- Occupation of Belarus by Nazi Germany

-

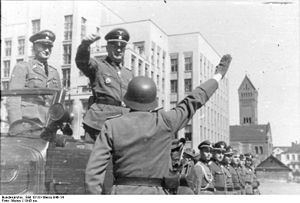

Occupation of Belarus by Nazi Germany Part of World War II

Mogilev Jews kidnapped for forced labour, July 1941Location The occupation of Belarus by Nazi Germany occurred as part of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941 (Operation Barbarossa) and ended in August 1944 with the Soviet Operation Bagration.

Background

The Soviet and Belarussian historiographies study this subject in context of Belarus, regarded as the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR, a constituent republic of the Soviet Union or USSR) in the 1941 borders as a whole. Polish historiography, or possibly part of it, insists on special, even separate treatment for the East Lands of the Poland in the 1921 borders (alias "Kresy Wschodnie" alias West Belarus), which were incorporated into the BSSR after the Soviet Union invaded Poland on September 17, 1939. More than 100,000 people in West Belarus were imprisoned, executed or transported to the eastern USSR by Soviet authorities before the German invasion. The NKVD (Soviet secret police) probably killed more than 1,000 prisoners in June/July 1941, for example, in Chervyen, Hlybokaye, Hrodna and Vileyka. These crimes stoked anti-Communist feelings in the Belarusian population and were used by Nazi anti-Semitic propaganda.

Invasion

Main article: Military history of Belarus during World War IIAfter twenty months of Soviet rule in Western Belarus and Western Ukraine, Nazi Germany and its Axis allies invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. Eastern Belarus suffered particularly heavily during the fighting and German occupation. Following bloody encirclement battles, all of the present-day Belarus territory was occupied by the Germans by the end of August 1941. Poland regarding the Soviet annexation as illegal, the majority of Polish citizens didn't ask for Soviet citizenship 1939-1941, so they were Polish citizens under Soviet and later Nazi occupation.

Occupation

Main article: Belarusian resistance during World War IISince the early days of the occupation, a powerful and increasingly well-coordinated Soviet partisan movement emerged. Hiding in the woods and swamps, the partisans inflicted heavy damage to German supply lines and communications, disrupting railway tracks, bridges, telegraph wires, attacking supply depots, fuel dumps and transports, and ambushing Axis soldiers. Not all of the anti-German partisans were pro-Soviet. In the largest[citation needed] partisan sabotage action of the entire Second World War, the so-called Asipovichy diversion of July 30, 1943, four German trains with supplies and Tiger tanks were destroyed. To fight partisan activity, the Germans had to withdraw considerable forces behind their front line. On June 22, 1944, the huge Soviet offensive Operation Bagration was launched, finally regaining all of Belarus by the end of August.

Military crimes

Main article: Anti-partisan operations in BelarusGermany imposed a brutal regime, deporting some 380,000 people for slave labour, and killing hundreds of thousands of civilians more. At least 5,295 Belarusian settlements were destroyed by the Nazis and some or all their inhabitants killed (out of 9200 settlements that were burned or otherwise destroyed in Belarus during World War II).[1] More than 600 villages like Khatyn were annihilated with their entire population.[1] Altogether, 2,230,000 people were killed in Belarus during the three years of German occupation.[1]

Soviet partisan fighters behind Nazi German front lines in Belarus in 1943

Soviet partisan fighters behind Nazi German front lines in Belarus in 1943

.

Anti-partisan operations

Anti-partisan operations in Belarus were also the anti-partisan, but in reality much more anti-civilian (against ethnic Belarusian peasants) military operations, on the territory of Belarus.

Major actions (spring 1942 to spring 1943)

Introduction and functioning of the New Tactic

In the first months of 1942 it turned out that the Belarusian partisans had not only made it through the winter, contrary to some predictions, but increased their activities despite reduced ranks and focused on new targets.

Belarusian Central Rada, Minsk, June 1943.

Belarusian Central Rada, Minsk, June 1943.

First locally and starting from the east of the country, then ever more powerfully towards the summer they tried to paralyze the Belarusian Central Rada as the key instrument of Nazi German exploitation of the country and German administrative action. Due to the German defeat before Moscow and the Soviet counterattack, which had brought the Red Army to the north eastern border of Belarus, the strategic and political position of Belarusian resistance during World War II had considerably improved. The Germans reacted to this development with a new tactic. It was worked out mainly by the regional military leadership in the rear area of Army Group Center, which in this respect also counseled the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) and worked in coordination with it. SS and police had little part in this, from what becomes apparent from the sources.

This was partially due to a weakness in leadership, because the Higher SS and Police Leader for Central Russia[disambiguation needed

], Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski - later a leading strategist of the fight against the partisans - was absent due to disease.

], Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski - later a leading strategist of the fight against the partisans - was absent due to disease.Between the end of January and the beginning of May 1942. No significant impulses from Einsatzgruppe B can be verified either. That General Max von Schenckendorff accorded the SS and police only a certain area to be secured indicates their secondary role.

The Army Supreme Command had in the second half of February required the commander of the rear area of Army Group Center to present a program for the annihilation of the partisans, apparently amongst others as a reaction to a memorandum by the Supreme Commander of Army Group Center, Günther von Kluge. The short-term goal was the Annihilation of the Partisans until the beginning of the mud period in April, at least in the area of the railways, main roads and in the Briańsk area. Von Schenkendorff called for measures in two directions: propaganda to influence the Russian population, and military annihilation of the partisans. Beside the political measures he declared it necessary to bring in troops - pointing out that units making up three divisions and two SS brigades had been taken away from him in the previous three months. He demanded a restructuring of the leadership organs and troops for an offensive conduction of operations and the allocation of means for offensive fighting (heavy weapons, airplanes, vehicles). He also called for building up the local order police, the creation of fighting unit made up of collaborators, the continuation of training courses and exchanges of experience, and intensification of the communications network and the fight against those alien to a locality. Von Schenkendorff submitted his suggestions orally to Franz Halder, Josef Wagner and Günther von Kluge. The problem was also forwarded to Adolf Hitler due to the efforts of the Albert Speer’s Department of War Economy and Armament at the Wehrmacht Supreme Command (OKW), the General Quarter Master and the leader of his section for war administration, Schmidt v. Altenstadt, who in connection with this matter repeatedly visited the rear area of Army Group Center in the spring of 1942.

The tactical mechanism of the major operations

Main article: Operation BambergWhat follows is an overview of the greatest of these operations, their temporal and regional distribution and the number of their victims:

Anti-partisan operations

(Codename; Period; Area; Number of dead civilians/partisans; Number of captured firearms; Number of dead in German formations.)

1942

- Operation Bamberg; March 26 - April 6; Hłusk, Bobrujsk; 4,396; 47; 7

- ?; May 9 - May 12; Kliczów, Bobrujsk; 520; 3; 10

- ?; Beginning of June; Słowodka, Bobrujsk; 1,000; ?; ?

- ?; 15.06; Borki, Białystok County; 1,741; 7; 0

- ?; 21.06; Zbyszin; 1,076; ?; ?

- ?; 25.06; Timkowczi; 900; ?;?

- ?; 26.06; Studenka; 836; ?;?

- ?; 18.07; Jelsk; 1,000; ?; ?

- Operation Adler; 15.07-07.08; Bobrujsk, Mohylew, Berezyna; 1,381; 438; 25

- Operation Greif; 14.08-20.08; Orsza, Witebsk; 796; ?; 26

- Operation Sumpffieber; 22.08-21.09; White Ruthenia; 10,063; ?; ?

- ?; 22.09-26.09; Małoryta; 4,038; 0; 0

- Operation Blitz; 23.09-03.10; Połock, Witebsk; 567; ?; 8

- Operation Karlsbad; 11.10-23.10; Orsza, Witebsk; 1,051; 178; 24

- Operation Nürnberg; 23.11-29.11; Dubrowka; 2,974; ?; 6

- Operation Altona; 22.12-29.12; Słonim; 1,032; ?; 0

1943

- Operation Franz; 06.01-14.01; Grodsjanka; 2,025; 280; 19

- Operation Peter; 10.01-11.01; Kliczów, Kolbcza; 1,400; ?; ?

- ?; 18.01-23.01; Słuck, Mińsk, Czerwień; 825; 141; 0

- Operation Waldwinter; until 01.02; Sirotino-Trudy; 1,627; 159; 20

- Operation Erntefest I; until 28.01; Czerwień, Osipowicze; 1,228; 163; 7

- Operation Erntefest II; until 09.02; Słuck, Kopyl; 2,325; 314; 6

- Operation Hornung; 08.02-26.02; Lenin, Hancewicze; 12,897; 133; 29

- Operation Schneehase; 28.01-15.02; Połock, Rossony, Krasnopole; 2,283; 54; 37

- Operation Winterzauber; 15.02 - end of March; Oświeja, Latvian border; 3,904; ?; 30

- Operation Kugelblitz; 22.02-08.03; Połock, Oświeja, Dryssa, Rossony; 3,780; 583; 117

- Operation Nixe; until 19.03; Ptycz-Mikaszewicze, Pińsk; 400; ?; ?

- Operation Föhn; until 21.03; Pińsk; 543; ?; 12

- Operation Donnerkeil; 21.03-02.04; Połock, Witebsk; 542; 91; 5

- Operation Draufgnger II; 01.05-09.05; Rudnja and Manyly forest; 680; 110; 0

- Operation Cottbus; 20.05-23.06; Lepel, Begomel, Uszacz; 11,796; 1,057; 128

- Operation Ziethen; 13.06-16.06; Rzeczyca; 160; ?; 5

- ?; 30.07; Mozyrz; 501; ?; ?

- Operation Günther; until 14.07; Woloszyn, Lagoisk; 3,993; ?; 11

- Operation Fritz; 24.09-10.10; Głębokie; 509; 46; 12

- ?; 09.10 - 22.10; Stary Bychów; 1,769; 302; 64

- Operation Heinrich; 01.11-18.11; Rossony, Połock, Idrica; 5,452; 476; 358

- ?; December; Spasskoje; 628; ?;?

- ?; December; Biały[disambiguation needed

]; 1,453; ?; ?

]; 1,453; ?; ?

- Operation Otto; 20.12-01.01.1944; Oświeja; 1,920; 30; 21

1944

- ?; 14.01; Oła; 1,758; ?; ?

- ?; 22.01; Baiki; 987; ?; ?

- Operation Wolfsjagd; 03.02-15.02; Hłusk, Bobrujsk; 467; ?; 6

- Operation Sumpfhahn; until 19.02; Hłusk, Bobrujsk; 538; ?; 6

- ?; Beginning of March; Berezyna, Bielnicz; 686; ?; ?

- Operation Auerhahn; 07.04-17.04; Bobrujsk; 1,000; ?; ?

- Operation Frühlingsfest; 17.04-12.05; Połock, Uszacz; 7,011; 1,065; 300

- Operation Pfingstausflug; June; Sienno; 653; ?; ?

- Operation Windwirbel; June; Chidra; 560; 103; 3

- Operation Pfingsrose; 02.06-13.06; Talka; 499; ?; ?

Biełaruskaja Krajowaja Abarona, Minsk, June 1944.

Biełaruskaja Krajowaja Abarona, Minsk, June 1944.

This overview is based on a multitude of sometimes incomplete, contradictory or unclear data. It can especially be proven only for given individual cases that reported prisoners were shot, although this should have been the rule. The density of sources is very different for the various operations. Nevertheless a number of tendencies and connections become apparent. The operations were carried out to an equal degree by SS and police and by the Wehrmacht. As far as can be established, 23 of the cases here presented were operations by SS and police and 15 were Wehrmacht operations. In eight other operations both participated with about equally strong forces. There was a far-reaching co-operation. The Wehrmacht operations were not substantially less damaging and brutal than those of the SS.

The overview especially shows very clearly who were the victims of German major operations between 1942 and 1944. The relation between the number of so-called enemy dead or those liquidated or shot self-explanatory terms on the one hand and the number of captured rifles, machine pistols and machine guns on the other was usually between 6:1 and 10:1. As since the end of 1942 at the latest every partisan possessed such a weapon. New members had to bring one along, meaning that about 10 to 15 percent of the victims of the German actions were partisans. The remaining 85 to 90 percent were mainly peasants from the surroundings and refugees. This is confirmed by the extremely low German losses, the relation of German dead to those on the other side usually being 1:30 to 1:300, on average 1:100.

What these relations meant was generally known among the German occupation officials in Belarus. For instance, General Commissar Wilhelm Kube wrote about a preliminary report received from SS and Police Leader Curt von Gottberg about the operation Cottbus, according to which there had been 4,500 enemy dead and 5,000 dead bandit suspects. Kube commented as follows:

- "If only 492 rifles are taken from 4,500 enemy dead, this discrepancy shows that among these enemy dead were numerous peasants from the country. The Battalion Dirlewanger especially has a reputation for destroying many human lives. Among the 5,000 people suspected of belonging to bands, there were numerous women and children."

Reich Commissar Hinrich Lohse forwarded Kube’s report with the following note:

- "What is Chatyń compared to this? To lock men, women and children into barns and to set fire to these, does not appear to be a suitable method of combating bands, even if it is desired to exterminate the population."

Later on Kube again criticized the major actions, during which, mainly as bandit suspects, men, women and children are shot. The former commander of the Minsk Ordnungspolizei Eberhard Herf, now chief of staff at the Commander of Anti-Bandit Units of the Reichsführer SS, also received Kube’s report that:

- "Some 480 rifles were found on 6,000 dead partisans. Put bluntly, all these men had been shot to swell the figure of enemy losses and highlight our own heroic deeds."

Answer:

- "You appear not to know that these bandits destroy their weapons in order to play the innocent and so avoid death. How easy it must be then to suppress these guerrillas - when they destroy their weapons!"

That the troops and commanders of anti-partisan actions were often cowardly and tried to embellish their success was one of the reasons for such balances. However, it was not the main reason for destroying part of the rural population; this was inherent to the conception and objectives of the operations. Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski claimed at his trial in Munich in 1949 that the partisans had always hidden or buried their weapons before capture if not immediately killed by a shot in the head. He was not the only one to make this claim. The commander of the rear area of Army Group Center issued an order that the rifles of the partisans should be collected more carefully as their number was out of proportion to the number of bandits killed or captured. The anti-partisan warfare expert of the commander of Sicherheitspolizei and SD Minsk, Artur Wilke, documented in his personal notes of 1943 this practice which made it possible to very much spare his own troops. He described the attack on a village the inhabitants of which fled and were fired at:

- "There were a number of dead which the battalion reported as enemy dead. There is hardly any evidence, however, that they were really partisans. I tell the major that we had previously counted such dead as partisan suspects, but he counts them as liquidated. His terminology is unclear to me but seems to have the purpose of increasing the number of bandits killed in battle."

Although the German attacks were directed primarily against the peasant civilian population, operations wholly without fighting against partisans were rather the exception. The fight against partisans took place mainly on the fringes of the partisans’ operational area. Fighting rarely took place in areas where there were no partisans at all, which is not to say that the inhabitants of the destroyed villages had actively supported the partisans.) Their bases proper were attacked only during a part of the operations. The better German armament (Luftwaffe, artillery) led to their losses being considerably higher than those of the Germans and their allies and auxiliaries, as the discrepancy between captured weapons and German losses shows. In the time after the partial retreat in the autumn of 1943 the fighting became tougher and German losses rose, because the density of German troops was greater and the task of armed resistance was now a military one in a more narrow sense. From the point of view of the partisans the expected relief did not occur. The losses of the partisans proper were rather low because they usually avoided frontal engagements.

The Germans rarely attacked the partisans directly, even though encirclement was possible, and instead fought the peasants in the surroundings. The inaccessible terrain, better knowledge of the area by the partisans, cowardice and over-aging of the German troops were some of the reasons. The partisans also usually managed to escape the German encirclement by withdrawing, slipping or breaking through. The main reason, however, was the following: as in the case of other guerrilla movements the military attacks of the partisans and their own losses were not the most dangerous aspect from the point of view of the German occupation authorities. What concerned them more was the partisans’ growing political influence upon the local population. The partisans were thus to be isolated from the peasants at any cost. The more the armed resistance drew the peasants to its side, the less agrarian products they delivered to the Germans. The main interest of the occupiers, however, was to have a population as loyal and willing to deliver as possible. Where the population sided with the partisans, it became a threat to German rule through its disobedience, and as it was easier to hit, the occupiers concentrated on wiping out the villages influenced by the partisans in order to keep the political infection from spreading.

Concretely this connection was seen by the German side as follows: partisan camps were usually located in greater forest areas. From there they tried to paralyze the administrative and agricultural system in the surroundings. From the beginning of 1942 the peasants were gradually convinced or coerced into refraining from deliveries of agricultural products to the Germans. The local starosts, mayors, policemen and administrative employees were intimidated or attacked. When the Germans were no longer receiving agricultural products from these areas, they no longer had to take into consideration whether the agricultural production in these areas would be damaged [by these actions] or cease altogether. Hermann Göring stated in October 1942:

- "Germany lost nothing through the death of these peasants. This applied at least to such areas which expectably cannot be pacified even after having been combed through."

The devastation benefited the occupying power by preventing spill-over of resistance to other agriculturally important regions. The inhabitants of in the partisans’ areas of influence were in part correctly suspected of voluntarily or involuntarily supplying food, other necessities and information to the resistance movement. In murdering or resettling these people, the Germans did not seek to establish the guilt of those supporting the partisans, but to deprive the partisans of support, lodging and food.[2] A former participant testified as follows:

- "We members of EK VIII reacted thereto by destroying whole villages in this area, the inhabitants of which we shot. Our goal was to deprive the partisans in the wood of any means to avail themselves of food, clothing etc. from these localities. In one or two cases we members of EK VIII combed through wood in this area to track down the partisans in their hideouts. Such methods we quickly gave up, however. We considered them too dangerous for us, as we might ourselves be attacked and destroyed by the partisans."

Almost all anti-partisan actions were directed against the areas bordering on huge forests or villages in the forest. Individual witnesses and perpetrators later recalled this tactic. For instance, the former commander of SS police regiment 26,[3][4] Georg Weisig, stated the following about operation Otto around the end of 1943/beginning of 1944:

- "About two hundred and fifty inhabitants of the villages located outside the woods we transported to camps. The people found in villages inside the forest area, however, were all killed.[citation needed] In the whole area between Siebież and Lake Osweskoje where the operation had been carried out there was not a single living human being left after our regiment had passed through."[citation needed]

Sources show that during major operations the German units and their auxiliaries marched exclusively on the streets and overhauled villages, as already shown in regard to Operation Bamberg. It was not to be expected that partisans would be encountered. SS-Hauptsturmführer Wilke of the security police and SD command Minsk wrote about the commander of a police battalion to which he had been detached:

- "I have the impression that the commander wants to very much spare his troops or doesn't consider them up to much."

He tended to approach the areas of operation as much as possible with motorized vehicles. His superior, commander of security police and SD Eduard Strauch (de:Eduard Strauch), in April 1943 openly commented before a huge public that the German formations were very cumbersome [schwerfüllig] as troops, so that due to bad communications the partisan bases were not reached. In the report about Operation Waldwinter of the 286th Security Division the following was stated:

- "As targets of attack almost exclusively roads with adjacent villages were chosen in order to make possible good communications right and left despite the difficult road conditions."[2]

Wiping out the villages

The destruction of village seemed to the inhabitants to be casual, without a reason, unexplainable, or they believed there had been a confusion. Coincidences, arbitrariness and blind violence may have played a part, but the German decisions about death or life generally followed strategic lines, which remained hidden from the victims. There were a number of factors that determined the fate of a village and its inhabitants when it came within the scope of a German major action. In most cases a village was first occupied in a surprise attack, preferably at dawn either after having been encircled or by armed men swarming out from its center. In almost every case the village’s whole population was then assembled, there often being a control of identity papers. Those who fled or hid themselves were shot down according to general instructions. In many cases, the destruction of a village had been decided upon beforehand. If not, there followed interrogations and examinations. The Germans shot strangers and those families whose male members were absent without a reason the Germans considered sufficient. A family was also considered suspect of banditry and thus doomed to die if, for instance, there were more coats than people in its house. Often the German units came with prepared death lists based on denunciations of the collaborator administration. The respective houses in the locality were marked with writings such as “partisan” or “bandit house”.

Discoveries of weapons or ammunition were in most cases considered as sufficient reason to murder the inhabitants of a whole village. Alleged or actual explosions of ammunition in the houses during the burning of the village were provided as evidence that had not existed at the beginning of the destruction. In some cases the population would not have had the alleged materials, such as German equipment or German gasoline. Villages in the regions that had been Polish until 1939 where collectivization of agriculture had already been carried out were deemed suspicious from the start. But as a rule the German decision to annihilate was based on the results of German reconnaissance by the security police and the SD or the Geheime Feldpolizei. These in turn relied on often casual denunciations of whole villages by local collaborators or German organs on site: Landwirtschaftsführer (heads of agricultural administration), forest or road administration, or local commanders. Where there were warnings, the population often managed to flee the villages before the German assault, so that the Germans found them empty. In one case in the vicinity of Słonim the old remained behind in their death shirt, washed clean and fully prepared for their death at the hands of the Germans.

The course of the massacres in the doomed places shows an organized procedure by the German units and their helpers. In more than a few cases there were shootings at pits similar to the executions of Jews by SS, police and Wehrmacht, carried out with machine guns. In other cases the killing took place in barns, stables or larger buildings, sometimes by burning the people alive. These places of execution were meant to keep the victims from running apart and escaping. The third possibility was that every single family was arrested in its house and there killed by gunfire especially from machine pistols and hand grenades. After this the houses were burned down. Special detachments were in charge of the burning of the villages. Sometimes all inhabitants of every single house were registered days before, in a few cases gas vans were used as murder tools.

Buildings were set on fire not only meant to deprive partisans later passing through the village of shelter, but also to ensure that any survivors of the massacres died in the fires. The buildings set on fire were often kept surrounded. The killing methods employed, machine guns and hand grenades, often left some people alive.

There were differences of opinion on the German side about the tactical value of burning down partisan villages. It was supported, for example, by the commander of the rear area of Army Group Center, v. Schenckendorff, and the commander of the security police and SD Minsk Strauch. Others, such as the Regional Commissariat Żytomierz, and head of SS and police Otto Hellwig, may have favored burning down in principle, but saw the need to reserve buildings as quarters for German units stationed in Belarus.

Before the destruction of villages, their inhabitants had not been murdered if they were needed as a labor force, for instance on streets and railway lines. Thus in Glusza along the important street Słuck-Bobrujsk (Durchgangsstrasse VII) the inhabitants had been locked into a barn to be murdered but were liberated upon intervention by a local German occupation official. At the beginning of 1943 the Luftwaffe Command East recommended that the burning of villages as retaliation for a nearby attack on the railways ordered by Göring not to be carried out where a pacification still seemed possible. In the regions dominated or heavily infected by the partisan bands, the harshest measures were to be taken. Air force units showed themselves to be especially brutal in the fight against the partisans.[5]

The climax of the war against the peasants: Operations Hornung and Cottbus

Main articles: Operation Hornung and Operation CottbusDuring 1942 the Germans had developed a new tactic of the major operations and mase it the standard measure of pacification in wide areas of Belarus. In 1943 the climax of the war against the rural population took place. In the White Ruthenia Regional Commissariat, Kampfgruppe Curt von Gottberg led the attack on the villages. In the area under military administration the 201st and 286th security divisions, and the forces of the 3rd Panzer Army and SS and Police Leader Ostland Friedrich Jeckeln ravaged the north of the country with his units. In the Żytomierz Regional Commissariat, the SS and Police Leader Ukraine was active with forces transferred there specifically for this purpose.

According to the statistic prepared by the working group around Romanowski the Germans committed massacres in 5,295 localities in Belarus; 3 percent of these cases occurred in 1941, 16 percent in 1942, no less than 63 percent in 1943 and 18 percent in 1944. The number of victims increased almost fourfold from 1942 to 1943.[6]

Number of victims

It is not possible to establish the total number of people killed by the Germans and their auxiliaries during the fight against partisans in Belarus. Only approximations can be made. There are several ways to determine a total number of victims. Posterior research on reports about individual cases, such as published by the working group around Romanowski[clarification needed], cannot be accurate due to the vast number of affected villages, and the lack of surviving witnesses able to provide exact data and the enormous research effort. They only provide minimum numbers because only positively verifiable cases are therein taken into consideration. In the more than 5,000 villages covered by Romanowski more than 147,000 inhabitants died. 627 villages were completely destroyed, and 186 thereof remained wastelands after the war. For comparison: In Lithuania there were 21 scorched villages, and in the Ukraine, 250.

The Germans also had problems with their murder statistics, due in part to the camouflage language used in the reports. There are differences and discrepancies between the monthly reports and the addition of the daily reports of units involved. The murder detachment, however, did not report false numbers, as shown for instance by posterior examinations in the two villages called Borki[disambiguation needed

] (Kirov[disambiguation needed

] (Kirov[disambiguation needed  ] Raion {Kirov, Kaluga Oblast?} and Małoryta raion). The individual German data can be considered reliable.[citation needed] It is especially unclear to what extent the data in the monthly reports of Wehrmacht, SS and police include the victims of the major actions. A number of reports can be proven to have included only the smaller actions. This practice was insufficiently taken into consideration by Timothy Mulligan in his calculation attempts.[citation needed] As he further argued on the basis of incomplete sources, especially in regard to the Regional Commissariat White Ruthenia, the number he established at least 243,800, probably more than 300,000 deaths in the area of Army Group Center together with the Regional Commissariat White Ruthenia is probably too low. In this respect considerable territorial differences in relation to the territory of Belarus must be taken into consideration.

] Raion {Kirov, Kaluga Oblast?} and Małoryta raion). The individual German data can be considered reliable.[citation needed] It is especially unclear to what extent the data in the monthly reports of Wehrmacht, SS and police include the victims of the major actions. A number of reports can be proven to have included only the smaller actions. This practice was insufficiently taken into consideration by Timothy Mulligan in his calculation attempts.[citation needed] As he further argued on the basis of incomplete sources, especially in regard to the Regional Commissariat White Ruthenia, the number he established at least 243,800, probably more than 300,000 deaths in the area of Army Group Center together with the Regional Commissariat White Ruthenia is probably too low. In this respect considerable territorial differences in relation to the territory of Belarus must be taken into consideration.The rear area of Army Group Center (eastern Belarus) reported 100,000 liquidated partisans from the beginning of 1942 until January 1943. Adding in the reports of the Army Group after the dissolution of the rear area in the autumn of 1943, this number grew to 164,800 by June 1944, not including the major operations. These numbers also include prisoners, which raises two issues: (1) only some prisoners were later murdered, and (2) there was an instruction to report prisoners in certain cases when actually the people had been executed. The official numbers are thus hard to evaluate, but they are probably understated.[citation needed]

In the White Ruthenia Regional Commissariat v. Gottberg reported 33,378 killed for November 1942 to March 1943 alone, including 11,000 Jews. There should also be included an uncertain portion of those 19,000 people shot by the 707th infantry division between September 1941 and January 1942. Extrapolations lead to a total of 345,000 people murdered during German anti-partisan operations in Belarus, i.e.,

- 160,000 in the rear area of Army Group Center,

- 120,000 in the White Ruthenia Regional Commissariat and

- 20,000 in each of the Żytomierz Regional Commissariat, the Wołyń-Podole Regional Commissariat and the area of the 3rd Panzer Army,

- 5,000 in the Bezirk Bialystok.

(In each case, the numbers indicate the parts of these regions presently belonging to Belarus).

For the rear area of Army Group Center, from autumn 1943, there were 200,000 victims including the major operations; 20 percent were deducted for the Russian areas.

For the White Ruthenia Regional Commissariat it was assumed that there were roughly 1,500 victims per month from September 1941 to October 1942 and 5,000 per month since November 1942. (For the other territories see previous sections).

In the 55 major actions listed in table alone the Germans killed at least 150,000 people, including 14,000 Jews. Additionally 17,000 prisoners and wounded were mentioned, most of whom are likely to have been murdered. 12,000 people were resettled or evacuated, about 100,000 deported as forced laborers. These figures, however, do not include the victims of the smaller and middle-size actions, which in the Belarusian part of the Army Group Center rear area alone had already claimed about 40,000 victims until the beginning of 1942.

Police Regiment 2, for instance, killed 733 people within a month in 1943 during the three middle-size operations Manyly, Lenz and Lenz Süd, and 1,298 during smaller operations and ongoing security and pacification tasks.

In the White Ruthenia General Commissariat police and Wehrmacht shot 3,366 alleged partisans between July and September 1942, not including shootings that were part of Operation Sumpffieber. The same applies for the Wołyń-Podole Regional Commissariat and the rear area of Army Group Center.

This indicates that the order of magnitude of the above estimate is accurate. The same applies if the number of slain partisans is taken into consideration. According to Pjotr Kalinin the partisan groups lost 26,000 dead and 11,800 missing; most of the latter must be considered to have lost their lives, as the membership registration of the partisan units may be considered reliable).[7] If the total number of dead was about 345,000, these numbers coincide with the relation established above: hardly more than one tenth of the victims of German major anti-partisan actions was actually a partisan. To these must be added, however, many mostly unarmed people in the so-called family labor camps.

The number killed by German perpetrator units is unknown. The most murderous included the 36th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Dirlewanger, the SS police regiments 2, 13, 22 and 23, the Schutzmannschaft Wacht Bataillon nr. 57 and the Gendarmerie-Einsatzkommando z.b.V. Kreikenbom. Police Battalion 307 [8][9] (later 1st Battalion Police Regiment 23) killed more than 4,000 people between December 1942 and March 1943 alone during seven major operations. Police Regiment 22 took part in at least 21 such actions within a period of 18 months.

The most infamous unit, however, was the Dirlewanger Battalion. It took part in 14 major operations between March 1942 and July 1943 and wiped out an especially large number of huge villages with all their inhabitants, including Borki[disambiguation needed

] (rayon Kirov), Zbyszin, Krasnica, Studenka, Kopacewiczi, Pusiczi, Makowje, Bricalowiczi, Welikaja Garosza, Gorodec, Dory, Ikany, Zaglinoje, Welikije Prussy and Perechody.

] (rayon Kirov), Zbyszin, Krasnica, Studenka, Kopacewiczi, Pusiczi, Makowje, Bricalowiczi, Welikaja Garosza, Gorodec, Dory, Ikany, Zaglinoje, Welikije Prussy and Perechody.According to Soviet sources, a total of 150 villages and 120,000 people fell victim to it in the Woblasts of Mińsk and Mohylew. Curt von Gottberg on the other wrote that Dirlewangers men had until mid-1943 annihilated about 15,000 partisans. Many different units participated in the murders including the security divisions, the groups of the Geheime Feldpolizei, and the detachments of the Sicherheitspolizei and the SD.[10]

Nazi units

Main article: Foreign relations of the Axis of World War II#Belarus- 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Galicia (1st Ukrainian)

- 29th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS RONA (1st Russian)

- 30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Belarussian)

- 30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (2nd Russian)

- 36th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS

- Arajs Kommando

- Einsatzgruppen

- Lithuanian Security Police

- Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force

- Nachtigall Battalion

- Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists

- Ypatingasis būrys

Notable Nazi personnel

- Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski

- Gustavs Celmiņš

- Oskar Dirlewanger

- Curt von Gottberg

- Konrāds Kalējs

- Bronislav Kaminski

- Wilhelm Kube

- Anthony Sawoniuk

Other units and participants

- 36th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS#Belarus

- Arturs Sproģis#Soviet partisan

- Army Group Centre#Early anti-partisan Campaign

- Battle of Murowana Oszmianka

- Belarusian partisans

- Belarusian resistance during World War II

- Collaboration during World War II#Belarus

- Consequences of German Nazism#Belarus

- Holocaust in Belarus

- Latvian partisans#Anti-Nazi

- List of Axis named operations in the European Theatre

- Lithuanian Territorial Defense Force

- Military history of Belarus during World War II#Belarusian Anti-Soviet commanders

- Pērkonkrusts

- Soviet partisans#Belarus

- Ukrainian-German collaboration during World War II

Holocaust

Main article: Holocaust in BelarusAlmost the whole, previously very numerous, Jewish population of Belarus which did not evacuate was killed. One of the first uprisings of a Jewish ghetto against the Nazis occurred in 1942 in Belarus, in the small town of Lakhva (see Lakhva Ghetto). The largest Jewish ghetto in Belarus was the Minsk Ghetto.

Post-occupation

Later in 1944, 30 German-trained Belarusians were airdropped behind the Soviet front line to spark disarray. These were known as "Čorny Kot" ("Black Cat") led by Michał Vituška. They had some initial success due to disorganization in the rear guard of Red Army. Other Belarusian units slipped through Białowieża Forest and full scale guerilla war erupted in 1945. But the NKVD infiltrated these units and neutralized them until 1957.

In total, Belarus lost a quarter of its pre-war population in the Second World War, including practically all its intellectual elite. About 9,200 villages and 1,200,000 houses were destroyed. The major towns of Minsk and Vitebsk lost over 80% of their buildings and city infrastructure. For the defence against the Germans, and the tenacity during the German occupation, the capital Minsk was awarded the title Hero City after the war. The fortress of Brest was awarded the title Hero-Fortress.

See also

- Battle of Brześć Litewski

- Battle of Smolensk (1941)

- Brest-Litovsk fortress

- Čorny Kot

- Consequences of German Nazism

- Eastern Front (World War II)

- Katyn massacre

- Khatyn massacre

- Łachwa Ghetto

- Maly Trostenets extermination camp

- Military history of Belarus during World War II

- Operation Tempest

- Narodowe Siły Zbrojne

- Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union

- Sluzk Affair

- Soviet partisan

- West Belarus

- 30th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Belarussian)

People

- Radasłaŭ Astroŭski

- Emmanuel Jasiuk

- Źmicier Kasmovič

- Mikałaj Łapicki

- Pyotr Masherov

- Jury Sabaleŭski

- Michał Vituška

Footnotes

- ^ a b c (English) "Genocide policy". Khatyn.by. SMC "Khatyn". 2005. http://www.khatyn.by/en/genocide/expeditions/. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ^ a b Christian Gerlach, Kalkulierte Morde. Die deutsche Wirtschafts- und Vernichtungspolitik in Weißrußland 1941 bis 1944. Studienausgabe, pages 898 and following

- ^ Police Regiments - Research

- ^ Die deutsche Polizei

- ^ Christian Gerlach, Kalkulierte Morde. Die deutsche Wirtschafts- und Vernichtungspolitik in Weißrußland 1941 bis 1944. Studienausgabe, pages 914 and following

- ^ Christian Gerlach, Kalkulierte Morde. Die deutsche Wirtschafts- und Vernichtungspolitik in Weißrußland 1941 bis 1944. Studienausgabe, pages 943 and following

- ^ Kalinin, Pjotr Sacharovich, Die Partisanenrepublik. Translated by N. P. Bakajeva, East Berlin, 1968, page 402

- ^ 2.6.4

- ^ Christopher Browning, Nazi Policy, Jewish Workers, German Killers

- ^ Christian Gerlach, Kalkulierte Morde. Die deutsche Wirtschafts- und Vernichtungspolitik in Weißrußland 1941 bis 1944. Studienausgabe, pages 955 and following

External links

- Biełaruskaja Krajovaja Abarona

- Communication from the Commissar for White Ruthenia, Kube, to Rosenberg, Concerning Appropriation of Cultural Objects by the SS and the Wehrmacht

- MILITARY TRIBUNAL II SITTING IN THE PALACE OF JUSTICE NUREMBERG, GERMANY

- Partisan Resistance in Belarus during World War II

- Khatyn - Genocide policy

- Years of nazi occupation (1941 - 1944)

- Беларусь у Другой сусветнай вайне (belarusian)

- Вітушка Міхал (belarusian)

- Вялікая Айчынная вайна на тэрыторыі Беларусі (belarusian)

- Сяргей Ёрш "Адважны генэрал" (belarusian)

- Interviews from the Underground:Eyewitness accounts of Belarus' Jewish resistance during World War II documentary film and website.

- How many Belarusians perished during the war?

- An Online Memorial of Those Rescued by the Bielski Partisans and Survived the Holocaust from Lida Lida Memorial Society Homepage Stories and Pictures

- Partisan Resistance in Belarus during World War II

- "Dirlewanger" units in Wołożyn

- Belarusian Nazi during the World War II and their work for the Cold War

- Borderlands

- The Prisoners of Silence - NSDAP 1936-1991

- Hitler's White Russians: Collaboration, Extermination and Anti-Partisan Warfare in Byelorussia, 1941-1944

- RUSSIAN FRONT (Books Dealing With the Russo-German War)

- German troops nip at Grodno. June 23, 1941.

- The Atrocities committed by German-Fascists in the USSR

Countries occupied by Nazi Germany during World War II Albania • Austria (Anschluss) • Belarus • Belgium • Channel Islands • Czechoslovakia • Denmark • Estonia • France • Greece • Hungary • Italy • Latvia • Lithuania • Luxembourg • Monaco • The Netherlands • Norway • Poland • San Marino • Ukraine • Yugoslavia

Categories:- History of Belarus (1939–1945)

- Military history of Belarus during World War II

- World War II occupied territories

- Politics of World War II

- Jewish Belarusian history

- 20th century in Belarus

- German occupations

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.