- Cholera outbreaks and pandemics

-

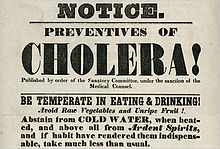

Hand bill from the New York City Board of Health, 1832. The outdated public health advice demonstrates the lack of understanding of the disease and its actual causative factors.

Hand bill from the New York City Board of Health, 1832. The outdated public health advice demonstrates the lack of understanding of the disease and its actual causative factors.

It is estimated that cholera affects 3-5 million people worldwide, and causes 100,000-130,000 deaths a year as of 2010.[1] This occurs mainly in the developing world.[2] In the early 1980s, death rates are believed to have been greater than 3 million a year.[3] It is difficult to calculate exact numbers of cases, as many go unreported due to concerns that an outbreak may have a negative impact on the tourism of a country.[4] Cholera remains both epidemic and endemic in many areas of the world.[3]

Although much is known about the mechanisms behind the spread of cholera, this has not led to a full understanding of what makes cholera outbreaks happen some places and not others. Lack of treatment of human feces and lack of treatment of drinking water greatly facilitate its spread, but bodies of water can serve as a reservoir, and seafood shipped long distances can spread the disease. Cholera was not known in the Americas for most of the 20th century, but it reappeared towards the end of that century and seems likely to persist.[5]

Deaths in India between 1817 and 1860 are estimated to have exceeded 15 million people. Another 23 million died between 1865 and 1917. Russian deaths during a similar time period exceeded 2 million.[6]

Contents

Pandemics

First

- 1816-1826 - The first cholera pandemic, though previously restricted, began in Bengal, and then spread across India by 1820. Ten thousand British troops, and many times this number of Indians, died during this pandemic.[7] The cholera outbreak extended as far as China, Indonesia (where more than 100,000 people succumbed on the island of Java alone) and the Caspian Sea, before receding.

Second

- 1829-1851 - A second cholera pandemic reached Russia (see Cholera Riots), Hungary (about 100,000 deaths) and Germany in 1831, London (more than 55,000 people died in the United Kingdom)[8] and Paris in 1832. In London, the disease claimed 6,536 victims and came to be known as "King Cholera"; in Paris, 20,000 succumbed (out of a population of 650,000), with about 100,000 deaths in all of France.[9] The epidemic reached Quebec, Ontario and New York in the same year, and the Pacific coast of North America by 1834. In the center of the country, it spread through the cities linked by the rivers and steamboat traffic.[10] The 1831 cholera epidemic killed 150,000 people in Egypt.[11]

- In 1846, cholera struck Mecca, killing over 15,000 people.[12] A two-year outbreak began in England and Wales in 1848, and claimed 52,000 lives.[13]

- 1849 - A second major outbreak occurred in Paris. In London, it was the worst outbreak in the city's history, claiming 14,137 lives, over twice as many as the 1832 outbreak. Cholera hit Ireland in 1849 and killed many of the Irish Famine survivors, already weakened by starvation and fever.[14] In 1849, cholera claimed 5,308 lives in the port city of Liverpool, England, and 1,834 in Hull, England.[9] An outbreak in North America took the life of former U.S. President James K. Polk. Cholera, believed spread from ship(s) from England, spread throughout the Mississippi river system, killing over 4,500 in St. Louis[9] and over 3,000 in New Orleans[9] as well as thousands in New York.[9] It claimed 200,000 victims in Mexico.[15]

- In 1849, cholera was spread along the California, Mormon and Oregon Trails as 6,000 to 12,000[16] are believed to have died on their way to the California Gold Rush, Utah and Oregon in the cholera years of 1849-1855.[9] It is believed more than 150,000 Americans died during the two pandemics between 1832 and 1849.[17][18]

- [19] During this pandemic the beliefs behind the reason for cholera differed. In France cholera was assumed to somehow be connected to the poor community or the environment. Russia thought of this disease as contagious and America put the blame of cholera on recent immigrants, specifically the Irish. Lastly, some of the British thought that the reason might be due to divine intervention.:[19]

Third

- 1852-1860 - The third cholera pandemic mainly affected Russia, with over one million deaths. In 1852, cholera spread east to Indonesia, and later invaded China and Japan in 1854. The Philippines were infected in 1858 and Korea in 1859. In 1859, an outbreak in Bengal again led to the transmission of the disease to Iran, Iraq, Arabia and Russia.[12] There were at least seven major outbreaks of cholera in Japan between 1858 and 1902. The Ansei outbreak of 1858-60, for example, is believed to have killed between 100,000 and 200,000 people in Tokyo alone.[20]

- 1854 - An outbreak of cholera in Chicago took the lives of 5.5% of the population (about 3,500 people).[9][21] In 1853-4, London's epidemic claimed 10,738 lives. The Soho outbreak in London ended after removal of the handle of the Broad Street pump by a committee instigated to action by John Snow.[22] His study proved contaminated water was the main agent spreading cholera, although he did not identify the contaminant. It would take many years for this message to be believed and acted upon. Throughout Spain, cholera caused more than 236,000 deaths in 1854–55.[23] In 1854 and 1855, it entered Venezuela; Brazil also suffered in 1855.[15]

During the third pandemic, Tunisia, who had not been affected by the two previous pandemics thought the reason for choler was the Europeans. They blamed the sanitation of the Europeans who had previously had the disease and were in their country. Also, the United States now assumed that cholera was somehow associated with African Americans :[24]

Fourth

- 1863-1875 - The fourth cholera pandemic spread mostly in Europe and Africa. At least 30,000 of the 90,000 Mecca pilgrims fell victim to the disease. Cholera ravaged Africa in 1865. Traveling southeastward, cholera reached Zanzibar, where 70,000 people are reported to have died in 1869–70.[25] Cholera claimed 90,000 lives in Russia in 1866.[26] The epidemic of cholera that spread with the Austro-Prussian War (1866) is estimated to have taken 165,000 lives in the Austrian Empire.[27] Hungary and Belgium both lost 30,000 people, and in the Netherlands, 20,000 perished. In 1867, Italy lost 113,000 lives.[28] That same year, cholera traveled to Algeria and killed 80,000.[25]

- Outbreaks in North America in 1866 - 1873 killed some 50,000 Americans.[17]

- In London, a localized epidemic in the East End claimed 5,596 lives, just as London was completing its major sewage and water treatment systems; the East End section was not quite complete. William Farr, using the work of John Snow, et al., as to contaminated drinking water being the likely source of the disease, relatively quickly identified the East London Water Company as the source of the contaminated water. Quick action prevented further deaths.[9] Also, a minor outbreak occurred at Ystalyfera in South Wales, caused by the local water works using contaminated canal water; it was mainly its workers and their families who suffered, and 119 died. In the same year, more than 21,000 people died in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. In the 1870s, cholera spread in the U.S. as an epidemic from New Orleans along the Mississippi River and related ports of tributaries, with thousands dying.

Fifth

- 1881-1896 - The fifth cholera pandemic, according to Dr A. J. Wall, the 1883-1887 part of the epidemic cost 250,000 lives in Europe and at least 50,000 in Americas. Cholera claimed 267,890 lives in Russia (1892);[29] 120,000 in Spain;[30] 90,000 in Japan and over 60,000 in Persia.[29] In Egypt, cholera claimed more than 58,000 lives. The 1892 outbreak in Hamburg killed 8,600 people. Although the city government was generally held responsible for the virulence of the epidemic, it went largely unchanged. This was the last serious European cholera outbreak, as cities improved their sanitation and water systems.

Sixth

- 1899-1923 - The sixth cholera pandemic had little effect in Europe because of advances in public health, but major Russian cities (more than 500,000 people dying of cholera during the first quarter of the 20th century)[31] and the Ottoman Empire were particularly hard hit by cholera deaths. The 1902-1904 cholera epidemic claimed 200,000 lives in the Philippines.[32] Twenty-seven epidemics were recorded during pilgrimages to Mecca from the 19th century to 1930, and more than 20,000 pilgrims died of cholera during the 1907–08 hajj.[31] The sixth pandemic killed more than 800,000 in India. The last outbreak in the United States was in 1910-1911, when the steamship Moltke brought infected people from Naples to New York City. Vigilant health authorities isolated the infected on Swinburne Island. Eleven people died, including a health care worker on the island.[33][34][35]

- In this time period cholera greatly started to be associated with outsiders and this could be seen time and time again. The Italians blamed the Jews and gypsies, the British who were in India accused the “dirty natives”, and the Americans saw the problem coming from the Philippines.[36]

Seventh

- 1961–1975 - The seventh cholera pandemic began in Indonesia, called El Tor[3] after the strain, and reached East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in 1963, India in 1964, and the USSR in 1966. From North Africa, it spread into Italy by 1973. In the late 1970s, there were small outbreaks in Japan and in the South Pacific. There were also many reports of a cholera outbreak near Baku in 1972, but information about it was suppressed in the USSR.[citation needed]

Notable recent outbreaks

- 2011: Besides the ongoing cholera outbreak in Haiti and spilling over to Dominican Republic, there are outbreaks in Nigeria and Democratic Republic of Congo, in addition, Somalia is experiencing a double hit of cholera outbreak and famine.[37]

- In January 2011, about 411 Venezuelan citizens were invited to a wedding ceremony to be held in The Dominican Republic, by the time they returned to Caracas and other Venezuelan cities, some of these people, all of whom had consumed a particular dish of raw fish cooked in lemon juice, (Ceviche), were suffering from the symptoms of Cholera. By January 28, almost 111 cases had been confirmed by the Venezuelan Health Authorities, who as a safety measure quickly instituted an 800 number for patients who were in doubt as to whether or not they too were infected. Internationally, this small outbreak prompted Venezuela's western neighbor, Colombia, to secure its border against probable transmission and immigration of the disease. Also, Dominican authorities started a nationwide study to determine the cause of the outbreak within their shores, as well as warning the public of the imminent danger associated to the consumption of raw fish and shellfish. As of January 29, 2011, none of the cases in Venezuela proved fatal, but 2 of them degraded to a life-threatening state and the patients had to be hospitalized. The fact that most of the people infected were members of the upper class probably helped in speeding up the detection and containment of the outbreak, since most of them had a way to circumvent Venezuela's deteriorated public health facilities, and had access to private clinics and hospitals.[38]

- November 2010 - It was reported the cholera outbreak that began in Haiti the previous month had spread into the Dominican Republic. Nepalese UN soldiers have been blamed for acting as carriers and passing it on through poorly maintained septic systems. However, Asian cholera strains have been spread around the world already e.g. by ballast water of ships; Vibrio cholera bacteria can survive between outbreaks in brackish warm water as it recently has been discovered, and movement of unresistant refugees near this is the likely cause.,.[39][40] It was also reported the cholera outbreak has reached Florida from a woman who had visited Haiti.[41] Cholera has occurred in Southern USA in recent years without causing major epidemics.[42]

- October 2010 - In late October a cholera outbreak was reported in Haiti,[43] and as of November 16 the Haitian Health Ministry reported the number of dead to be 1,034, with hospitalizations for cholera symptoms totaling over 16,700.[44] It is feared that the epidemic could accelerate due to standing water left by a recent hurricane and the fact that over one-tenth of the population remain living in close quarters in tents in refugee camps without adequate sanitation since the Haiti earthquake in January.[45]

- August 2010 - Nigeria is reaching epidemic proportions after wide spread confirmation of the Cholera outbreaks in 12 of its 36 states. 6400 cases have been reported with 352 reported deaths. The health ministry blamed the outbreak on heavy seasonal rainfall and poor sanitation.[46]

- January 2009 - The Mpumalanga province of South Africa has confirmed over 381 new cases of Cholera, bringing the total number of cases treated since November 2008 to 2276. 19 people have died in the province since the outbreak.[47]

- August 2008 - April 2009: In the 2008 Zimbabwean cholera outbreak,[48] which is still continuing, an estimated 96,591 people in the country have been infected with cholera and, by 16 April 2009, 4,201 deaths had been reported.[49] According to the World Health Organization, during the week of 22–28 March 2009, the "Crude Case Fatality Ratio (CFR)" had dropped from 4.2% to 3.7%.[49] The daily updates for the period 29 March 2009 to 7 April 2009, list 1748 cases and 64 fatalities, giving a weekly CFR of 3.66% (see table above);[50] however, those for the period 8 April to 16 April list 1375 new cases and 62 deaths (and a resulting CFR of 4.5%).[50] The CFR had remained above 4.7% for most of January and early February 2009.[51]

- November 2008 - Doctors Without Borders reported an outbreak in a refugee camp in the Democratic Republic of the Congo's eastern provincial capital of Goma.[52] Some 45 cases were reportedly treated between November 7 and 9.

- August - October 2008 - As of 29 October 2008, a total of 644 laboratory-confirmed cholera cases, including eight deaths, had been verified in Iraq.[53]

- March - April 2008 - 2,490 people from 20 provinces throughout Vietnam have been hospitalized with acute diarrhea. Of those hospitalized, 377 patients tested positive for cholera.[54]

- August 2007 - The cholera epidemic started in Orissa, India. The outbreak has affected Rayagada, Koraput and Kalahandi districts, where more than 2,000 people have been admitted to hospitals.[55]

- July - December 2007 - A lack of clean drinking water in Iraq has led to an outbreak of cholera.[56][57] As of 2 December 2007, the UN had reported 22 deaths and 4,569 laboratory-confirmed cases.[58]

- In 2000, some 140,000 cholera cases were officially notified to WHO. Africa accounted for 87% of these cases.[59]

- January 1991 to September 1994 - Outbreak in South America, apparently initiated when a ship discharged ballast water. Beginning in Peru,[60] there were 1.04 million identified cases and almost 10,000 deaths. The causative agent was an O1, El Tor strain, with small differences from the seventh pandemic strain. In 1992 a new strain appeared in Asia, a non-O1, nonagglutinable vibrio (NAG) named O139 Bengal. It was first identified in Tamil Nadu, India and for a while displaced El Tor in southern Asia before decreasing in prevalence from 1995 to around 10% of all cases. It is considered to be an intermediate between El Tor and the classic strain and occurs in a new serogroup. There is evidence of the emergence of wide-spectrum resistance to drugs such as trimethoprim, sulfamethoxazole and streptomycin.

False reports

A persistent myth states 90,000 people died in Chicago of cholera and typhoid fever in 1885, but this story has no factual basis.[61] In 1885, there was a torrential rainstorm that flushed the Chicago River and its attendant pollutants into Lake Michigan far enough that the city's water supply was contaminated. However, because cholera was not present in the city, there were no cholera-related deaths. Nevertheless, the incident caused the city to become more serious about its sewage treatment.

See also

References

- ^ "Cholera vaccines. A brief summary of the March 2010 position paper" (pdf). World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/immunization/Cholera_PP_Accomp_letter__Mar_10_2010.pdf.

- ^ Reidl J, Klose KE (June 2002). "Vibrio cholerae and cholera: out of the water and into the host". FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 26 (2): 125–39. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2002.tb00605.x. PMID 12069878.

- ^ a b c Sack DA, Sack RB, Nair GB, Siddique AK (January 2004). "Cholera". Lancet 363 (9404): 223–33. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15328-7. PMID 14738797.

- ^ Sack DA, Sack RB, Chaignat CL (August 2006). "Getting serious about cholera". N. Engl. J. Med. 355 (7): 649–51. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068144. PMID 16914700.

- ^ Blake, PA (1993). "Epidemiology of cholera in the Americas.". Gastroenterology clinics of North America 22 (3): 639–60. PMID 7691740.

- ^ Beardsley GW (2000). "The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State: 19th Century Responses to Cholerae Vibrio (part 1)". The Early America Review 3 (2). http://www.earlyamerica.com/review/2000_fall/1832_cholera_part1.html. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Pike J (2007-10-23). "Cholera- Biological Weapons". Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD). GlobalSecurity.com. http://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/intro/bio_cholera.htm. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Asiatic Cholera Pandemic of 1826-37

- ^ a b c d e f g h Charles E. Rosenberg (1987). The cholera years: the United States in 1832, 1849 and 1866. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-72677-0.

- ^ Wilford JN (2008-04-15). "How Epidemics Helped Shape the Modern Metropolis". New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/15/science/15chol.html?_r=1&8dpc. Retrieved 2010-02-01. "On a Sunday in July 1832, a fearful and somber crowd of New Yorkers gathered in City Hall Park for more bad news. The epidemic of cholera, cause unknown and prognosis dire, had reached its peak."

- ^ Cholera Epidemic in Egypt (1947).

- ^ a b Asiatic Cholera Pandemic of 1846-63. UCLA School of Public Health.

- ^ Cholera's seven pandemics, cbc.ca, December 2, 2008.

- ^ The Irish Famine.

- ^ a b Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 101. ISBN 0313341028. http://books.google.com/books?id=5Pvi-ksuKFIC&pg=PA101&dq#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ Unruh, John David (1993). The plains across: the overland emigrants and the trans-Mississippi West, 1840-60. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. pp. 408–10. ISBN 0-252-06360-0.

- ^ a b Beardsley GW (2000). "The 1832 Cholera Epidemic in New York State: 19th Century Responses to Cholerae Vibrio (part 2)". The Early America Review 3 (2). http://www.earlyamerica.com/review/2000_fall/1832_cholera_part2.html. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Vibrio cholerae in recreational beach waters and tributaries of Southern California.

- ^ a b Hayes, J.N. (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 214–219.

- ^ "Local agrarian societies in colonial India: Japanese perspectives.". Kaoru Sugihara, Peter Robb, Haruka Yanagisawa (1996). p 313.

- ^ Chicago Daily Tribune, 12 Jul 1854

- ^ Snow, John (1855). On the Mode of Communication of Cholera. http://eee.uci.edu/clients/bjbecker/PlaguesandPeople/week8a.html.

- ^ Kohn, George C. (2008). Encyclopedia of plague and pestilence: from ancient times to the present. Infobase Publishing. p. 369. ISBN 0816069352. http://books.google.com/books?id=tzRwRmb09rgC&pg=PA369&dq#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ Hayes, J.N. (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 233.

- ^ a b Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 107. ISBN 0313341028. http://books.google.com/books?id=5Pvi-ksuKFIC&pg=PA107&dq#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ^ Eastern European Plagues and Epidemics 1300-1918.

- ^ Impact of infectious diseases on war. Matthew R. Smallman-Raynor PhD and Andrew D. Cliff DSc [1].

- ^ Vibrio Cholerae and Cholera - The History and Global Impact.

- ^ a b Cholera (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 265. http://www.archive.org/stream/encyclopaediabrit06chisrich#page/265/mode/1up/. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ "The cholera in Spain". New York Times. 1890-06-20. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=9E05EED7123BE533A25753C2A9609C94619ED7CF. Retrieved 2008-12-08.

- ^ a b "Cholera (pathology): Seven pandemics". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/114078/cholera/253250/Seven-pandemics. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ 1900s: The Epidemic years, Society of Philippine Health History.

- ^ "Cholera Kills Boy. All Other Suspected Cases Now in Quarantine and Show No Alarming Symptoms." (PDF). New York Times. July 18, 1911. http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?res=990CEFD61431E233A2575BC1A9619C946096D6CF. Retrieved 2008-07-28. "The sixth death from cholera since the arrival in this port from Naples of the steamship Moltke, thirteen days ago, occurred yesterday at Swineburne Island. The victim was Francesco Farando, 14 years old."

- ^ "More Cholera in Port". Washington Post. October 10, 1910. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/washingtonpost_historical/access/250061412.html?dids=250061412:250061412&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&date=OCT+10%2C+1910&author=&pub=The+Washington+Post&desc=MORE+CHOLERA+IN+PORT&pqatl=google. Retrieved 2008-12-11. "A case of cholera developed today in the steerage of the Hamburg-American liner Moltke, which has been detained at quarantine as a possible cholera carrier since Monday last. Dr. A.H. Doty, health officer of the port, reported the case tonight with the additional information that another cholera patient from the Moltke is under treatment at Swinburne Island."

- ^ The Boston Medical and Surgical journal. Massachusetts Medical Society. 1911. http://books.google.com/?id=0NQEAAAAYAAJ&pg=PP281&lpg=PP281&dq=cholera+1910+moltke. "In New York, up to July 22, there were eleven deaths from cholera, one of the victims being an employee at the hospital on Swinburne Island, who had been discharged. The tenth was a lad, seventeen years of age, who had been a steerage passenger on the steamship, Moltke. The plan has been adopted of taking cultures from the intestinal tracts of all persons held under observation at Quarantine, and in this way it was discovered that five of the 500 passengers of the Moltke and Perugia, although in excellent health at the time, were harboring cholera microbes."

- ^ Hayes, J.N. (2005). Epidemics and Pandemics: Their Impacts on Human History. Santa Barbara CA: ABC-CLIO. pp. 349.

- ^ http://www.bendbulletin.com/article/20110813/NEWS0107/108130383/

- ^ http://www.wral.com/lifestyles/healthteam/story/9020742/

- ^ . http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/us/Nepali-peacekeepers-not-responsible-for-cholera-in-Haiti-UN/articleshow/6953120.cm.[dead link]

- ^ http://www.circleofblue.org/waternews/2010/world/hold-cholera-in-haiti-the-climate-connection

- ^ http://www.orlandosentinel.com/health/os-cholera-case-orange-county-20101129,0,6507687.story

- ^ . PMID 7691740.

- ^ "Haiti’s Latest Misery". The New York Times. 26 October 2010. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/27/opinion/27wed2.html. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Official: Cholera death toll in Haiti has passed 1,000". Associated Press. msnbc.com. 16 November 2010. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/40216940/. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "Haiti cholera death toll over 500". The Straits Times. AFP. 7 November 2010. http://www.straitstimes.com/BreakingNews/World/Story/STIStory_600290.html. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ Cholera epidemic death toll rises to 352, MSNBC, 25 August 2010.

- ^ 381 new cholera cases in Mpumalanga, News24, 24 January 2009.

- ^ "Zimbabwe: Cholera Outbreak Kills 294". The New York Times. Associated Press. 22 November 2008. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9E02E4D61739F931A15752C1A96E9C8B63. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ a b World Health Organization. Cholera in Zimbabwe: Epidemiological Bulletin Number 16 Week 13 (22-28 March 2009). March 31, 2009.; WHO Zimbabwe Daily Cholera Update, 16 April 2009.

- ^ a b World Health Organization: Zimbabwe Daily Cholera Updates.

- ^ Mintz & Guerrant 2009

- ^ Sky News Doctors Fighting Cholera In Congo.

- ^ "Situation report on diarrhoea and cholera in Iraq". ReliefWeb. 2008-10-29. http://www.reliefweb.int/rw/rwb.nsf/db900sid/SHIG-7KWHHY?OpenDocument. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Cholera Country Profile: Vietnam. WHO.

- ^ Jena S (2007-08-29). "Cholera death toll in India rises". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6968281.stm. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ James Glanz; Denise Grady (12 September 2007). "Cholera Epidemic Infects 7,000 People in Iraq". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2007/09/12/world/middleeast/12iraq.html?_r=1. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ "U.N. reports cholera outbreak in northern Iraq". CNN. 2007-08-30. http://www.cnn.com/2007/WORLD/meast/08/29/iraq.cholera/index.html. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Smith D (2007-12-02). "Cholera crisis hits Baghdad". The Observer (London). http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2007/dec/02/iraq.davidsmith. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

- ^ Disease fact sheet: Cholera. IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre.

- ^ Nathaniel C. Nash (10 March 1992). "Latin Nations Feud Over Cholera Outbreak". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/10/world/latin-nations-feud-over-cholera-outbreak.html?scp=3&sq=cholera%20outbreak%20peru%201992&st=cse. Retrieved 16 February 2011.

- ^ "Did 90,000 people die of typhoid fever and cholera in Chicago in 1885?". The Straight Dope. 2004-11-12. http://www.straightdope.com/columns/041112.html. Retrieved 2010-02-01.

Categories:- Gastroenterology

- Intestinal infectious diseases

- Bacterial diseases

- Pandemics

- Neglected diseases

- Microbiology

- Cholera

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.