- Axis occupation of Greece during World War II

-

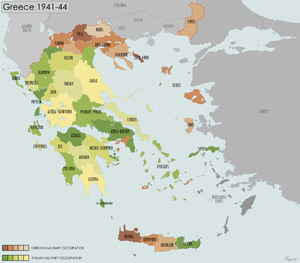

The Axis occupation of Greece during World War II (Greek: Η Κατοχή, I Katochi, meaning "The Occupation") began in April 1941 after the German and Italian invasion of Greece. The occupation lasted until the German withdrawal from the mainland in October 1944. In some cases however, such as in Crete and other islands, German garrisons remained in control until May and June 1945.

Fascist Italy had initially invaded Greece in October 1940 but was defeated, and the Greek Army pushed the invaders back into neighbouring Albania. This forced Germany to shift its military focus from the preparation of "Operation Barbarossa" to an intervention on its ally's behalf in southern Europe. A rapid German Blitzkrieg campaign followed in April 1941, and by the middle of May, Greece was occupied by the Nazis who proceeded to administer the most important regions themselves, including Athens and Thessaloniki. Other regions of the country were given to Germany's lesser partners, Fascist Italy and Bulgaria. A collaborationist Greek government was established immediately after the country fell.

The occupation brought about terrible hardships for the Greek civilian population. Over 300,000 civilians died in Athens alone from starvation, tens of thousands more through reprisals by Nazis and collaborators, and the country's economy was ruined.[1] At the same time the Greek Resistance, one of the most effective resistance movements in Occupied Europe, was formed. These resistance groups launched guerrilla attacks against the occupying powers, fought against the collaborationist Security Battalions and set up large espionage networks, but by late 1943 began to fight amongst themselves. When liberation came in October 1944, Greece was in a state of extreme political polarization, which soon led to the outbreak of civil war. The subsequent civil war gave the opportunity to many prominent Nazi collaborators not only to escape punishment (because of their anti-communism), but to eventually become the ruling class of postwar Greece, after the communist defeat.[2][3]

Contents

Fall of Greece

See also: Greco-Italian War, Battle of Greece, Battle of Crete, and Military history of Greece during World War II German artillery shelling the Metaxas Line.

German artillery shelling the Metaxas Line.

German soldiers raising the German War Flag over the Acropolis. It would be taken down by Manolis Glezos and Apostolos Santas in one of the first acts of resistance.

German soldiers raising the German War Flag over the Acropolis. It would be taken down by Manolis Glezos and Apostolos Santas in one of the first acts of resistance.

In the early morning hours of 28 October 1940, Italian Ambassador Emmanuel Grazzi awoke Greek Premier Ioannis Metaxas and presented him an ultimatum. Metaxas rejected the ultimatum and Italian forces invaded Greek territory from Italian-occupied Albania less than three hours later. (The anniversary of Greece's refusal is now a public holiday in Greece.) Mussolini launched the invasion partly to prove that Italians could match the military successes of the German Army and partly because Mussolini regarded southeastern Europe as lying within Italy's sphere of influence.

The Greek army proved to be a formidable opponent, and successfully exploited the mountainous terrain of Epirus. The Greek forces counterattacked and forced the Italians to retreat. By mid-December, the Greeks had occupied nearly one-quarter of Albania, before Italian reinforcements and the harsh winter stemmed the Greek advance. In March 1941, a major Italian counterattack partially failed and the Italian troops only reoccupied small areas around Himare and Grabova. The initial Greek defeat of the Italian invasion is considered the first Allied land victory of the Second World War, even if in the event the campaign, thanks mainly to the German intervention, resulted in a victory for the Axis.

Fifteen of the twenty one Greek divisions were deployed against the Italians, so only six divisions were facing the attack from German troops in the Metaxas Line (near the border between Greece and Yugoslavia/Bulgaria) during the first days of April. In those days, Greece received help from British Commonwealth troops, moved from Libya by orders of Churchill.

On 6 April 1941, Germany came to the aid of Italy and invaded Greece through Bulgaria and Yugoslavia. Greek and British Commonwealth troops fought back but were overwhelmed.

On April 20, after Greek resistance in the north had ceased, the Bulgarian Army entered Greek Thrace, without having fired a shot,[4] with the goal of regaining its Aegean Sea outlet in Western Thrace and Eastern Macedonia. The Bulgarians occupied territory between the Strymon River and a line of demarcation running through Alexandroupoli and Svilengrad west of the Evros River.

The Greek capital Athens fell on 27 April, and by 1 June, after the capture of Crete, all of Greece was under Axis occupation.

The Triple Occupation

The occupation of Greece was divided between Germany, Italy and Bulgaria. German forces occupied the most strategically important areas, namely Athens, Thessaloniki with Central Macedonia and several Aegean Islands, including most of Crete. East Macedonia and Thrace came under Bulgarian occupation and was annexed to Bulgaria, which had long claimed these territories. The remaining two thirds of Greece was occupied by Italy, with the Ionian Islands directly administered as Italian territories. After the Italian capitulation in September 1943, the Italian zone was taken over by the Germans, often accompanied by violence towards the Italian garrisons. There was a failed attempt by the British to take advantage of the Italian surrender to reenter the Aegean, resulting in the Dodecanese Campaign.

The German occupation zone

Economic exploitation and the Great Famine

Main article: Great Famine German Panzer IV Ausf. G in Athens (1943).

German Panzer IV Ausf. G in Athens (1943).

Greece suffered greatly during the occupation.[5][6] The country's economy had already been devastated from the 6-month long war, and to it was added the relentless economic exploitation by the Nazis.[7] Raw materials and foodstuffs were requisitioned, and the collaborationist government was forced to pay the cost of the occupation, giving rise to inflation, further exacerbated by a "war loan" which was never paid back,Greece was forced to grant to the German Reich which severely devalued the Drachma. Requisitions, together with the Allied blockade of Greece, the ruined state of the country's infrastructure and the emergence of a powerful and well-connected black market, resulted in the Great Famine during the winter of 1941-42 (Greek: Μεγάλος Λιμός), when an estimated 300,000 people perished in greater Athens.[8] Despite aid from neutral countries like Sweden and Turkey (see SS Kurtuluş), the overwhelming majority of foodstuff ended up in the hands of the government officials and black market traders who used their connection to the Axis Occupation authorities to "buy" the aid from them and then sell it on to the desperate population at enormously inflated prices. The great suffering and the pressure of the exiled Greek government eventually forced the British to partially lift the blockade, and from the summer of 1942, the International Red Cross was able to distribute supplies in sufficient quantities.[9]

Nazi atrocities

Sign in German and Greek erected at the village of Kandanos in Crete, which was wholly destroyed by the Germans as reprisal for a partisan attack. The German portion of the sign reads: "Kandanos was destroyed in retaliation for the bestial ambush murder of a paratrooper platoon and a half-platoon of military engineers by armed men and women."

Sign in German and Greek erected at the village of Kandanos in Crete, which was wholly destroyed by the Germans as reprisal for a partisan attack. The German portion of the sign reads: "Kandanos was destroyed in retaliation for the bestial ambush murder of a paratrooper platoon and a half-platoon of military engineers by armed men and women."

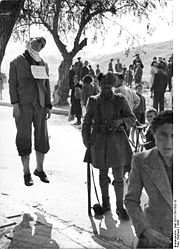

Increasing attacks by partisans in the latter years of the occupation resulted in a number of executions and wholesale slaughter of civilians in reprisal. In total, the Germans executed some 21,000 Greeks, the Bulgarians 40,000 and the Italians 9,000.[10]

The most imfamous examples in the German zone are those of the village of Kommeno on 16 August 1943, where 317 inhabitants were executed by the 1. Gebirgs-Division and the village torched, the "Holocaust of Viannos" on 14–16 September 1943, in which over 500 civilians from several villages in the region of Viannos and Ierapetra in Crete were executed by the 22. Luftlande Infanterie-Division, the "Massacre of Kalavryta" on 13 December 1943, in which Wehrmacht troops of the 117th Jäger Division carried out the extermination of the entire male population and the subsequent total destruction of the town, the "Distomo massacre" on 10 June 1944, where an SS Police unit looted and burned the village of Distomo in Boeotia resulting in the deaths of 218 civilians and the "Holocaust of Kedros" on 22 August 1944 in Crete, where 164 civilians were executed and nine villages were dynamited after being looted. At the same time, in the course of the concerted anti-guerrilla campaign, hundreds of villages were systematically torched and almost 1,000,000 Greeks left homeless.[1]

Two other notable acts of brutality were the massacres of Italian troops at the islands of Cephallonia and Kos in September 1943, during the German takeover of the Italian occupation areas. In Cephallonia, the 12,000-strong Italian Acqui Division was attacked on September 13 by elements of 1.Gebirgs-Division with support from Stukas, and forced to surrender on September 21, after suffering some 1,300 casualties. The next day, the Germans began executing their prisoners and did not stop until over 4,500 Italians had been shot. The 4,000 or so survivors were put aboard ships for the mainland, but some of them sank after hitting mines in the Ionian Sea, where another 3,000 were lost.[11] The Cephallonia massacre serves as the background for the novel Captain Corelli's Mandolin.[12][13]

The Italian occupation zone

The Italians occupied the bulk of the Greek mainland and most of the islands. Although several proposals for territorial annexation had been put forward in Rome, none was actually carried out during the war. This was due to pressure from the King of Italy, Victor Emmanuel III, and from the Germans, who were concerned of further alienating the Greek population, which was already strongly opposing the Bulgarian annexations.

Nevertheless, in the Ionian Islands, long a target of Italian expansionism, as well as in the Cyclades, the Greek civil authorities were replaced by Italians in preparation for a post-war annexation. In Epirus, the area near the Albanian border, where a significant Albanian minority (the Cham Albanians) existed, was claimed by Albanian irredentists as Chameria. Before the war, a great part of Italian propaganda against Greece had revolved around the Chameria issue, as the Italians hoped to gain Albanian support by promoting irredentism in Chameria and Kosovo.[14] Although the Italians wanted to annex Chameria to Albania, the Germans vetoed the proposal. An Albanian High Commissioner, Xhemil Dino, was appointed, but his authority was limited, and for the duration of the Occupation, the area remained under direct control from the military authorities in Athens.[15]

Another case of Italian-sponsored minority states on Greek territory were the Aromanian Principality of the Pindus and the Grand Voivodeship of Macedonia, statelets that were to encompass the regions of West Macedonia, northern Thessaly and Epirus,[16] and headed by Alchiviad Diamandi, Nicolau Matoussi and Count Gyula Cseszneky. The bulk of the Aromanian population however refused to collaborate, and the "principality" never amounted to much beyond Diamandi's followers, the so-called "Roman Legion".[17] With the growth of the Resistance in 1943 and the collapse of their Italian sponsors in September 1943, the plans for the Principality were conclusively shelved.

Compared to the other two zones, the Italian occupation regime was relatively mild. Unlike the Germans, and aside from some local commanders, the Italian military never implemented a policy of mass reprisals and protected the Jews in their zone. As they controlled most of the countryside, the Italians were the first to face the rising resistance movement in 1942-43, but failed to contain it. By mid-1943, the Resistance had managed to expel the Italian garrisons from some mountainous areas, including several towns, creating liberated zones ("Free Greece"). After the Italian armistice in September 1943, the Italian zone was taken over by the Germans. As a result, German anti-partisan and anti-Semitic policies were extended to it.

The Bulgarian occupation zone

The Bulgarian Army entered Greece on 20 April 1941 on the heels of the Wehrmacht without having fired a shot[18] and eventually occupied the whole of northeastern Greece eastern Macedonia and Western Thrace), except for the Evros prefecture, at the border with Turkey, which was occupied by the Germans. Unlike Germany and Italy, Bulgaria officially annexed the occupied territories, which had long been a target of Bulgarian irredentism, on 14 May 1941.[19]

The Greeks never thought highly of the Bulgarians, considering them uncultured barbarians.[20][21][22] As a result, there was immediate resentment, especially since the Bulgarians did not win these regions militarily.

Throughout the Bulgarian zone, Bulgarian policy was that of extermination or expulsion,[23] aiming to forcibly Bulgarize as many Greeks as possible and expel or kill the rest.[24] A massive campaign was launched right from the start, which saw all Greek officials (mayors, judges, lawyers and gendarmes) deported. The Bulgarians closed the Greek schools and expelled the teachers, replaced Greek clergymen with priests from Bulgaria, and sharply repressed the use of the Greek language: the names of towns and places changed to the forms traditional in Bulgarian,[19] and even gravestones bearing Greek inscriptions were defaced.[25]

Large numbers of Greeks were expelled and others were deprived of the right to work by a license system that banned the practice of a trade or profession without permission. Forced labour was introduced, and the authorities confiscated the Greek business property and gave it to Bulgarian colonists.[24] By late 1941, more than 100,000 Greeks had been expelled from the Bulgarian occupation zone.[26][27] Bulgarian colonists were encouraged to settle in Macedonia by government credits and incentives, including houses and land confiscated from the natives.

Bulgarian propaganda tried to win the loyalty of the Slavic-speakers, while some of them did greet the Bulgarians as liberators. This campaign was less successful in German held Western Macedonia.[28] At that time most of them felt themselves to be Bulgarians.[29] The German High Command approved the foundation of a Bulgarian military club in Thessaloníki.[citation needed] The Bulgarian organized suppling of food and provisions for the Slavic-speaking population in Greek Macedonia, aiming to gain the local population that was in the German and Italian occupied zones. The Bulgarian clubs soon started to gain support among parts of that population.[citation needed] In 1942, the Bulgarian club asked assistance from the High command in organizing armed units among the Slavic-speaking population in northern Greece. For this purpose, the Bulgarian army sent a handful of officers from the Bulgarian Army, to the zones occupied by the Italian and German troops. These officers were given the objective to form armed Slavophone militias - Ohrana, which initial detachments were formed in 1943 in the district of Kastoria, Edessa and Florina.[citation needed]

The Drama uprising

In this situation, a revolt broke out on 28 September 1941. It started from the city of Drama and quickly spread throughout Macedonia. In Drama, Doxato, Choristi and many other towns and villages clashes broke out with the occupying forces. On 29 September, Bulgarian troops moved into Drama and the other rebellious cities to suppress the uprising. They seized all men between 18 and 45, executed over three thousand people in Drama alone. An estimated 15,000 Greeks were killed from the Bulgarian occupational army during the next few weeks and in the countryside entire villages were machine gunned and looted.[24]

The massacres precipitated a mass exodus of Greeks from the Bulgarian into the German occupation zone. Bulgarian reprisals continued after the September revolt, adding to the torrent of refugees. Villages were destroyed for sheltering “partisans” who were in fact only the survivors of villages previously destroyed. The terror and famine became so severe that the Athens government considered plans for evacuating the entire population to German-occupied Greece.[30] The widespread winter famine of 1941, that killed hundreds of thousands in the occupied country canceled these plans, leaving the population to endure those conditions for another three years. In May 1943 deportation of Jews from the Bulgarian occupation zone began as well.[31] In the same year the Bulgarian army expanded its zone of control into Central Macedonia under German supervision, although this area was not formally annexed nor administered by Bulgaria.

Civil Administration

For the purposes of civil administration before the invasion, Greece was divided into 37 prefectures. Following the occupation, the prefectures of Drama, Kavalla, Rhodope and Serres were annexed by Bulgaria and were no longer under the control of the Greek government. The remaining 33 prefectures had a concurrent military administration by Italian or German troops. The Italian-occupied Cyclades and the Ionian Islands were mostly detached from the Greek mainland and placed under effective Italian administration, although some administrative links to the Athens government were retained. In 1943, Attica and Boeotia was split into separate prefectures.

Prefectures 1941–43

- Achaea

- Aetolia-Acarnania

- Arcadia

- Argolis-Corinthia

- Arta

- Attica-Boeotia

- Chalkidiki

- Chania

- Chios

- Corfu

- Cyclades

- Elis

- Evros

- Florina

- Heraklion

- Ioannina

- Kefalonia

- Kilkis

- Kozani

- Laconia

- Larisa

- Lasithi

- Lesbos

- Messenia

- Pella

- Phthiotis-Phocis

- Preveza

- Rethymno

- Samos

- Thesprotia

- Thessaloniki

- Trikala

- Zakynthos

Prefectures annexed by Bulgaria

Collaboration

Main article: Hellenic State (1941-1944) Execution of suspected resistance members by the Security Battalions.

Execution of suspected resistance members by the Security Battalions.

General Georgios Tsolakoglou — who had signed the armistice treaty with the Wehrmacht — was appointed as chief of a new Nazi puppet collaborationist regime in Athens. He was succeeded as Prime Minister of Greece by two other prominent Greek collaborators: Konstantinos Logothetopoulos first, and Ioannis Rallis second. The latter was responsible for the creation of the Greek collaborationist Security Battalions. As in other European countries, there were Greeks willing to collaborate with the occupying force. Some did so because they shared the National Socialist ideology, others because of extreme anti-Communism, and others because of opportunistic advancement. The Germans were also eager to find support from and helped Greek fascist organizations such as the EEE (Ethniki Enosis Ellados), the EKK (Ethnikon Kyriarchon Kratos), the Greek National Socialist Party (Elliniko Ethnikososialistiko Komma, EEK) led by George S. Mercouris and other minor pro-Nazi, fascist or anti-Semitic organizations such as the ESPO (Hellenic Socialist Patriotic Organization) or the Sidira Eirini ("Iron Peace").

Among the minority populations of Greece, many Cham Albanians actively collaborated with the Axis occupation forces in Thesprotia.[32][33] Due to this activity, they fled from the country when the war ended.[33] In Macedonia the Slavic minority formed various paramilitary units like the Ohrana and collaborated extensively with the Bulgarian occupation forces in their attempt to ethnically cleanse their areas of occupation from Greeks.

Resistance

Main article: Greek ResistanceHowever, few Greeks cooperated with the Nazis and most chose either the path of passive acceptance or active resistance. Active Greek resistance started immediately as many Greeks fled to the hills, where a partisan movement was born. One of the most touching episodes of the early resistance took place just after the Wehrmacht reached the Acropolis on 27 April. The Germans ordered the flag guard, Evzone Konstandinos Koukidis, to retire the Greek flag. The Greek soldier obeyed, but when he was done, he wrapped himself in the flag and threw himself off of the plateau where he met death. Some days later, when the Reichskriegsflagge was waving on the Acropolis' uppermost spot, two patriotic Athenian youngsters, Manolis Glezos and Apostolos Santas climbed by night on the Acropolis and tore down the flag. It was one of the first actions of Greek resistance and among the first in Europe, and therefore inspired not only Greeks but also other Europeans under German domination.

The first signs of armed resistance activity manifested themselves in northern Greece, where resentment at the Bulgarian annexations ran high, in early autumn 1941. The Germans responded swiftly, torching several villages and executing 488 civilians. The brutality of these reprisals did indeed lead to a collapse of the early guerrilla movement, until it was revived in 1942 at a much greater scale.[34] The greatest source of partisan activity were the Communist-backed guerrilla forces, the National Liberation Front (EAM), and its military wing, the National People's Liberation Army (ELAS), which carried out operations of sabotage and guerrilla attacks against the Wehrmacht with notable success. Other resistance groups included a right-wing partisan organization, the National Republican Greek League (EDES), led by Colonel Napoleon Zervas, a former army officer and well-known Republican, and the National and Social Liberation (EKKA), led by Colonel Dimitrios Psarros, a Royalist. These groups were formed from remnants of the Hellenic Army and the conservative factions of Greek society. Starting in 1943, on a number of cases EDES and ELAS fought each other in a sort of prelude to the civil war that sprang up after the German departure in 1944. EAM alleged that EDES was aided by the German occupying forces and by the Nazi-supported puppet regimes of Tsolakoglou, Logothetopoulos and Rallis. This situation led to triangular battles among ELAS, EDES and the Germans. At the same time, ELAS attacked and destroyed Psarros' military formation, the "5/42 Evzones Regiment", killing him.

When Italy surrendered to the Allies in the autumn of 1943, German forces actively hunted down and, in some cases executed, the Italian soldiers, including at least 5000 in the Massacre of the Acqui Division. They simultaneously began serious attacks on EDES. There is evidence that Zervas then struck a deal with the German Army and agreed not to attack each other. This truce left the Germans free of sabotage in some areas and allowed EDES to face ELAS. The EDES-German truce ended in 1944, when the Germans began evacuating Greece and the British agents in Greece negotiated a ceasefire (the Plaka agreement).[35] Accusations from EDES against ELAS referred to collaboration with Bulgarians in eastern Macedonia, the case of MAVI and the cruelty and murders against non communists.

The stage, however, was already set for the next period of Greek history: the Greek Civil War.

Liberation and aftermath

See also: Greek Civil WarGerman forces began withdrawing from the Greek mainland in late 1944 as Soviet forces advancing into South-Eastern Europe from the Ukraine threatened to cut them off. Greece was one of the few European countries to gain territory from the Second World War when the formerly Italian Dodecanese became part of Greece in 1947.

The Holocaust in Greece

See also: History of the Jews in Greece A young woman weeps during the deportation of the Jews of Ioannina on March 25, 1944. Almost all of the people deported were murdered on or shortly after April 11, 1944, when the train carrying them reached Auschwitz-Birkenau.[36][37]

A young woman weeps during the deportation of the Jews of Ioannina on March 25, 1944. Almost all of the people deported were murdered on or shortly after April 11, 1944, when the train carrying them reached Auschwitz-Birkenau.[36][37]

Registration of the male Jews by Nazis at the center of Thessaloniki (Eleftherias square), July 1942.

Registration of the male Jews by Nazis at the center of Thessaloniki (Eleftherias square), July 1942.

Prior to World War II, there existed two main groups of Jews in Greece: the scattered Romaniote communities which had existed in Greece since antiquity; and the approximately 50,000-strong Sephardi Jewish community of Thessaloniki, originally formed from Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition in the Middle Ages. The latter had played a prominent part in the city's life for five centuries, but as the city had only become a part of the modern Greek state during the First Balkan War, it was not as well-integrated.

When the occupation zones were drawn up, Thessaloniki passed under German control. Thrace passed under Bulgarian control. Despite initial assurances to the contrary, the Nazis and Bulgarians gradually imposed a series of anti-Jewish measures. Jewish newspapers were closed down, local anti-Semites were encouraged to post anti-Jewish notices around the cities, Jews in the German and Bulgarian zones were forced to wear the Star of David so they could be easily identified and further isolated from the rest of the Greeks. Jewish families were kicked out of their homes and arrested while the Nazi-controlled press turned public opinion against them. By December 1942, the Germans began to demolish the old Jewish cemetery in Thessaloniki so the ancient tombstones could used as building material for sidewalks and walls.[38] The site of the old cemetery is today occupied by the campus of the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.[39]

Despite warnings of impending deportations, most Jews were reluctant to leave their homes, although several hundred were able to flee the city. The Germans and Bulgarians began mass deportations in March 1943, sending the Jews of Thessaloniki and Thrace in packed boxcars to the distant Auschwitz and Treblinka death camps. By the summer of 1943, the Jews of the German and Bulgarian zones were gone and only those in the Italian zone remained. Jewish property in Thessaloniki was distributed to Greek 'caretakers' who were chosen by special committee, the "Service for the Disposal of Jewish Property" (YDIP). Instead of giving apartments and businesses to the many refugees, however, they were most often given to friends and relatives of committee members or collaborators.[40]

In September 1943, after the Italian collapse, the Germans turned their attention to the Jews of Athens and the rest of formerly Italian-occupied Greece. There their propaganda was not as effective, as the ancient Romaniote Jewish communities were well-integrated into the Orthodox Greek society and could not easily be singled out from the Christians, who in turn were more ready to resist the German authorities' demands. The Archbishop of Athens Damaskinos ordered his priests to ask their congregations to help the Jews and sent a strong-worded letter of protest to the collaborationist authorities and the Germans. Many Orthodox Christians risked their lives hiding Jews in their apartments and homes, despite threat of imprisonment. Even the Greek police ignored instructions to turn over Jews to the Germans. When Jewish community leaders appealed to Prime Minister Ioannis Rallis, he tried to alleviate their fears by saying that the Jews of Thessaloniki had been guilty of subversive activities and that this was the reason they were deported. At the same time, Elias Barzilai, the Grand Rabbi of Athens, was summoned to the Department of Jewish Affairs and told to submit a list of names and addresses of members of the Jewish community. Instead he destroyed the community records, thus saving the lives of thousands of Athenian Jews. He advised the Jews of Athens to flee or go into hiding. A few days later, the Rabbi himself was spirited out of the city by EAM-ELAS fighters and joined the resistance. EAM-ELAS helped hundreds of Jews escape and survive, many of whom stayed with the resistance as fighters and/or interpreters.

In total, at least 81% (ca. 60,000) of Greece's total pre-war Jewish population perished, with the percentage ranging from Thessaloniki's 91% to 'just' 50% in Athens, or even less in other provincial areas such as Volos (36%). In the Bulgarian zone, death rates surpassed 90%.[41] In the notable case of the Ionian island of Zakynthos, all 275 Jews survived, being hidden in the island's interior.[42]

Influence in post-war culture

The Axis occupation of Greece, specifically the Greek islands, has a significant presence in English-language books and films. Real special forces raids e.g. Ill Met by Moonlight or fictional special forces raids The Guns of Navarone, Escape to Athena and They Who Dare (1954) or the fictional occupation narrative Captain Corelli's Mandolin are eminent examples.

Notable personalities of the occupation

Greek collaborators:

- Lt General Georgios Tsolakoglou, Prime Minister 1941-42

- Konstantinos Logothetopoulos, Prime Minister 1942-43

- Ioannis Rallis, Prime Minister 1943-44

- Sotirios Gotzamanis, Finance Minister 1941-43

- Major General Georgios Bakos, Army Minister 1941-43

- Colonel Ioannis Plytzanopoulos, head of the Security Battalions

- Colonel Georgios Poulos, SS collaborator

Greek Resistance leaders:

- Aris Velouchiotis, chief ELAS captain

- Napoleon Zervas, military leader of EDES

- Dimitrios Psarros, military leader of EKKA

- General Stefanos Sarafis, military commander of ELAS

- Georgios Siantos, political leader of EAM

- Markos Vafiades, senior ELAS captain in Macedonia

- Evripidis Bakirtzis, head of the PEEA

- Komninos Pyromaglou, political leader of EDES

- Georgios Kartalis, political leader of EKKA

Other Greek personalities

- Angelos Evert, Athens City Police Chief

- Damaskinos, Archbishop of Athens

- Manolis Glezos and Apostolos Santas

- Elias Degiannis

- George Psychoundakis, Cretan partisan

German officials:

- Ambassador Günther Altenburg, German Plenipotentiary

- Hermann Neubacher, Reich Special Envoy, 1942–44

- Jürgen Stroop, HSSPF August–October 1943

- Walter Schimana, HSSPF October 1943-October 1944

- General Alexander Löhr, Commander, Army Group E, C-in-C South-East

- General Hubert Lanz, Commander, XXII Mountain Army Corps

- General Hellmuth Felmy, Military Commander, Southern Greece

- General Walter Stettner, Commander, 1st Mountain Division

- General Karl von Le Suire, Commander, 117th Jäger Division

- General Hartwig von Ludwiger, Commander, 104th Jäger Division

- General Friedrich-Wilhelm Müller, Commander, "Fortress Crete"

- General Heinrich Kreipe, Commander, 22nd Air Landing Infantry Division

- Dr. Max Merten, Chief of Military Administration, Salonika

- Dieter Wisliceny, responsible for the deportation of Salonika's Jews

- Friedrich Schubert, Wehrmacht paramilitary Sonderführer in Crete and Macedonia

Italian officials:

- Ambassador Pellegrino Ghigi, Italian Plenipotentiary 1941-43

- General Carlo Geloso, Commander, Italian 11th Army

and Supreme Commander of mainland Greece (Supergrecia) - Admiral Inigo Campioni, Governor of the Dodecanese

and Supreme Commander of the Aegean (Superegeo)

Leaders of secessionist movements:

- Andon Kalchev, pro-Bulgarian leader of the Ohrana

- Alchiviad Diamandi, self-proclaimed "Prince of Pindus"

- Nicola Matushi, close associate of Diamandi

British agents:

- Brigadier Eddie Myers, SOE

- Colonel Christopher Woodhouse, SOE

- Patrick Leigh Fermor, SOE

- Bill Stanley Moss, SOE

References

- ^ a b Mazower (2001), p. 155

- ^ Giannis Katris, The Birth of Neofascism in Greece, 1971

- ^ Andreas Papandreou, Democracy at Gunpoint (Η Δημοκρατία στο απόσπασμα)

- ^ K.Svolopoulos, Greek Foreign Policy 1945-1981

- ^ Famine and Death in Occupied Greece 1941-1944, Cambridge University Press

- ^ "Greece: Hungriest Country", Time, Feb. 09 1942

- ^ "Secret Not for Publication: Famine and Death Ride into Greece at the Heels of the Nazi Conquest", Life, Aug 3 1942, p. 28-29

- ^ Mark Mazower (1995). Inside Hitler's Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-44. Yale University Press, ISBN 0300089326.

- ^ Mazower (1995), pp. 44-48

- ^ Knopp (2009), p. 193

- ^ Chronik des Seekrieges 1939-1945, Württembergische Landesbibliothek, Section "War Crimes", entry on "23.9.— 19.10.1943"

- ^ Axis History Factbook

- ^ Reproduced articles from The Times and The Guardian

- ^ Fischer (1999), pp. 70-75

- ^ Fischer (1999), p. 85

- ^ Poulton, Hugh, Who are the Macedonians? Indiana University Press. (2000) p. 111

- ^ Mazower (2000), p. 46

- ^ K. Svolopoulos Greek Foreign Policy 1945-1981

- ^ a b Mazower (2000), p. 276

- ^ Demetres Tziovas, Greece and the Balkans: identities, perceptions and cultural encounters since the Enlightenment, page 37

- ^ Ion Dragoumis, Heroes' and Martyrs' Blood

- ^ RJ Crampton, Bulgaria, page 51 "gravely offended by textbooks which referred to Bulgarians as a barbaric tribe"

- ^ Miller (1975), p. 130

- ^ a b c Miller (1975), p. 127

- ^ Miller (1975), pp. 126-7

- ^ Mazower (1995), p. 20

- ^ Charles R. Shrader, The Withered Vine: Logistics and the Communist Insurgency in Greece, 1945-1949, 1999, Greenwood Publishing Group, p.19, ISBN 0275965449

- ^ Loring M. Danforth. The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-691-04357-9.p. 73.

- ^ The struggle for Greece, 1941-1949, Christopher Montague Woodhouse, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2002, ISBN 1850654921, p. 67.

- ^ Miller (1975), p. 128

- ^ Carl Savich, Balkanalysis article

- ^ Russell King, Nicola Mai, Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers, The New Albanian Migration, p.67, and 87

- ^ a b M. Mazower (ed.), After The War Was Over: Reconstructing the Family, Nation and State in Greece, 1943-1960, p. 25

- ^ Knopp (2009), p. 192

- ^ Twenty-Five Lectures on Modern Balkan History, by Steven W. Sowards

- ^ Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue and Museum, The Holocaust in Ioannina URL accessed January 5, 2009

- ^ Raptis, Alekos and Tzallas, Thumios, Deportation of Jews of Ioannina, Kehila Kedosha Janina Synagogue and Museum, July 28, 2005 URL accessed January 5, 2009

- ^ Mazower (2004), p. 424-28

- ^ Website of the Foundation for the Advancement of Sephardic Studies and Culture.

- ^ Mazower (2004), p. 443-48

- ^ History of the Jewish Communities of Greece, American Friends of the Jewish Museum of Greece

- ^ The Holocaust in Greece, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Sources

- Fischer, Bernd Jürgen (1999). Albania at War, 1939-1945. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 9781850655312. http://books.google.com/books?id=P-MiG9ngCp8C.

- Hatziiosif, Christos; Papastratis, Prokopis, eds (2007). Ιστορία της Ελλάδας του 20ού αιώνα, Γ' Τόμος: Β' Παγκόσμιος Πόλεμος. Κατοχή - Αντίσταση 1940–1945, Μέρος 1ο. [History of Greece in the 20th Century, Volume III: World War II. Occupation and Resistance 1940–1945, Part 1]. Athens: Bibliorama. ISBN 978-960-8087-05-7.

- Hatziiosif, Christos; Papastratis, Prokopis, eds (2007). Ιστορία της Ελλάδας του 20ού αιώνα, Γ' Τόμος: Β' Παγκόσμιος Πόλεμος. Κατοχή - Αντίσταση 1940–1945, Μέρος 2ο. [History of Greece in the 20th Century, Volume III: World War II. Occupation and Resistance 1940–1945, Part 2]. Athens: Bibliorama. ISBN 978-960-8087-06-4.

- Karras, Georgios (1985), The Revolution that Failed. The story of the Greek Communist Party in the period 1941–49 M.A. Thesis, Dept. of Political Studies. University of Manitoba, Canada.

- Knopp, Guido (2009) (in German). Die Wehrmacht - Eine Bilanz. Goldmann. ISBN 978-3-442-15561-3.

- Mazower, Mark (1995). Inside Hitler's Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941–44. Yale University Press. ISBN 0300089236.

- Mazower, Mark (2000). After the War was Over: Reconstructing the Family, Nation, and State in Greece, 1943-1960. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691058429. http://books.google.com/books?id=YAszKv6JfQUC.

- Mazower, Mark (2004). Salonica, City of Ghosts. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-712022-2.

- Miller, Marshall Lee (1975). Bulgaria during the Second World War. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804708708.

- German Antiguerrilla Operations in The Balkans (1941-1944). Washington DC: Center of Military History. 1953. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/ETO/East/Balkans/AG-Balkans.html.

- Helger, Bengt (1949) (in French). Ravitaillement de la Grèce, pendant l'occupation 1941-44 et pendant les premiers cinq mois après la liberation. Rapport final de la Commission de Gestion pour les Secours en Grèce sous les auspices du Comité International de la Croix-Rouge. Société Hellenique d'Editions.

External links

- Memorandum to the Note to the Greek Government, April 6, 1941

- Note of the Reich Government to the Greek Government, April 6, 1941

- Greece during World War II

Greece during World War II 1940–41 Balkans Campaign Occupation and Resistance Greek government in exile Battles: Elaia–Kalamas · Pindus · Morava–Ivan · Klisura · Trebeshina · Italian Spring Offensive

Commanders:

Greece

Greece

Ioannis Metaxas · Alexander Papagos · Charalambos Katsimitros

Italy

Italy

Sebastiano Visconti Prasca · Ubaldo Soddu · Ugo Cavallero · Giovanni MesseBattles: Metaxas Line · Vevi · Kleisoura Pass · Thermopylae · Crete

Commanders:

Greece

Greece

Alexander Papagos · Georgios Tsolakoglou

British Expeditionary Corps

British Expeditionary Corps

Henry Maitland Wilson · Thomas Blamey · Bernard Freyberg

Germany

Germany

Wilhelm List · Kurt StudentOccupying powersOccupation Authorities:

Germany

Germany

Günther Altenburg · Hermann Neubacher · Walter Schimana · Alexander Löhr · Hellmuth Felmy

Italy

Italy

Pellegrino Ghigi · Carlo Geloso

Bulgaria

BulgariaAtrocities: Kondomari · Kandanos · Doxato · Kommeno · Kalavryta · Distomo · Domenikon · Drakeia · Cephalonia · Paramythia · Mesovouno · Pyrgoi · Viannos · Kedros · Chortiatis · The Holocaust in Greece · Great Famine

CollaboratorsPeople: Georgios Tsolakoglou · K. Logothetopoulos · Ioannis Rallis · Georgios Poulos

Organizations: Collaborationist government · Security Battalions · ESPO · EEE · Greek National Socialist Party

Secessionists: Principality of the Pindus · Ohrana · Cham collaboration (Këshilla)

People: Aris Velouchiotis · Stefanos Sarafis · Georgios Siantos · Markos Vafiades · Evripidis Bakirtzis · Andreas Tzimas

Organizations: KKE · ELAS · PEEA · EPON · E.A. · OPLA · SNOF

Operations: Ryka · Mikro Chorio · Gorgopotamos Bridge · Fardykambos · Sarantaporo · Kournovo Tunnel

Non-EAM ResistancePeople: Napoleon Zervas · Georgios Kartalis · Dimitrios Psarros · Komninos Pyromaglou · Alexander Papagos · Kostas Perrikos · George Psychoundakis

Organizations: EDES · EKKA · YVE/PAO · PEAN · ΕΟΚ · E.S. · MAVI · Other

Operations: ESPO bombing · Gorgopotamos Bridge · Fardykambos · Agia Kyriaki · Milia · Skala Paramythias · Xirovouni · Menina · Dodona

Atrocities: Expulsion of Cham Albanians

British Mission in Greece (SOE)People: Eddie Myers · Chris Woodhouse · Patrick Leigh Fermor · Bill Stanley Moss

Operations: Operation "Albumen" · Gorgopotamos Bridge · Operation "Animals" · Asopos Bridge · Kidnap of General Kreipe · Damasta sabotage

Events: El Alamein · Dodecanese · April 1944 mutiny · Rimini

People: King George II · Emmanouil Tsouderos · Panagiotis Kanellopoulos

Notable units: 3rd Mountain Brigade · Sacred Band · Vasilissa Olga · Adrias · Katsonis · Papanikolis · 13th Squadron · 335th Squadron · 336th Squadron

Towards the Civil WarEvents: Plaka agreement · Lebanon conference · Caserta agreement · Percentages agreement · Dekemvriana · Treaty of Varkiza

People: Ronald Scobie · George Papandreou · Archbishop Damaskinos

Countries occupied by Nazi Germany during World War II Albania • Austria (Anschluss) • Belarus • Belgium • Channel Islands • Czechoslovakia • Denmark • Estonia • France • Greece • Hungary • Italy • Latvia • Lithuania • Luxembourg • Monaco • The Netherlands • Norway • Poland • San Marino • Ukraine • Yugoslavia

Categories:- 1940s in Greece

- Greece in World War II

- Jewish Greek history

- World War II Balkans Campaign

- World War II Mediterranean Theatre

- Military of Nazi Germany

- World War II occupied territories

- German occupations

- Antisemitism in Greece

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.