- Christopher C. Kraft Jr. Mission Control Center

-

For other places with the same name, see Mission control center.

The White Flight Control Room prior to STS-114 in 2005

The White Flight Control Room prior to STS-114 in 2005

NASA's Christopher C. Kraft, Jr. Mission Control Center (MCC-H), also known by its radio callsign, Houston, at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas, manages all American human space flight; including US portions of the International Space Station (ISS). The center is named after Christopher C. Kraft, Jr, a retired NASA engineer and manager who was instrumental in establishing the agency's Mission Control operation.[1]

The MCC currently houses two operational control rooms, from which flight controllers coordinate and monitor space shuttle missions and the ISS. These rooms have many computer and data-processing resources to monitor, command and communicate with spacecraft. From the moment a space shuttle clears its launch tower in Florida until it lands on Earth, it is in the hands of Mission Control. When a shuttle mission is underway, its control room is staffed around the clock, usually in three shifts. The ISS control room operates continuously, but with fewer controllers.

Because Houston is a hurricane-sensitive area, NASA has basic back-up facilities for shuttle missions at the Kennedy Space Center as well as a back-up location at MCC Moscow for ISS operations. (Unmanned US civilian satellites are controlled from the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, while California's Jet Propulsion Laboratory manages unmanned US space probes.)

Contents

Mercury Control at Cape Canaveral during Mercury-Atlas 8 in 1962

Mercury Control at Cape Canaveral during Mercury-Atlas 8 in 1962

All Mercury–Redstone, Mercury-Atlas, the unmanned Gemini 1 and Gemini 2, and manned Gemini 3 missions were controlled by the Mission Control Center (called the Mercury Control Center through 1963) at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Florida. This facility was in the Engineering Support Building at the east end of Mission Control Road, about 0.5 mile (0.8 km) east of Phillips Parkway. Launches were conducted from separate blockhouses at the Cape.

The building, which was on the National Register of Historic Places, was demolished in May 2010 due to concerns about asbestos and the estimated $5 million cost of repairs after 40 years of exposure to salt air. Formerly a stop on the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex tours; in the late 1990s, the control room consoles were removed, refurbished, and relocated to a re-creation of the room in the Debus Center at the KSC Visitor Complex.[2]

Houston (1965–present)

Apollo Mission Control Center MOCR 2 during Apollo 13 in 1970

MOCR 2 during Apollo 13 in 1970Location: Houston, Texas Coordinates: 29°33′29″N 95°5′18″W / 29.55806°N 95.08833°WCoordinates: 29°33′29″N 95°5′18″W / 29.55806°N 95.08833°W Built: 1965 Architect: Charles Luckman Architectural style: International Governing body: NASA NRHP Reference#: 85002815[3] Added to NRHP: October 3, 1985 Gemini and Apollo (1965-1975)

Located in Building 30 at the Johnson Space Center (known as the Manned Spacecraft Center until 1973), the Houston MCC was first used in June 1965 for Gemini 4. It housed two primary rooms known as Mission Operation Control Rooms (MOCR, pronounced "moh-ker").

MOCR 2 at the conclusion of Apollo 11 in 1969

MOCR 2 at the conclusion of Apollo 11 in 1969

These two rooms controlled all Gemini, Apollo, Skylab, and Space Shuttle flights up to 1998. Each consisted of a four-tier auditorium, dominated by a large map screen, which, with the exception of Apollo lunar flights, had a Mercator projection of the Earth, with locations of tracking stations, and a three-orbit "sine wave" track of the spacecraft in flight. Each MOCR tier was specialized, staffed by various controllers responsible for a specific spacecraft system.

MOCR 1, housed on the second floor of Building 30, was used for Apollo 7, the Skylab and the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project missions. MOCR 2 was used for all other Gemini and Apollo flights (except Gemini 3) and was located on the third floor. MOCR 2 was the flight control room for Apollo 11, the first manned moon landing. Because of this, MOCR 2 was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1985. It was last used in 1992 as the flight control room for STS-53 and was subsequently converted back almost entirely to its Apollo-era configuration and preserved for historical purposes. Together with several support wings, it is now listed in the National Register of Historic Places as the "Apollo Mission Control Center".[4]

Space Shuttle (1981–2011)

Flight Control Room 1 during STS-30 in 1989

Flight Control Room 1 during STS-30 in 1989

When the Space Shuttle program began, the MOCRs were re-designated flight control rooms (FCR, pronounced "ficker"); and FCR 1 (formerly MOCR 1) became the first shuttle control room. FCR 2 was used mostly for classified Department of Defense shuttle flights, then was remodeled to its Apollo-era configuration.

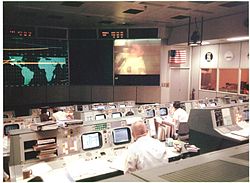

In 1992, JSC began building an extension to Building 30, sometimes called MCC 2. The new five-story section (30 South) went operational in 1998 and houses two flight control rooms, designated White and Blue. The White FCR was used in tandem with FCR 2 for seven shuttle missions, STS-70 through STS-76, and handled all following shuttle flights.

International Space Station (1998–present)

The newer section of Building 30 also houses the International Space Station Flight Control Room. The first ISS control room, originally named the Special Vehicles Operations Room (SVO), then the Blue FCR, was operational around the clock to support the ISS until the fall of 2006.

FCR 1, meanwhile, had its original consoles and tiered decking removed after STS-71, and was first converted to a "Life Sciences Center" for ISS payload control operations. After substantial remodelling, mainly with new technologies not available in 1998, ISS flight control moved into the totally-revamped FCR 1 in October 2006, due to the growth of the ISS and the international cooperation required among national control centers around the world.

Other facilities

Other MCC facilities include the Training Flight Control Room, sometimes referred to as the Red FCR; a training area for flight controllers; a Life Sciences Control Room used to oversee various experiments; and an Exploration Planning Operations Center used to test new concepts for operations beyond low-Earth orbit. Additionally, there are multi-purpose support rooms. These aid flight controllers by analyzing data and running simulations as well as providing information and advise for the flight controllers.

Building 30 was named for Kraft on April 14, 2011.[1]

Console positions

Mercury Control Center (1960-1963)

During the early years at Cape Canaveral, the original MCC consisted only of three rows, as the Mercury capsule was simple in design and construction, with missions lasting no more than 35 hours.

The first row consisted of several controllers, the BOOSTER, SURGEON, CAPCOM, RETRO, FIDO, and GUIDO.

The BOOSTER controller, depending upon the type of rocket being used, was either a engineer from the Marshall Space Flight Center (for Mercury-Redstone flights) or an Air Force engineer (for Mercury-Atlas and later Gemini-Titan flights) assigned for that mission. The BOOSTER controller's job would last no more than six hours total and he would vacate his console after the booster was jettisoned.

The SURGEON controller, consisting of a flight surgeon (either a military or civilian doctor), monitored the astronaut's vital signs during the flight, and if a medical need arose, could recommend treatment. The CAPCOM controller, filled by an astronaut, maintained nominal air-to-ground communications between the MCC and the orbiting spacecraft; the exception being the SURGEON or Flight Director, and only in an emergency.

The RETRO, FIDO, and GUIDO controllers monitored spacecraft trajectory and handled course changes.

The second row also consisted of several controllers, the ENVIRONMENTAL, PROCEDURES, FLIGHT, SYSTEMS, and NETWORK. The ENVIRONMENTAL controller, later called EECOM, oversaw the consumption of spacecraft oxygen and monitored pressurization, while the SYSTEMS controller, later called EGIL, monitored all other spacecraft systems, including electrical consumption. The PROCEDURES controller, first held by Gene Kranz, handled the writing of all mission milestones, "GO/NO GO" decisions, and synchronized the MCC with the launch countdowns and the Eastern Test Range. The PROCEDURES controller also handled communications, via teletype, between the MCC and the worldwide network of tracking stations and ships.

The flight director, known as FLIGHT, was ultimate supervisor of the Mission Control Center, and gave the final orbit entrance/exit, and, in emergencies, mission abort decisions. During Mercury missions, this position was held by Christopher Kraft, with John Hodge, an Englishman who came to NASA after the cancellation of the Canadian Avro Arrow project, joining the flight director ranks for the 22-orbit Mercury 9, requiring Kraft to divide Mission Control into two shifts. The flight director's console was also the only position in the Cape MCC to have a television monitor, allowing him to see the rocket lift off from the pad. The NETWORK controller, an Air Force officer, served as the "switchboard" between the MCC, the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland (as on-site real-time computing did not exist), and the worldwide tracking station and ship network.

The back row, consisting primarily of NASA and Department of Defense (DOD) management, was the location of the operations director (held by Walt Williams), a general or flag officer who could coordinate with the DOD on all search-and-rescue mission, and the PAO ("Shorty" Powers during Mercury), who provided minute-by-minute mission commentary for the news media and public.

In addition to the controllers in the Cape MCC, each of the manned tracking stations and the Rose Knot Victor and Coastal Sentry Quebec tracking ships, had three controllers, a CAPCOM, SURGEON, and an engineer. Unlike the Cape CAPCOM, which was always staffed by an astronaut, the tracking station/tracking ship CAPCOMs were either a NASA engineer, or an astronaut, with the latter located at stations deemed "critical" by the flight director and operations director.

MOCR (1965-1998)

MOCR 2 during Gemini 5 in 1965

MOCR 2 during Gemini 5 in 1965

After the move from the Cape MCC to the Houston MCC in 1965, the new MOCRs, which were larger and more sophisticated than the single Cape MCC, consisted of four rows, with the first row, later known as "the Trench" (a term coined by Apollo-era RETRO controller John Llewellyn, which, according to Flight Director Eugene Kranz, reminded him of the firing range during his years as a U.S. Marine). It was occupied by the BOOSTER, RETRO, FIDO, and GUIDO controllers. During Gemini, the BOOSTER position was handled by both an engineer from Martin Marietta and an astronaut, while all flights since Apollo 7 used engineers from the Marshall Space Flight Center. The second row, after Project Gemini, consisted of the SURGEON, EECOM, and CAPCOM. The EECOM, which replaced the ENVIRONMENTAL controller and some of the SYSTEMS controller's functions, monitored the spacecraft's electrical and environmental systems. Like the CAPCOMs during Mercury, all CAPCOMs in the Houston MCC are astronauts.

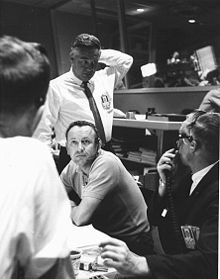

MOCR 1 during the Apollo 13 crisis

MOCR 1 during the Apollo 13 crisis

On the other side of the aisle of the second row were controllers who monitored specific parts of Gemini, Apollo, Skylab, ASTP and Space Shuttle missions. During the Gemini program, the two Agena controllers monitored the Agena upper stage used as a docking target from Gemini 8 through Gemini 12. For the Apollo lunar flights, the TELMU and CONTROL controllers monitored the Lunar Module. During Skylab, the EGIL (pronounced "eagle") monitored Skylab's solar panels, while the EXPERIMENTS controller monitored experiments and the telescopes in the Apollo Telescope Mount. The PAYLOAD and EXPERIMENTS controllers monitor Space Shuttle operations. Another controller, the INCO, monitors the spacecraft's communications and instrumentation.

The third row consisted of the PAO, PROCEDURES, and the FAO (flight activities officer), who coordinated with the flight schedule. The AFD (assistant flight director) and the flight director were also located on the third row.

The fourth row, like the old Cape MCC's third row, was reserved for NASA management, including the director of the Johnson Space Center, the director of flight operations, the director of flight crew operations (chief astronaut), and the Department of Defense officer.

Blue FCR (1998–2006)

The Blue FCR, used primarily for ISS operations from 1998–2006, was arranged in five rows of three consoles, plus one in the rear right corner. From left to right, as viewed from the rear of the room, the front row consisted of ADCO, THOR, and PHALCON.

The second row consisted of OSO, ECLSS pronounced "eekliss", and ROBO.

The third row consisted of ODIN, depending on phase of flight, either ACO (shuttle docked) or the CIO (Free-flight Operations) and OpsPlan.

The fourth row consisted of CATO, FLIGHT—the flight director, and CAPCOM.

Th fiftt last row consisted of GC, depending on the phase of flight; either, RIO, EVA, VVO, or FDO (reboosts only), and finally, SURGEON.

In the back, right corner, behind the surgeon, the PAO (Public Affairs Officer) was occasionally present.

White FCR (1998–2011)

The White FCR during STS-115 in 2006

The White FCR during STS-115 in 2006

The White FCR, used for Space Shuttle operations, is arranged (from left to right, as viewed from the rear of the room) as follows: the front row (the "Trench") consists of FDO (pronounced "fido"), responsible for orbital guidance and orbital changes, depending on the phase of flight, either Guidance, a specialist in the procedures of those two high-energy, fast-paced phases of flight or rendezvous, a specialist in orbital rendezvous procedures; and GC, the controller responsible for the computers and systems in MCC itself.

The second row has PROP, responsible for the propulsion system, GNC, responsible for systems that determine the spacecraft's attitude and issue commands to control it, MMACS (pronounced "max"), responsible for the mechanical systems on the space craft, including the shuttle's robot arm, and EGIL (pronounced "eagle"), responsible for the fuel cells, electrical distribution and O2 & H2 supplies.

The third row has DPS (pronounced "dips"), responsible for the computer systems, ACO, responsible for all payload-related activities, FAO, responsible for the overall plans of activities for the entire flight, and EECOM responsible for the management of environmental systems.

The fourth row has INCO, responsible for communications systems for uploading all systems commands to the vehicle, FLIGHT—the Flight Director, the person in charge of the flight, CAPCOM, an astronaut who is normally the only controller to talk to the astronauts on board, and PDRS, responsible for robot arm operations.

The back row contains PAO (Public Affairs Officer), the "voice" of MCC; MOD, a management representative, depending on the phase of flight, either RIO—only for MIR flights, a Russian-speaker who spoke with the Russian MCC, known as Цуп, (Tsup); BOOSTER responsible for the SRBs and the SSMEs during ascent, or EVA responsible for space suit systems and EVA tasks; and finally, SURGEON.

FCR 1 (2006-present)

All US International Space Station operations are currently controlled from FCR 1, remodeled in 2006. This FCR abandoned the traditional tiered floor layout, with all rows instead at the same level. A few engineering specialists are in the center of the front row, with the public affairs commentator at the right end behind a low partition. The space station trajectory position was moved to the third row.

It also features a new area, known as Gemini, which has reduced staffing for real-time ISS support by consolidating six system disciplines into two positions. From these two "super-consoles", named Atlas and Titan, two people can do the work of up to eight other flight controllers during low-activity periods.[5]

One position, call sign TITAN (Telemetry, Information Transfer, and Attitude Navigation), is responsible for Communication & Tracking (CATO), Command & Data Handling (ODIN), and Motion Control Systems (ADCO).

The other position, call sign ATLAS (Atmosphere, Thermal, Lighting and Articulation Specialist), is responsible for Thermal Control (THOR), Environmental Control & Life Support (ECLSS), and Electrical Power Systems (PHALCON). ATLAS is also responsible for monitoring Robotics (ROBO) and Mechanical Systems (OSO) heaters, as those consoles are not supported during the majority of Gemini shifts.[5]

See also

- Flight controller

- Mission control center

- Launch status check

- Control center solutions

Notes

- ^ a b http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/shuttle/behindscenes/kraft_mcc.html

- ^ Mercury Control building

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2008-04-15. http://nrhp.focus.nps.gov/natreg/docs/All_Data.html.

- ^ "Apollo Mission Control Center- Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms: A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary". Nps.gov. http://www.nps.gov/nr//travel/aviation/apo.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- ^ a b Oberg, James "NASA’s Newest Flight Control Room" (October 22, 2006) spaceflight.com

References

External links

- NASA's MCC page

- MCC history

- National Park Service Mission Control page

- Aerospace-Technology.com Mission Control article

U.S. National Register of Historic Places Topics Lists by states Alabama • Alaska • Arizona • Arkansas • California • Colorado • Connecticut • Delaware • Florida • Georgia • Hawaii • Idaho • Illinois • Indiana • Iowa • Kansas • Kentucky • Louisiana • Maine • Maryland • Massachusetts • Michigan • Minnesota • Mississippi • Missouri • Montana • Nebraska • Nevada • New Hampshire • New Jersey • New Mexico • New York • North Carolina • North Dakota • Ohio • Oklahoma • Oregon • Pennsylvania • Rhode Island • South Carolina • South Dakota • Tennessee • Texas • Utah • Vermont • Virginia • Washington • West Virginia • Wisconsin • WyomingLists by territories Lists by associated states Other Spaceflight National Historic Landmarks Alabama Neutral Buoyancy Space Simulator · Propulsion and Structural Test Facility · Redstone Test Stand · Saturn V Launch Vehicle · Saturn V Dynamic Test Stand

Florida Arizona California Mississippi New Mexico Ohio Zero Gravity Research FacilityTexas Apollo Mission Control Center · Space Environment Simulation LaboratoryCategories:- National Historic Landmarks in Texas

- Buildings and structures completed in 1965

- Buildings and structures in Texas

- Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center

- NASA facilities

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.