- Chiswick House

-

Chiswick House

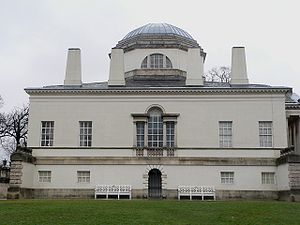

General information Type Historic house Architectural style Neo-Palladian villa Address Burlington Lane Town or city London Borough of Hounslow, Greater London Country England Coordinates 51°29′1″N 0°15′31″W / 51.48361°N 0.25861°W Groundbreaking 1726 Completed 1729 Design and construction Architect Lord Burlington, William Kent Website www.english-heritage.org.uk Chiswick House is a Palladian villa in Burlington Lane, Chiswick, in the London Borough of Hounslow in England. Set in 65 acres (0.26 km2), the house was completed in 1729 during the reign of George II and designed by Lord Burlington. William Kent (1685–1748), who took a leading role in designing the gardens, created one of the earliest examples of the English landscape garden on the property. The villa is arguably the finest remaining example of Neo-Palladian architecture in London.

After the death of its builder and original occupant in 1753, and the subsequent deaths of his last surviving daughter Charlotte Boyle in 1754 and his widow in 1758, the property was ceded to the Cavendish family and William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, the husband of Charlotte. After William's death in 1764, the villa passed to his and Charlotte's orphaned young son, William, the 5th Duke of Devonshire. Although it was not used as his main residence, his wife Georgiana Spencer, a prominent but controversial figure in fashion and politics whom he married in 1774, used the house as a retreat and as a Whig stronghold for many years, being the place of death of Charles James Fox in 1806. Tory Prime Minister George Canning also died there, in 1827.

During the 19th century it fell into decline, but evaded being demolished, and was rented out by the Cavendish family, and used as a hospital from 1892. In 1929, the 9th Duke of Devonshire finally sold Chiswick House to Middlesex County Council and it became a firestation. The villa suffered damage during World War II, and in 1944 a V2 rocket damaged one of the two wings. The wings were demolished in 1956. Today the house is a Grade 1 listed building, and is maintained by English Heritage.

Contents

History

Origins

Chiswick House was inherited by Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington, 4th Earl of Cork and Baron Clifford (1694–1753) on the death of his father, Charles Boyle, in 1704.[1] The mansion was a medium-sized Jacobean house used as a summer retreat from the heat of London, where the family resided at Burlington House, today the Royal Academy).[1][2] After a fire in the old Jacobean house in 1725, Burlington decided to build a new 'Villa' to the west of Chiswick House. During his trip to Italy in 1719 the Earl had acquired a passion for Palladian architecture.[3][4] Burlington had never closely inspected Roman ruins or made detailed drawings on the sites in Italy; he relied on Palladio and Scamozzi as his interpreters of the classic tradition.[5] Another source of his inspiration were drawings he collected, including those of Palladio himself, which had belonged to Inigo Jones and his pupil John Webb. According to Howard Colvin, "Burlington's mission was to reinstate in Augustan England the canons of Roman architecture as described by Vitruvius, exemplified by its surviving remains, and practised by Palladio, Scamozzi and Jones."[6]

Burlington, himself a talented amateur architect and (in the words of Horace Walpole) "Apollo of the Arts",[7] designed the villa with the aid of William Kent (1685–1748), who took a leading role in designing the gardens. It became one of the earliest examples of the English landscape garden, a movement with which Kent became closely associated.[8] Burlington built the villa with enough room to house his prized art collection, regarded as containing "some of the best pictures in Europe",[9] and his extensive array of furniture, much of which was purchased on his first Grand Tour of Europe in 1714. Construction of the villa took place between 1726 and 1729.[10]

Chiswick House has also been linked with Freemasonry,[11] and is believed by some scholars to have functioned as a Masonic Lodge or Temple, given that some of the ceiling paintings by William Kent in the Gallery and the Red, Blue and Summer Parlour Rooms contain iconography of a strong Masonic, Hermetic, and possible Jacobite character.[11][12] Lord Burlington's status as an important Freemason is indicated by his inclusion in the Freemason's Pocket Companion of 1736 and in a poem in James Anderson's Constitutions of the Free Masons of 1723 where he is linked to an illustrious line of personalities. Pat Rogers has argued that Chiswick House was a symbolic temple, based on so-called Royal Arch Freemasonry, involving a Hermetic intervention designed to heal the sufferings of the exiled Jews.[11]

After completion of the villa in 1729, Burlington later provided inspiration to other architects for numerous other buildings, such as Thomas Coke, 1st Earl of Leicester at Holkham Hall, Norfolk[13] Charles Lennox, 2nd Duke of Richmond, at Goodwood House, and the Mansion House, nicknamed the "Egyptian Hall" for its columns.[14] Both Coke and Lennox were prominent Freemasons and adopted Masonic characteristics and themes on their properties.

The musician and musical historian Jane Clark, in her 1995 paper Lord Burlington is Here,[15] claimed that Lord Burlington led a secret double life as a Whig aristocrat and loyal supporter of the newly installed Hanoverian regime, and as a Jacobite supporter who was secretly facilitating the return of the exiled Stuart monarchy.[16] After the completion of the Villa Burlington fell into debt, and was forced into selling his Irish estates. Clark argues that the Earl's impecunity was caused by his loaning of money to the exiled Stuart Court.[15] This view has been supported by the historian Edward Corp, who has concluded, "there is now enough evidence available to suggest that Lord Burlington can no longer be regarded as the embodiment of a Whig ideal. Too many circumstances point to his having had Jacobite connections, directly when travelling on the Continent, through his freemasonry,through his cousin Charles Boyle, 4th Earl of Orrery, through Bishop Atterbury, through Dr Drake (the Jacobite historian of York), and via servants such as his chaplain Aaron Thompson or his agent Andrew Crotty".[17] For Clark then, the true purpose of Chiswick Villa was as a symbolic Royal Palace which awaited the return of the 'Kings over the water' who were destined to rule by ‘Divine Right’, an intepretation supported by architectural historian Giles Worsley and others.

Succession

Burlington died on 15 December 1753.[18] His wife, Lady Dorothy Savile, and daughter, Charlotte, inherited the house. Charlotte had married William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire in 1748.[19] Charlotte died in December 1754[20] and Lady Burlington died in September 1758,[16] so the villa and gardens passed to the Cavendish family, as did numerous other Boyle residences including Bolton Abbey,[21] Londesborough Hall in the East Riding of Yorkshire,[22] and Lismore Castle in Ireland.[23] William Cavendish died in 1764, leaving the property to his son William, the 5th Duke of Devonshire.

The Georgiana period

On 5 June 1774, William married Lady Georgiana Spencer (1757–1806),[24] a colourful character who became something of a national female icon of the late 18th century for her prominent role in fashion, politics and society in a predominately male dominated environment.[25][26] She was involved in promoting Charles James Fox (who died in the Bed Chamber of the Villa in 1806[27]) and his Whig party.[28] Raised from birth at Althorp House in Northampton and Spencer House in Green Park, she enjoyed spending time at Chiswick Villa which she referred to as her "earthly paradise".[26][29] Chiswick Villa became her refuge from a life of excess and self-indulgence. She regularly invited many members of the Whig party to the house for tea parties in the garden.[30][31] In 1788 the Cavendish family demolished the Jacobean house and hired architect John White to add two wings to the Villa to increase the amount of accommodation.[32] Georgiana was personally responsible for the building of the Classical Bridge in 1774, designed by the architect James Wyatt,[32] and the planting of roses on the walls of the new wings and the sides of the buildings.

19th century and decline

Georgina Cavendish died in 1806, but the house remained popular with the Whigs. In 1813, a 300 foot (91 m) conservatory was built by Samuel Ware, with the purpose of housing exotic fruits and camellias.[33] Gardener Lewis Kennedy built an Italian inspired geometric garden around the conservatory.

In 1827, after a rapid decline in health, Tory Prime Minister George Canning died in the same room where Charles James Fox had died in 1806.[34]

Between 1862 and 1892 the villa was rented by the Cavendish family to a number of successive tenants, including the Duchess of Sutherland in 1867,[35] the Prince of Wales in the 1870s,[36] and the Marquess of Bute, patron of the painter William Burgess, from 1881 to 1892.[37] From 1892, the 9th Duke of Devonshire rented the villa to Doctors T S and C M Tuke, and it was used by them as a mental hospital for wealthy male and female patients until 1928.[38] In 1897, the two sphinxes on the main gate were removed to Green Park during the celebrations of Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee. They were never returned.[39]

The 9th Duke of Devonshire subsequently sold Chiswick House to Middlesex County Council, the purchase price being met in part by contributions from public subscribers, including King George V .[38] The Villa became a fire station during World War II,[40] and suffered damage; vibration from the bombing of Chiswick brought down the plasterwork in the Upper Tribunal and on 8 September 1944 a V2 rocket damaged one of the two wings.[41] They were later removed in 1956.[32]

Modern times and heritage

In 1948 extensive lobbying from the newly created Georgian Group,[42] which recognised the Villa's unique architectural heritage and its invaluable contribution to European architectural history, prevented it from being destroyed. The house then came under the aegis of the Ministry of Works, the forerunner of English Heritage.[43] Today the house is owned by the Department of Culture, Media and Sport and maintained by English Heritage.[39]

Hounslow Council and English Heritage formed the Chiswick House and Gardens Trust in 2005 to unify the management of the Villa and Gardens. The Trust took over the administration for the Villa and Gardens on July 1, 2010 following the completion of the restoration works. [44] A Heritage Lottery Fund Grant was complemented by approximately GBP 4 million from other sources, for restoration of the gardens in 2007.[45] The garden is open to the public from dawn until dusk without charge.[46]

Notable guests

Although little is known of the people who stayed or visited Chiswick Villa in Lord Burlington's lifetime, many important visitors to the property are recorded as visiting throughout its history. These included leading figures of the European 'Enlightenment' including the philosophers François-Marie Arouet (Voltaire, 1694–1778) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778); the future US Presidents John Adams (1735–1826) and Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826); Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790); the German landscape artist Prince Hermann von Pückler-Muskau; the Italian statesman Giuseppe Garibaldi (1807–1882); Russian Tsars Nicholas I (1796–1855) and Alexander I (1777–1825); the king of Persia; Queen Victoria (1819–1901) and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg (1819–61); Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832); Prince Leopold III, Duke of Anhalt-Dessau (1740–1817); Prime Ministers William Ewart Gladstone (1809–1898) and Sir Robert Walpole (1676–1745); Queen Caroline of Brandenburg-Ansbach (1683–1737); John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute (1713–92) his architect William Burges (1827–1881) and the present Prince of Wales and Princess Margaret.[citation needed]

The Villa building

View of the Villa from the southwest, showing a Venetian window and an unusual use of chimneys disguised as obelisks

View of the Villa from the southwest, showing a Venetian window and an unusual use of chimneys disguised as obelisks

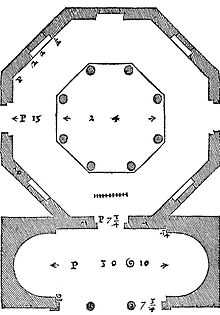

The architectural historian Richard Hewlings has established that Chiswick House was an attempt by Lord Burlington to create a Roman villa, rather than Renaissance pastiche, situated in a symbolic Roman garden.[47] Chiswick Villa is inspired in part by several buildings of the 16th-century Italian architects Andrea Palladio (1508–1580) and his assistant Vincenzo Scamozzi (1552–1616). The house is often said to be directly inspired by Palladio's Villa Capra "La Rotonda" near Vicenza,[48] due to the fact that architect Colen Campbell had offered Lord Burlington a design for a Villa very closely based on the Villa Capra for his use at Chiswick. However, although still clearly influential, Lord Burlington had rejected this design and it was subsequently used at Mereworth Castle, Kent.[49] Lord Burlington was not just restricted to the influence of Andrea Palladio as his library list at Chiswick indicates. He owned books by influential Italian Renaissance architects such as Sebastiano Serlio and Leon Battista Alberti and his library contained books by French architects,sculptors, illustrators and architectural theorists such as Jean Cotelle, Philibert de l'Orme, Abraham Bosse, Jean Bullant, Salomon de Caus, Roland Fréart de Chambray, Hugues Sambin, Antoine Desgodetz, and John James's translation of Claude Perrault's Treatise of the Five Orders. Whether Palladio's work inspired Chiswick or not, the Renaissance architect exerted an important influence on Lord Burlington through his plans and reconstructions of lost Roman buildings; many of these unpublished and little known, were purchased by Burlington on his second Grand Tour and housed in the Blue Velvet Room, which served as his study.[50] These reconstructions were the source for many of the varied geometric shapes within Burlington's Villa, including the use of the octagon, circle and rectangle (with apses).[51][52][53] Possibly the most influential building reconstructed by Palladio and used at Chiswick was the monumental Roman Baths of Diocletian:[53][54] references to this building can be found in the Domed Hall, Gallery, Library and Link rooms.

Burlington's use of Roman sources can be viewed in the steep-pitched dome of the villa which is derived from the Pantheon in Rome. However, the source for the octagonal form of the dome, the Upper Tribunal, Lower Tribunal and cellar at Chiswick all possibly derive from Vincenzo Scamozzi's Rocca Pisana near Vicenza.[5] Burlington may also have been influenced in his choice of octagon from the drawings of the Renaissance architect Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1554),[55] or from Roman buildings of antiquity (for example, Lord Burlington owned Andrea Palladio's drawings of the octagonal mausoleum at Diocletian's Palace at Split in modern Croatia).[56] Archaeological remains have shown the Roman willingness to experiment with different geometric forms in their buildings, such as the underground octagonal hall in Nero's Domus Aurea.

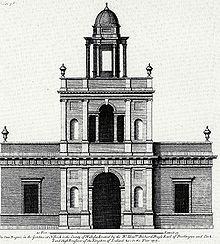

The brick-built Villa's facade is faced in Portland stone, with a small amount of stucco. The finely carved Corinthian capitals on the projecting six-column portico at Chiswick, carved by John Boson, are derived from Rome's Temple of Castor and Pollux.[57] The inset door, projecting plinth and 'v'-necked rusticated vermiculation (resembling tufa) were all derived from the base of Trajan's Column. The short sections of crenellated wall with ball finials which extend out either side of the villa were symbolic of medieval (or Roman) fortified town walls and were inspired by their use by Palladio at his church of San Giorgio Maggiore in Venice and by Inigo Jones (1573–1652) (Palladio also produced woodcuts of the Villa Foscari with crenellated sections of walls in his I Quattro Libri dell'Architettura in 1570, yet in reality they were never built). To reinforce this link two full-length statues of Palladio and Jones by the celebrated Flemish-born sculptor John Michael Rysbrack (1694–1770)[58] are positioned in front of these sections of wall. Palladio's influence can also be found in the general cubic form of the villa with its central hall with other rooms leading off its axis. The villa is a half cube of 70 feet (21 m) by 70 feet (21 m) by 35 feet.[citation needed] Inside are rooms of 10 feet (3.0 m) square, 15 feet (4.6 m) square and 15 feet (4.6 m) by 20 feet (6.1 m) by 25 feet.[citation needed] The distance from the apex of the dome to the base of the cellar is 70 feet (21 m), making the whole pile fit within a perfect, invisible cube. However, the decorative cornice at Chiswick was derived from a contemporary source, that of James Gibbs's cornice at the Church of St Martin-in-the-Fields, London.

On the portico leading to the Domed Hall is positioned a bust of the Roman Emperor Augustus. Augustus was regarded by many of the early 18th-century English aristocracy as the greatest of all the Roman Emperors (the early Georgian era was known as the Augustan Age). This link with the Emperor Augustus was reinforced in the garden at Chiswick through the presence of Egyptianizing objects such as sphinxes (who symbolically guard the 'Temple' front and rear), obelisks and stone lions. Lord Burlington and his contemporaries were conscious of the fact that it was Augustus who invaded Egypt and brought back Egyptian objects and erected them in Rome.[59]

Grand Tourists visiting Rome would have regarded such objects as Roman.[citation needed] Augustus was viewed through 18th-century eyes as a peacemaker who had brought to an end the civil wars. In his own words he "found Rome clay and left it marble".[citation needed] Augustus was also seen to have transformed Rome architecturally into a city fit to rule an expanding Empire, whilst carrying out large-scale public works (such as erecting drainage and aqueduct systems) for the benefit of the Roman people. The Roman architect Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (‘Vitruvius’) was also writing in the age of Augustus, a fact not lost on Lord Burlington.

The origins of Rome were made manifest at Chiswick through Burlington's strategic deployment of statues, including those of a Borghese gladiator, a Venus de' Medici, a wolf (used to inspire nostalgic memories of the legendary founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, a goat (symbolising the zodiac of Capricorn, the birth sign of the Emperor Augustus) and a boar located at the rear of the Villa (symbolic of the great Boar hunt). Inside the Villa many references to the Roman goddess Venus abound, as Venus was the mother of Aeneas who fled Troy and co-founded Rome. On the forecourt to the Villa are several 'term' statues that derive their forms from the Roman god Terminus, the god of distance and space. Such items therefore are used as boundary markers, positioned in the hedge at set distances apart.

At the rear of the Villa were positioned 'herm' statues that derive from the Greek god Hermes, the patron of travellers and thus are welcoming figures for all who wish to visit Lord Burlington's gardens (Lord Burlington's gardens at Chiswick were the most visited of all London villas.[citation needed] A small entrance charge applied).

Lord Burlington's intentions for his villa have never been established and received much speculation.[citation needed] The memoirist and gossip, John, Lord Hervey, for example, described the newly built Villa as 'Too small to live in, and too big to hang to a watch'. John Clerk of Penicuik described it as 'Rather curious than convenient', whilst Horace Walpole referred to the villa as 'the beautiful model'. Burlington only spoke of his villa in passing as his 'toy'. For the most part Burlington's intention for his new building remains a mystery.[60] What is certain is that the villa was never intended for occupation as it contained no kitchens and space for only three beds on the ground floor. It is possible that one purpose of the Villa was as an art gallery, as inventories show more than 167 paintings hanging in situ at Chiswick House in Lord Burlington's lifetime, many purchased on his two Grand Tours of Europe.

Relationship between Villa and Gardens

Lord Burlington's use of certain motifs and decorative schemes suggests that he regarded the Villa and its garden as a single entity. Features employed within the Villa are reflected in the garden.[citation needed] For example, the portico of the Villa displays a dado rail, with mock picture frames located above. The concept of a single entity of villa and garden is reinforced with the use of 'thermal' and 'serlian' windows within the Villa to capture natural light, and the positioning of the main staircase on the outside of the Villa. Within the interior of the Villa William Kent painted a plan of the Temple of Fortuna Virilis, the portico of which is reconstructed by Burlington on the Ionic Temple in the Orange Tree Garden. The apses utilised in the Gallery Rooms are likewise reproduced in the garden as terminating features to the two lakes. At the Bowling Green Lord Burlington positioned eight sweet chestnut trees around its perimeter, echoing the eight Tuscan columns located around the circumference of the Lower Tribune. To Burlington the primitive Tuscan order was associated with the use of trees as columns in ancient buildings. It is through such designs that Lord Burlington attempted to break down the barriers between man-made architecture and the architecture of nature.[citation needed] This philosophy was vaguely similar to Andrea Palladio's approach to his Villas in Vicenza, many of which had a semi-agricultural purpose, with the ground floor used for domestic and commercial activities, and the piano noble used for entertainment.

Principal rooms

Chiswick Villa is built of brick and its façade fronted with Portland stone with a small amount of stucco. The walls of the Villa, interrupted only by the porticos and Venetian windows, were deliberately austere, yet its interiors more refined and colourful.[61] This followed both Palladio and Jones's recommendations that the façade of a building, like that of a gentlemen, should be businesslike and serious, yet inside, away from prying eyes, could be more relaxed, playful and informal.

Two features of Chiswick Villa were revolutionary in English architectural practice- the centrally-planned layout, and the geometry of the rooms.[62] Chiswick Villa was the first domestic building in England to be designed with a central room which provided access to other rooms around its perimeter.[citation needed] The source for this feature was Andrea Palladio's centrally planned Villas, such as the Villa Capra and Villa Foscari. In the design of the rooms Lord Burlington used different geometric shapes, some with coved ceilings. Such a variety of differing spatial forms, many derived from Palladio's reconstructions of ancient Roman buildings (such as the Baths of Diocletian) had never previously been seen in English architecture. Many of the most important rooms within Chiswick Villa were situated on the piano nobile (Upper Floor) and comprise eight rooms and a link building.[citation needed] The rooms on this level were either of the Composite or Corinthian order of architecture to illustrate their important status.

In contrast, the Villa's ground-floor level was always intended to be plain and unadorned; it has low ceilings and little carving or gilding. Its rooms were for business, and Lord Burlington followed Palladio's recommendation to restrict the lowest order of Roman architecture, the Tuscan, to the ground floor. The three internal spiral staircases, based on Palladian precedent, were not intended to be accessed by Lord Burlington's guests, and were used only by the house servants; a dumb waiter was installed in place of the fourth internal staircase.

Upper Tribune (or Domed Hall)

The Upper Tribune is an octagonal room surmounted with a central dome. The dome has octagonal coffering of a type derived from the Basilica of Maxentius. The half-moon lunette windows below the dome are called 'Thermal' or 'Diocletian' windows. Their use at Chiswick was the first in northern Europe. Running beneath the Diocletian windows in the frieze are several lion heads, a feature also associated with the Diocletian bath houses, with Old St Paul's Cathedral under Inigo Jones, and with the Temple of Jerusalem.[citation needed]

In the original (and unexecuted) decorative scheme for this room, illustrated by William Kent around 1727, the spaces between the Diocletian windows were represented as half-moon panels with painted scenes, possibly frescos.[63] The picture frames were smaller than those in place today and therefore did not have the problem of resting uncomfortably just above the stone pediments. Instead of busts on brackets, Kent includes small panels placed between the four doors. Kent also illustrated small cherubs who reclined on the triangular pediments, similar to those illustrated by Inigo Jones on the new west front of Old St. Paul's Cathedral.

This room also contained four heavy gilded tables carved with Kent's characteristic baroque shells and accompanied with central carved lion masks (complementing the lion heads in the frieze). For each table two mahogany chairs were placed either side. These chairs had pediment backs which matched the four stone triangular pediments in this room. Eight large paintings were placed in gilded frames above the stone pediments and busts, including three of the Stuart and French Royal family, one executed by Sir Godfrey Kneller of Lord Burlington and his sisters, and popular mythological scenes such as "Daphne and Apollo" and "The Judgment of Paris" [64] Twelve antique busts of Roman and Greek figures, such as Emperors, poets, politicians and generals were also positioned on gilded brackets designed by Lord Burlington..

In the centre of the floor in this room is positioned an eight-pointed star, a potential reference to the star of the Order of the Garter which was introduced by King Charles I in 1629 and received by Lord Burlington from King George II in 1730.[65] However, positioned immediately before the large portrait of King Charles I and his family it provides further circumstantial evidence that Lord Burlington may have received an earlier secret Garter from the Stuart Kings in exile (in this painting King Charles I can be seen wearing the blue sash of the Garter with a "Lesser" George attached).

This central room, which provides access to the Gallery, Green and Red Velvet Rooms, would originally have been used for poetry readings, theatrical performances, gambling and small musical recitals (for example the composer George Frideric Handel (1685–1759) may have performed in this room. Handel lived with the family at Burlington House for two years when he arrived in England in 1712). The Upper Tribune was entered from the outside staircase in imitation of the staircases on many of Palladio's Villas in Vicenza.

Gallery

View of the central Gallery showing the apse derived from the ancient Roman Temple of Venus and Roma

The tripartite series of rooms overlooking the garden at the rear of the Villa are collectively known as the ‘Gallery Rooms’. The distinctive apses here are derived from the Temple of Venus and Roma,- the same source that Inigo Jones utilised when he refaced the west front of old St. Paul's Cathedral before its destruction in 1666.[citation needed] In the four niches were placed classical mythological statues of a Muse, Mercury, Apollo and Venus. This Gallery was designed as a statue Gallery and if in Italy this series of rooms would have been a loggia (a room open to the elements on one or more sides). The distinctive nine-panelled compartmentalised ceiling is a conflation of two ceilings derived from The Queen's House at Greenwich and The Banqueting House at Whitehall, both designed by Inigo Jones and both Royal apartments.

The central painting, by the Venetian artist Sebastiano Ricci (1659–1734), is a close copy of Paolo Veronese's (c.1528–88) ‘The Defense of Scutari’ located in the Doge's Palace, Venice.[66] The side paintings, believed to be by William Kent, depict double cornucopias which form crusader tents accompanied by Turkish prisoners with arms and armour positioned in various postures of captivity. The military theme in these paintings may possibly be a reference to Lord Burlington's status as a Knight of the Order of the Garter or his position as head of the 'Gentlemen Pensioners' (symbolic bodyguards to the King). Alternatively these paintings may be of a Masonic motivation[67] as in the 18th century it was believed that the Crusader Military orders, such as The Poor Knights of the Temple of Solomon (Knights Templar) and the Knights of St John (Hospitallers), were in some way inexplicably linked. These higher 'Chivalric and Historic' orders met in 'encampments' rather than lodges and were predominately Christian in their outlook and composition.

This room also contains two purple Egyptian porphyry urns purchased by Burlington on his first Grand Tour in 1714. These are accompanied by two heavy tables designed by Kent with their distinctive shells and featuring a mask of Neptune, accompanied by two water cherubs wearing pearls. The two handsome marble tops were inlaid with twenty two different types of marble and formed into geometric shapes with Greek Key (meander) borders. These were also joined by two torchers (flame holders) in the form of ‘Terms’. Either end of the Gallery are rooms that are circular and octagonal in shape. Together with the central rectangular Gallery, this series of geometric forms derive from Andrea Palladio's reconstructions of the Diocletian Bathhouses, which designs Lord Burlington owned. The female faces in the decorations of the two end rooms tell the story as told by Vitruvius of the origins of the Corinthian order.[68] The double sunflowers mark Lord and Lady Burlington's status as courtiers in the service of the King and Queen.

When the Villa was rented out to John Patrick Crichton-Stuart,3rd Marquess of Bute between 1865 and 1892, the central Gallery space, headed by apses at both ends, became his chapel.

Pillared Drawing Room

Today known as the Upper Link, this room was built in about to attach the new Villa to the old Jacobean House. The room is divided into three sections by the inclusion of unfluted Corinthian pillars which support an elaborate Corinthian entablature and ceiling. Above the entablature are open screens. These features are associated with the Baths of Diocletian and Caracalla, with Andrea Palladio's reconstructions again the source.[69] The ceiling is a copy of a 16th-century design depicting a decorative relief from a Roman sarcophagus from a room that may have sealed a mausoleum in the Roman funerary city of Pozzuoli. Outside this room is a central avenue flanked by funerary urns. This was Lord Burlington's attempt to symbolise the Appian Way which led to ancient Rome.[citation needed] It was by this road that the Emperor Augustus chose to enter Rome after the assassination of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC.

Green Velvet Room

The Green Velvet Room is 15 feet (4.6 m) by 20 feet (6.1 m) by 25 feet (7.6 m) in size and has a plaster ceiling with nine deeply recessed, gilded compartments derived from Inigo Jones's design for the Queen's Chapel at Old Somerset House (formally Denmark House, now demolished).[citation needed] Four depictions of the Green Man, pagan god of the oak and symbol of rebirth and resurrection, can be viewed carved into the marble fireplaces. The stone overmantels are a conflation of two designs by Inigo Jones and contain mythological paintings by Jean Baptiste Monnoyer (1636–99) and the Venetian painter Sebastiano Ricci who also carried out commissions at Burlington House in Piccadilly. This room later become an extension to Lady Burlington's Bedchamber and Closet, situated next door.[citation needed] Today this rooms contains six paintings of the gardens by the Flemish artist Pieter Andreas Rysbrack. These paintings are particularly valuable as they trace the development of the gardens from its formal to naturalistic appearance under Burlington, Kent and Pope. This room also features a painting by George Lambert with figures attributed to William Hogarth, regarded by art historians as the first painting to depict the English Landscape Garden.[citation needed]

Lady Burlington's Bedchamber and Closet

Lady Burlington died in this bedchamber in 1758, as did the Whig leader Charles James Fox in 1806.[70] The designation of this room in Lord Burlington's lifetime is unknown, but it appears Lady Burlington occupied this room some time after the death of her last daughter in 1754.[citation needed] Records at Chatsworth House show that the room was used intermittently as a children's nursery, undoubtedly for Lady Burlington's grand children and subsequently for the children of Georgiana and Elizabeth Foster. Today, several portraits of the Savile family can be viewed here and in the Bedchamber closet. One painting of note is of the poet Alexander Pope, painted by his good friend and fellow drinker William Kent.

The bedchamber closet is a perfect cube and has a ceiling design derived from the Queen's House, Greenwich. Originally the room would have contained around twenty seven paintings and access would have been restricted to Lady Burlington's closest friends.[citation needed] Prince of Wales swags and feathers can be seen in both rooms, possibly denoting the Villa as a Royal Palace.

Red Velvet Room

The Red Velvet Room once contained the largest and most expensive paintings in Lord Burlington's collection, including paintings by Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641), Giacomo Cavedone (1577–1660), Peter Paul Rubens (1573–1640), Rembrandt van Ryn (1606–69), Salvator Rosa (1615–1673), Pier Francesco Mola (1612–1666), Jacopo Ligozzi (c.1547–1632), Jean Lemaire (1598–1659), Francisque Millet (1642–79) and Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519).[71] The Venetian window in this room is derived from the Queen's Chapel at St James's Palace and was much imitated. The fireplaces and surrounds again come from sources by Inigo Jones, in this case from the Queen's House, Greenwich. These marble fireplaces have the inclusion of roses, Scottish thistles, grapes, sunflowers and fleur-de-lys which have been interpreted as Jacobite symbols.[72]

The ceiling, similar in design to that in the Green Velvet Room, but containing painted panels has at its centre a painting by William Kent representing Lord Burlington's patronage of the arts. The main character is the Roman god Mercury, the great patron of the arts and god of commerce, who is dispensing money into the arts depicted at the bottom of the panel. Burlington's wealth is represented by a putto who holds a cornucopia. The arts are represented by a self-portrait of William Kent (art), a supine bust of Inigo Jones (sculpture) and a putto with a temple plan of the Temple of Fortuna Virilis as depicted by Palladio.

An additional interpretation of this ceiling and its iconography relates to Freemasonry and its legendary history,[73] and that this space could have functioned as a Masonic Lodge. Positioned around the central painting are six roundels containing personifications of six of the then known planets of the Moon, Venus, Sun, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn with their associated zodiac signs. The seventh planet, Mercury, is personified in the central painting and is accompanied by a section of the northern zodiacal wheel containing the zodiacs for the planet Mercury and the constellations Gemini and Virgo. As such this ceiling painting is an important depiction of the universe as viewed through early Georgian eyes.[citation needed] (The Freemasons equated the seven known planets with the several liberal arts of which the fifth, Geometry, was considered the most important). At the centre of the painting is positioned the eight pointed star of the Order of the Garter which Lord Burlington received from King George II in 1730.[citation needed] This star also represents the Sun at the longest day of the year, the Summer Solstice, a day which the Freemasons associate with their Patron Saint, the 'messenger' (like Mercury) St John the Baptist.

A third, and potentially the most controversial explanation of the iconographical program of the central ceiling painting can be read in terms of Lord Burlington's suspected Jacobite loyalties.[citation needed] In this regard the meaning of the painting can be interpreted as the 'Crucifixion' and 'Resurrection' of King Charles I, the great Stuart martyr whose murder was promoted in Jacobite rhetoric as paralleled to the Passion of Jesus Christ (King Charles II returned from exile in 1660). If this reading is correct, the three ladies at the bottom of the central panel represent the three Maries who biblically were present at Christ's Crucifixion. Here the bare-breasted lady in blue with child is the Virgin Mary; the lady dressed in blue and red with reddish hair bound up in the style of a courtesan and on her knees as if at the base of the cross, Mary Magdalene. The third lady, holding a roundel containing the image of William Kent, is the remaining Mary. King Charles I is represented by Mercury, as the Stuarts associated themselves with this Roman god of eloquence (as depicted on the Banqueting House ceiling) and ruled as 'Mercurian' Monarchs. Lord Burlington would also have been aware of the Stuarts identification with Mercury through the theatre and masque set designs for the Stuart Court which were designed by Inigo Jones, the majority of which Lord Burlington owned.[citation needed]

Blue Velvet Room and Closet

The Blue Velvet Room is a perfect cube measuring 15 feet (4.6 m) square to the egg-and-dart lip.[citation needed] This room was Lord Burlington's studiola or ‘Drawing Room’ and originally contained a large table by William Kent which contained many designs by architects such as Andrea Palladio, Inigo Jones, John Webb and Vincenzo Scamozzi, which were ready for inspection. The ceiling is supported by eight large cyma reversa brackets, all in the Italian manner.[citation needed]

The coved ceiling, painted by William Kent, depicts a personification of ‘Architecture’ accompanied by three putti who grasp architectural implements in the form of T-Square, Set-Square and plumb line. ‘Architecture’ herself holds dividers and an unknown Temple plan (possible derived from the Jesuit architect Juan Bautista Villalpando who produced a classical reconstruction of the sanctum sanctorum at the heart of Solomon's Temple).[74] All four characters are seated on a fallen, hollow, metal column and are surrounded by a canopy of stars.

This ceiling represents Lord Burlington's interest in architecture. Alternatively the ceiling and its surrounding decoration (including the presence of rats and snakes) can be interpreted as having a Masonic motivation, as dividers, Set-Squares, T-Squares and plumb lines were important Masonic tools of morality. The putto to the left of ‘Architecture’ holds his finger to his lips suggesting silence or secrecy – a gesture mimicking the Egyptian child god of silence, Harpocrates. The idea that this room could have been used for initiation into Masonic mysteries is further supported by the proportions of this room as a perfect cube measuring 15x15x15 feet – the equivalent of 10 cubits by 10 cubits by 10 cubits, the stated dimensions of the Holy of Holies within Moses' Tabernacle according to the Bible.[citation needed]

Rooms on the ground floor

Lower Tribune

The Lower Tribune was essentially a waiting room (an ‘inner court’ or ‘vestibule’) for associates wishing to meet with Lord Burlington. The room is an octagon with eight Tuscan columns positioned around its perimeter. The architect Andrea Palladio made it clear that the Tuscan order of architecture, being the simplest of the five Roman orders, should only ever be used on the ground floor of a building as they were suitable for prisons, fortifications and amphitheatres.[citation needed] The eight pillars placed in a circular formation within on octagon are derived from the Baptistery of Constantine, (also known as the Baptistery of St John Lateran), a building reconstructed by Palladio in his I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura in 1570.

In this room today are twelve oil paintings of Chiswick House and gardens from the 1930s by Joseph William Topham Vinall. These paintings are of great interest as they show views that no longer exist with several showing the now lost interiors of the two Devonshire wing buildings.[citation needed]Library

Echoing the Gallery Rooms located above, the Library is a tripartite arrangement of rooms in octangular, rectangular and circular spatial forms. In the 1740s these rooms were lined with books in English, French, Italian and Latin. There were sections on architecture, antiques, sculpture, history, poetry, geography, fortification, science, divinity, philosophy and exploration. Three copies of the original 1570 publication of Andrea Palladio's I Quattro Libri dell’ Architettura were also placed here.[citation needed] Many of these books were housed in specially commissioned cabinets designed by William Kent. Today the Library is devoid of books, the collections having been removed to Chatsworth House, Derbyshire, or in the Royal Institute of British Architects library, which itself is now located in the Victoria and Albert Museum.[citation needed]

Twelve steps leading from the octagonal section of the Library descend to an octagonal brick cellar vaulted in Early English style. From this cellar wine and beer were raised by dumb waiter to guests on the piano nobile.

Lower Link

The Lower Link Building (Lower Pillared Drawing Room) was built around 1730 to link the Old Jacobean House to the new Villa. This room contained no fireplaces and its doors were open to the elements making this room very cold in the winter. In the four niches classical statues may have been positioned or flowers arranged in the summer. As according to Palladio's recommendations Burlington used two screens of Tuscan columns in this room with the arrangement replicating the tripartite arrangement of Roman Bath Houses. Today a lead Sphinx designed by the celebrated sculptor John Cheere is positioned on a plinth in this room, together with one of the famous Arundel Marbles which originally was inset into the base of an obelisk within the gardens and dates from the 3rd century BC.[citation needed]

Summer Parlour

The Summer Parlour was the most important room on the ground floor of the Villa. Possibly the oldest part of the complex, it was designed around 1715 by either Lord Burlington or James Gibbs, who also designed the ‘Pagan Temple’ in the gardens. James Gibbs was sacked by Lord Burlington on the advice of Colen Campbell.[75] Campbell subsequently took over Gibbs' architectural projects at Chiswick and Burlington House.

This is the only room on this level to have elevated and painted ceilings. Originally designed as a Summer Room for Lady Burlington, in terms of expense the contents of this private room doubled that of any other interior. The ceilings were executed by William Kent in the ‘Grotesque’ style- a mode of painting found predominately in subterranean Rome and popularised by the artist Raphael. This style, rare in Britain until reintroduced by William Kent at Kensington Palace, consisted of foliage forms interwoven with mythical creatures, such as cherubs or sphinxes.

In the ceiling of the Summer Parlour, Kent also added small owls, a motif that incorporated the owl of the Savile heraldic device. Kent designed two tables with matching mirror frames containing the owl device (the owl was also associated with the owl-faced Roman goddess Minerva, like Lady Burlington a great patroness of the arts). The original elbow chairs in this room were made by Stephen Langley and were unusual in their use of a Greek Key design interspersed with flowers.[citation needed] Today these large pieces of furniture are situated in the Green Velvet Room. At the rear of the Summer Parlour was a small china closet for Lady Burlington's most valuable objects. It was in the Summer Parlour that Lady Burlington was taught to paint by William Kent.

The central ceiling panel shows a sunflower at the centre, surrounded by four scenes of ports, each framed by shells, a reference to the Roman water goddess Venus and the Egyptian protector of ports and sailors, Isis. The panel nearest the fireplace (in Burlington's time the doorway) depicts two putti, one of whom sketches a female bust. The other holds his finger to his lips illustrating the need for silence.

The historian Jane Clark has noted that the female bust bears a resemblance to the Jacobite Queen and Polish Princess Maria Clementina Sobieska, wife of James the Old Pretender. The two putti with reddish hair who accompany her may be representations of the two Stuart Princes living in exile, Charles (Bonnie Prince Charlie- the 'Young Pretender') and Henry Stuart, who were children at the time the painting was executed.[citation needed] In the ceiling painting furthest away from the door the two putti reappear, this time hugging what appears to be a pug dog. The pug dog was a symbol adopted by the 'Society of the Mopses', a European pseudo-Masonic organisation of both male and female Freemasons.[76] As a symbol of revolt, the pug dog became particularly important after the publication of Pope Clement XII's Papal Bull In Eminenti in 1738 which condemned Catholic involvement in 'Craft' Freemasonry. As Clark explains, a symbolic initiation of female Freemasons involved the visiting of ports, a ritual which provides a possible link to the four scenes of ports on the ceiling panel. As such the sunflower at the centre would double as a Masonic Blazing Star, echoing the Garter Blazing stars at the centre of the Red Velvet Room ceiling and in the centre of the floor in the Upper Tribunal.

Gardens

The gardens at Chiswick were an attempt to symbolically recreate a garden of ancient Rome which were believed to have followed the form of the gardens of Greece.[77] The gardens, like the Villa, were inspired by the architecture of ancient Rome combined with the influence of contemporary poetry and theatre design.[citation needed]

The gardens at Chiswick were originally of a standard Jacobean design, but from the 1720s they were in a constant state of transition. Burlington and Kent experimented with new designs, incorporating such diverse elements as mock fortifications, a Ha-ha, classical fabriques, statues, groves, faux Egyptian objects, bowling greens, winding walks, cascades and water features.

Authors of antiquity, such as Horace and Pliny, were major influences on 18th century thinkers through their descriptions of their own gardens, with alleys shaded by trees, parterres, topiary, and fountains. The first architect of the gardens at Chiswick appears to have been the King's gardener, Charles Bridgeman (1690–1738), who was believed to have worked on the gardens with Lord Burlington around 1720,[78] and subsequently with William Kent, whom Lord Burlington had brought back with him on his return from his second Grand Tour in 1719. William Kent was also inspired by the landscape paintings of the French artists Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665) and Claude Lorrain (1600–1682). The poet Alexander Pope (who had his own Villa with gardens in nearby Twickenham), was also involved, and was responsible for confirming Lord Burlington's belief that Roman and Greek gardens were largely 'informal' affairs, with nature ruled by God.[citation needed]

Evidence for this belief was provided through his translation into English of Homer's cornerstones of European literature The Iliad and The Odyssey which provided brief glimpses of Greek gardens which gave validation to Burlington's belief in the naturalistic appearance of Roman gardens. Theatrical aspects were added to the gardens by William Kent, who studied the theatre and masque designs of Inigo Jones for the Stuart Court,[79] which were owned by Lord Burlington and housed within his Villa. Burlington, Kent and Pope were also informed by the writings of Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671–1713) who advocated 'variety' in a garden, but not complete deformalisation.

The gardens at Chiswick were filled with fabriques (garden buildings) which illustrated Lord Burlington's knowledge of Roman, Greek, Egyptian and Renaissance architecture, and statues and architecture which expressed his Whig (and very possibly Jacobite) ideals.

Lord Burlington's garden at Chiswick was one of the first to include garden buildings and ancient statues which were to symbolically evoke the mood and appearance of ancient Rome. Soon after other English gardens such as Stourhead, Stowe, West Wycombe, Holkham, and Rousham were to follow suit, creating a type of garden which eventually would become known internationally as the English Landscape Garden. Lord Burlington's gardens at Chiswick had a number of these fabriques including the Ionic Temple, Bagnio, Pagan Temple, Rustic House, and two Deer Houses.

Beyond the exedra in the gardens lies an area known as the 'Orange Tree Garden' in which was situated a small garden building known as the Ionic Temple. The Ionic Temple is circular in form and is derived from either the Pantheon in Rome or possibly from the Temple of Romulus. The portico of this temple is derived from the Temple of Portunus which William Kent illustrates in the ceiling of the Red Velvet Room within the Villa. Immediately in front of the Temple lies a circular pool of water with a small obelisk positioned in its centre. Around the base of the pool of water are three concentric rings of raised grass conforming originally to a 3:4:5 ratio echoing the dimensions of the Red and Green Velvet Room within the Villa. A second obelisk was erected at the centre of another patte d'oie or 'Goose Foot' beyond the cascade to west of the Villa.

A theater of hedges known as an exedra was designed by William Kent and originally displayed ancient statues of three unknown Roman gentlemen. However, these three statues were later speculatively 'identified' by the writer Daniel Defoe (1659–1731) as Caesar (100–44 BC) and Pompey (106–48 BC) responsible for the decline of the Roman republic facing a statue of Cicero (106–43 BC), the defender of the Republic. In 1733 Lord Burlington resigned his positions within the government and went into active opposition against Robert Walpole, Britain's first Prime Minister who was regarded as corrupting British politics and Whig values.[80] However, it was the figures of the poets Horace, Homer and Virgil, the philosopher Socrates, and the leaders Lucius Verus and Lycurgus which once graced the exedra whose political message was one of democracy and anti-tyranny.[81] (William Kent made a similar statement against Walpole for Lord Cobham at Stowe. The original design by William Kent for the end of the exedra was a stone 'Temple of Worthies' which was rejected by Lord Burlington and subsequently used by Lord Cobham at Stowe).

William Kent also added a cascade (a symbolic Grotto), inspired by the upper cascade of the gardens of the Villa Aldobrandini.[82] Kent's garden also featured a flower garden, an orchard, an aviary (which included an owl) and a symmetrical planned arrangement of trees known as the "Grove". To the side of the Grove was a patte d'oie, or 'Goosefoot', three avenues which terminated by buildings including the 'Bagnio' (or Casino, designed by Lord Burlington and Colen Campbell) in 1716, the 'Pagan Temple' (designed by the Catholic Baroque architect James Gibbs) and the Rustic House (designed by Lord Burlington).

Terminating one end of the Ha-ha stands a Deer House designed by Lord Burlington. A second Deer House once stood at the opposite end of the Ha-ha until replaced by Inigo Jones' gateway in 1738 (see below). Both Deer Houses featured pyramidal roofs and characteristic 'Virtuvian' doors; a feature that comes directly from Palladio's woodcuts from his I Quattro Libri dell' Architettura of 1570.[83] Immediately behind the Ha Ha and positioned between the two Deer Houses was a building known as the Orangery, which, as its name suggests, originally housed Lords Burlington's orange trees over the cold winter period (some of these trees were once positioned around the perimeter of the Ionic Temple). Part of the floor of this building was laid out in imitation of a Roman mosaic which English Heritage archaeologists in 2009 dated to the mid 18th century. Next to the remaining Deer Houses stands the Doric column on which was placed a statue of the Venus di' Medici.

In the 18th century statues of Venus were the most common statue in a garden as it was known that the goddess Venus was the protector of gardens and gardeners.[citation needed] The statue that can be seen on the Doric column today is a copy in Portland stone and was commissioned by the Chiswick House Friends in 2009. Other statues that Lord Burlington had made for the gardens included a wolf, a boar, a goat, a lion and lioness, a statue of the Roman god Mercury, a gladiator, Hercules, and Cain and Abel.

The lawn at the rear of the house was created by 1745 and planted with young Cedar of Lebanon trees which alternate with stone funerary urns designed by William Kent.[citation needed] Placed between the urns and the Cedar of Lebanon are three more sphinxes orientated to face the rising sun.

A lake was created around 1727 by widening the Bollo Brook.[citation needed] The excess soil was then heaped up behind William Kent's cascade to produce an elevated walkway for people to admire the gardens and a view of the nearby River Thames. A gateway designed by Inigo Jones in 1621 at Beaufort House in Chelsea (home of Sir Hans Sloane) was bought and removed by Lord Burlington and rebuilt in the gardens at Chiswick in 1738.[84]

It has also been claimed that Lord Burlington was influenced by Chinese gardens[85] which were largely informal, but the flavor of the Orient was not evoked in Burlington's gardens which were visually classically inspired. These gardens were universally Roman in its outlook.[86] Unlike Stowe, with its Temple of Worthies and busts such as the Black Prince, Queen Elizabeth I and Shakespeare, Burlington's gardens at Chiswick did not romance or mythologize England's illustrious past. This was possibly due to Burlington's intense dislike of the Gothic style which he regarded as barbaric and backward.[citation needed]

Lord Burlington's gardens at Chiswick were one of the most painted of English gardens in the 18th century. The painter Peter Andreas Rysbrack was commissioned to paint a series of eight paintings to record the transformation of the garden from formal Jacobean to informal picturesque at the end of the 1750s. Together with copies of a second set these paintings today hang in the Green Velvet Room. Other artists who were commissioned to record the appearance of the gardens were England's first landscape painter George Lambert (1700–1765), the French painter Jacques Rigaud (1681–1754) and the cartographer John Rocque (1709–1762) who produced an engraved survey of Chiswick in 1736 showing the Villa and many of its garden buildings.[citation needed]

Later developments (and demolitions) in the Gardens

In 1778, the decision was taken by the fifth Duke of Devonshire, on the advice of his gardener Samuel Lapidge, to make alterations to the gardens. These included the demolition of several of the garden buildings, including the Bagnio and Pagan Temple, both of which terminated the avenues of the patte d'oie and the filling in of two rectangular water basins to the side and rear of the Villa.[citation needed]

The Classic Bridge located beyond the Orange Tree Garden was built for Georgiana Spencer. It was constructed in 1774 to the designs of James Wyatt (1757–1806).[citation needed]

The Sixth Duke of Devonshire (the 'Bachelor' Duke) obtained permission in 1813 to relocate Burlington Road beyond the two piers at the front of the forecourt to its present position.

The gardens of Little Moreton Hall, an adjoining property to the east, were added in 1812, the Hall itself being demolished. In that same year the Italian Garden was laid out on the newly acquired grounds to a design by Lewis Kennedy. The Conservatory adjoining the Italian Garden was completed in 1813, and at 96m was the longest at that time. A collection of Camellias is housed in the Conservatory, some of which have survived from 1828 to this day.[citation needed] The garden designer Joseph Paxton (1803–1865), creator of the Crystal Palace, started his career in the gardens at Chiswick for the Royal Horticultural Society before his talents were recognised by William Cavendish, the sixth Duke of Devonshire and he relocated as ‘Head Gardener’ to Chatsworth House, Derbyshire.[citation needed]

See also

- Filming at Chiswick House

References

- ^ a b Furniture History Society (London; England) (1986). Furniture history. p. 84. http://books.google.com/books?id=xhuxAAAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Bryant, Julius; English Heritage (1993). London's country house collections. Scala Publications in association with English Heritage. p. 32. http://books.google.com/books?id=IJkzAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Rogers, Pat (2004). The Alexander Pope encyclopedia. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 61. ISBN 9780313324260. http://books.google.com/books?id=udRlsDhfhoUC&pg=PA61. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Baird, Rosemary (15 August 2007). Goodwood: Art and Architecture, Sport and Family. frances lincoln ltd. p. 19. ISBN 9780711227699. http://books.google.com/books?id=3TkOIfaghEgC&pg=PA19. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ a b Beltramini, Guido; Vicenza, Centro internazionale di studi di architettura "Andrea Palladio" di (15 October 1999). Palladio and Northern Europe: books, travellers, architects. Skira. ISBN 9788881185245. http://books.google.com/books?id=dSdQAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Beltramini, Guido; Burns, Howard (1 November 2008). Palladio. Royal Academy of Arts. ISBN 9781905711246. http://books.google.com/books?id=q4rrAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Wilton-Ely, John (1973). Apollo of the arts: Lord Burlington and his circle. Nottingham University Art Gallery. p. 31. http://books.google.com/books?id=xHDsAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Groves & Mawrey, p.68

- ^ Bryan, Julis (1993). London's Country House Collections. Kenwood, Chiswick, Marble Hill, Ranger's House. London: Scala Publications for English Heritage. p. 36.

- ^ Randhawa, Kiran (19 December 2007). "Chiswick House set for £12m facelift". London Evening Standard. http://www.thisislondon.co.uk/standard/article-23428558-chiswick-house-set-for-12m-facelift.do. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Rogers, Pat (2005). Pope and the destiny of the Stuarts: history, politics, and mythology in the age of Queen Anne. Oxford University Press. p. 126. ISBN 9780199274390. http://books.google.com/books?id=KgzLKMRiflwC&pg=PA126. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Groves & Mawrey, p.75

- ^ Fletcher, Sir Banister; Cruickshank, Dan (1996). Sir Banister Fletcher's a history of architecture. Architectural Press. p. 1046. ISBN 9780750622677. http://books.google.com/books?id=Gt1jTpXAThwC&pg=PA1046. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Sloan, Kim; Burnett, Andrew (2003). Enlightenment: discovering the world in the eighteenth century. British Museum Press. ISBN 9780714127651. http://books.google.com/books?id=QiYrAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ a b Barnard,, Toby and Clark, Jane (1995). Lord Burlington. Architecture, Art and Life. Hambledon Press. pp. 251–310.

- ^ a b Corp, Edward T. (1998). Lord Burlington: the man and his politics : questions of loyalty. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 9780773483675. http://books.google.com/books?id=uGswAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Edward Corp (ed.,)Lord Burlington. The Man and his Politics. Questions of Loyalty,(Lampeter: The Edwin Mellen Press, 1998, 2)

- ^ Ormrod, W. M. (July 2000). The lord lieutenants and high sheriffs of Yorkshire, 1066-2000. Wharncliffe Books. p. 29. http://books.google.com/books?id=OkSAAAAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Thomson, George Malcolm (April 1981). The prime ministers, from Robert Walpole to Margaret Thatcher. Morrow. p. 24. ISBN 9780688004323. http://books.google.com/books?id=tr11AAAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Journal of the Derbyshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. Derbyshire Archaeological Society. 1903. p. 130. http://books.google.com/books?id=W2IvAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Upper Wharfedale: Being a complete account of the history, antiquities and scenery of the picturesque valley of the Wharfe, from Otley to Langstrothdale. Elliot Stock. 1900. pp. 298–306. http://books.google.com/books?id=D8gvAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Murray, Venetia (1 March 1999). An elegant madness: high society in Regency England. Viking. p. 67. ISBN 9780670883288. http://books.google.com/books?id=ojGgAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ The art journal London. Virtue. 1870. p. 3. http://books.google.com/books?id=TI5CAAAAcAAJ&pg=PR3. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Lodge, Edmund (1867). The peerage and baronetage of the British Empire as at present existing. Hurst and Blackett. p. 179. http://books.google.com/books?id=RCoEAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA179. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Sharp Magazine October 2008. Contempo Media. p. 20. GGKEY:14CF21ZJ2WE. http://books.google.com/books?id=aT4OMhlVJf8C&pg=PA20. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ a b Gross, Jonathan David (July 2004). Emma, or, The unfortunate attachment: a sentimental novel. SUNY Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780791461464. http://books.google.com/books?id=s9itOPHgUIUC&pg=PR11. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Clarke, Benjamin (1852). The British gazetteer, political, commercial, ecclesiastical, and historical: showing the distances of each place from London and Derby--gentlemen's seats--populations ... &c. Illustrated by a full set of county maps, with all the railways accurately laid down .... Published (for the proprietors) by H. G. Collins. p. 651. http://books.google.com/books?id=p80HAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA651. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Foreman, Amanda (16 January 2001). Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. Random House Digital, Inc.. ISBN 9780375753831. http://books.google.com/books?id=Qp7J5fCax1cC. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Foreman, Amanda (2001). "Georgiana's World. The Illustrated Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire". Harper Collins. p. 182.

- ^ Choice: publication of the Association of College and Research Libraries, a division of the American Library Association. American Library Association.. 2000. http://books.google.com/books?id=4wkoAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Jullian, Philippe (1967). Edward and the Edwardians. Viking Press. http://books.google.com/books?id=MFEjAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ a b c Hibbert, Christopher; Weinreb, Ben (8 August 2008). The London encyclopaedia. Macmillan. p. 165. ISBN 9781405049245. http://books.google.com/books?id=wN_H-__MBpYC&pg=PA165. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Groves & Mawrey, p. 78

- ^ England (1840). The parliamentary gazetteer of England and Wales. 4 vols. bound in 12 pt. with suppl.. p. 442. http://books.google.com/books?id=GNcHAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA442. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Cockburn, J. S.; King, H. P. F.; McDonnell, K. G. T.; University of London. Institute of Historical Research (1995). A History of the county of Middlesex. Published for the Institute of Historical Research by Oxford University Press. p. 75. http://books.google.com/books?id=VP3uAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Country life. Country Life, Ltd.. 1979. http://books.google.com/books?id=ynZMAAAAYAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Hewlings, Richard (2009). Chiswick House and Gardens. English Heritage Guide book. pp. 52–53.

- ^ a b Weinreb, Ben; Hibbert, Christopher (20 October 1983). The London encyclopaedia. MacMillan. p. 154. ISBN 9780333325568. http://books.google.com/books?id=4IJnAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ a b "The Restoration of Chiswick House Gardens". London Garden Trust. http://www.londongardenstrust.org/features/chiswick2006.htm. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Fisher, Lois H. (March 1980). A literary gazetteer of England. McGraw-Hill. p. 141. http://books.google.com/books?id=jDmdIHzcI70C. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Richardson, John (4 September 2000). The annals of London: a year-by-year record of a thousand years of history. University of California Press. p. 349. ISBN 9780520227958. http://books.google.com/books?id=0wUCjfE6Lk4C&pg=PA349. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Norwich, John Julius (1 January 1993). Britain's heritage. Rainbow Books. ISBN 9781856980067. http://books.google.com/books?id=E9bP3aZxP_EC. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- ^ Jones, Nigel R. (2005). Architecture of England, Scotland, and Wales. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 77. ISBN 9780313318504. http://books.google.com/books?id=epsFOeV1mCMC&pg=PA77. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ "UNVEILING OF THE RESTORED CHISWICK HOUSE GARDENS". Chiswick House and Gardens Trust. http://www.chgt.org.uk/documents/CHISWICK%20HOUSE%20GARDENS%20RESTORATION%20PRESS%20PACK.pdf. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Groves & Mawrey, p. 79

- ^ "Visitor information". Chiswick House and Gardens Trust. http://www.chgt.org.uk/?PageID=17. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Richard Hewlings, Chiswick House and Gardens: Appearance and Meaning in Toby Barnard and Jane Clark (eds) Lord Burlington. Architecture, Art and Life (London, Hambledon Press, 1995), pages 1–149.

- ^ Yarwood, Doreen (1970). Robert Adam. Scribner. p. 104. http://books.google.com/books?id=WdtPAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Mowl, Tim (2000). Gentlemen & players: gardeners of the English landscape. Sutton. p. 113. http://books.google.com/books?id=QFY9AQAAIAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Umbach, Maiken (2000). Federalism and Enlightenment in Germany, 1740-1806. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 87. ISBN 9781852851774. http://books.google.com/books?id=EY_RC1RCuRIC&pg=PA87. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Ellen Judy; Reill, Peter Hanns (August 2004). Encyclopedia of the Enlightenment. Infobase Publishing. p. 444. ISBN 9780816053353. http://books.google.com/books?id=t1pQ4YG-TDIC&pg=PA444. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ The Architects' journal. The Architectural Press. 1990. http://books.google.com/books?id=hyNNAAAAYAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ a b Christopher (1996). Western furniture: 1350 to the present day in the Victoria and Albert Museum. Cross River Press, Victoria and Albert Museum. ISBN 9780789202529. http://books.google.com/books?id=PD5QAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ New statesman society. Statesman & Nation Pub. Co. Ltd.. 1995. p. 93. http://books.google.com/books?id=Qe2FAAAAIAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Laird, Mark (1999). The flowering of the landscape garden: English pleasure grounds, 1720-1800. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 215. ISBN 9780812234572. http://books.google.com/books?id=pCbC-QQx6iEC&pg=PA215. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Turner, Louis; Ash, John (1975). The golden hordes: international tourism and the pleasure periphery. Constable. p. 37. ISBN 9780094603103. http://books.google.com/books?id=u-grAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ Coleridge, Samuel Taylor (1845). Encyclopaedia Metropolitana: Difform- Falter. B. Fellowes. p. 397. http://books.google.com/books?id=9wlGAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA397. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ This attribution has been lately challenged by Richard Hewlings. See Richard Hewlings, The Statues of Inigo Jones and Palladio at Chiswick House in English Heritage Historical Review, Volume 2, 2007, 71–83.

- ^ James Stevens Curl, The Egyptian Revival. Ancient Egypt as the Inspiration for Design Motifs in the West (Abingdon, Routledge, 2005) 22–30.

- ^ Julius Bryant, Preserving the Mystery: a tercentennial restoration inside Chiswick House in Dana Arnold, Belov'd by Ev'ry Muse. Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington & 4th Earl of Cork (1694–1753), (The Georgian Group, London, 2004), 29–36.

- ^ Cinzia Sicca (1990). The Architecture of the Wall. Astylism in the architecture of Lord Burlington'. Architectural History, 33. p. 83.

- ^ The Periodical. Oxford University Press. 1960. p. 145. http://books.google.com/books?id=hLHfAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ John Harris, The Palladian Revival. Lord Burlington, His Villa and Garden at Chiswick Yale Press, 1995, p.149

- ^ Julius Bryant,London's Country House CollectionsLondon: Scala Publicaations Ltd, 1993, pp.39, 42.

- ^ The National Archives, Public Record Office, WORK 34/277

- ^ Jane Clark, 'Lord Burlington is Here' in Toby Barnard and Jane Clark (eds.,) Lord Burlington. Architecture, Art and Life, London: the Hambledon Press, 1995, p.300

- ^ Jane Clark, 'Lord Burlington is Here' in Toby Barnard and Jane Clark (eds.,)Lord Burlington. Architecture, Art and Life (London: The Hambledon Press, 1995), p.300

- ^ Richard Hewlings, 'Chiswick House and Gardens: Appearance and Meaning' in Toby Barnard and Jane Clark (eds.,) Lord Burlington. Architecture, Art and Life (London: The Hambledon Press, 1995), p.116

- ^ Dalzell, William Ronald (1962). Architecture: the indispensable art. M. Joseph. p. 172. http://books.google.com/books?id=_FVQAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ John Harris, The Palladian Revival. Lord Burlington, His Villa and Garden at Chiswick (London: Yale University Press, 1995) p.265.

- ^ Julius Bryant, London's Country House Collections (London: Scala Publications, 1993) p.36

- ^ Geoffrey B.Seddon, The Jacobites and their Drinking Glasses, (Suffolk: The Antique Collectors' Club,1995).

- ^ See Ricky Pound, The Master Mason Slain: The Hiramic Legend in the Red Velvet Room at Chiswick House in Richard Hewlings (eds.) English Heritage Historical Review (Bristol, 2009), 154–163 and Barry Martin, The 'G' Spot: an Explanation of its Function and Location within the context of Chiswick House and Grounds in Edward Corp (eds.), Lord Burlington. The Man and his Politics. Questions of Loyalty (Lampeter, Edwin Mellen Press, 1998),71–90.

- ^ Tessa Morrison, Juan Bautista Villalpando's "Ezechielem Explanationes. A Sixteenth-Century Architectural Text (Lampeter, 2009).

- ^ Howard E.Stutchbury, The Architecture of Colen Campbell, (Manchester:Manchester University Press, 1967), 23.

- ^ For the pug dog as a Masonic symbol and the Society of the Mopses, see James Stevens Curl, The Art and Architecture of Freemasonry, (London: Batsford Press, 1991), 76–77 and Robin Simon, Panels and Pugs. Reflections and Speculations, in Apollo, (June, 1991), 371–373

- ^ For the influence of Rome on early eighteenth century English gardens, see Philip Ayres, Classical Culture and the Idea of Rome in Eighteenth-Century England (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997). This book also contains a valuable Appendix on books on archaeology owned by Burlington, 168.

- ^ Peter Willis, Charles Bridgeman and the English Landscape Garden, (Newcastle upon Tyne: Elysium Press, 2002).

- ^ John Peacock, The Stage Designs of Inigo Jones, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995).

- ^ Richard Hewlings, 'Chiswick House and Gardens: Appearance and Meaning' in Toby Barnard and Jane Clark (eds.,) Lord Burlington. Architecture, Art and Life (London: The Hambledon Press, 1995), p.137

- ^ See Christine Gerrard, The Patriot Opposition to Walpole. Politics, Poetry, and National Myth, 1725–1742 (Oxford:Oxford University, 1994).

- ^ Kenneth Woodbridge, William Kent as Landscape Gardener. A Re-Appraisel, Apollo Magazine, 1974, 126–37.

- ^ Andrea Palladio, I Quattro Libri dell' Architettura, Book 4, Venice, 1570, 94.

- ^ John Harris and Gordon Higgott, Inigo Jones. Complete Architectural Drawings (London: Zwemmer, 1989) pp. 128-131.

- ^ Basil Gray, Lord Burlington and Father Ripa's Chinese engravings, in British Museum Quartely, XXII, February 1960, 40–43

- ^ See David Jacques, On the Supposed Chineseness of the English Landscape Garden in Garden History, (Volume 18, Number 2, Autumn 1990) 180–191 and Osvald Siren, China and Gardens of Europe of the Eighteenth Century (Washington: Dumbarton Oaks, 1990).

Bibliography

- Groves, Linden; Mawrey, Gillian (24 August 2010). The Gardens of English Heritage. frances lincoln ltd. pp. 68–79. ISBN 9780711227712. http://books.google.com/books?id=u5RUagDQwrIC&pg=PA79.

Further reading

- Ackerman, James S., The Villa. Form and Ideology of Country Houses, (London: Thames and Hudson, 1995)

- Arciszewska, Barbara, The Hanoverian Court and the Triumph of Palladio. The Palladian Revival in Hanover and England c.1700, (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Dig, 2002)

- Ayres, Plilip, Classical Culture and the Idea of Rome in Eighteenth-Century England, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- Badeslade, J, Gandon, James, Rocque, J, & Woolfe, John, Vitruvius Britannicus (second series), (New York: Dover Publications, 2008). Originally published between 1739 and 1771

- Campbell, Colin, Vitruvius Britannicus, (New York: Dover Publications, 2007). Originally published in 1715.

- Harris, John, The Palladian Revival: Lord Burlington, His Villa and Garden at Chiswick, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994)

- Hewlings, Richard, Chiswick House and Gardens, (English Heritage guide book, 1989)

- Knight, Caroline, London's Country Houses, (West Sussex: Phillimore & Co Ltd, 2009), 109–115

- Parissien, Steven, Palladian Style, (London: Phaidon Press, 1994)

- Rykwert, Joseph, The First Moderns. The Architects of the Eighteenth Century, (MIT Press,1983)

- Watkin, David, Classical Country Houses: From the Archives of Country Life, (London: Aurum Press, 2010)

- White, Roger, Chiswick House and Gardens, (English Heritage guide book, 2001)

- Wilson, Michael I, William Kent. Architect, Designer, Painter, Gardener, 1685–1748, (Hampshire: Routledge & Kegan Paul PLC, 1984)

- Wittkower, Rudolf, Palladio and English Palladianism, (Hampshire: Thames and Hudson, 1974)

The English Landscape Garden

- Batty, Mavis, Alexander Pope. The Poet and the Landscape, (London: Barn Elms Publishing, 1999, 26–41)

- Chambers, Douglas, D.C, The Planters of the English Landscape Gardner, (New Heaven: Yale University Press, 1993)

- Hunt, John Dixon, The Picturesque Garden in Europe, (London: Thames & Hudson, 2002)

- Hunt, John Dixon, Garden and Grove. The Italian Renaissance Garden in the English Imagination: 1600–1750, (London: Dent & Sons, 1986)

- Mowl, Tomothy, Gentlemen and Players. Gardeners of the English Landscape, (Alan Sutton, 2004)

- Richardson, Tim, The Arcadian Friends. Inventing the English Landscape Garden, (London: Bantam Press, 2007, 187–190)

- Strong, Roy, The Artist & the Garden, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000)

- Williamson, Tom, Polite Landscapes. Gardens and Society in Eighteenth-Century England, (Alan Sutton Publishing, 1995)

William Kent

- Harris, John, William Kent, 1685–1748. A Poet on Paper, (The Soane Gallery exhibition catalogue, 30 October-19 December 1998)

- Jourdain, Margaret, The Work of William Kent, London, Country Life, 1948

- Mowl, Timothy, William Kent. Architect, Designer, Opportunist, (London: Jonathan Cape, 2006)

- Wilson, Michael I, William Kent. Architect, Designer, Painter, Gardener, 1685–1748, (Hampshire: Routledge & Kegan Paul PLC,1984)

Inigo Jones

- Anderson, Christy, Inigo Jones and the Classical Tradition, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006)

- Chaney, Edward, Inigo Jones's 'Roman Sketchbook', 2 vols (London, The Roxburghe Club, 2006).

- Harris, John and Higgott, Gordon, Inigo Jones. Complete Architectural Drawings, (New York: Philip Wilson Publishers,1989)

- Leapman, Michael, Inigo. The Troubled Life of Inigo Jones, Architect of the English Renaissance, (London: Review Books, 2003), 353–55

Georgiana Spencer

- Chapman, Caroline, (with Dormer, Jane), Elizabeth & Georgiana. The Duke of Devonshire & his Two Duchesses, (London: John Murray, 2002)

- Calder-Marchall, Arthur, The Two Duchesses, (Devon: Readers Union, 1978)

- Foreman, Amanda, Georgiana. Duchess of Devonshire, (London: Harper Collins Publishers, 1998)

- Masters, Brian, Georgiana, (London: Allison & Busby Ltd, 1997)

Freemasonry in the 18th century

- Curl, James Stevens, The Art and Architecture of Freemasonry, (London: Batsford, 1991)

- Harrison, David, The Genesis of Freemasonry, (Surrey: Lewis Masonic, 2009)

- Jacob, Margaret C. The Radical Enlightenment. Pantheists, Freemasons and Republicans, (Louisiana: Cornerstone Books, 2006 reprint)

- Jacob, Margaret C. Living the Enligtenment. Freemasonry and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Europe, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991)

- Rosenau, Helen, Vision of the Temple. The Image of the Temple of Jerusalem in Judaism and Christianity, (London: Oresko Books Ltd, 1979)

- Soulier-Detis, Elizabeth, Guess at the Rest: Cracking the Hogarth Code, (Lutterworth Press, 2010)

- Stevenson, David, The Origins of Freemasonry. Scotland's Century, 1590–1710, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988)

Magazines, Articles and Periodicals

- Bryant, Julius, Chiswick House- the inside story. Policies and problems of restoration, in Apollo Magazine, CXXXVI, 1992, 17–22

- Cornforth, John, Chiswick House, London, in Country Life, February 16, 1995, 32–37

- Wilton-Ely, John, Lord Burlington and the Virtuoso Portrait, in Architectural History, Volume 27, Design and Practice in British Architecture: studies in Architectural History Presented to Howard Colvin, 1984, 376–381

- Fellows, David, This old house. Excavations at Chiswick House, in Current Archaeology, Number 223, October 2008, 20–29

- Hewlings, Richard, Palladio in England. Chiswick House, London, in Country Life, January 28, 2009, 46–51

- Hewlings, Richard, The Statues of Inigo Jones and Palladio at Chiswick House, in English Heritage Historical Review, Volume 2, 2007, 71–83

- Hewlings, Richard, The Link Room at Chiswick House. Lord Burlington as antiquarian, in Apollo Magazine, CXLI, 1995, 28–29

- Kingsbury, Pamela D., The Tradition of the Soffitto Veneziano in Lord Burlington's Suburban Villa in Chiswick, in Architectural History, Volume 44, 2001, 145–152

- Pfister, Harold Francis, Burlingtonian Architectural Theory in England and America, in Winterthur Portfolio, Volume 11, 1976, 123–151