- Charles James Fox

-

The Right Honourable

Charles James Fox

Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs In office

27 March 1782 – 5 July 1782Prime Minister The Marquess of Rockingham Preceded by The Viscount Stormont (Northern Secretary) Succeeded by The Lord Grantham Constituency Midhurst, West Sussex Leader of the House of Commons In office

27 March 1782 – 5 July 1782Prime Minister The Marquess of Rockingham Preceded by Lord North Succeeded by Thomas Townshend Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs In office

2 April 1783 – 19 December 1783Prime Minister The Duke of Portland Preceded by The Lord Grantham Succeeded by The Earl Temple Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs In office

7 February 1806 – 13 September 1806Prime Minister William Grenville Preceded by The Lord Mulgrave Succeeded by Viscount Howick Personal details Born 24 January 1749 Died 13 September 1806 (aged 57)

Chiswick, EnglandPolitical party British Whig Party Spouse(s) Elizabeth Armistead Profession Statesman, abolitionist Charles James Fox PC (24 January 1749 – 13 September 1806), styled The Honourable from 1762, was a prominent British Whig statesman whose parliamentary career spanned thirty-eight years of the late 18th and early 19th centuries and who was particularly noted for being the arch-rival of William Pitt the Younger. The son of an old, indulgent Whig father, Fox rose to prominence in the House of Commons as a forceful and eloquent speaker with a notorious and colourful private life, though his opinions were rather conservative and conventional. However, with the coming of the American Revolution and the influence of the Whig Edmund Burke, Fox's opinions evolved into some of the most radical ever to be aired in the Parliament of his era. He came from a family with radical and revolutionary tendencies and his first cousin and friend Lord Edward Fitzgerald was a prominent member of the Society of United Irishmen who was arrested just prior to the Irish Rebellion of 1798 and died of wounds received as he was arrested.

Fox became a prominent and staunch opponent of George III, whom he regarded as an aspiring tyrant; he supported the revolutionaries across the Atlantic, taking up the habit of dressing in the colours of George Washington's army. Briefly serving as Britain's first Foreign Secretary in the ministry of the Marquess of Rockingham in 1782, he returned to the post in a coalition government with his old enemy Lord North in 1783. However, the King forced Fox and North out of government before the end of the year, replacing them with the twenty-four-year-old Pitt the Younger, and Fox spent the following twenty-two years facing Pitt and the government benches from across the Commons.

Though Fox had little interest in the actual exercise of power[1] and spent almost the entirety of his political career in opposition, he became noted as an anti-slavery campaigner, a supporter of the French Revolution, and a leading parliamentary advocate of religious tolerance and individual liberty. His friendship with his mentor Burke and his parliamentary credibility were both casualties of Fox's support for France during the Revolutionary Wars, but he went on to attack Pitt's wartime legislation and to defend the liberty of religious minorities and political radicals. After Pitt's death in January 1806, Fox served briefly as Foreign Secretary in the 'Ministry of All the Talents' of William Grenville, before he died on 13 September 1806, aged fifty-seven.

1749–1758: Early life

Fox was born at 9 Conduit Street,[2] London, the second surviving son of Henry Fox, 1st Baron Holland and Lady Caroline Lennox, a daughter of Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond.[3] The father Lord Holland (1705–1774) was an ally of Robert Walpole and rival of Pitt the Elder. He had amassed a considerable fortune by exploiting his position as Paymaster General of the forces. Fox's elder brother, Stephen (1745–1774) became 2nd Baron Holland. His younger brother, Henry (1755–1811), had a distinguished military career.[4]

Fox was the darling of his father, who found Charles "infinitely engaging & clever & pretty" and, from the time that his son was three years old, apparently preferred his company at meals to that of anyone else.[5] The stories of Charles's over-indulgence by his doting father are legendary. It was said that Charles once expressed a great desire to break his father's watch and was not restrained or punished when he duly smashed it on the floor. On another occasion, when Henry had promised his son that he could watch the demolition of a wall on his estate and found that it had already been destroyed, he ordered the workmen to rebuild the wall and demolish it again, with Charles watching.[6]

1758–1768: Education

Given carte blanche to choose his own education, in 1758 Fox attended a fashionable Wandsworth school run by a Monsieur Pampellonne, followed by Eton College, where he began to develop his life-long love of classical literature. In later life he was said always to have carried a copy of Horace in his coat pocket. He was taken out of school by his father in 1761 to attend the coronation of George III, who would become one of his most bitter enemies, and once more in 1763 to visit the Continent; to Paris and Spa. On this trip, Charles was given a substantial amount of money with which to learn to gamble by his father, who also arranged for him to lose his virginity, aged fourteen, to a Madame de Quallens.[4] Fox returned to Eton later that year, "attired in red-heeled shoes and Paris cut-velvet, adorned with a pigeon-wing hair style tinted with blue powder, and a newly acquired French accent", and was duly flogged by Dr. Barnard, the headmaster.[7] These three pursuits – gambling, womanising and the love of things and fashions foreign – would become, once inculcated in his adolescence, notorious habits of Fox’s later life.

Fox entered Hertford College, Oxford, in October 1764, although he would later leave without taking a degree, rather contemptuous of its "nonsenses".[8] He went on several further expeditions to Europe, becoming well known in the great Parisian salons, meeting influential figures such as Voltaire, Edward Gibbon, the duc d'Orléans and the marquis de Lafayette, and becoming the co-owner of a number of racehorses with the duc de Lauzun.[4]

1768–1774: Early political career

For the 1768 general election, Henry Fox bought his son the West Sussex constituency of Midhurst, though Charles was still nineteen and technically ineligible for Parliament. Fox was to address the House of Commons some 254 times between 1768 and 1774[4] and rapidly gathered a reputation as a superb orator, but he had not yet developed the radical opinions for which he would become famous. Thus he spent much of his early years unwittingly manufacturing ammunition for his later critics and their accusations of hypocrisy. A supporter of the Grafton and North ministries, Fox was prominent in the campaign to punish the radical John Wilkes for challenging the Commons. "He thus opened his career by speaking in behalf of the Commons against the people and their elected representative."[9] Consequently, both Fox and his brother, Stephen, were insulted and pelted with mud in the street by the pro-Wilkes London crowds.[10]

However, between 1770 and 1774, Fox's seemingly promising career in the political establishment was spoiled. In February 1770, Fox was appointed to the board of the Admiralty by Lord North, but on the 15th of the same month he resigned due to his enthusiastic opposition to the government's Royal Marriages Act, the provisions of which – incidentally – cast doubt on the legitimacy of his parents' marriage.[4] On 28 December 1772, North appointed Fox to the board of the Treasury and again he surrendered his post, in February 1774, over the Government's allegedly feeble response to the contemptuous printing and public distribution of copies of parliamentary debates. Behind these incidents lay his family's resentment towards Lord North for refusing to elevate the Holland barony to an earldom.[4] But the fact that such a young man could seemingly treat ministerial office so lightly was noted at court. George III, also observing Fox's licentious private behaviour, took it to be presumption and judged that Fox could not be trusted to take anything seriously.[4]

1774–1782: The American Revolution

After 1774, Fox began to reconsider his political position under the influence of Edmund Burke – who had sought out the promising young Whig and would become his mentor – and the unfolding events in America. He drifted from his rather unideological family-orientated politics into the orbit of the Rockingham Whig party.

During this period, Fox became possibly the most prominent and vituperative parliamentary critic of Lord North and the conduct of the American war. In 1775, he denounced North in the Commons as

the blundering pilot who had brought the nation into its present difficulties ... Lord Chatham, the King of Prussia, nay, Alexander the Great, never gained more in one campaign than the noble lord has lost—he has lost a whole continent.[4]Fox, who occasionally corresponded with Thomas Jefferson and had met Benjamin Franklin in Paris,[4] predicted that Britain had little practical hope of subduing the colonies, and interpreted the American cause approvingly as a struggle for liberty against the oppressive policies of a despotic and unaccountable executive.[4] It was at this time that Fox and his supporters took up the habit of dressing in buff and blue: the colours of the uniforms in Washington’s army. Fox's friend, the Earl of Carlisle, observed that any setback for the British Government in America was "a great cause of amusement to Charles."[11] Even after the American defeat at Long Island in 1776, Fox stated that

I hope that it will be a point of honour among us all to support the American pretensions in adversity as much as we did in their prosperity, and that we shall never desert those who have acted unsuccessfully upon Whig principles.[12]On 31 October the same year, Fox responded to the King's address to Parliament with "one of his finest and most animated orations, and with severity to the answered person", so much so that, when he sat down, no member of the Government would attempt to reply.[13]

Also crucial to any understanding of Fox's political career from this point was his mutual antipathy with George III – probably the most enthusiastic prosecutor of the American war. Fox became convinced that the King was determined to challenge the authority of Parliament and the balance of the constitution established in 1688, and to achieve Continental-style tyranny. George in return thought that Fox had "cast off every principle of common honour and honesty ... [a man who is] as contemptible as he is odious ... [and has an] aversion to all restraints."[2] It is difficult to find two figures in history more greatly contrasted in temperament than Fox and George: the former a notorious gambler and rake; the latter famous for his virtues of frugality and family. On 6 April 1780, John Dunning's motion that "The influence of the Crown has increased, is increasing, and ought to be diminished." passed the Commons by a vote of 233 to 215.[14] Fox thought it "glorious", saying on 24 April that

the question now was ... whether that beautiful fabric [i.e. the constitution] ... was to be maintained in that freedom ... for which blood had been spilt; or whether we were to submit to that system of despotism, which had so many advocates in this country.[4]Fox, however, had not been present in the House for the beginning of the Dunning debate, as he had been occupied in the adjoining eleventh-century Westminster Hall, serving as chairman of a mass public meeting before a large banner that read "Annual Parliaments and Equal Representation".[15] This was the period when Fox, hardening against the influence of the Crown, was embraced by the radical movement of the late eighteenth century. When the shocking Gordon riots exploded in London in June 1780, Fox – though deploring the violence of the crowd – declared that he would "much rather be governed by a mob than a standing army."[16] Later, in July, Fox was returned for the populous and prestigious constituency of Westminster, with around 12,000 electors, and acquired the title "Man of the People".[4]

1782–1784: Constitutional crisis

When North finally resigned under the strains of office and the disastrous American war in March 1782 and was gingerly replaced with the new ministry of the Marquess of Rockingham, Fox was appointed Foreign Secretary. But Rockingham, after finally acknowledging the independence of the former Thirteen Colonies, died unexpectedly on 1 July. Fox refused to serve in the successor administration of the Earl of Shelburne, splitting the Whig party; Fox's father had been convinced that Shelburne – a supporter of the elder Pitt – had thwarted his ministerial ambitions at the time of the 1763 peace.[17] Fox now found himself in common opposition to Shelburne with his old and bitter enemy, Lord North. Based on this single conjunction of interests and the fading memory of the happy co-operation of the early 1770s, the two men who had vilified one another throughout the American war together formed a coalition and forced their Government, with an overwhelming majority composed of North's Tories and Fox's opposition Whigs, on to the King.

The Fox-North Coalition came to power on 2 April 1783, in spite of the King's resistance. It was the first time that George had been allowed no role in determining who should hold government office.[4] On one occasion, Fox, who returned enthusiastically to the post of Foreign Secretary, ended an epistle to the King: "Whenever Your Majesty will be graciously pleased to condescend even to hint your inclinations upon any subject, that it will be the study of Your Majesty's Ministers to show how truly sensible they are of Your Majesty's goodness." The King replied: "No answer."[18] George III seriously thought of abdicating at this time, after the comprehensive defeat of his American policy and the imposition of Fox and North,[19] but refrained from doing so, mainly because of the thought of his succession by his son, George Augustus Frederick: the notoriously extravagant womaniser, gambler and associate of Fox, who could swear in three languages.[20] Indeed, in many ways the King considered Fox his son's tutor in debauchery. "George III let it be widely broadcast that he held Fox principally responsible for the Prince’s many failings, not least a tendency to vomit in public."[21]

Happily for George, however, the unpopular coalition would not outlast the year. The Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, formally ending the American Revolutionary War. Fox proposed an East India Bill to place the government of the ailing and oppressive British East India Company, at that time in control of a considerable expanse of India, on a sounder footing with a board of governors responsible to Parliament and more resistant to Crown patronage. It passed the Commons by 153 to 80, but, when the King made it clear that any peer who voted in favour of the bill would be considered a personal enemy of the Crown, the Lords divided against Fox by 95 to 76.[22] George now felt justified in dismissing Fox and North from government, and nominating William Pitt in their place; at twenty-four years of age, the youngest Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in history was appointed to office, apparently on the authority of the votes of 19 peers. Fox used his parliamentary majority to oppose Pitt's nomination, and every subsequent measure that he put before the House, until March 1784, when the King dissolved Parliament and, in the following general election, Pitt was returned with a substantial majority.

In Fox's own constituency of Westminster the contest was particularly fierce. An energetic campaign in his favour was run by Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, allegedly a lover of Fox's who was said to have won at least one vote for him by kissing a shoemaker with a rather romantic idea of what constituted a bribe. In the end Fox was re-elected by a very slender margin, but legal challenges (encouraged, to an extent, by Pitt and the King)[23] prevented a final declaration of the result for over a year. In the meantime, Fox sat for the Scottish pocket borough of Tain or Northern Burghs, for which he was qualified by being made an unlikely burgess of Kirkwall in Orkney (which was one of the Burghs in the district). The experience of these years was crucial in Fox's political formation. His suspicions had been confirmed: it seemed to him that George III had personally scuppered both the Rockingham-Shelburne and Fox-North governments, interfered in the legislative process and now dissolved Parliament when its composition inconvenienced him. Pitt – a man of little property and no party – seemed to Fox a blatant tool of the Crown.[24] However, the King and Pitt had great popular support, and many in the press and general population saw Fox as the trouble-maker challenging the composition of the constitution and the King's remaining powers. He was often caricatured as Oliver Cromwell and Guy Fawkes during this period, as well as Satan, "Carlo Khan" (see James Sayers) and Machiavelli.[25]

1784–1788: His Majesty’s Loyal Opposition

One of Pitt’s first major actions as Prime Minister was, in 1785, to put a scheme of parliamentary reform before the Commons, proposing to rationalise somewhat the existing, decidedly unrepresentative, electoral system by eliminating thirty-six rotten boroughs and redistributing seats to represent London and the larger counties. Fox supported Pitt’s reforms, despite apparent political expediency, but they were defeated by 248 to 174.[26] Reform would not be considered seriously by Parliament for another decade.

In 1787, the most dramatic political event of the decade came to pass in the form of the Impeachment of Warren Hastings, the Governor of Bengal until 1785, on charges of corruption and extortion. Fifteen of the eighteen Managers appointed to the trial were Foxites, one of them being Fox himself.[27] Although the matter was really Burke’s area of expertise, Fox was, at first, enthusiastic. If the trial could demonstrate the misrule of British India by Hastings and the East India Company more widely, then Fox’s India Bill of 1784 – the point on which the Fox-North Coalition had been dismissed by the King – would be vindicated.[28] The trial was also expedient for Fox in that it placed Pitt in an uncomfortable political position. The premier was forced to equivocate over the Hastings trial, because to oppose Hastings would have been to endanger the support of the king and the East India Company, while to openly support him would have alienated country gentlemen and principled supporters like Wilberforce.[29] However, as the trial's intricacies dragged on (it would be 1795 before Hastings was finally acquitted), Fox's interest waned and the burden of managing the trial devolved increasingly on Burke.

Fox was also reputed to be the anonymous author of An Essay Upon Wind; with Curious Anecdotes of Eminent Peteurs. Humbly Dedicated to the Lord Chancellor in 1787.

1788–1789: The Regency Crisis

In late October 1788, George III descended into a bout of insanity, probably caused by an attack of the hereditary disease porphyria. He had declared that Pitt was "a rascal" and Fox "his Friend".[30] The King was placed under restraint and a rumour went round that Fox had poisoned him.[30] Thus the opportunity revealed itself for the establishment of a regency under Fox’s friend and ally, the Prince of Wales, which would take the reins of government out of the hands of the incapacitated George III and allow the replacement of his 'minion', Pitt, with a Foxite ministry.

Fox, however, was out of contact in Italy as the crisis broke; he had resolved not to read any newspapers while he was abroad, except the racing reports.[31] Three weeks passed before he returned to Britain on 25 November 1788 and then he was taken seriously ill (partly due to the stress of his rapid journey across Europe) and would not recover entirely until December 1789. He again absented himself to Bath from 27 January to 21 February 1789.[32] When Fox did make it into Parliament, he seemed to make a serious political error. In the Commons on 10 December, he declared that it was the right of the Prince of Wales to install himself as regent immediately. It is said that Pitt, upon hearing this, slapped his thigh in an uncharacteristic display of emotion and declared that he would "unwhig" Fox for the rest of his life. Fox's argument did indeed seem to contradict his life-long championing of Parliament's rights over the Crown. Pitt pointed out that the Prince of Wales had no more right to the throne than any other Briton, though he may well have – as the King's firstborn – a better claim to it. It was Parliament’s constitutional right to decide. However, there was more than naked thirst for power in Fox's seemingly hypocritical Tory assertion. Fox believed that the King's illness was permanent, and therefore that George III was, constitutionally speaking, dead. To challenge the Prince of Wales's right to succeed him would be to challenge fundamental contemporary assumptions about property rights and primogeniture. Pitt, on the other hand, considered the King's madness temporary (or, at least, hoped that it would be), and thus saw the throne as temporarily unoccupied rather than vacant.[33]

While Fox drew up lists for his proposed Cabinet under the new Prince Regent, Pitt spun out the legalistic debates over the constitutionality of and precedents for instituting a regency, as well as the actual process of drawing up a Regency Bill and navigating it through Parliament. He negotiated a number of restrictions on the powers of the Prince of Wales as regent (which would later provide the basis of the Regency of 1811), but the bill finally passed the Commons on 12 February. As the Lords too prepared to pass it, they learned that the King’s health was improving and decided to postpone further action. The King soon regained lucidity in time to prevent the establishment of his son’s regency and the elevation of Fox to the prime ministership, and, on 23 April, a service of thanksgiving was conducted at St Paul’s in honour of George III’s return to health.[34] Fox’s opportunity had passed.

1789–1791: The French Revolution

Fox welcomed the French Revolution of 1789, interpreting it as a late Continental imitation of Britain's Glorious Revolution of 1688. In response to the Storming of the Bastille on 14 July, he famously declared, "How much the greatest event it is that ever happened in the world! and how much the best!"[4] In April 1791, Fox told the Commons that he "admired the new constitution of France, considered altogether, as the most stupendous and glorious edifice of liberty, which had been erected on the foundation of human integrity in any time or country."[35] He was thus somewhat bemused by the reaction of his old Whig friend, Edmund Burke, to the dramatic events across the Channel. In his Reflections on the Revolution in France, Burke warned that the revolution was a violent rebellion against tradition and proper authority, motivated by utopian, abstract ideas disconnected from reality, which would lead to anarchy and eventual dictatorship. Fox read the book and found it "in very bad taste" and "favouring Tory principles",[36] but avoided pressing the matter for a while to preserve his relationship with Burke. The more radical Whigs, like Sheridan, broke with Burke more readily at this point.

Fox instead turned his attention – despite the politically volatile situation – to repealing the Test and Corporation Acts, which restricted the liberties of English Dissenters and Catholics. On 2 March 1790, Fox gave a long and eloquent speech to a packed House of Commons.

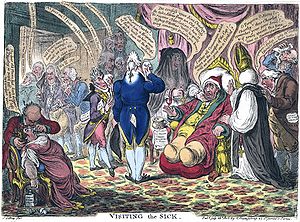

A Birmingham toast, as given on the 14th July: Fox is caricatured by Gillray as toasting the anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille with Joseph Priestley and other Dissenters (23 July 1791)

A Birmingham toast, as given on the 14th July: Fox is caricatured by Gillray as toasting the anniversary of the Storming of the Bastille with Joseph Priestley and other Dissenters (23 July 1791) Persecution always says, 'I know the consequences of your opinion better than you know them yourselves.' But the language of toleration was always amicable, liberal, and just: it confessed its doubts, and acknowledged its ignorance ... Persecution had always reasoned from cause to effect, from opinion to action, [that such an opinion would invariably lead to but one action], which proved generally erroneous; while toleration led us invariably to form just conclusions, by judging from actions and not from opinions.[37]

Persecution always says, 'I know the consequences of your opinion better than you know them yourselves.' But the language of toleration was always amicable, liberal, and just: it confessed its doubts, and acknowledged its ignorance ... Persecution had always reasoned from cause to effect, from opinion to action, [that such an opinion would invariably lead to but one action], which proved generally erroneous; while toleration led us invariably to form just conclusions, by judging from actions and not from opinions.[37]Pitt, in turn, came to the defence of the Acts as adopted

by the wisdom of our ancestors to serve as a bulwark to the Church, whose constituency was so intimately connected with that of the state, that the safety of the one was always liable to be affected by any danger which might threaten the other.[37]Burke, with fear of the radical upheaval in France foremost in his mind, took Pitt's side in the debate, dismissing Nonconformists as "men of factious and dangerous principles", to which Fox replied that Burke's "strange dereliction from his former principles ... filled him with grief and shame". Fox's motion was defeated in the Commons by 294 votes to 105.[38] Later, Fox successfully supported the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791, extending the rights of British Catholics. He explained his stance to his Catholic friend Charles Butler, declaring:

the best ground, and the only ground to be defended in all points is, that action, not principle is the object of law and legislation; with a person's principles no government has any right to interfere.[39]On the world stage of 1791, war threatened more with Spain and Russia than revolutionary France. Fox opposed the bellicose stances of Pitt's ministry in the Nootka Sound crisis, and over the Russian occupation of the Turkish port of Ochakiv on the Black Sea. Fox contributed to the peaceful resolution of these entanglements, and gained a new admirer in Catherine the Great, who bought a bust of Fox and placed it between Cicero and Demosthenes in her collection.[4] On 18 April, Fox spoke in the Commons – together with William Wilberforce, Pitt and Burke – in favour of a measure to abolish the slave trade, but – despite their combined rhetorical talents – the vote went against them by a majority of 75.[40]

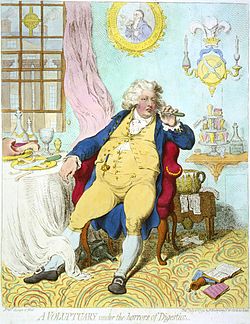

In The Hopes of the Party (1791), Gillray caricatured Fox with an axe about to strike off the head of George III, in imitation of the French Revolution.

In The Hopes of the Party (1791), Gillray caricatured Fox with an axe about to strike off the head of George III, in imitation of the French Revolution.

On 6 May 1791, a tearful confrontation on the floor of the Commons (officially, and rather irrelevantly, during a debate on the particulars of a bill for the government of Canada) finally shattered the quarter-century friendship of Fox and Burke, as the latter dramatically crossed the floor of the House to sit down next to Pitt, taking the support of a good deal of the more conservative Whigs with him.[41] Later, on his deathbed in 1797, Burke would have his wife turn Fox away rather than allow a final reconciliation.

1791–1797: "Pitt's Terror"

Fox continued to defend the French Revolution, even as its fruits began to collapse into war, repression and the Reign of Terror. Though there were few developments in France after 1792 that Fox could positively favour[42] (the guillotine claimed the life of his old friend, the duc de Biron, among many others) Fox maintained that the old monarchical system still proved a greater threat to liberty than the new, degenerating experiment in France. Fox thought of revolutionary France as the lesser of two evils, and emphasised the role of traditional despots in perverting the course of the revolution: he argued that Louis XVI and the French aristocracy had brought their fates upon themselves by abusing the constitution of 1791 and that the coalition of European autocrats, which was currently dispatching its armies against France's borders, had driven the revolutionary government to desperate and bloody measures by exciting a profound national crisis. Fox was not surprised when Pitt and the King brought Britain into the war as well, and would afterwards blame the pair and their prodigal European subsidies for the long-drawn-out continuation of the French Revolutionary Wars. In 1795, he wrote to his nephew, Lord Holland:

Peace is the wish of the French of Italy Spain Germany and all the world, and Great Britain alone the cause of preventing its accomplishment, and this not for any point of honour or even interest, but merely lest there should be an example in the modern world of a great powerful Republic.[43]Rather ironically, while Fox was being denounced by many in Britain as a Jacobin traitor, across the Channel he featured on a 1798 list of the Britons to be transported after a successful French invasion of Britain. According to the document, Fox was a "false patriot; having often insulted the French nation in his speeches, and particularly in 1786."[44] According to one of his biographers, Fox's "loyalties were not national but were offered to people like himself at home or abroad".[4] In 1805 Francis Horner wrote that: "I could name to you gentlemen, with good coats on, and good sense in their own affairs, who believe that Fox...is actually in the pay of France".[45]

But Fox's radical position soon became too extreme for many of his followers, particularly old Whig friends like the Duke of Portland, Earl Fitzwilliam and the Earl of Carlisle. Around July 1794 their fear of France outgrew their resentment towards Pitt for his actions in 1784, and they crossed the floor to the Government benches. Fox could not believe that they "would disgrace" themselves in such a way.[4] After these defections, the Foxites could no longer constitute a credible parliamentary opposition, reduced, as they were, to some fifty MPs.[46]

Fox, however, still insisted on challenging the repressive wartime legislation introduced by Pitt in the 1790s that would become known (rather exaggeratedly) as "Pitt's Terror". In 1792, Fox had seen through the only piece of substantial legislation in his career, the Libel Act 1792, which restored to juries the right to decide what was and was not libellous, in addition to whether a defendant was guilty. E.P. Thompson thought it "Fox's greatest service to the common people, passed at the eleventh hour before the tide turned toward repression."[47] Indeed, the act was passed by Parliament on 21 May, the same day as a royal proclamation against seditious writings was issued, and more libel cases would be brought by the government in the following two years than had been in all the preceding years of the eighteenth century.[2]

Fox spoke in opposition to the King's Speech on 13 December 1793, but was defeated in the subsequent division by 290 to 50.[48] He argued against war measures like the stationing of Hessian troops in Britain, the employment of royalist French émigrés in the British army and, most of all, Pitt's suspension of habeas corpus in 1794. He told the Commons that:

In 1795, the King's carriage was assaulted in the street, providing an excuse for Pitt to introduce the infamous Two Acts: the Seditious Meetings Act 1795, which prohibited unlicensed gatherings of over fifty people, and the Treasonable Practices Act, which greatly widened the legal definition of treason, making any assault on the constitution punishable by seven years' transportation. Fox spoke ten times in the debate on the acts.[50] He argued that, according to the principles of the proposed legislation, Pitt should have been transported a decade before in 1785, when he had being advocating parliamentary reform.[51] Fox warned the Commons that

"if you silence remonstrance and stifle complaint, you then leave no other alternative but force and violence. "[50]He argued that "the best security for the due maintenance of the constitution was in the strict and incessant vigilance of the people over parliament itself. Meetings of the people, therefore, for the discussion of public objects were not merely legal, but laudable."[2]

Parliament passed the acts. But Fox enjoyed a swell of extra-parliamentary support during the course of the controversy. A substantial petitioning movement arose in support of him, and on 16 November 1795, he addressed a public meeting of between two- and thirty-thousand people on the subject.[50] However, this came to nothing in the long run. The Foxites were becoming disenchanted with the Commons, overwhelmingly dominated by Pitt, and began to denounce it to one another as unrepresentative.[52]

1797–1806: Political wilderness

By May 1797, an overwhelming majority – both in and outside of Parliament – had formed in support of Pitt's war against France. Fox's following in Parliament had shrivelled to about 25, compared with around 55 in 1794 and at least 90 during the 1780s. Many of the Foxites purposefully seceded from Parliament in 1797; Fox himself retired for lengthy periods to his wife's house in Surrey.[52] The distance from the stress and noise of Westminster was an enormous psychological and spiritual relief to Fox,[53] but still he defended his earlier principles: "It is a great comfort to me to reflect how steadily I have opposed this war, for the miseries it seems likely to produce are without end."[2]

In May 1798 Fox proposed a toast to "Our Sovereign, the Majesty of the People". The Duke of Norfolk had made the same toast in January at Fox's birthday dinner and had been dismissed as Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding as a result. Pitt thought of sending Fox to the Tower of London for the duration of the parliamentary session but instead removed him from the Privy Council.[54] Fox believed that it was "impossible to support the Revolution [of 1688] and the Brunswick Succession upon any other principle" than the sovereignty of the people.[55]

After the Peace of Amiens (which he welcomed wholeheartedly) Fox joined the thousands of English tourists flocking across the Channel to see the sights of the revolution. Fox and his retinue were kept under surveillance by officials from the British embassy during their trip of 20 July to 17 November.[4] In Paris, he presented his wife, Elizabeth Armistead, for the first time in seven years of marriage, creating yet another stir back at court in London, and had three interviews with Napoleon, who – though he tried to flatter his most prominent British sympathiser – had to spend most of the time arguing about the freedom of the press and the perniciousness of a standing army.[4] Fox thought the coup d'état that brought Napoleon to power "a very bad beginning ... the manner of the thing [was] quite odious",[56] but he was convinced that the French leader sincerely desired peace in order to consolidate his rule and rebuild his shattered country. Upon hearing of the spectacular French victories at Ulm and Austerlitz later in 1805, Fox commented

1806: Final year

After Pitt’s resignation in February 1801, Fox had undertaken a partial return to politics. Having opposed the Addington ministry (though he approved of its negotiation of the Peace of Amiens) as a Pitt-style tool of the King, Fox gravitated towards the Grenvillite faction, which shared his support for Catholic emancipation and composed the only parliamentary alternative to a coalition with the Pittites. Thus, when Pitt (who had replaced Addington in 1804 to become Prime Minister once more) died on 23 January 1806, Fox was the last remaining great political figure of the era, and could no longer be denied a place in government.[2] When Grenville formed a "Ministry of All the Talents" out of his supporters, the followers of Addington and the Foxites, Fox was once again offered the post of Foreign Secretary, which he accepted. Though the administration failed to achieve either Catholic emancipation or peace with France, Fox’s last great achievement would be the abolition of the slave trade in 1807. Though Fox would die before abolition was formalised, he oversaw a Foreign Slave Trade Bill in spring 1806 that prohibited British subjects from contributing to the trading of slaves with the colonies of Britain’s wartime enemies, thus eliminating two-thirds of the slave trade passing through British ports.

On 10 June 1806, Fox offered a resolution for total abolition to Parliament: "this House, conceiving the African slave trade to be contrary to the principles of justice, humanity, and sound policy, will, with all practicable expedition, proceed to take effectual measures for abolishing the said trade..." The House of Commons voted 114 to 15 in favour and the Lords approved the motion on 25 June.[2] Fox said that:

So fully am I impressed with the vast importance and necessity of attaining what will be the object of my motion this night, that if, during the almost forty years that I have had the honour of a seat in parliament, I had been so fortunate as to accomplish that, and that only, I should think I had done enough, and could retire from public life with comfort, and the conscious satisfaction, that I had done my duty.[4]Death

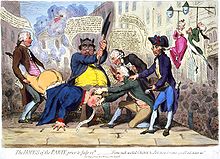

In Comforts of a Bed of Roses (1806), Gillray depicts Death crawling out from under Fox's covers, entwined with a scroll inscribed "Intemperance, Dropsy, Dissolution".

In Comforts of a Bed of Roses (1806), Gillray depicts Death crawling out from under Fox's covers, entwined with a scroll inscribed "Intemperance, Dropsy, Dissolution".

Fox died – still in office – at Chiswick House, west of London, in 1806, not eight months after the younger Pitt. An autopsy revealed a hardened liver, thirty-five gallstones, and around seven pints of transparent fluid in his abdomen.[4] Fox also left £10,000-worth of debts,[58] though this was only a quarter of the £40,000 that the charitable public had to raise to pay off Pitt's arrears.[4] Although Fox had wanted to be buried near his home in Chertsey, his funeral took place in Westminster Abbey on 10 October 1806, the anniversary of his initial election for Westminster in 1780. Unlike Pitt's, Fox's funeral was a private affair, but still the crowds who turned out to pay their respects were at least as large as those at his rival's service.[4]

Private life

Fox's private life (as far as it was private) was notorious, even in an age noted for the licentiousness of its upper classes. Fox was famed for his rakishness and his drinking; vices which were both indulged frequently and immoderately. Fox was also an infamous gambler, once claiming that winning was the greatest pleasure in the world, and losing the second greatest. Between 1772 and 1774, Fox's father had – shortly before dying – had to pay off £120,000 of Charles' debts; the equivalent of around £11 million at today's prices. Fox was twice bankrupted between 1781 and 1784,[4] and at one point his creditors confiscated his furniture.[2] Fox's finances were often "more the subject of conversation than any other topic."[59] By the end of his life, Fox had lost about £200,000 gambling.[60]

In appearance, Fox was dark, corpulent and hairy, to the extent that when he was born his father compared him to a monkey.[4] His round face was dominated by his luxuriant eyebrows, with the result that he was known among the Whigs as 'the Eyebrow.' Though he became increasingly dishevelled and fat in middle age, the young Fox had been a very fashionable figure; in particular, he had been the leader of the 'Maccaroni' set of extravagant young followers of Continental fashions. Fox enjoyed riding and cricket but, in the latter case, the combination of his impulsive nature and considerable weight led to his often being run out between wickets.[4]

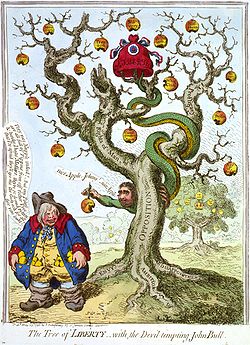

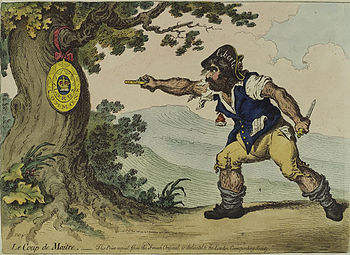

Le Coup de Maitre. – This Print copied from the French Original, is dedicated to the London Corresponding Society (1797): a caricature of Fox by Gillray, showing the Whig as a sans-culottes taking aim at the constitutional target of Crown, Lords and Commons.

Le Coup de Maitre. – This Print copied from the French Original, is dedicated to the London Corresponding Society (1797): a caricature of Fox by Gillray, showing the Whig as a sans-culottes taking aim at the constitutional target of Crown, Lords and Commons.

Fox was also probably the most ridiculed figure of the 18th century – most famously by Gillray, for whom he served as a stock Jacobin villain. The King regarded Fox as beyond morality and the corrupter of his own eldest son, and the swelling late eighteenth-century movements of Christian evangelism and middle-class 'respectability' also frowned on his excesses. However, Fox was apparently not greatly bothered by these criticisms, and indeed kept a collection of his caricatures.[4] His friend, Frederick Howard, 5th Earl of Carlisle, said of him that, since "the respect of the world was not easily retrievable, he became so callous to what was said of him, as never to repress a single thought, or even temper a single expression when he was before the public."[61] Indeed, particularly after 1794, Fox could be considered at fault for rarely consulting the opinions of anyone outside of his own circle of friends and supporters.[4]

Fox was also regarded as a notorious womaniser in a period when a mistress was a practical necessity for a London gentleman. In 1784 or 1785, Fox met and fell in love with Elizabeth Armistead, a former courtesan and mistress of the Prince of Wales who had little interest in politics or Parliament.[62] He married her in a private ceremony at Wyton in Huntingdonshire on 28 September 1795, but did not make the fact public until October 1802, and Elizabeth was never really accepted at court. Fox would increasingly spend time away from Parliament at Armistead's rural villa, St. Ann's Hill, near Chertsey in Surrey, where Armistead's influence gradually moderated Fox's wilder behaviour and together they would read, garden, explore the countryside and entertain friends. In his last days, the sceptical Fox allowed scriptural readings at his bedside in order to please his religious wife. She would survive him by some thirty-six years, dying on 8 July 1842, at the age of ninety-one.[4]

Despite his celebrated flaws, history records Fox as an amiable figure. The Tory wit George Selwyn wrote that, "I have passed two evenings with him, and never was anybody so agreeable, and the more so from his having no pretensions to it". Selwyn also said that "Charles, I am persuaded, would have no consideration on earth but for what was useful to his own ends. You have heard me say, that I thought he had no malice or rancour; I think so still and am sure of it. But I think that he has no feeling neither, for anyone but himself; and if I could trace in any one action of his life anything that had not for its object his own gratification, I should with pleasure receive the intelligence because then I had much rather (if it were possible) think well of him than not".[63] Sir Philip Francis said of Fox: "The essential defect in his character and the cause of all his failures, strange as it may seem, was that he had no heart".[63] Edward Gibbon remarked that "Perhaps no human being was ever more perfectly exempt from the taint of malevolence, vanity, or falsehood."[2] Central to understanding Fox's life was his view that "friendship was the only real happiness in the world."[64] For Fox, politics was the extension of his activities at Newmarket and Brooks's to Westminster.[4] "Fox had little or no interest in the exercise of power."[1] The details of policy – particularly of economics – bored him, in contrast with the intensity of Burke’s legal pursuit of Warren Hastings, and of Pitt’s prosecution of the war against France. Moreover, the Foxites were "the witty and wicked" satellites of their leader, as much friends as political allies.[65] Indeed, Fox's generous nature (helped by his earlier over-indulgence by his father) made him a rather hopeless political party-leader, often seeming quite unwilling to cajole or discipline his unruly supporters, especially in the case of the young, who were disproportionately represented among the Foxites. Perhaps one great testament to Fox's character is that subscriptions to the old Whig club of Brooks's would decline on the rare occasions when he was called away to government office, because one of the prime entertainments would no longer be available.[4]

Legacy

In the 19th century, liberals portrayed Fox as their hero, praising his courage, perseverance and eloquence. They celebrated his opposition to war in alliance with European despots against the people of France eager for their freedom, and they praised his fight for liberties at home. The liberals saluted his rights for parliamentary reform, Catholic Emancipation, intellectual freedom, and justice for the Dissenters. They were especially pleased with his fight for the abolition of the slave trade. More recent historians put Fox in the context of the 18th century, and emphasized the brilliance of his battles with Pitt.[66]

While not wholly forgotten today Fox is no longer the famous hero he had been, and is less well remembered than Pitt.[4] Strikingly, particularly after 1794, the word 'Whig' gave way to the word 'Foxite' as the self-description of the members of the opposition to Pitt. In many ways, the Pittite-Foxite division of Parliament after the French Revolution established the basis for the ideological Conservative-Liberal divide of the nineteenth century. Fox and Pitt went down in parliamentary history as legendary political and oratorical opponents who would not be equalled until the days of Gladstone and Disraeli more than half a century later. Even Fox’s great rival was willing to acknowledge the old Whig’s talents. When, in 1790, the comte de Mirabeau disparaged Fox in Pitt's presence, Pitt stopped him, saying, "You have never seen the wizard within the magic circle."[67]

As Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey asked a Newcastle-upon-Tyne Fox dinner in 1819: "What subject is there, whether of foreign or domestic interest, or that in the smallest degree affects our Constitution which does not immediately associate itself with the memory of Mr Fox?"[4] Fox's name was invoked numerous times in debates by supporters of Catholic Emancipation and the Great Reform Act in the early nineteenth century. John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford kept a bust of Fox in his pantheon of Whig grandees at Woburn Abbey and erected a statue of him in Bloomsbury Square. Sarah Siddons kept a portrait of Fox in her dressing room. In 1811, the Prince of Wales took the oaths of office as regent with a bust of Fox at his side. Whig households would collect locks of Fox's hair, books of his conflated speeches and busts in his likeness. The Fox Club was established in London in 1790 and held the first of its Fox dinners – annual events celebrating Fox's birthday – in 1808; the last recorded dinner taking place at Brooks's in 1907.[4] Following on from this the Fox Poker Club opened its doors on 24 September 2010 on Shaftesbury Avenue, London's first and only fully licensed poker club.

"Charles James" or simply "Charlie" is to the present day a common nickname applied by practitioners of the sport to the quarry pursued by packs of foxhounds.

Memorial to Fox erected by William Chamberlayne on his estate at Weston, now within Mayfield Park, Southampton.

Memorial to Fox erected by William Chamberlayne on his estate at Weston, now within Mayfield Park, Southampton.

In addition, the town of Foxborough in Massachusetts was named in honour of the staunch supporter of American independence. Fox is remembered in his home town of Chertsey by a bust on a high plinth (pictured right), erected in 2006 in a new development by the railway station. Fox is also commemorated in a termly dinner held in his honour at his alma mater, Hertford College, Oxford, by students of English, history and the romance languages.

Fox featured as a character in the 1994 movie The Madness of King George, portrayed by Jim Carter; in the 2006 movie Amazing Grace, played by Michael Gambon; and in the 2008 movie The Duchess, played by Simon McBurney. Fox is also portrayed in the 1999 BBC mini series Aristocrats.

In September 2010 the 'Fox Poker Club' named after Charles James Fox, was opened in London's Shaftesbury Avenue. A portrait of the rotund figure hangs proudly in the club's foyer.

Ancestry

Charles James Fox's ancestors in three generations Charles James Fox

Father

Henry Fox, 1st Baron HollandFather's father

Sir Stephen FoxFather's father's father

William FoxFather's father's mother

Elizabeth PaveyFather's mother

Christiana HopeFather's mother's father

Rev. Francis HopeFather's mother's mother

Christian PalfreymanMother

Lady Caroline LennoxMother's father

Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of RichmondMother's father's father

Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Richmond and LennoxMother's father's mother

Anne BrudenellMother's mother

Lady Sarah CadoganMother's mother's father

William Cadogan, 1st Earl CadoganMother's mother's mother

Margaret Cecilia MunterNotes

- ^ a b Mitchell 1992, p. 264

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Powell 1996

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 7–8

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah Mitchell 2007

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 4

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 10

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 16

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 8

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 26

- ^ Rudé 1962, p. 162

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 27

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 62

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 63

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 108

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 109

- ^ Thompson 1963, p. 78

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 137

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 169

- ^ Pares 1953, p. 120

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 171

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 88

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 190

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 206

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 75

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 73

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 214

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 76

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 77

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 78

- ^ a b Mitchell 1992, p. 80

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 232

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 81

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 82

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 245

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 266

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 113

- ^ a b Reid 1969, p. 261

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 262

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 260

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 267

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 269

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 124

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 162

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 159

- ^ Horner 1843, p. 323

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 136

- ^ Thompson 1963, p. 135

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 132

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 133

- ^ a b c Mitchell 1992, p. 140

- ^ Watson 1960, p. 360

- ^ a b Mitchell 1992, p. 141

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 146

- ^ Emsley 1979, p. 67

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 152

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 166

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 218

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 106

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 101

- ^ Olmert 1996, p. 98

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 14

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 179

- ^ a b Christie 1970, p. 143

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 12

- ^ Mitchell 1992, p. 265

- ^ Greaves 1973, p. 687–88

- ^ Reid 1969, p. 268

Bibliography

- Derry, John W. (1972). Charles James Fox. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Mitchell, Leslie (1992). Charles James Fox.

- Mitchell, Leslie (2004). "Fox, Charles James (1749–1806)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/10024. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- Pares, Richard (1953). King George III and the Politicians. http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=7861542.

- Powell, Jim (September 1996). "Charles James Fox, Valiant Voice for Liberty". The Freeman: Ideas on Liberty 46 (9). http://www.fee.org/publications/the-freeman/article.asp?aid=4347.

- Reid, Loren (1969). Charles James Fox: A Man for the People.

- Rudé, George (1962). Wilkes & Liberty.

- Thompson, E.P. (1963). The Making of the English Working Class.

- Trevelyan, George Otto (1912). George the Third and Charles Fox: The Concluding Part of the American Revolution. 1. http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=6035149.

- Trevelyan, George Otto (1912). George the Third and Charles Fox: The Concluding Part of the American Revolution. 2. http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=65473061.

- Trevelyan, George Otto (1880). The Early History of Charles James Fox. http://books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC23113172&id=rJcgAAAAMAAJ&printsec=toc&dq=%22charles+james+fox%22&sig=qexOuKt8dt4wlYJ3c5OL9avKf24.

- Watson, J. Steven (1960). The Reign of George III, 1760–1815. http://www.questia.com/PM.qst?a=o&d=22810171.

- Leslie Mitchell (2007). Charles James Fox. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- Horner, Leonard (1843). Memoirs and Correspondence of Francis Horner, M.P.. 1. London: John Murray.

- Emsley (1979). British Society and the French Wars, 1793–1815. Macmillan.

- Olmert, Michael (1996). Milton's Teeth and Ovid's Umbrella: Curiouser & Curiouser Adventures in History. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0684801647.

- Christie, I. R. (1970). Myth and Reality in Late-Eighteenth-Century British Politics and Other Papers. Macamillan.

- Greaves, R. W. (June 1973). "Reviews of Books". American Historical Review 78 (3).

Primary sources

- Fox, Charles James (1853). The Speeches of the Right Honourable Charles James Fox in the House of Commons. http://books.google.com/books?vid=OCLC12546677&id=4EEJiAHWgk8C&printsec=toc&dq=%22charles+james+fox%22&sig=_FA0tp0o4IO7in3jHt_GuqGajZY.

External links

- Works by Charles James Fox at Project Gutenberg

- History of the Early Part of the Reign of James the Second at Project Gutenberg

- Guardian article on Fox as the 200th anniversary of his death approaches

- BBC article

Parliament of Great Britain Preceded by

Bamber Gascoyne

John BurgoyneMember of Parliament for Midhurst

1768 – 1774

With: Lord StavordaleSucceeded by

Herbert Mackworth

Clement TudwayPreceded by

Lord Thomas Pelham-Clinton

Viscount MaldenMember of Parliament for Westminster

1780 – 1801

With: Sir George Rodney, Bt 1780–1782

Sir Cecil Wray, Bt 1782–1784

Samuel Hood 1784–1788, 1790–1796

Lord John Townshend 1788–1790

Sir Alan Gardner, Bt 1796–1801Succeeded by

Parliament of the United KingdomPreceded by

Charles RossMember of Parliament for Tain Burghs

1784–1786Succeeded by

George RossParliament of the United Kingdom Preceded by

Parliament of Great BritainMember of Parliament for Westminster

1801–1806

With: Sir Alan Gardner, BtSucceeded by

Sir Alan Gardner, Bt

Earl PercyPolitical offices Preceded by

New OfficeForeign Secretary

1782Succeeded by

The Lord GranthamPreceded by

Lord NorthLeader of the House of Commons

1782Succeeded by

Thomas TownshendPreceded by

The Lord GranthamForeign Secretary

1783Succeeded by

The Earl TemplePreceded by

Thomas TownshendLeader of the House of Commons

1783

With: Lord NorthSucceeded by

William PittPreceded by

The Lord MulgraveForeign Secretary

1806Succeeded by

Viscount HowickPreceded by

William PittLeader of the House of Commons

1806Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Fox · Grantham · Fox · Temple · Leeds · Grenville · Hawkesbury · Harrowby · Mulgrave · Fox · Howick · Canning · Bathurst · Wellesley · Castlereagh · Canning · Dudley · Aberdeen · Palmerston · Wellington · Palmerston · Aberdeen · Palmerston · Granville · Malmesbury · Russell · Clarendon · Malmesbury · Russell · Clarendon · Stanley · Clarendon · Granville · Derby · Salisbury · Granville · Salisbury · Rosebery · Iddesleigh · Salisbury · Rosebery · Kimberley · Salisbury · Lansdowne · Grey · Balfour · Curzon · MacDonald · Chamberlain · Henderson · Reading · Simon · Hoare · Eden · Halifax · Eden · Bevin · Morrison · Eden · Macmillan · Lloyd · Home · Butler · Gordon Walker · Stewart · Brown · Stewart

Secretary of State for Foreign

and Commonwealth Affairs Book:Secretaries of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs ·

Book:Secretaries of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs ·  Category:British Secretaries of State ·

Category:British Secretaries of State ·  Portal:United KingdomCategories:

Portal:United KingdomCategories:- 1749 births

- 1806 deaths

- Alumni of Hertford College, Oxford

- British MPs 1768–1774

- British MPs 1780–1784

- British MPs 1784–1790

- British MPs 1790–1796

- British MPs 1796–1800

- British Secretaries of State for Foreign Affairs

- Burials at Westminster Abbey

- Duellists

- English abolitionists

- Lords of the Admiralty

- Members of the Privy Council of Great Britain

- Members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom

- Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for English constituencies

- Members of the Parliament of Great Britain for Scottish constituencies

- Members of the United Kingdom Parliament for English constituencies

- Old Etonians

- UK MPs 1801–1802

- UK MPs 1802–1806

- Younger sons of barons

- Leaders of the House of Commons

- Fox family (English aristocracy)

Wikimedia Foundation. 2010.