about A.D. 500, in making soap. Potash was principally obtained by leaching the ashes of land and sea plants. Beginning in the 14th century potash was mined in Ethiopia. One of the world's largest deposits, 140 to 150 million tons, is located in the Tigray's Dallol area.[8] Potash was one of the most important industrial chemicals in Canada. It was refined from the ashes of broadleaved trees and produced primarily in the forested areas of Europe, Russia, and North America. The first U.S. patent was issued in 1790 to Samuel Hopkins for an improvement "in the making Pot ash and Pearl ash by a new Apparatus and Process."[9]

As early as 1767, potash from wood ashes was exported from Canada, and exports of potash and pearl ash (potash and lime) reached 43,958 barrels in 1865. There were 519 asheries in operation in 1871. The industry declined in the late 19th century when large-scale production of potash from mineral salts was established in Germany. In 1943, potash was discovered in Saskatchewan, Canada, in the process of drilling for oil. Active exploration began in 1951. In 1958, the Potash Company of America became the first potash producer in Canada with the commissioning of an underground potash mine at Patience Lake; however, due to water seepage in its shaft, production stopped late in 1959 and, following extensive grouting and repairs, resumed in 1965. The underground mine was flooded in 1987 and was reactivated for commercial production as a solution mine in 1989.[3]

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, potash production provided settlers in North America a way to obtain badly-needed cash and credit as they cleared wooded land for crops. To make full use of their land, settlers needed to dispose of excess wood. The easiest way to accomplish this was to burn any wood not needed for fuel or construction. Ashes from hardwood trees could then be used to make lye, which could either be used to make soap or boiled down to produce valuable potash. Hardwood could generate ashes at the rate of 60 to 100 bushels per acre (500 to 900 m3/km2). In 1790, ashes could be sold for $3.25 to $6.25 per acre ($800 to $1500/km2) in rural New York State – nearly the same rate as hiring a laborer to clear the same area. Potash making became a major industry in British North America. Great Britain was always the most important market. The American potash industry followed the woodsman's ax across the country. After about 1820, New York replaced New England as the most important source; by 1840 the center was in Ohio. Potash production was always a by-product industry, following from the need to clear land for agriculture.[10]

Most of the world reserves of potassium (K) were deposited as sea water in ancient inland oceans evaporated, and the potassium salts crystallized into beds of potash ore. These are the locations where potash is currently being mined today. The deposits are a naturally-occurring mixture of potassium chloride (KCl) and sodium chloride (NaCl), better known as common table salt. Over time, as the surface of the earth changed, these deposits were covered by thousands of feet of earth.[10]

Most potash mines today are deep shaft mines as much as 4,400 feet (1,400 m) underground. Others are mined as strip mines, having been laid down in horizontal layers as sedimentary rock. In above-ground processing plants, the KCl is separated from the mixture to produce a high analysis natural potassium fertilizer. Other naturally occurring potassium salts can be separated by various procedures, resulting in potassium sulfate and potassium-magnesium sulfate.

Today some of the world's largest known potash deposits are spread all over the world from Saskatchewan, Canada, to Brazil, Belarus, Germany, and more notably the Permian Basin. The Permian basin deposit includes the major mines outside of Carlsbad, New Mexico, to the world's purest potash deposit in Lea County New Mexico (not far from the Carlsbad deposits), which is believed to be roughly 80% pure. Canada is the largest producer, followed by Russia and Belorussia. The most significant reserve of Canada's potash is located in the province of Saskatchewan and controlled by the Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan.[1]

In the beginning of the 20th century, potash deposits were found in the Dallol Depression in Musely and Crescent localities near the Ethiopean-Eritrean border. The estimated reserves are 173 and 12 million tonnes for the Musely and Crescent, respectively. The latter is particularly suitable for surface mining; it was explored in the 1960s but the works stopped due to the flood in 1967. Attempts to continue mining in the 1990s were halted by the Eritrean–Ethiopian War and have not resumed by 2009.[11]

Consumption

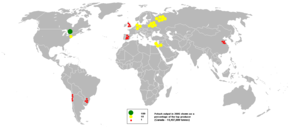

Production and resources of potash

(2010, in million tonnes)[12]Country Production Reserves  Canada

Canada9.5 4400  Russia

Russia6.8 3300  Belarus

Belarus5.0 750  China

China3.0 210  Germany

Germany3.0 150  Israel

Israel2.1 40  Jordan

Jordan1.2 40  United States

United States0.9 130  Chile

Chile0.7 70  Brazil

Brazil0.4 300  United Kingdom

United Kingdom0.4 22  Spain

Spain0.4 20 Other countries 50 World total 33 9500 Fertilizers

Potassium is the seventh most abundant element in the Earth's crust, and is the third major plant and crop nutrient after nitrogen and phosphorus. It has been used since antiquity as a soil fertilizer (about 90% of current use).[2] Potash is important for agriculture because it improves water retention, yield, nutrient value, taste, colour, texture and disease resistance of food crops. It has wide application to fruit and vegetables, rice, wheat and other grains, sugar, corn, soybeans, palm oil and cotton, all of which benefit from the nutrient’s quality enhancing properties.[13]

Demand for food and animal feed has been on the rise since 2000. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service (ERS) attributes the trend to average annual population increases of 75 million people around the world. Geographically, economic growth in Asia and Latin America greatly contributed to the increased use of potash-based fertilizer. Rising incomes in developing countries also was a factor in the growing potash and fertilizer use. With more money in the household budget, consumers added more meat and dairy products to their diets. This shift in eating patterns required more acres to be planted, more fertilizer to be applied and more animals to be fed – all requiring more potash.

After years of trending upward, fertilizer use slowed in 2008. The worldwide economic downturn is the primary reason for the declining fertilizer use, dropping prices and mounting inventories.[14][15]

The world's largest consumers of potash are China, the United States, Brazil and India.[16] Brazil imports 90% of the potash it needs.[16][9]

Potash imports and exports are often reported in "K2O equivalent", although fertilizer never contains potassium oxide, per se, because potassium oxide is caustic and hygroscopic.

Potash prices have soared in recent years. What was once a commodity worth about $200 a tonne is expected to reach $1,500 by 2020; Vancouver prices are US$872.50 per tonne in 2009, which is a record high.[17] As of November 2011 potash prices have dropped to about $470 per metric tonne.[18]

Other uses

In addition to its use as a fertilizer, potassium chloride is important in industrialized economies, where it is used in aluminium recycling, by the chloralkali industry to produce potassium hydroxide, in metal electroplating, oil-well drilling fluid, snow and ice melting, steel heat-treating, and water softening. Potassium hydroxide is used for industrial water treatment and is the precursor of potassium carbonate, several forms of potassium phosphate, many other potassic chemicals, and soap manufacturing. Potassium carbonate is used to produce animal feed supplements, cement, fire extinguishers, food products, photographic chemicals, and textiles. It is also used in brewing beer, pharmaceutical preparations, and as a catalyst for synthetic rubber manufacturing. These nonfertilizer uses have accounted for about 15% of annual potash consumption in the United States.[1]

Potash (potassium carbonate) along with hartshorn was also used as a baking aid similar to baking soda in old German baked goods such as lebkuchen (ginger bread).[19]

References

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Geological Survey document "Potash".

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Geological Survey document "Potash".- ^ a b c d Potash, USGS 2008 Minerals Yearbook

- ^ a b Stephen M. Jasinski. "Potash". USGS. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/potash/.

- ^ a b "Potash". The Canadian Encyclopedia. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0006428.

- ^ "The World Potash Industry: Past, Present and Future". New Orleans, LA: 50th Anniversary Meeting The Fertilizer Industry Round Table. 2000. http://www.potashcorp.com/media/pdf/investor_relations/speeches/world_potash_industry.pdf.

- ^ Dennis Kostick (September 2006). "Potash" (PDF). 2005 Minerals Handbook. United States Geological Survey. p. 58.1. http://minerals.usgs.gov/minerals/pubs/commodity/potash/potasmyb05.pdf. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- ^ J. W. Turrentine (1934). "Composition of Potash Fertilizer Salts for Sale on the American Market". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry (American Chemical Society) 26 (11): 1224–1225.

- ^ Joseph R. Heckman (January 17, 2002). Plant & Pest Advisory. 7. Rutgers University. p. 3. http://njaes.rutgers.edu/pubs/plantandpestadvisory/2002/fc0117.pdf.

- ^ Ethiopia Mining

- ^ a b Kids – Time Machine – Historic Press Releases – USPTO

- ^ a b Fite, Robert C Origin and occurrence of commercial potash deposits, Academy of Sciences for 1951

- ^ "Minerals for Agricultural Industrialization". Ministry of Mines and Energy of Ethiopia. http://www.mome.gov.et/industrial.html.

- ^ Stephen M. Jasinski Potash, USGS Mineral Commodity Summary 2011

- ^ Potash Price Close to all time highs – Future Outlook

- ^ Potash Around the World

- ^ "Potash global review: tunnel vision", Industrial Minerals, May 2009

- ^ a b Supply and Demand

- ^ "Potash prices are record high". Potash Investing news. February 5, 2009. http://www.potashinvestingnews.com/354-potash-prices-at-record-high.html.

- ^ http://www.infomine.com/chartsanddata/chartbuilder.aspx?z=f&g=127651&dr=2y

- ^ Cameron French (June 14, 2008). "Potash: The new gold rush". Globe and Mail. http://www.reportonbusiness.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20080613.wpotash0613/BNStory/energy/home?cid=al_gam_mostemail. Retrieved 2008-06-01.

Further reading

- Seaver, Frederick J (1918) "Historical Sketches of Franklin County And Its Several Towns", J.B Lyons Company, Albany, NY, Section "Making Potash" pp. 27–29

External links

- They Burned The Woods and Sold the Ashes

- Henry M. Paynter, The First Patent, Invention & Technology, Fall 1990

- The First U.S. Patent, issued for a method of potash production

- World Agriculture and Fertilizer Markets Map

- "Digging for Potash, Mining Companies Encounter An Iron Will" magazine article

- Russia reaps rich harvest with potash

Categories:- Agricultural chemicals

- Fertilizers

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.